Taiwan’s brutal White Terror period revisited on Green Island: confronting demons inside a former prison

- Thousands of political prisoners were incarcerated in a notorious prison under Chiang Kai-shek’s rule

- The Human Rights Art Festival at the former penitentiary is helping Taiwan reconcile its past

Green Island is a 15 sq km islet bursting from the sea off the coast of Taitung, a small city on Taiwan’s wild southeast coast. Long the domain of the Amis aboriginal people, the island saw the Han Chinese arrive in the early 1800s, and brand the volcanic outcropping “Fire-Burned Island”, in reference to the fires islanders would light to guide fishing boats to shore, long before the lighthouse was built, in 1939.

Most of the 3,000 or so permanent residents live near Nanliao Fishing Harbour, which attracts legions of visitors every year, mostly thanks to the coral reefs that encircle the island. Yet what the local tourist bureau dubs a “snorkellers’ paradise” is overshadowed by the darkest expression of totalitarian rule in Taiwan, namely the “White Terror”: decades of disappearances, imprisonments and executions under Chiang Kai-shek’s martial law.

Three hundred kilometres away, in the capital Taipei, Chiang’s statue stands tall inside his eponymous memorial hall, which remains a place of pilgrimage and veneration. But during his presidential tenure, the generalissimo ruthlessly targeted supposed communist sympathisers, critics of the regime and just about anyone who dared imagine that Taiwan might be the subject of its own story.

Of the 140,000 White Terror victims, 20,000 would be incarcerated in two notorious Green Island prisons, the New Life Correction Centre (1951-1965) and later, the Reform and Re-education Prison (1972-1987).

The brutality carried out on this little rock would foreshadow Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution across the strait, but would be largely overlooked by the United States and its cold war allies, who saw the spectre of communism as a far greater concern.

Many Taiwanese date the beginning of the White Terror to a quashed rebellion on February 28, 1947, known as the 228 Incident. But it was in the 1950s and 60s, after 1.5 million mainlanders poured onto the island following Mao’s Communist Party takeover of China, that Chiang’s ruthless campaign for his ruling Kuomintang (KMT) to curb criticism and silence dissent accelerated. The terror would only end when Chiang’s son, Chiang Ching-kuo, lifted the longest imposition of martial law in the world at the time, in 1987.

Like many rock formations throughout Taiwan, Green Island’s strange volcanic outcroppings are bestowed symbolic names. The General Rock, a silent sage looking out to sea, unwittingly expresses the negligence of those who turned their backs on some of the worst atrocities in modern Taiwanese history.

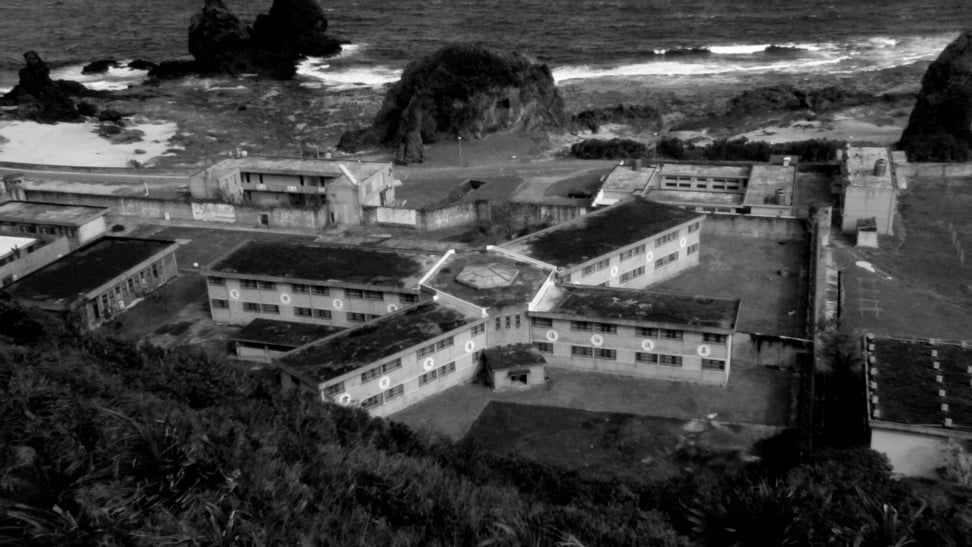

Behind the General’s back sprawl the barbed-wire fences of Oasis Villa, the misleadingly welcoming designation of the Reform and Re-education Prison, part of a much larger prison complex where hundreds of thousands of state enemies were incarcerated, and thousands executed.

Hong Kong-based Australian Martin Merz, a retired merchant turned Chinese literature translator, visited Green Island as a student in 1974, when the White Terror was underway, and recalls, “I first came with two American classmates when I was studying Chinese. It was not a tourist destination back then because it was known to be the location of the most dreaded no-return political prison. We were the only people who took advantage of the mineral hot springs in the rock pools at the beach and there was no admission price. I did see some frail old men who farmed deer and later learned they were unable to go back to Taiwan, or [mainland] China for that matter, because they were still considered dangerous.”

Open to the public as part of the Green Island Human Rights Culture Park as of 2001, this sombre enclave on an otherwise warm holiday island remains haunted by the ghosts of inmates. “Such a beautiful setting for the final resting place for so many anonymous tragic souls,” says Merz, who returned this year, taking in the scene inside the prison he couldn’t have entered four decades ago. Today, faded murals remind viewers to love Taiwan, or illustrate model KMT soldiers preparing to liberate their Chinese brethren from communism. Open cell doors reveal tiny rooms, the last homes many would ever know.

