- In Dear Scarlet, author Teresa Wong shares her experience with the ‘black cloud’ that is postnatal depression

Lying in bed one night about five years ago, in her hometown of Calgary, Canada, Teresa Wong suddenly had an idea for a book. Pregnant for the third time in under five years, she couldn’t sleep, or stop her mind returning to the births of her two daughters, Scarlet and Eden.

Instead of feeling a warm glow at the miracle of childbirth, Wong saw nightmares of physical trauma and months of postnatal depression. “I was thinking back to the delivery room with Scarlet, and just crying,” Wong recalls. “I just couldn’t get these images out of my head. I thought maybe I should write about that.”

Ever since high school, writing had been Wong’s way of “figuring out how I was feeling about certain things”. She had tried, and failed, to complete a memoir about her own parents’ extraordinary journeys from Guangdong to Canada, where they eventually settled and raised their two children: Teresa and her younger brother, Michael.

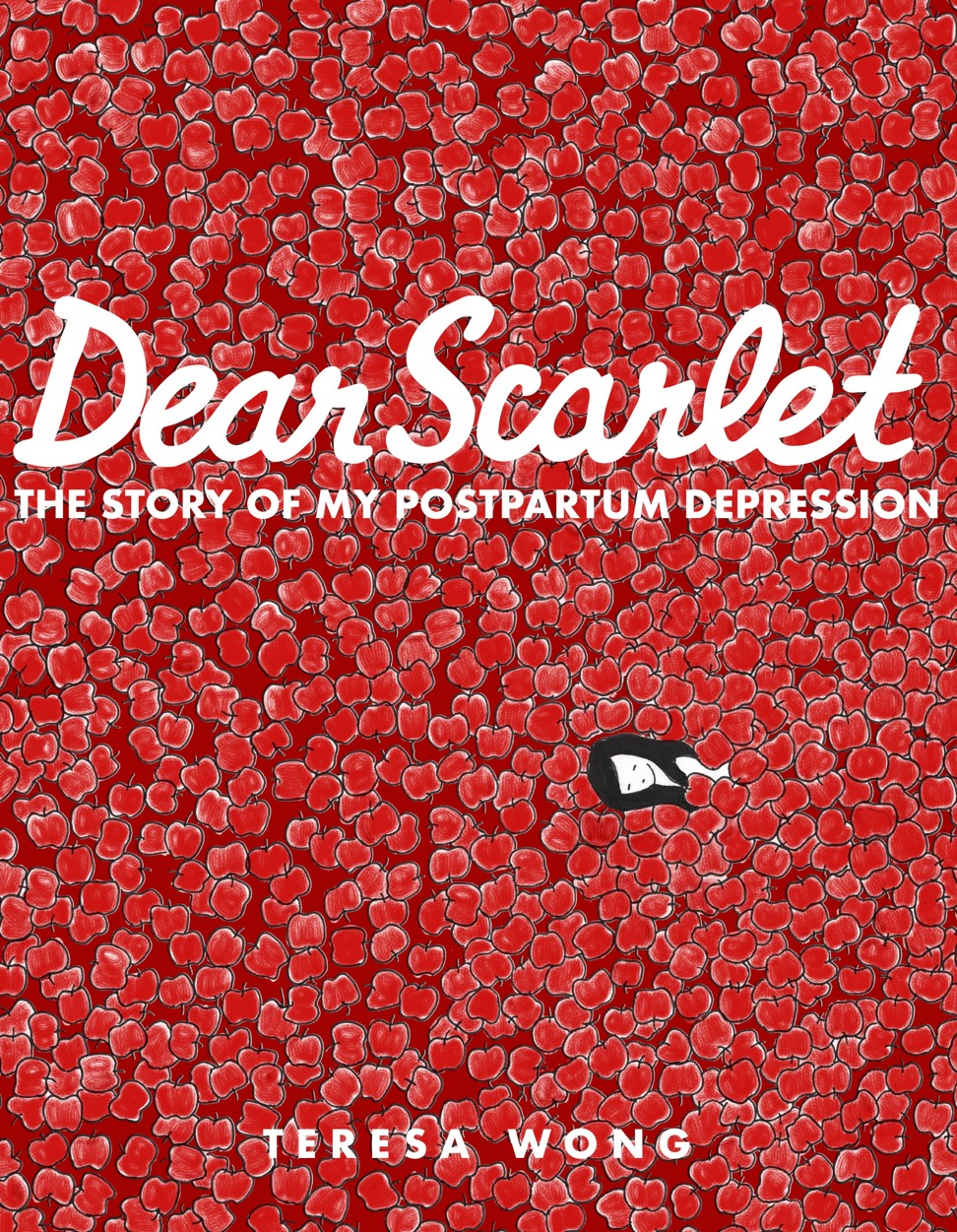

What Wong sketched on that sleepless night seemed little more than a “bunch of notes. A script. A letter, really”. And that, more or less, is what Dear Scarlet, published earlier this year, became – a letter addressed to her firstborn expressed in the form of a graphic memoir, augmented by Wong’s own rudimentary black-and-white line drawings.

“I still kind of cringe,” Wong says today. “It wasn’t a stylistic choice so much as the limits of my ability. When I started the book, I didn’t think I would illustrate it. Everyone I showed it to said it’s such a personal story, so intimate, it really needs to come from you. I said, I can only draw about 25 per cent better. Will that take away from the story?”

The simple answer is no. In addition to her candid writing, Wong’s stark, unsentimental portraits convey her isolation, the mounting psychological pressure and, above all, the silence of those dark days. They are touching and funny, if in a somewhat grim fashion.

