The last king of Xinjiang: how Bertram Sheldrake went from condiment heir to Muslim monarch

- Bertram Sheldrake converted to Islam at the age of 15 and spent much of his fortune promoting the religion in Britain

- His efforts brought him an invitation from leaders of the newly proclaimed Muslim nation of Islamestan in China’s far west

It’s a long way from the south London suburb of Forest Hill to the once dreamed of Republic of Islamestan.

You may never have heard of Islamestan, in Chinese Turkestan, or its one-time “king”, Bertram Sheldrake. Islamestan is long gone, swallowed up in the historical shifts of a turbulent region, but for a brief and unlikely moment, an English pickle-factory heir ruled, with his wife, Sybil, over the newly independent Muslim country, to the far west of China.

The whole of what was then referred to as Chinese Turkestan, or Sinkiang (now Xinjiang), was, in the 1930s, subject to tribal rebellions and warlord uprisings. It was ultimately concluded by the chiefs of various tribes in the region that only an outsider (but necessarily a Muslim one) could bring unity to the region. Having read newspapers brought by travellers, they sent a delegation to south London to visit an Englishman who had caught their attention. Sheldrake was invited to assume the throne of Islamestan. Not being quite sure of the correct title for the new ruler, the British press helpfully offered some suggestions – “The Pickle King of Tartary”, “The English Emir of Kashgar”, “Lord of the Rooftop of the World”.

To contemporary British newspaper readers, it must have seemed as if Rudyard Kipling’s The Man Who Would Be King (1888), wherein two English adventurers, Dravot and Carnehan, become the leaders of Kafiristan, a remote region of Afghanistan, had come true. Having had a good public-school education on his father’s pickle profits, Sheldrake would have known Kipling’s cautionary tale. Things hadn’t turned out well for Dravot and Carnehan in Kafiristan; neither would they go smoothly in Islamestan for “The Pickle King of Tartary”.

Bertram William Sheldrake was born in the same year that Kipling’s cautionary tale was published, the son of Gosling Mullander Sheldrake (known simply as “George”), who ran the successful firm of G. Sheldrake, Manufacturers of Pickles, Sauces, Chutney, Ketchup, Vinegar, etc.; Bottlers of Capers, Curries, and other Condiments, located at 293-295 Albany Road, London, SE5. The business had done well since being founded in the 1870s, changing its name to the rather pedestrian South London Jam and Pickle Manufactory and then Sheldrake’s Pickles while trading up from the insalubrious surroundings of Southwark to the leafier environs of Denmark Hill.

Bertram must have been a precocious schoolboy. Although raised Catholic, in 1903, at the age of 15, he converted to Islam (then generally termed “Mohammedanism”), learned Arabic and changed his name to Khalid.

