How Chinese bandits’ kidnapping of a blond British bride and her pet dogs became a global news story

- The abduction of Muriel ‘Tinko’ Pawley became headline news around the world, but the men captured with her barely rated a mention

- During her 41-day ordeal the 19-year-old suffered ‘beastly boredom’, threatened to haunt her captors and demanded lipstick

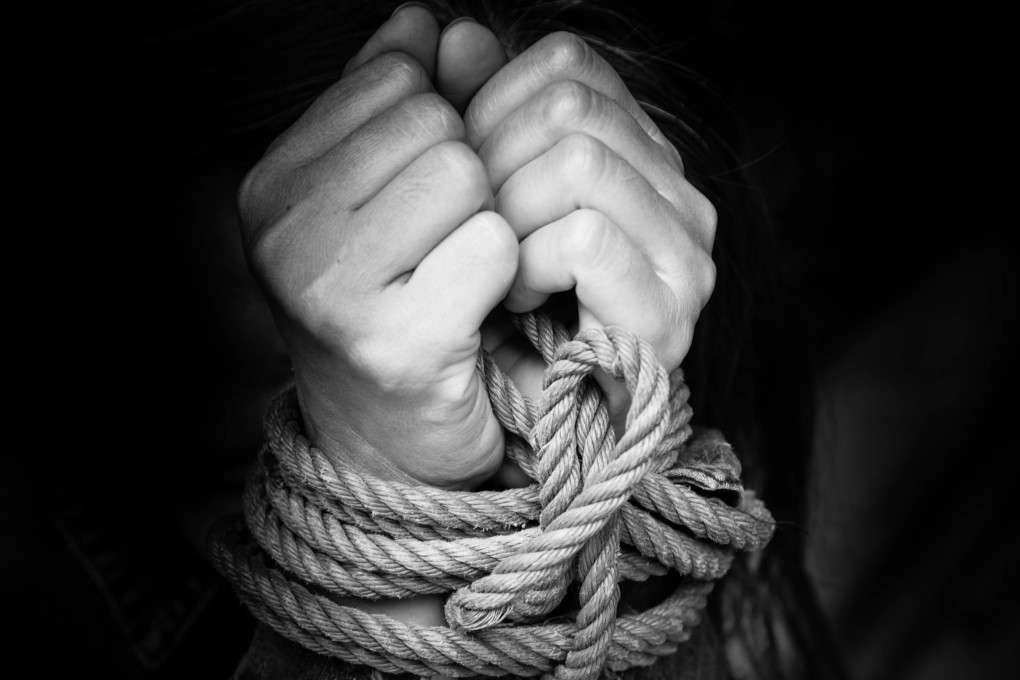

As temperatures began to drop and the winter of 1932 approached, the world was obsessed with just one news story – the kidnapping in northern China of 19-year-old Muriel “Tinko” Pawley and her dogs: German shepherds, Whisky and Rolf, and a pointer pup called Squiffy. When news reached London that Chinese bandits had threatened to cut off Pawley’s ears if a phenomenal ransom was not paid, there was an outcry from concerned newspaper readers in China’s treaty ports, Hong Kong, Europe, North America and Australia. “Tinko” Pawley was suddenly a household name and great copy.

Then at the height of his fame, having recently published his acclaimed novel Black Mischief, Evelyn Waugh could think of nothing else. He could not get the image of poor young Tinko out of his head – suffering in the Manchurian cold, starving, filthy, verminous, her dogs distraught. He bought every newspaper, scouring them for information on Tinko’s fate. He was far from alone. Theatre critic James Agate recorded the unfolding events of Tinko’s ordeal in captivity in his diary. Waugh eventually wrote a short story based on the kidnapping.

However, in the 1920s and ’30s, foreigners were being kidnapped with disturbing regularity in northern China – missionary families, salesmen roaming the interior in motor cars, hoping to make a deal or two, whole carriages of train passengers, entire steamships. It was an epidemic, ears sliced off and sent to families slow in paying, and it often ended in tragedy.

Warlord gangs, secret societies, pirates, bandits … it seemed kidnapping a foreigner was, between the wars, an integral component of the north Chinese economy. Most of these kidnappings received a few columns in the China coast and Hong Kong newspapers; a line or two in the newspapers overseas, if the victim was white. But Tinko made the papers every day, her every missive from captivity reprinted, every effort to rescue her detailed.

What was it that made Tinko Pawley’s kidnapping such a cause célèbre in late 1932?

Reuters breathlessly described Pawley as, “a charming blonde of eighteen summers”