Under a title drawn from the common detainees domicile on Green Island, “Visiting No.15 Liumagou”, the first Human Rights Art Festival, opened on June 15, aiming to redress the past, or as curator Sandy Lo Hsiu-chih puts it, “exploring that which has been through three different perspectives, memory, place and narrative”.

Lo was born in 1968, in the middle of the White Terror, and believes “this exhibition expresses that Taiwan has grown mature enough to confront its demons”.

“It’s not that Taiwan is perfect but we recognise the need to reconcile […] there’s a real sense that we can move forward. It’s a world apart from when I was young.”

In a wing of the prison-cum-museum I find artist Tsai Hai-ru discussing her large-scale outdoor work with members of the media and fellow artists. Tsai has made a 3D sculpture of the Chinese character qing, meaning “clean”, “purge” or “clear”, for a work titled Clean Plan (2019). The nearly three-square-metre steel character bears scarred holes that appear to have been slashed open by lightning or an earthquake.

“I hope that political victims and their families will write down their words of pain, regret, thoughts or remorse on a piece of paper and insert it in the openings,” says Tsai. “The paper will dissolve over time, eaten by the forces of nature. Then some day plants will grow through the cracks, and maybe even bear fruit to eat” – a reference, perhaps, to the prisoners forced to sport the characters “Xin Sheng” (New Life) on their prison attire. Tsai’s work is particularly potent because her family was directly touched by the White Terror.

“On my father’s side, we are sixth-generation Taiwanese,” says Tsai. “My father was accused of being a spy. He was arrested in 1950 for participating in underground political activities. He was arrested again when I was nine and taken away for 10 years.”

Nearby, a former military police base has been repurposed as the exhibition pavilion, showing an animated film titled Mystery Train (2019), directed by Wu De-chuen and made in collaboration with papercraft artist Jo-han Cheng. The short film explores “the conflicting bonds between individuals, families, society and national ideology during the White Terror period”, says Wu, while in the background, a disturbing soundtrack of handcuffs clicking and wheels grinding accompanies the story of passengers aboard a train heading to an unknown destination, an allegorical narrative for those taken to Green Island without fair trial.

“I’ve always loved animation,” says the Tainan-born artist. “I remember in 1975, when Chiang Kai-shek died, I was so sad because we couldn’t watch cartoons. His funeral was on all the channels.”

Not all the artworks on display are quite so dark. Taipei-based university art teacher Hong-John Lin’s philosophy that “art should talk to the people who can listen” drove him to take a documentary approach to his work, Bio-Dictionary (2018-19), conducting field surveys and interviews with Green Island elders who still remember those imprisoned in the New Life Correction Centre.

“I wanted to look at the prisoners from the outside in,” says Lin. “What I learned from the locals surprised me. During the first phase, which lasted from 1951 to 1965, life here wasn’t as strict as it became later.

The Newlifers, as they were known, had a lot of interaction with the islanders. As part of the labour duties, they built the road and worked on infrastructure projects. Prisoners organised cultural programmes and performed for the villagers. They helped open a medical facility and taught some of the islanders new agriculture techniques. There was even a cinema they shared. Some of the islanders and inmates grew quite close.”

One discovery Lin made while interviewing the islanders was the red steamed buns villagers made for the prisoners. “It’s a local delicacy,” he says. “As they couldn’t give the prisoners traditional red envelopes packed with lucky money, they’d give them red steamed buns stuffed with seafood during the [Lunar] New Year celebrations.”

The steamed buns were served on the opening night of the festival to the artists and attendees.

“I use the motif of food as a bridge, a means of time travel,” says Lin. “You know this culinary tradition is dying out here, not many people can make them any more, so it literally gave us a taste of the past.”

One of Taiwan’s most prolific visual artists, Yao Jui-chung is showing Wan Wansui (“Long, Long Live”, 2012-23). The video installation depicts the artist in full KMT military regalia, standing in one of Taiwan’s many decaying military sites. Whether on the frontline islands of Quemoy (also known as Kinmen) and Matsu, the Police Command Headquarters on Orchid Island, or in the prison cells of Green Island, Yao acts as a devoted soldier, hoisting his fist into the air and shouting the mantra “Long Live” among the rubble, half submerged tanks and weathered battlements of a forgotten war and the fading dream of reconciliation.

“Politics is so often just a minority fooling a majority to maintain the minority’s privilege,” says Yao. “History is just the answer provided by the winner. But in the ruins you discover alternate answers.”

Politics is so often just a minority fooling a majority to maintain the minority’s privilege. History is just the answer provided by the winner. But in the ruins you discover alternate answers

Military, religious and industrial ruins are common in Yao’s work. “Among ruins I feel unaffected by the games of the powerful. There’s a certain truth in the rubble and desolation […] I was never persecuted, but I was born in 1969, in Taipei, to a mainland-born father and a Taiwanese mother, so I’ve seen both sides of the story, over the dinner table as it were. That might be why I have so many questions. Of course, I had to do military service, which was a strange experience.”

Yao, who has spent much of his artistic career investigating his roots, heritage and what it means to be Taiwanese, believes his generation has something special to say about their current, curious circumstances.

“For those of us who’ve straddled democratic reforms, we’ve seen Taiwan from both angles. For instance, in geography class at school, Beijing was called Peiping, Taipei was the capital of Zhongguo [the Middle Kingdom] and this included Mongolia,” he says, chuckling. “We learned virtually nothing of our own land.”

Yao and his contemporaries have watched a form of liberal democracy emerge in Taiwan, where “you look around at Taipei and you see a city only as flashy as a second-tier mainland Chinese city, but it’s free”.

“Anything goes, you can say what you want,” he says. “In that sense, we represent the hopes and aspirations of Han people across Asia. We’re the ones who’ve stood up.”