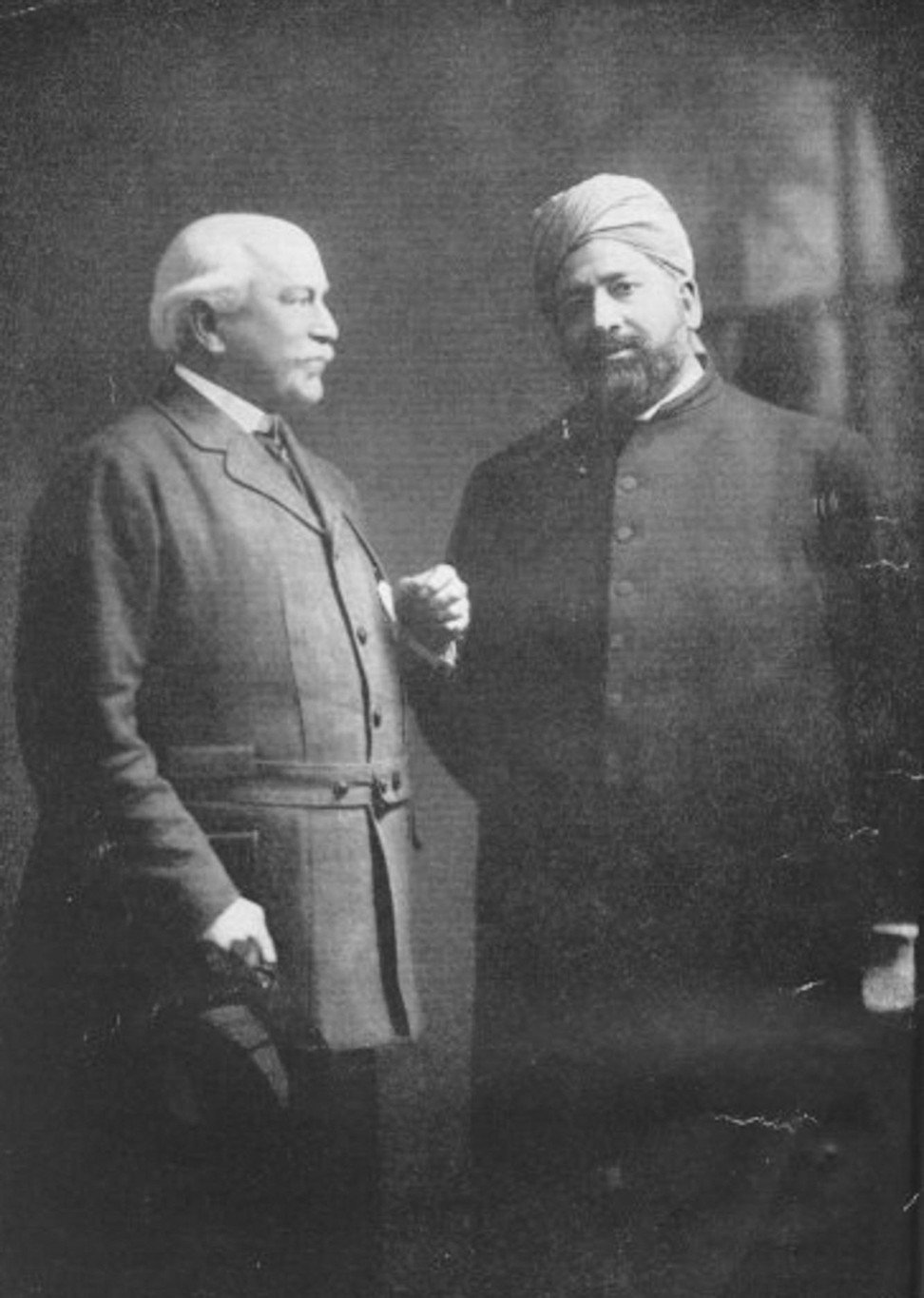

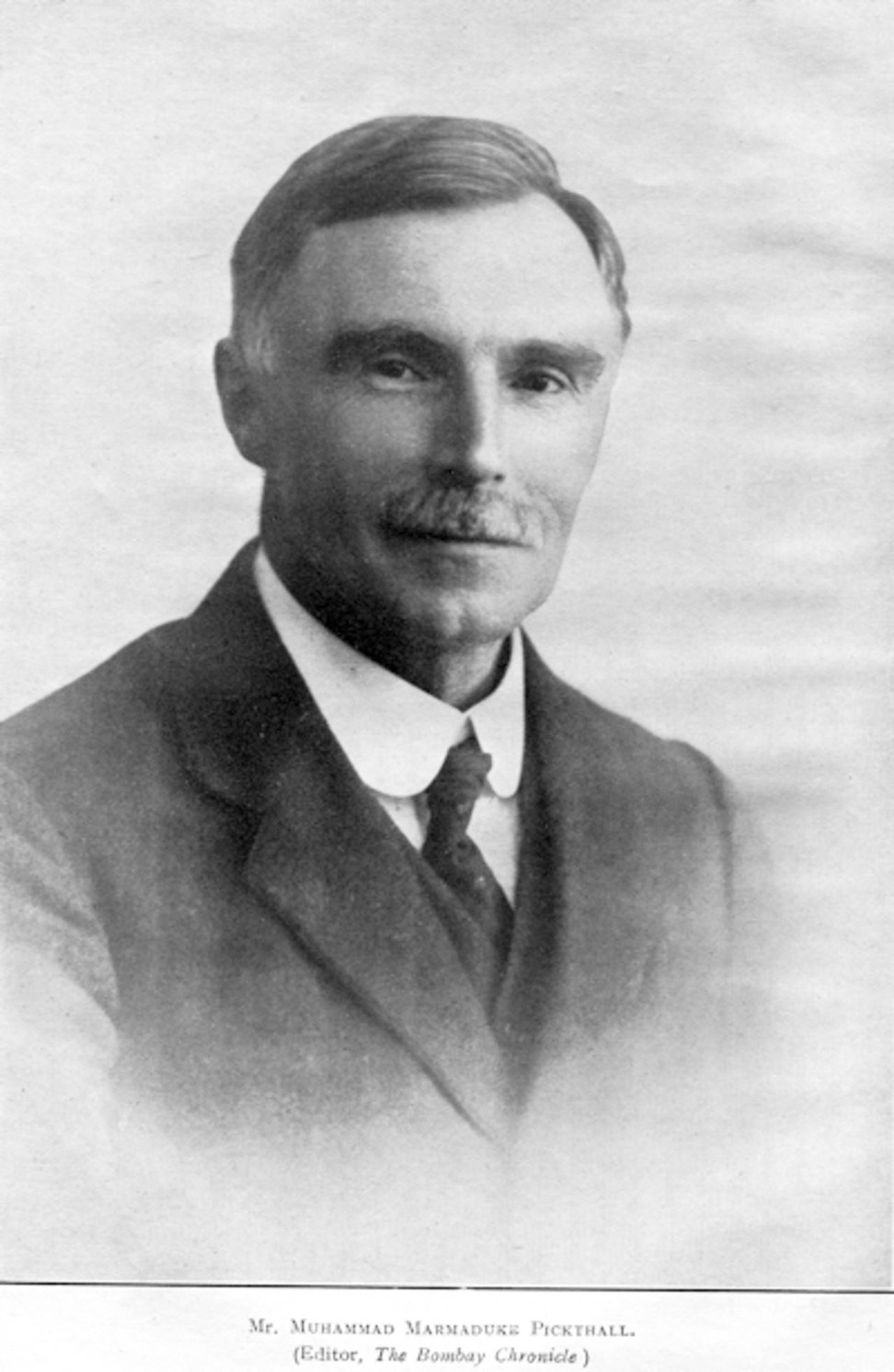

Sheldrake was a relatively early convert. A decade later, the first Muslim missionary to Britain, the Indian Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din, would make several high-profile conversions among socially connected and wealthy British people. These included Irish peer Lord Headley, who became known as Shaikh Rahmatullah al-Farooq, or more commonly in the newspapers as “The Moslem Peer”, and the scholar and novelist Marmaduke Pickthall, who became, more prosaically, Muhammad Marmaduke Pickthall. In 1930, Pickthall was to publish the most complete English translation of the Koran to date.

British people converted for various reasons. For Headley and Pickthall, it seems to have been because of an aesthetic appreciation of the Middle East and “Arabia”. Similarly so for the Scottish noblewoman and Mayfair socialite Lady Evelyn Murray, who had grown up in Cairo and Algiers. She converted and became Zainab Cobbold, undertaking the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia, several times. She was buried on her estate in the Scottish Highlands facing Mecca.

For others, such as Charles Hamilton, who converted in 1924, it was part of a wider search for order. Hamilton became Sir Abdullah Charles Edward Archibald Watkin Hamilton. A staunch Conservative, he would, in the 1930s, change tack and join Oswald Mosley’s far-right British Union of Fascists.

Less extreme was well-known Liverpool solicitor and temperance advocate William Quilliam, who converted after visiting Morocco. Having changed his name to Abdullah Quilliam, he used a donation from Nasrullah Khan, the crown prince of Afghanistan, to buy three terraced houses, establishing the Liverpool Muslim Institute in one of them.

The success of Sheldrake’s Pickles meant young Khalid didn’t need to work full-time for the family firm. He devoted his spare hours to Muslim causes, helping to found the journal Britain and India in 1920, launching the Muslim News Journal and serving as editor of The Minaret, an Islamic monthly based in London. He wrote frequently and sometimes provocatively. An article by Sheldrake in The Minaret in September 1927 suggesting Napoleon had flirted with conversion to Islam caused a stir on both sides of the English Channel.

