Advertisement

Hong Kong’s Sha Tin Racecourse celebrates 40 years on international horse racing map

By attracting the world’s best horses, jockeys and trainers – and delivering all the necessary thrills and upsets – the New Territories racecourse cemented its position as a front runner on the international circuit

Reading Time:8 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

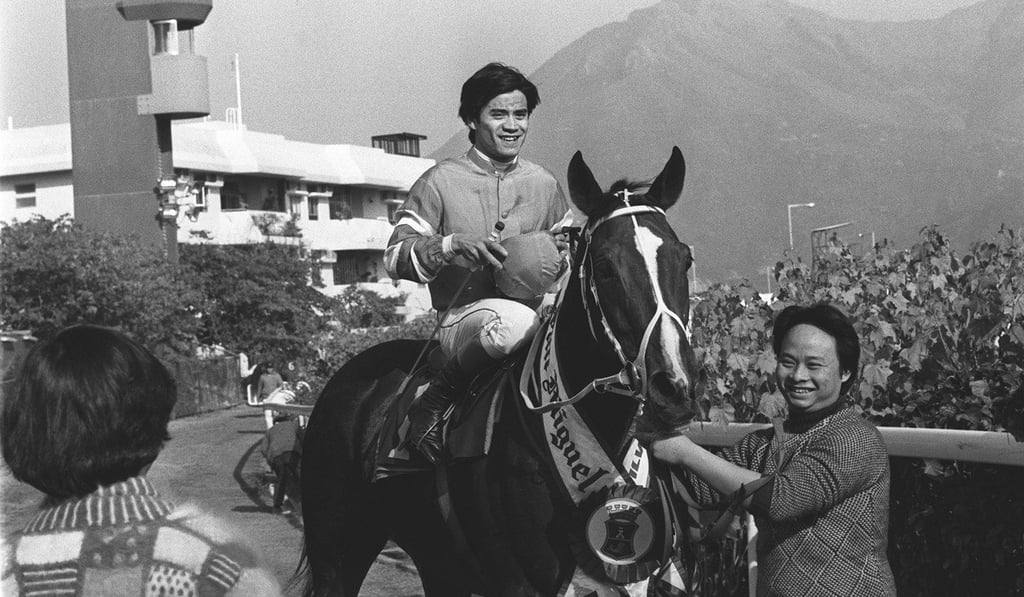

When Sha Tin Racecourse opened on October 7, 1978 – 40 years ago today and, aptly, in the Year of the Horse – it was praised for its sweeping track, its mountain scenery and the long stretch of the Shing Mun River which borders the back straight. For the city-dwelling punter, it offered rare space to breathe.

“Most people think Hong Kong is all skyscrapers, but out here we’re looking at mountains, and there’s fresh air. It’s home and I’m at ease,” says Hong Kong’s reigning champion jockey, Australian Zac Purton, who has been a resident of Sha Tin for 11 years.

Advertisement

Sha Tin Racecourse was opened five years before Purton, 35, was born, and for four decades has resounded to the thundering hooves of champions such as Co-Tack, River Verdon, Silent Witness and, more recently, Pakistan Star. Other famous names to have galloped around the outside of Penfold Park – the public area at the centre of the track – have included international race-winning Hong Kong horses Bullish Luck, Sacred Kingdom, Able Friend and Aerovelocity, with local fans seemingly just as happy to cheer on the runners-up as the winners.

With entry costing just HK$10, a day at the races does not come much cheaper than at Sha Tin, and before every meeting, the crowds are funnelled from the Racecourse MTR station to emerge Fblinking into the green expanse, white residential towers in the distance giving the scene a uniquely Hong Kong stamp.

Advertisement

All of the city’s racehorses were stabled, exercised and trained at Sha Tin until August, when a new training centre opened in the mainland to provide Hong Kong racing with extra capacity and facilities. Those racing at Happy Valley, Hong Kong’s original racecourse, are sent out on race day and returned the same evening. Jockeys, trainers, mafoos and key members of staff are housed within the New Territories complex.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x