Genital mutilation, sexual assault, gender pay gap: the reality of women’s lives globally

- Data offers harsh truths on everything from female genital mutilation and sexual assault to curtailed education opportunities.

- Case studies suggest that while widowhood brings challenges, many women are happiest once their partners have died.

The story of women is often told through numbers. Reports and studies tell us how much less money women make than men, how much more unusual it is for girls to go to school than for boys, or how much less likely women are to hold elected office or run companies than men.

Those analyses are important, but they can sometimes obscure the deeper truths of women’s experience.

We know 62 million girls are not in school. Why is that the case, and how can we do better? We are told one in five women will be sexually assaulted in her lifetime. How accurate are those numbers, and what can they really tell us about safety? We have heard women outlive men, often by a decade or more. What does life look like after a partner dies?

Here are some of the stories behind those numbers.

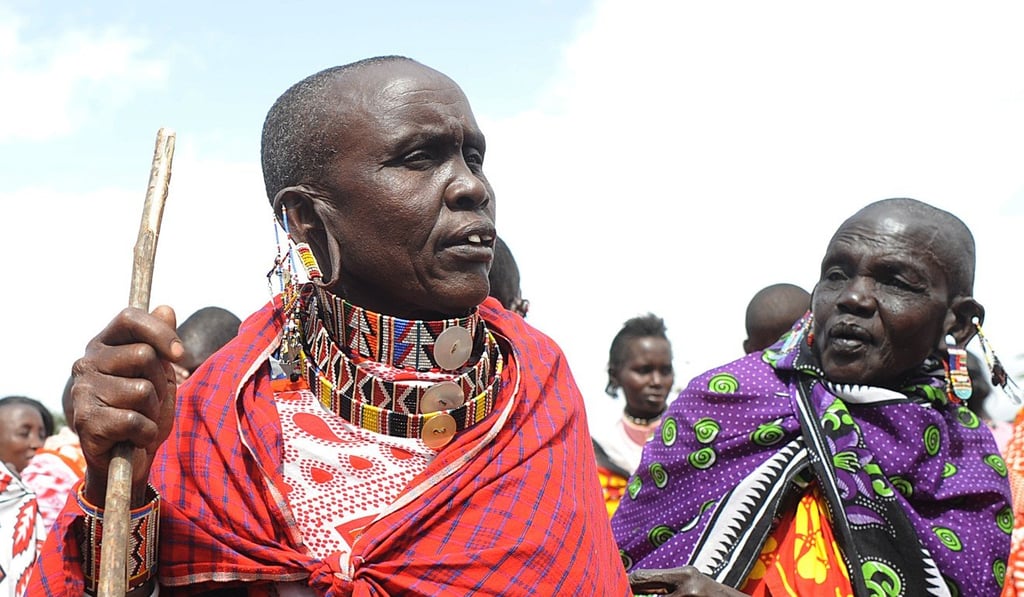

Bans – and growing disapproval – are not stopping female genital mutilation

The World Health Organization defines FGM as any procedure that involves the “partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons”. Despite having no medical benefits, the practice has been inflicted upon at least 200 million women and girls.