Dr Khalid Sheldrake, as he was now referred to in the newspapers (having been awarded an honorary Ecuadorean doctorate of literature), found a wife, Sybil, who also converted, becoming Mrs Ghazia Sheldrake. They had two sons, who they raised in the Muslim faith. The family set up home in a detached house on quiet Gaynesford Road, in Forest Hill. It had a decent-sized front drive, a well-tended rear garden and was only a short commute from the Denmark Hill pickle factory.

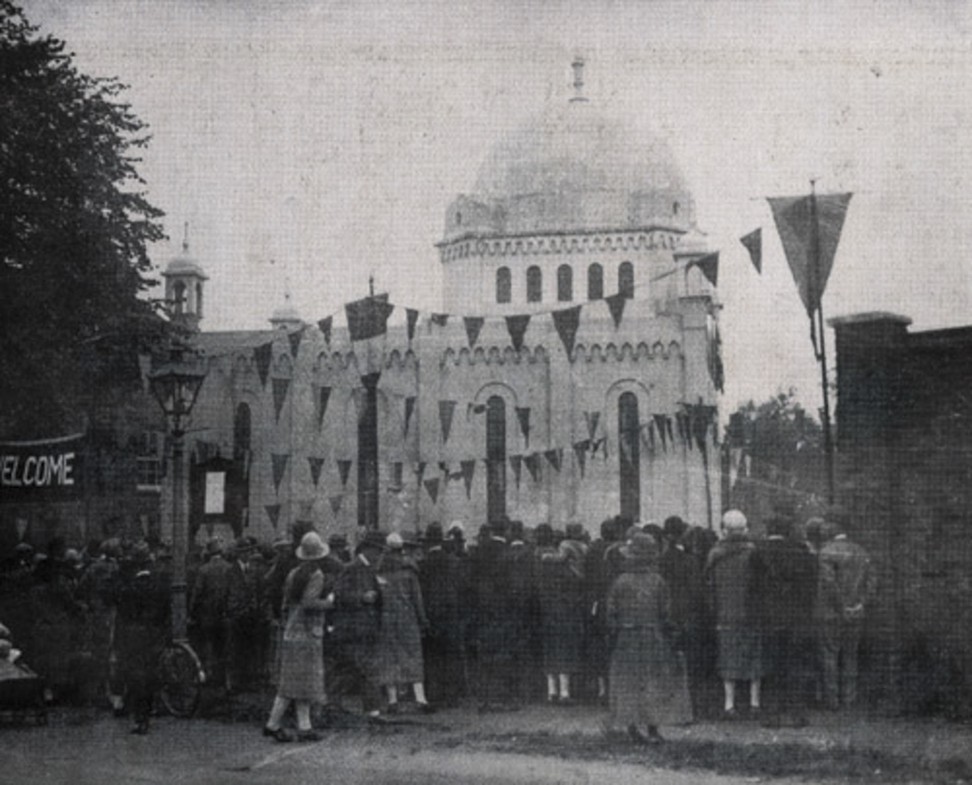

Sheldrake worked hard and committed his resources to opening mosques in Britain. He was involved with the financing and construction of London’s first purpose-built mosque, in Wandsworth, in 1926 (previously, London’s Muslims had gathered in private houses). He organised another mosque in Peckham Rye, in the converted basement of a house he donated.

Here, Sheldrake presided over his own group of activists and missionaries, the Western Islamic Association, which sought to spread the word of the Prophet among the Christian English. In 1927, it was reported that he had opened a mosque in East Dulwich, known as the Masjid-el-Dulwich, after raising funds through “Oriental Bazaars”.

Sheldrake also paid for the funerals of Muslims who had died in Britain. In 1928, his self-financed Indigent Muslims’ Burial Fund bankrolled the funeral of Sayed Ali, the long-standing elephant trainer at London Zoo.

