America’s favourite pencil maker Dixon Ticonderoga blurs line of where it manufactures: in the US, Mexico or China?

The company Dixon Ticonderoga, now more than two centuries old, has received US government benefits even though it moved almost all of its production to Mexico and China

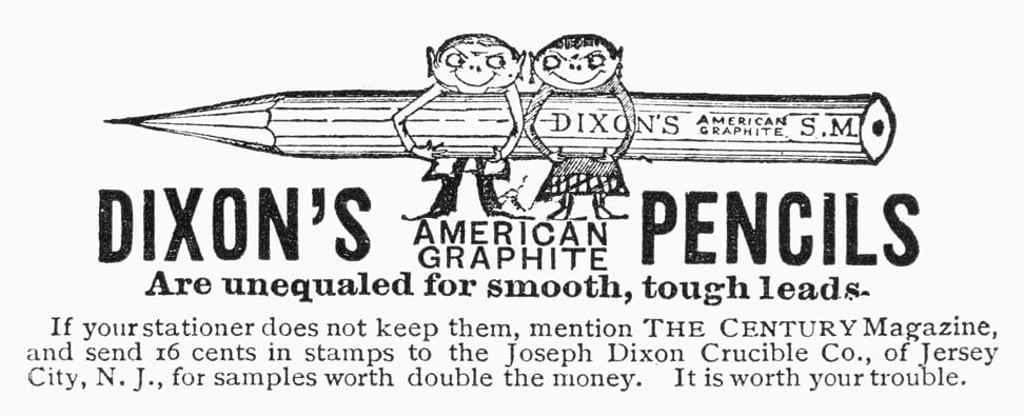

Office and art supplies company Dixon Ticonderoga sells millions of its iconic No. 2 yellow pencils to American children heading back to school every year. But the 223-year-old firm has survived by relying on more than just its reputation as the producer of sturdy and steady writing instruments. A key part of its approach has been to use United States trade law to reap government benefits and protection as it also moved almost all pencil production to Mexico and China.

The company has collected nearly US$5 million in federal funding aimed at victims of foreign trade abuse since 2005 and has requested millions more, according to US Customs and Border Protection records. And the fact that it has a distribution centre in the state of Georgia has allowed Dixon to successfully petition the US government to impose a 114.9 per cent duty, or tax, on Chinese competitors – more than doubling the costs for some other pencil manufacturers.

But even as it receives these protections, its status as an American firm is unclear. It has shed hundreds of jobs, and a key US agency removed Dixon’s designation as a “domestic” manufacturer because it made so few pencils at its Georgia plant.

Dixon, which was founded in New Jersey in 1795, was acquired by an Italian company in 2005, and it is unclear whether its US operation even has a chief executive.

“It’s kind of a secretive business,” says Mike Smith, president of Tennessee-based Musgrave Pencil, a competitor. “There’s not a whole lot of us left.”