Maoism’s inherent contradictions unpacked in China scholar Julia Lovell’s new book

- Mao Zedong was a vehemently autocratic leader yet he compelled his Red Guards to dismantle the party that he himself had built

- Rebels and regimes across the globe have remade Maoism in their own disparate images

Not everyone can identify the moment their life changed, but then Julia Lovell is not most people. An internationally renowned scholar, translator and author, the 44-year-old is today one of the English-speaking world’s leading authorities on China’s modern history, literature and culture.

Almost 25 years ago, however, when Lovell was beginning her undergraduate degree in history at Cambridge University, she knew next to nothing about the country that would define her professional life.

“It was 1995,” she recalls. “At that point China and the Chinese language still felt very remote. It’s often forgotten, but between 1989 and 1992 it seemed very possible China would return to a Maoist model of economic organisation. There were international sanctions against the country.”

Lovell’s British family had no connections to Asia, and although her parents had encouraged a passion for languages, her closest acquaintance with Chinese was having learned a little Japanese at school.

So, when her degree began by surveying China’s history, Lovell was intrigued but conscious of her ignorance. This was the moment her mother pressed a copy of Jung Chang’s Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China (1991) into her hands.

“It was already a huge bestseller. People who wouldn’t normally have read about China were reading this book and saying it was an extraordinary introduction to its 20th century history through these three amazing women. I read it in a weekend and decided I wanted to know more about China.

“Pretty much the next week, I decided to switch from history to study Chinese. I found the first term very hard. I just couldn’t get the characters to stick. But something reached a tipping point after that term. It was challenging, but it really has transformed my life.”

The rest, if you’ll pardon the pun, is (Chinese) history and literature – the subjects Professor Lovell teaches at Birkbeck, University of London, where her academic interests range from architecture and sport to author Zhang Chengzhi’s journey from communism to radical Islam. Lovell has translated Eileen Zhang’s Lust, Caution (1979), Lu Xun’s Complete Fiction (1953) and Yan Lianke’s Serve the People (2005). Her books have examined China’s quest for the Nobel Prize in Literature, the Great Wall and the first and second opium wars.

Eclectic as these interests are, they can be collectively understood in the context of Lovell’s public role mediating between China’s history, culture and politics and that of the anglophone world.

“Looking at the topics I have written about, you might think they are very dispersed and diverse. But I think one of the threads running through my interests is bringing China back into global history. Yes, I try to be China-centred – using as many Chinese sources as possible and being in constant dialogue with my brilliant, talented peers and colleagues in China. But I also consider the way in which China’s interactions with the world outside its borders has shaped the nation.”

Lovell cites her approach to the book The Opium War (2011), which she hopes draws “attention to the way British Imperialism has not been at all forgotten in China but has been significantly effaced in British memory”.

Lovell’s new book, Maoism , fits neatly into this intellectual framework, at once expanding her catholic intellectual tastes, but focused, too, on China’s place in the global realpolitik. One obvious departure is that instead of considering how the outside world has helped to fashion China’s sense of self, Lovell explores how China has shaped the wider world. Although the story starts with Lovell locating Maoism’s roots in one man (Mao Zedong), one nation (China) and one relatively compressed time period – the 1930s, give or take – what shapes her narrative as a whole is a peripatetic evolution into an international ideology, spreading from China in the second half of the 20th century across Asia (including Vietnam, North Korea, Cambodia, Indonesia, Nepal and India), Africa (Tanzania, Zimbabwe) and Latin America (Peru), not to mention Europe and America.

One tiny example of Maoism’s unexpectedly pan-global progress might be my own meeting with Lovell. Mao himself might not have endorsed Emmanuel College in Cambridge as a venue in which to discuss his political philosophy, but this nevertheless is where Lovell experienced her own China epiphany, years earlier.

She arrives, in true Cambridge fashion, by bicycle, which she secures with an impressively formidable lock – a recent purchase after her previous bike was stolen. It is a more than usually busy time in the Lovell household. Only a few days after Maoism hit the shops, her husband, the award-winning nature writer Robert Macfarlane, published his own new book, Underland. With three children to look after, as well as the two academic careers, this simultaneous publication is not something Lovell wishes to repeat.

We walk through Emmanuel’s Front Court into sumptuous gardens, which prove the perfect setting for a little nostalgia.

“It was a special time of my life,” Lovell says of her student days, the fondness evident. “The last time where I could devote myself to studying. When I didn’t have a job, I didn’t have children to look after. I got the most amazing, life-changing experience learning Chinese here – 16 to 20 hours tuition a week from incredible experts in premodern and modern language and history.”