Fleet Street was confused by Sheldrake. He was referred to as the “Sheik of all British Moslems” (which isn’t and wasn’t an official position) and often a picture of an unknown Muslim, portly, dark-skinned and in traditional clothing, was featured and identified as “Khalid Sheldrake”.

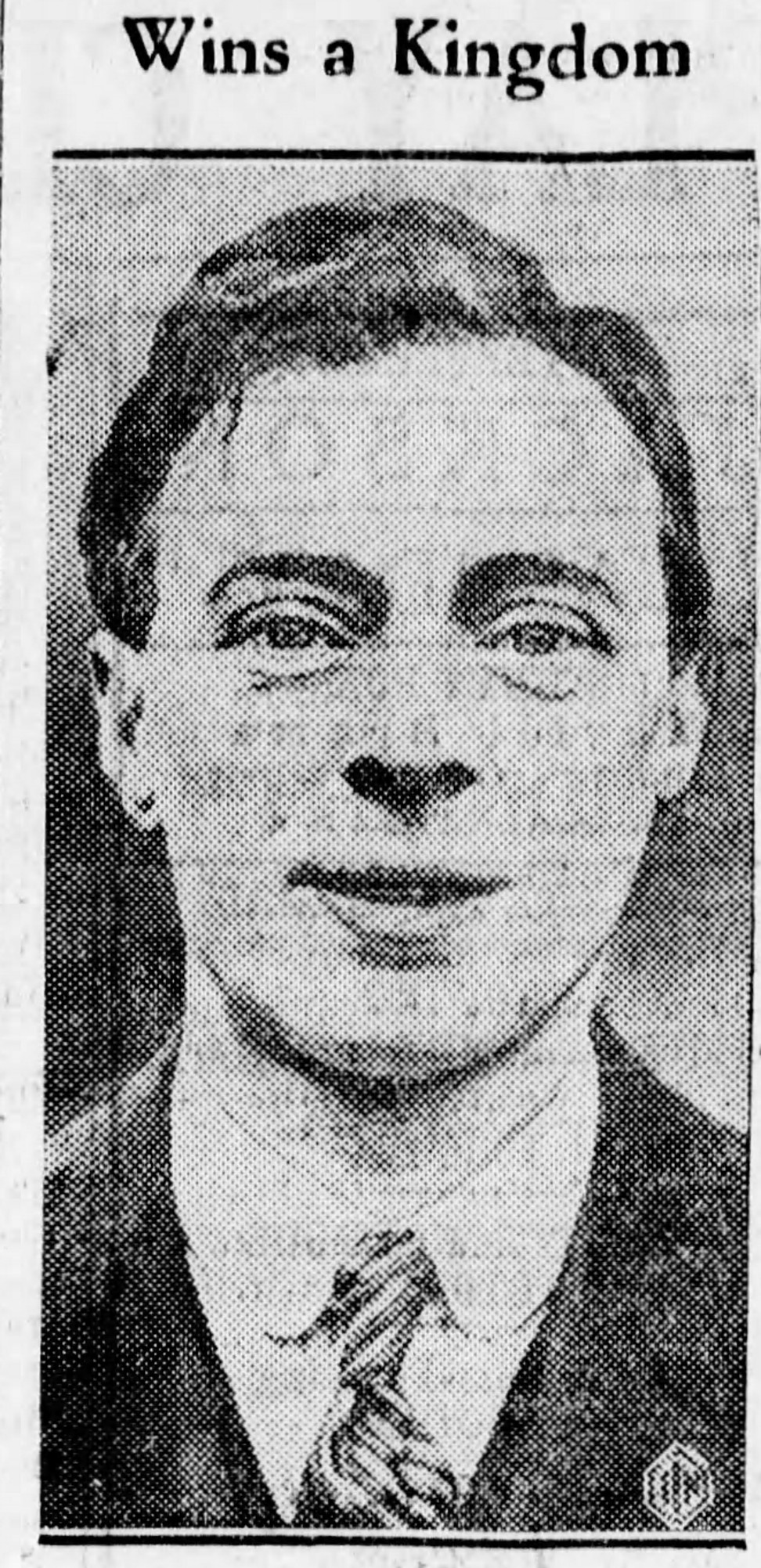

In reality, Sheldrake was slight, with sharp features, and not dark-skinned in the slightest. He did, though, often wear a red fez. The papers made various claims: that he was a nobleman of French or Irish stock and that he had renounced his ancient title to become a Muslim. It was suggested he converted to Islam to become polygamous and have several wives. It seemed inconceivable to the newspapers that he could simply be the son of a suburban London pickle manufacturer who had voluntarily adopted Islam.

