She took on the tobacco industry, and taught a city about sex: a Hong Kong doctor’s life

For 50 years, Dr Judith Mackay was one of Big Tobacco’s biggest enemies, and her battle to curb smoking had a major impact across the globe. She looks back on that and much else besides, including raising a family

Candyfloss and sandcastles I was born in Saltburn-by-the-Sea, in England’s North Yorkshire, in 1943. My childhood with my older sister, Margaret, was candyfloss and building sandcastles. My mother was one of the first women to go to university in Britain, in the early 1920s, and to vote, in 1928, but she suffered from deafness, so she was a homemaker and never worked for economic gain. My father, Ralph Patterson Longstaff, was commodore of the Ellerman Lines shipping company.

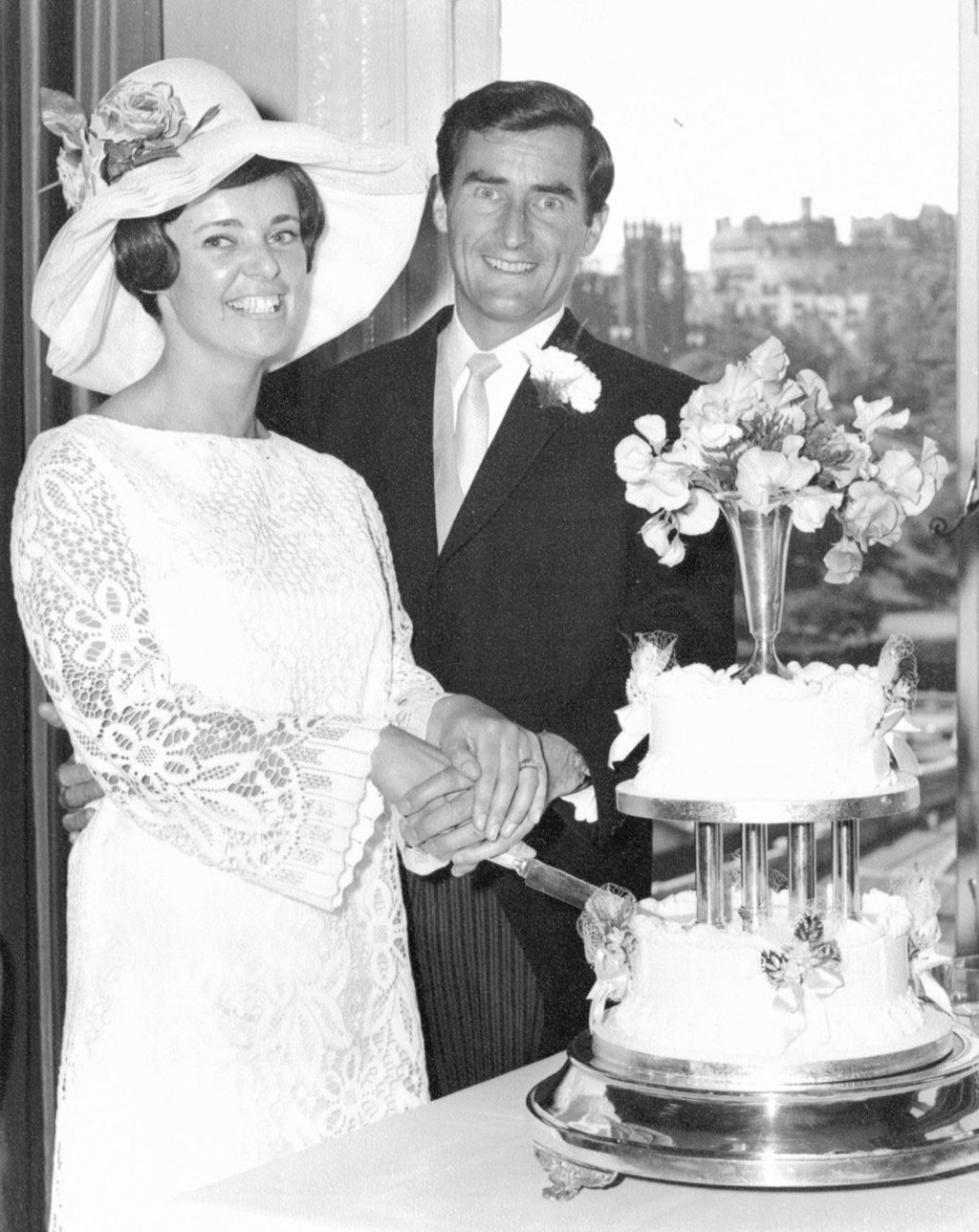

I went to the local grammar school, in Redcar. At the age of 24, after getting a degree in medicine from the University of Edinburgh two years earlier, I was doing my intern year in what was then City Hospital, in Edinburgh, when my future husband, John (Mackay), returned to do a postgraduate exam. We met in the TB (tuberculosis) ward. The second I saw John, I knew he was the man I was going to marry. John is a cautious Scot, so it took him a few weeks to get round to the same idea.

It was a turning point in my life in terms of outrage and becoming a feminist, because I was doing the same job as a male doctor was doing. It seemed so wrong. There was such a fuss about it that doctors got parity of pay first, followed by the rest of the civil service in the early 1970s.

Barefoot and illiterate Later, I worked at the University of Hong Kong paediatric unit, from 1970-73, and then in the medical unit, from 1973-76, while I obtained my postgraduate degree. For the research, we were looking at growth and development in Chinese children. The project was based at a Yau Ma Tei clinic.