After a stroll past sun-kissed pond, gardens and a semi-concealed swimming pool, we settle on a bench beside Emmanuel’s famous Oriental plane tree, which some have estimated to be almost 200 years old. Lovell acted in open-air plays in this very spot, the tree’s weeping branches providing a proscenium arch for the stage and, in its shadier parts, changing rooms for the performers.

We begin with perhaps the biggest, and most obvious questions. Why Maoism? And why now?

Just how radical Bo’s Mao-dolatry was in 2009 can be illustrated by Mao’s almost total omission from the Beijing Olympics the previous year. “It escaped very few people that, in a ceremony which included the full range of Chinese history, from Confucius through to lime green spandex, the Mao era was unmentioned.”

When Bo was purged from the party and imprisoned following a host of scandals, Mao might have receded from view had his mantle not been grasped with such force by an even more powerful advocate.

“Xi [Jinping] quite quickly inherited the Maoist project that Bo had started,” Lovell says. “One of the big cultural and political changes of the Xi era is to actively celebrate the culture and politics of Mao.” She cites his restoration of “self-criticism” sessions, the “Mass Line” notionally inviting criticism of party officials and “of course the personality cult”.

“Like Mao, Xi Jinping could be ruler for life. It’s been much commented on both outside and inside China, where commenting is very dangerous. To many Chinese observers this represents a dangerous return to the politics of the Cultural Revolution. The constitutional restrictions had been put in place by Deng Xiaoping and were definitely part of the de-Maoification of China after his death.”

What convinced Lovell that a book about Maoism was necessary was the surprise of non-specialist commentators in the West at Mao’s returning influence.

Chairman Mao, the man behind the Little Red Book, and a warning from China’s turbulent past for Hong Kong’s future

“The assumption had been that as China turned commercial, then Mao and Chinese Communism had been sent to the dustbin of history. There was a sense that no one needed to engage with Maoism because China would increasingly become more like the West.” Lovell quotes Bill Clinton’s famously offhand conviction comparing China restraining freedom of speech in the internet age to “sort of like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall”.

For Lovell, these reactions exposed fundamental Western misunderstandings – not only of Xi’s Maoist conversion but of Maoism’s enduring global legacy.

“Xi’s revival of Maoism really pushes us to define what Maoism is,” Lovell argues. “You quite quickly realise it is not one thing. It is many, often mutually contradictory things that have been attributed to Mao during and after his lifetime.”

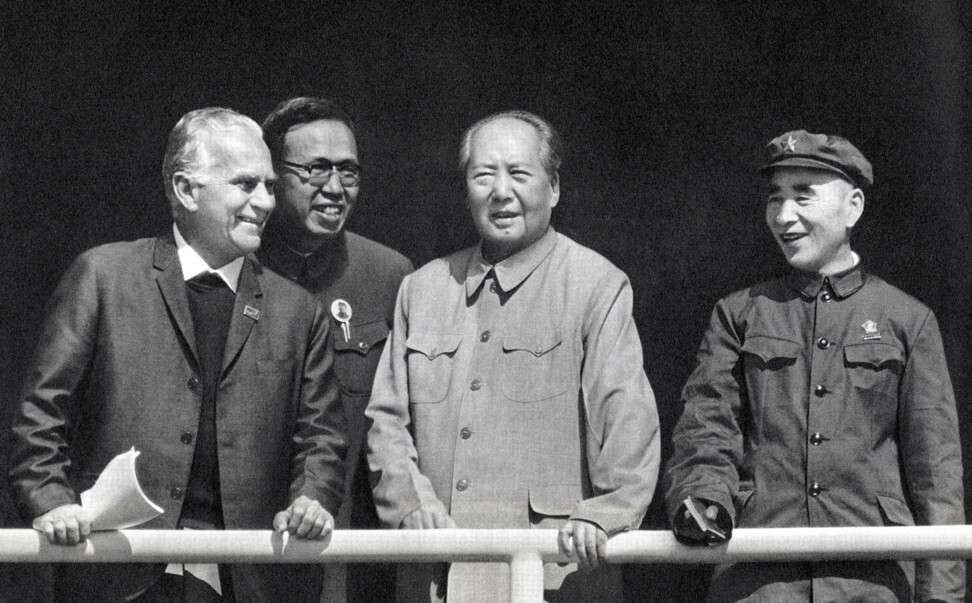

Clinton’s Jell-O metaphor works better when describing the challenge Lovell faced while trying to pin Maoism down. Is it the ideology of violent rebellion espoused by Shining Path in Peru or the student radicals protesting across Europe in 1968? Can one compare the Maoism of Vietnam’s Ho Chi Minh to that of President Sukarno in Indonesia? Can we collectively speak about Cambodia’s Pol Pot, Rhodesian guerilla Josiah Tongogara and, for that matter, Hollywood actress Shirley MacLaine, all of whom declared themselves ardent Maoists in the 1970s?