Sheldrake toured Britain giving talks on Islam. He visited small Muslim communities, such as the Yemeni former seamen in South Shields and Hull, who had grouped together in the 1860s and were subject to much misunderstanding and racism around race-related riots in 1919 and 1920. He toured Morocco in 1927 and, following a large party to celebrate the 25th anniversary of his acceptance of Islam, undertook a lecture tour of India, in 1928.

Nevertheless, Sheldrake by this time was feeling disheartened at the lack of uptake of Islam in Britain. In the early 1900s, when he had converted, there had been fewer than 300 converts in the country; 30 years later, there were still fewer than 600 among only 3,000 Muslims resident in Britain. He started to think about a future in the wider Muslim world.

Sheldrake considered launching a missionary campaign in America. Writing in The Minaret, he said he felt the time might be right for the United States to embrace Islam. He was encouraged by Muslim conversion rates in Brazil and Guatemala but, ultimately, he opted against what would have been, by any stretch of the imagination, a massive undertaking.

In 1930, The Malaya Tribune newspaper in Singapore commented that Khalid Sheldrake’s name was known in almost all Muslim countries because of the propaganda work he conducted in Britain on behalf of the faith. And, by the time the Xinjiang delegation arrived in Forest Hill, the Muslim world was familiar with Sheldrake’s part in the conversion of Gladys Palmer, better known at the time as the daughter of Lord Walter Palmer, of the Huntley and Palmer biscuits empire, and the Dayang Muda of the Kingdom of Sarawak.

At 21, Gladys had married Captain Bertram Willes Dayrell Brooke. The British Brooke family, known as the “White Rajahs”, had ruled Sarawak, on the island of Borneo, as a private kingdom for a century. As a brother of the raja, Charles Vyner Brooke, her husband was titled Tuan Muda (literally “Little Lord”). When he married Gladys, in 1904, she became Dayang Muda, and was referred to as “Her Highness” in English.

Gladys, however, never spent much time in Sarawak. A leading socialite, she relished mixing with peers of the realm, minor royalty and show-business celebrities. She discussed literature with James Joyce in Paris; attended opening nights in London with actress Ellen Terry; and toured the cellar bars of Berlin with the sexually rapacious Irish writer Frank Harris. She formed a movie company in 1922, which made a single (forgotten and lost) film. By the late 1920s, the London society columns were reporting that the celebrated marriage was on the rocks. The couple parted, with Gladys gaining a very favourable settlement.

Then, in 1932, Gladys decided to convert to Islam.

Despite her love of the social whirl, Gladys had long sought spiritual enlightenment. Born into the Church of England, she had already passed through Catholicism (having had a personal audience with the pope) and Christian Science before accepting Islam.

Being wealthy, Gladys didn’t convert in any normal way but rather, “wishing my conversion to be performed on no earthly territory”, undertook the ceremony while flying over the English Channel in a chartered 42-seat Imperial Airways aircraft. Sheldrake, having boarded the plane at Croydon Aerodrome with the Dayang Muda, performed the ceremony mid-flight, reportedly shouting to be heard over the roar of the engines.

Gladys Palmer Brooke, the Dayang Muda of the Kingdom of Sarawak, clad in quite extraordinary robes for the occasion, was renamed by Sheldrake, Khair-ul-Nissa (“fairest of women”). Visiting a mosque in Paris soon afterwards, Gladys Khair-ul-Nissa told the press she had now, after a couple of false starts, found the “perfect faith” and was planning a pilgrimage to Mecca before an extended trip to the US.

