Chinese artist Xu Bing’s Beijing retrospective reveals his attitudes to China and Western art, but don’t call him a pessimist

The UCCA exhibition ‘Thought and Method’ spans more than four decades of work in both China and the United States, and it quickly becomes clear that everything is not as it seems

Voices lower as viewers behold Xu Bing’s Book from the Sky (1988). Famous works of art are often greeted with a hushed reverence, but in this case, the sheer size of the piece also inspires awe. Vast, enclosed spaces that have the audacity to try to enclose the heavens command obeisance, and the aptly named Nave at Beijing’s Ullens Center for Contemporary Art (UCCA) is no exception. Xu’s work fills the space.

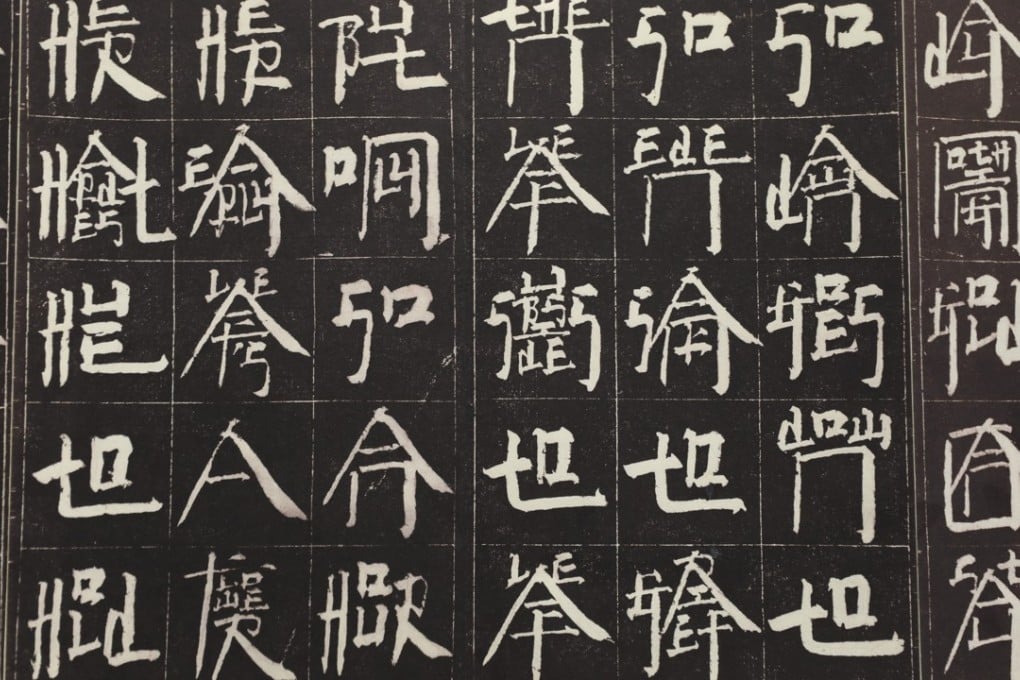

Tianshu, the Chinese title of the artwork, is a name given to a book of revelations penned by the gods, one which mere mortals lack the power to read. Unreadable, too, are the Book from the Sky’s scrolls, which are neatly covered in rows of woodcut characters. This pièce de résistance of the artist’s new retrospective is gobbledegook, with Xu having spent years devising 4,000 fake Chinese “words”, all the while determined to ensure that each at least looks like it could be the real thing. To understand the ambition of the undertaking, imagine that many English words, all hoaxes, but each one having the usual combination and balance of consonants and vowels, and never looking like a mistake.

We are all covered in what I call the tattoos of culture. Yet, words, images and culture as a whole fail us when all existing values and traditions are being challenged, and they cannot be used to explain what’s going on

Book from the Sky was first shown in Beijing, Xu’s hometown, exactly 30 years ago, at the height of China’s “85 New Wave” art movement. Avant-garde experimentation was exploding in the country as the trauma of the Cultural Revolution receded; China had unprecedented access to Western contemporary art, before the drawbridge went up again after the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown.

Back then, the Chinese art market was a mere whisper of the tyrannical force it is now. Borrowing from the Western conceptual paintbox of Dadaism, performance art and postmodernism, Chinese artists found new ways to ask fundamental questions about a world that, seen from their viewpoint, had always been dangerously capricious.

“My art has always been about the same things, even if the forms and materials are different,” says Xu, during an interview at the UCCA. “We are all covered in what I call the tattoos of culture. Yet, words, images and culture as a whole fail us when all existing values and traditions are being challenged, and they cannot be used to explain what’s going on.”

Artists all over the world are now witnessing major, confounding upheavals in their countries. Perhaps that is why we have seen more interest in how Chinese artists reacted in the past to their own.