“Maoism in China was extremely intolerant of diversity and ethnic rights, and self-determination in Tibet and Xinjiang. In Nepal, however, Maoism has been seen as a set of strategies to champion the rights of the ethnically marginalised.”

As this list implies, Maoism’s protean, and often contradictory identity is partly the result of its dissemination around the world over the past seven decades. Each Maoist regime, in each country and historical moment, has re-made the ideology in its own image, adding fresh and often incongruous aspects to Mao’s original vision. Lovell wonders what Mao would have made of self-proclaimed disciples in Nepal and India defending oppressed ethnic minorities.

“Maoism in China was extremely intolerant of diversity and ethnic rights, and self-determination in Tibet and Xinjiang. In Nepal, however, Maoism has been seen as a set of strategies to champion the rights of the ethnically marginalised. This is a strange mistranslation of Maoism, not least because under the noses of Nepali Maoists were camps for Tibetan refugees from the Chinese Communist state.”

Given Mao’s intolerance for anyone misinterpreting his word, did he intend his vision to be so malleable?

Lovell points out that, as early as the 30s, Mao was arguing that the Chinese Revolution would be relevant internationally. And aside from Mao’s own “little red book”, arguably the most important publication in Maoist history was Red Star Over China (1937), written by American journalist Edgar Snow, albeit under Mao’s beady-eyed supervision.

Nowhere is this one-man personality clash illustrated with more devastating clarity than in the Cultural Revolution. One can see both Mao’s jealous defence of his own power and the most catastrophically extreme manifestation of his advocacy of violence as a political weapon: what Lovell calls “the vast human cost of his rule, how devastatingly careless he was with the lives of many Chinese people”. She continues: “Mao incites millions of people, especially star-struck youth indoctrinated in worship of him, to smash the party leadership which he feels has turned counter-revolutionary and conservative. It is a profoundly contradictory moment unparalleled in the history of global communism. A leader mobilising his own personality cult to smash the party he has built.”

Xi’s careful separation of what he considers Maoism’s wheat from Maoist chaff is typical of its broader history. Perhaps only one other Maoist regime came anywhere near to replicating the schizophrenic collisions of the Cultural Revolution: the Khmer Rouge, which destroyed its own power base through self-defeating purifications and purges.

Otherwise, Maoism’s fundamental dichotomy between stability and disorder produced two separate strains. Regimes in North Korea, Vietnam and Myanmar have aspired to the earlier, systematic Mao. The later, wilder incarnation appealed to Peru’s Shining Path and insurgencies in Tanzania, Ghana and Zimbabwe fighting British rule.

“One very important aspect of the Maoist toolkit is this idea of voluntarism. If you believe you can do something, you can do it. He preached that any country, however poor or backward, could transform its destiny if its people believed that they could. Enthusiasm and revolutionary zeal, he believed, are more important than material superiority or weaponry. It’s quite easy to see how that would appeal to poor and developing countries who had suffered at the hands of colonialism or repressive governments.”

Arguably the best example of Maoism’s persistent, even obstinate appeal, Lovell suggests, is Nepal’s Maoist Party, who briefly ruled the country in 2008. The origins of this revolution date all the way back to the Nepalese Mao-dolatory of the 60s. “It showed how ideas sink into the permafrost. And then, at a particularly timely moment, people enthusiastic about those ideas decide the time is right for insurgencies which can transform the destiny of the country. Even their detractors would find it hard to deny that the Maoist civil war was the main factor in ending the Hindu monarchy after 2006.”

Lovell’s book tells so many stories that Hong Kong hardly warrants a mention. One event she would have liked to include was the pro-communist riots of 1967, an example she says of the “turbulence of the Cultural Revolution spilling over to Hong Kong”.

The broader backdrop to the protests was, Lovell says, “the absolutely appalling state of labour law in Hong Kong at the time. I think British officials themselves felt Hong Kong labour laws in the 1950s were about 100 years behind – at the levels of Victorian England”.