Newspapers across Europe, America, the Middle East and Asia covered Gladys’ mid-air conversion. Many Muslim readers, even in the remote far west of China, were fascinated by Khalid Sheldrake – this Englishman who had converted to Islam at just 15 and subsequently done so much for their faith and seemed so well connected. Perhaps he was a man destined for higher office? Perhaps he was the man to rule a fledgling Muslim kingdom looking for a king?

All of this was (and, of course, still is) contentious and many tribal chiefs, warlords and political factions bickered, fought and brokered alliances only to break them the next day. China was the dominant influence, though the area was contested by first the Russian empire and then the Soviet Union, just over the border in Central Asia.

In November 1933, the Islamic Republic of East Turkestan (known simply as the ETR) was officially announced by various tribes and warlords who were united in their desire to form an Islamic kingdom with the city of Kashgar as its capital. It was decidedly not to be part of either the Chinese empire or the Soviet Union.

The 150,200 sq km ETR, often dubbed “Islamestan” in the Western press, was Uygur-dominated, but with Kyrgyz and other Turkic ethnic groups included as equals. The fledgling government claimed the ETR’s population was about 2 million people.

In Kashgar, Uygur warlord Hoja-Niyaz Haji had assumed the presidency of the ETR; Sabit Damolla, the post of prime minister; and Mahmut Muhiti was appointed minister of defence. Deputations were immediately sent to key people and nations. But nobody was swift to officially recognise the ETR. The Nationalist Chinese government in Nanjing thought the whole thing preposterous; the Soviets refused to deal with religious Muslims; while Afghanistan’s King Zahir Shah was wary of annoying the Chinese.

Still, one deputation had been dispatched to London to sound out Dr Khalid Sheldrake, and there they received a more positive reception.

Over tea in his living room, served by Ghazia (formerly Sybil), Khalid Sheldrake welcomed the deputation from Kashgar. The men sat around making pleasantries, admiring Mrs Sheldrake’s prize-winning marigolds and dahlias and Sheldrake’s goldfish bowl. In Sheldrake’s telling, there was only one question: would he consider becoming the king of Islamestan, his wife queen, and the couple taking on the “Overlordship of Sinkiang”?

He told them he would … and that he would leave for Asia immediately.

Among the arrivals by the Dollar liner President Coolidge yesterday was Dr Khalid Sheldrake, the Moslem leader of the West, who is visiting Hongkong as part of his tour to meet Moslems of all Eastern lands

In 1933, Sheldrake headed east, first visiting Muslim communities in the Philippines and Borneo. He lectured on “The Beauties of Islam” at each stop, attracting – according to the Sarawak Gazette – large and enthusiastic Malay audiences. From Kuching, in Sarawak, Sheldrake headed to Singapore and then Hong Kong.

On October 3, 1933, the South China Morning Post reported, “Among the arrivals by the Dollar liner President Coolidge yesterday was Dr Khalid Sheldrake, the Moslem leader of the West, who is visiting Hongkong as part of his tour to meet Moslems of all Eastern lands.” While in the city, he gave a series of lectures, including one at the Lane Crawford restaurant.

On March 30, 1934, under the headline “King of Sinkiang”, the paper reported that “When Dr Sheldrake was in Hongkong a few months ago, he told a South China Morning Post reporter that he had been offered the kingdom of Sinkiang, but swore the reporter to the strictest secrecy, on the ground that if the news reached certain quarters, attempts on his life would most certainly be made.”

Leaving Hong Kong, he headed to Shanghai and then to Peking. In May 1934, he checked into the Grand Hotel des Wagons-Lits, near Peking’s main railway station. A delegation from Kashgar met Sheldrake at the hotel.

From the start, the Chinese authorities were nervous about just what this Muslim Englishman intended to do in Xinjiang. A very obvious police watch was kept on his hotel and on the entourage of ETR officials who came to meet him.

Upon entering his room, according to Sheldrake, the officials fell to their knees and kissed his hand, rendering him exceedingly embarrassed. They then formally requested he be their head of state. Sheldrake later told The Times of India, “I had the choice of becoming a monarch or refusing these earnest and poor people, who might lose heart and become desperate, or fall the prey of some political adventurer.”

A formal title was agreed upon – His Majesty King Khalid of Islamestan.

