Dead, drunk or driven insane: life for a British consul in pre-1949 China

From 1843 to 1949, the typical British consul’s time in China was beset by social isolation, mental illness, alcoholism and disease, often in ‘alien, remote, and hazardous surroundings’

Wars, floods, murders, terrorism, suicides, revolutions and rebellions, were just a few of the troubles facing British consular officers in volatile pre-communist China, dramas commonly met armed with nothing more than a calm presence and recourse to a pen. Life for a British consul could be a dangerous affair.

By imperial desire, China was a closed society until 1843, when it was forced by treaty to open its borders after its defeat by the British in the first opium war. Before that, foreigners had been largely unwanted and excluded. The country became closed to the world again in 1949, with the founding of the People’s Republic. But in between existed 100 years when a weakened China endured a semicolonial era, with large slices of its major ports and cities given over to foreign rule in the form of concessions and settlements for the purpose of trade, much of it tea to Britain.

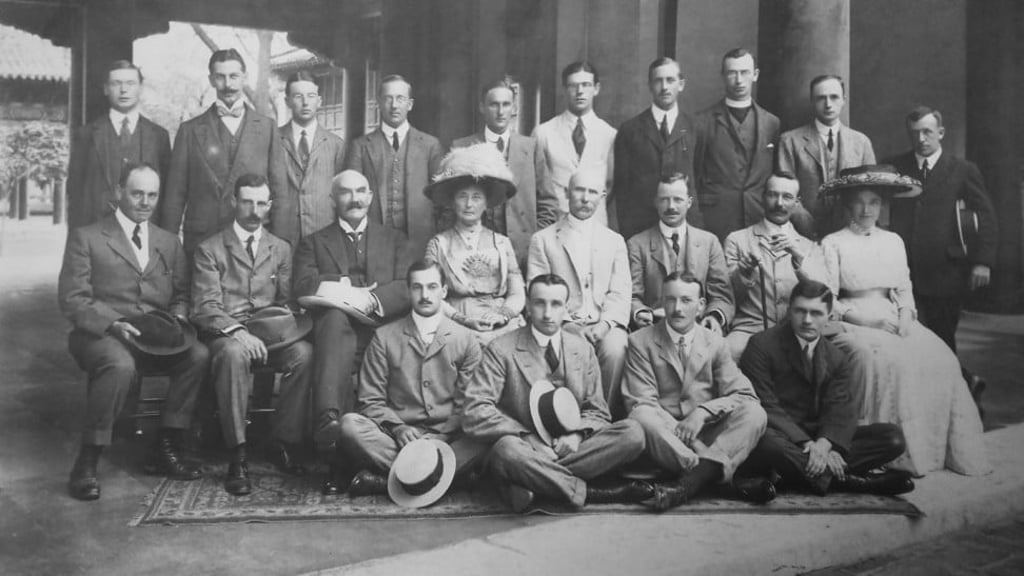

Into this newly opened country, the Foreign Office sent its gutsy representatives: the British Consular Service in China, or the “China service” as members fondly referred to themselves.

China was never an easy ride. In the early years, consular work involved an element of unintentional pioneering. Later it was often a case of simply surviving. Travel through this “medieval” country, as many Europeans described it, often involved traversing immense distances over or around deserts, mountains, plains, coasts and seas, through baking sun and freezing winds.

Recruits came largely from minor public schools. They were the sons of doctors, merchants and army officers. Many were attracted by the exotic lure of the Orient, others pushed by a lack of prospects at home, or a desire, as one retired consul described it, “to avoid the drabness of commuting each day to work on a train, wearing a bowler hat”.

Candidates who passed an entrance exam in London were sent on the long sea journey for training in Peking. One such recruit in the 1880s recalled steamships as far as Shanghai (with a change at Colombo, Sri Lanka). Thereafter the transport got smaller: a crowded coastal steamer to Tientsin (now Tianjin), followed by a Chinese junk up river to Tungchow (Tongzhou). The last 15km to the walls of Peking were covered inelegantly astride a donkey (the rail line did not arrive until much later).