The violent upheavals, which included “a radio presenter who criticised the left-wing radicals in Hong Kong being burned to death in his car”, had a profound impact. As well as compelling the British administration to improve its welfare policies throughout the 70s (the reforms of governor Murray MacLehose), they raised questions about Britain’s legitimacy in ruling over Hong Kong.

“Hong Kong wasn’t just this temple to modernity and global finance. It was this extremely problematic place in terms of its social divisions and segregations.”

This explains Mao’s intriguing but deliberate decision not to take back Hong Kong. “Mao wanted it to serve as a listening post. It was important for business, intelligence and security (for example, getting people secretly in and out of China), but also for getting the cultural story of mainland China out.” For example, the 1954 opera-movie Liang Shanbo and Zhu Yingtai, which was hugely popular both in Hong Kong and in Southeast Asia, was the first colour feature film produced in China, and was used by Zhou Enlai to promote soft power at the Geneva conference in 1954 (the premier introduced it to foreign diplomats as “China’s Romeo and Juliet”).

Mention of these archives reminds me to ask Lovell about her experiences as a scholar researching in China. She begins by emphasising the extraordinary work undertaken by Chinese scholars, who have devoted long periods of their lives, measured in years, working in historical archives to uncover valuable information. She illustrates just how valuable these findings are by pointing out that one archive (of material from 1949 to 1965) declassified by China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 2003 has now been closed again.

“A major challenge for China’s party and government is: can it show itself to be more tolerant of diversity?”

“I chose a bad time to start writing the book,” Lovell says, with a smile. “But the time hasn’t become better. It has become worse, I guess. Probably the best moment to write the book would have been in the 2000s. Although the same controls existed in terms of monitoring history and expression, it was somewhat less tense than now, particularly for access to archives.” Oral interviews have also become harder to conduct than they were before 2012, “because there is more anxiety about talking to foreigners”.

“The Mao era has always been sensitive, but it became an issue of red-button sensitivity because of Xi Jinping’s own bloodline – namely, that his political legitimacy derives from the fact that he is the son of one of Mao’s own revolutionary comrades.” Lovell quotes Xi’s admonition that historians must not engage in historical “nihilism”, which includes criticising the Mao era.

While this tightened political control and centralised party power under Xi might be indicative of a resurgent Communist Party, Lovell argues this is not the whole story. “There is another side of that coin. Increasing control doesn’t mean the party is more powerful. It can mean that it’s insecure.”

When I ask what issues concerning China are uppermost in her mind, Lovell names two.

“I hope more people will study Chinese seriously. I hope people will see it’s not just something that might be useful, but something really worth engaging with”

“A major challenge for China’s party and government is: can it show itself to be more tolerant of diversity? In recent months, the world has been shocked in particular at one manifestation of the contemporary party-state’s intolerance: the anti-Uygur surveillance regime it has built in Xinjiang, alongside a network of indoctrinating internment camps. It’s the responsibility of sinologists to draw attention to this crackdown, a massive curtailment of human rights that some have named cultural genocide.”

The second issue is just as pressing: climate change, and China’s vital role in navigating the world towards a sustainable future. This is partly a domestic matter, as China continues to industrialise, become more commercialised and launches globe-altering projects such as the Belt and Road Initiative. But with Donald Trump rejecting the Paris Accords, China’s voice is vital in reminding the West of its responsibilities, not least in Asia.

“The West has generated most of the [environmental] destruction while parts of the world like South Asia, Malaysia and Indonesia that have not enjoyed that modernisation suffer the worst effects.”

On a professional level, Lovell has embarked on a new project: an abridged English translation of Journey to the West, which she describes as one of “the great works of premodern Chinese fiction”. In its own way, it is as challenging as writing Maoism: Lovell has had to find a way to translate a story whose narrative roots are in oral epic and whose universe is “remote and strange”, not least in its references to religion and politics. Coincidentally, Journey to the West was a favourite book of Mao. “It was interesting as I went along to think, ‘That’s what Mao was relating to.’”

“I hope more people will study Chinese seriously,” she says. “I hope people will see it’s not just something that might be useful, but something really worth engaging with. The study of China and Chinese does reward long-term engagement.”

Lovell’s own story is proof of that.

“I hope anglophone students will study Chinese with the same intensity that Chinese students bring to their engagement with English. There is still a huge cultural deficit. Most Chinese people know far more about Western cultures, especially anglophone ones, than is true in the opposite direction.”

A few more Julia Lovells would help restore a balance.