To understand China and its future, look to its past, social historian says

Hong Kong professor David Faure believes looking beyond official accounts and studying Chinese society is increasingly essential in a fast-changing world

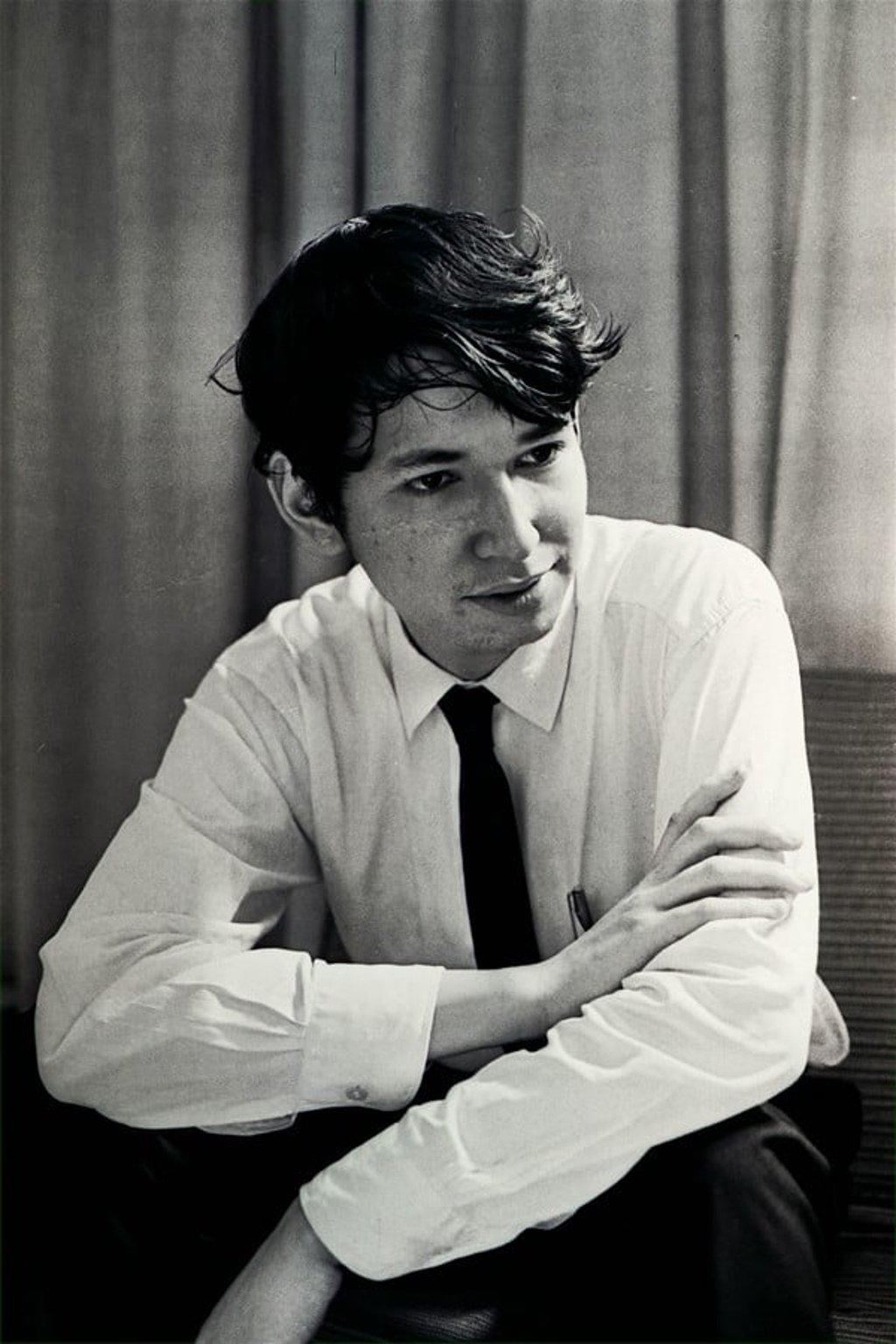

In a cluttered, slightly shambolic office overflowing with books and folders, at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Professor David Faure smiles benignly and reflects on what he considers his enormous good fortune.

“I was in the right place at the right time,” says the animated, jovial historian, as he reminisces on 30 years of exploring remote corners of China, to learn about its culture and history through the testimony of its people. “China was opening up in the 1980s and we were here in Hong Kong, so we were among the first generation who could run around the country and understand what Chinese society was really about.”

On-the-ground research was far from straightforward in the 80s. “China was a very different place,” Faure says. “It was not so easy to get around for all sorts of reasons, not least because a lot of the highways hadn’t been built. The bridges weren’t there. What takes you half an hour today took half a day back then. But the advantage was that before they built all those roads, the villages were more intact. The moment the highway system came, the countryside opened up.

“We all support economic prosperity, but it means a bygone age is not going to leave many signs. I saw the passing of that bygone age.”

A greater challenge for Faure and his colleagues was the race to record China’s history before so much of it was swept away by the waves of modernity that have transformed the country in the space of a generation. While China has been meticulous about its economic march, it has been rather less careful about preserving its past, and scores of the villages and neighbourhoods that Faure visited in the 80s and 90s would be unrecognisable today.

Now aged 70 and contemplating retirement, Faure, along with his colleagues – a core group of fewer than 20 scholars that includes four from Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, two from Guangzhou’s Sun Yat-sen University and one each from Peking University and Yale, in the United States – have recently completed an eight-year, HK$23.44 million research project, titled “The Historical Anthropology of Chinese Society”, working with other historians in Hong Kong and on the mainland.