Deadly Chinese-British gunboat clash off Hong Kong in 1953 still a matter for dispute

Seven sailors died when a Chinese gunboat attacked a Royal Navy launch 65 years ago. The latter’s commanding officer was blamed – but was he a useful scapegoat?

On September 9, an 85-year-old former British Royal Navy seaman will visit the colonial cemetery in Happy Valley, Hong Kong, as he does every year, to commemorate former shipmates killed in a bloody naval action off the coast of the then colony exactly 65 years ago.

The dramatic story of the attack on Her Majesty’s Motor Launch (HMML) 1323, of the Hong Kong Flotilla, by a Chinese communist gunboat on the Pearl River, which claimed the lives of seven of the 12 on board, made front-page headlines, provoked panic in diplomatic circles and led to an official Naval Board of Inquiry.

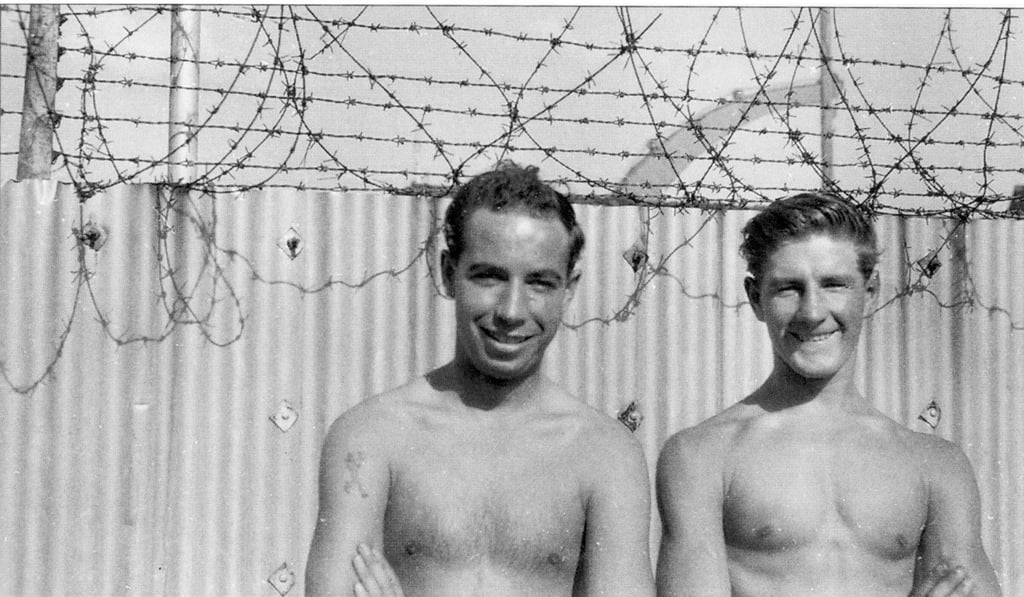

The 23-year-old commanding officer, Lieutenant Geoffrey Clement Xavier Merriman, who was from South Africa, had both legs severed above the knee and one hand smashed to tiny fragments by shell blasts. He bled to death in agony on the bridge. The surviving five crew members, led by leading seaman Gordon Cleaver, aged 20, and stoker mechanic Eric Milner, 22, extinguished fires, fitted emergency steering gear and navigated the severely damaged vessel back to the safety of Hong Kong, about 15 nautical miles away.

“Every year, I go to the graves in Happy Valley to pay my respects,” says John Fleming, who was serving in the Hong Kong Flotilla at the time. Were it not for a strange quirk of fate, he could have been among those killed. Fleming had served on HMML 1323 until he was transferred to another launch by his commanding officer, after a minor disciplinary incident, a few months before the fatal attack.

“That captain saved my life,” says Fleming, who knew all the victims personally and has written a book, Hong Kong: The Pearl River Incident, The Untold Story of HMML 1323 (2002), based on accounts of his former colleagues, his own observations of the mangled vessel and the findings of the subsequent inquiry.

Cleaver was awarded the British Empire Medal for his “outstanding coolness and courage”, and Milner and one other sailor, able seaman Ralph Shearman (posthumously), received official commendations for bravery, but their commanding officer was roundly condemned by the inquiry.