Sheldrake then briefly visited Japan and Thailand, for scheduled lectures, before planning to leave for Kashgar. In the meantime, the British newspapers had taken up the story – “Deserts Pickles to Become King”.

Returning to China, Sheldrake told journalists that he would proceed immediately to Kashgar and that Queen Ghazia had arrived from England with ceremonial robes run up by her seamstress in Sydenham. She was reportedly keen to become queen of Islamestan, and her sons delighted to be princes, though she regretted that she would have to forgo her regular bridge games back in Forest Hill as these had been a great comfort to her while the future King Khalid was engrossed in his books on Islamic history, preparing to rule.

Departing Peking, the king and queen of Islamestan headed 4,350km overland to Kashgar, to attend their coronation. They travelled by camel train, accompanied by their trunks of ceremonial robes and two portable metal bathtubs Ghazia had bought in Croydon.

By June 1934, however, the newspapers were reporting that Islamestan had “hit a snag”. Rumours swirled that Sheldrake was becoming king only to steal all of Xinjiang’s not inconsiderable deposits of jade; that he was a British spy; and that, if he assumed the throne in Kashgar, then Islamestan would become a “British-controlled kingdom”.

The Chinese, naturally, complained to London; London assured Nanjing that it would not tolerate a British national attempting to rule “any form of independent regime within Chinese territory”. Japan, keen on extending its own influence in the region, also lodged an objection to Sheldrake’s coronation while fellow Muslims in Afghanistan withdrew their support for the ETR under Chinese pressure.

The shaky coalition in Kashgar started to fall apart, factions split, fighting broke out across Xinjiang. Two Chinese warlords fought each other as well as any forces either once or still aligned to the ETR. But it was probably the Soviet Union’s hostility that finished off the Islamestan dream.

The Islamic Republic was part of the buffer zone between Soviet territory and British India as well as bordering Mongolia. Succeeding the tsarists, the Soviets had continued the infamous “Great Game”, vying for influence with Britain on the Indian border while being concerned about an expansionist Japan on the Soviet-Mongolian border.

Russian newspaper Izvestia hinted that Khalid’s coronation could presage a British annexation of Xinjiang in a style similar to Japan’s recent annexation and occupation of Manchuria. There, Tokyo had placed the “last emperor” Puyi on the throne as chief executive of what they now called Manchukuo. Islamestan, a self-declared Muslim theocracy effectively controlling the large strip of land bordering Soviet Central Asia, and perhaps influencing Russia’s Muslim population under the guidance of a British subject as king, was unthinkable to Moscow.

Sheldrake, deprived of access to newspapers during his long overland journey, approached Xinjiang in early August to find the ETR collapsing and its last loyal troops surrendering to what appeared to be Soviet-backed forces. The dream of the ETR was dead and Sheldrake’s dream of ruling the new state was disappearing, too – “King’s Dreams of Asian Rule Smashed”, reported veteran United Press China correspondent John R. Morris.

King Khalid and Queen Ghazia swiftly changed direction and fled with some of the deposed leaders of Islamestan towards India, and the city of Hyderabad. Once safely in the British Raj, Sheldrake explained his relocation to India to The Irish Times, “I am not ready to be the pawn of any political game or the nominee of any particular political power. For the moment I prefer to be an ‘absentee king’. I am awaiting events before actually proceeding to my kingdom.”

He would never proceed to Islamestan.

Eventually, Khalid and Ghazia made it back home to Forest Hill, her magnolias and his goldfish. China was glad to see the back of him, as was Moscow. His return averted a potential diplomatic incident for the Foreign Office in Whitehall. Xinjiang descended back into warlord feuding.

Back in England, Sheldrake gave lectures on Turkestan affairs but few were interested in somewhere too far away, too foreign and too complex to understand. He went back to raising funds for new mosques and Muslim charities in Britain. He travelled to Libya and Egypt; to Switzerland and Austria. He also went back to the family business, as a buyer of sour pickles in Turkey. During the second world war, he worked for the British Council in Ankara.

He returned to Forest Hill in 1944 and died in 1947, still technically the exiled king of a state that had ceased to exist 13 years earlier, and had hardly existed at all.