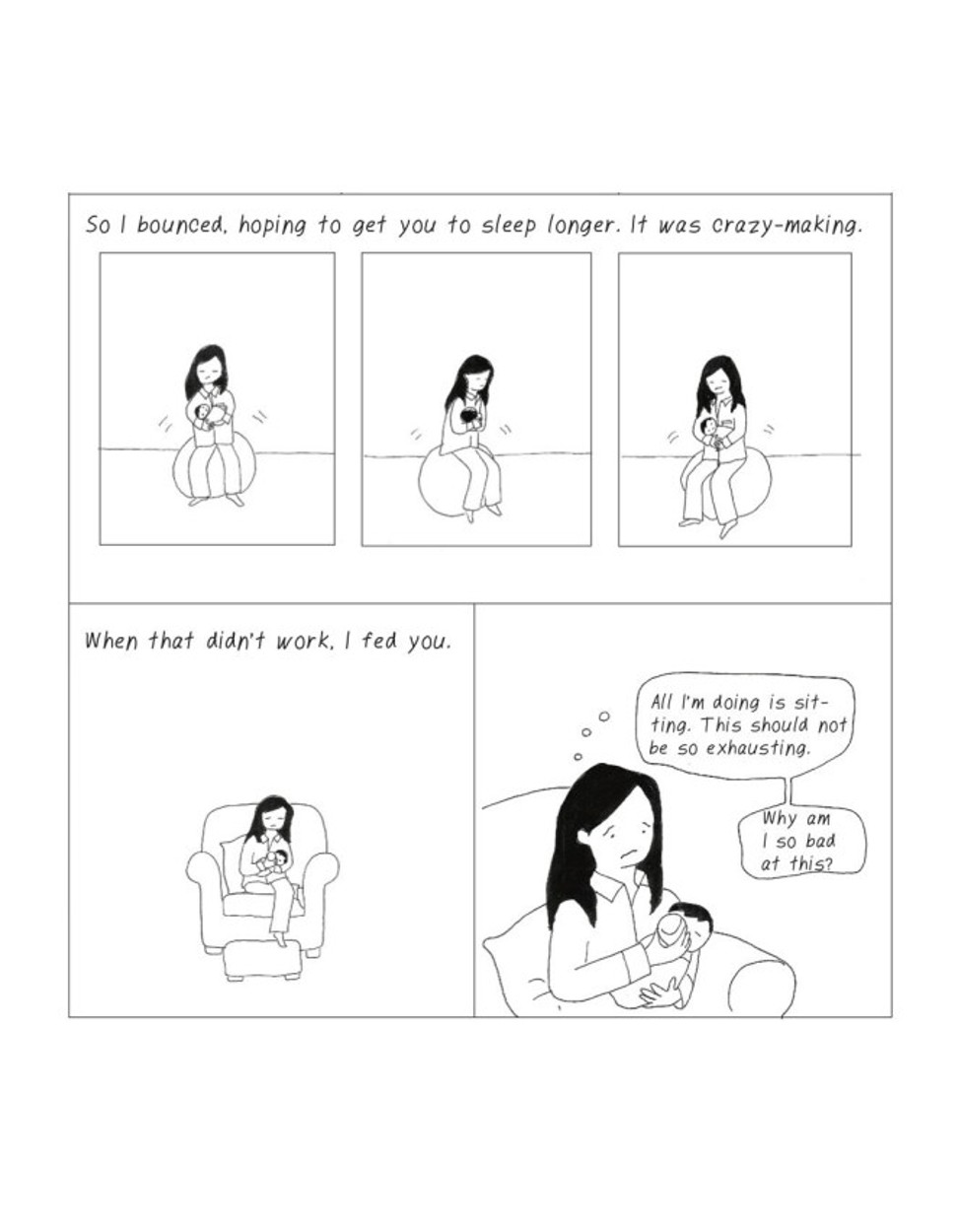

“Everything came back to me as images,” she says. “That time was so quiet. I didn’t know how to talk to [Scarlet] when I first became a mom. Nothing came naturally. Mostly I was quiet. Rock her on the exercise ball. Change her diaper. It was all in silence. What better way to convey that with a graphic narrative?”

Whether the pun on “graphic” is intentional, the result is the most harrowing, if tender of family albums, whose themes of ill health, physical pain and mental anguish are redeemed by her own survival and evident love for her children. Also secreted in this memoir are hints about Wong’s broader family history – her parents’ migration to Canada, their respective attempts to adapt to a new country, and what it means to all three generations to live as Chinese-Canadians.

Wong, 43, is at work when we talk: she is a copywriter at a digital marketing agency. There are moments when the sheer ordinariness of the backdrop feels eerie. Colleagues wander the office, confer and chat, take calls or, for the most part, stare intently at computer screens as Wong tells her story of despair, loneliness and gradual recovery.

We begin with Wong’s own personal backdrop: the story of her parents’ lives in China and separate journeys to Canada. In Dear Scarlet, this occupies just three frames:

July 1975 – Poh-Poh [Wong’s mother] arrives in Canada to meet her husband for the first time. Winter 1975 – Pregnant and working in a factory while taking ESL classes. July 1976 – I am born. Your [Scarlet’s] Uncle Mike follows a short 22 months later.

The story that surrounds these bare facts is startling and dramatic. “Sometimes I joke that I have Mao Zedong to thank for my life,” Wong says. “Had he not caused such turmoil when he took over in China, my parents would probably not have met at all.”

Chen Xiwo grew up during the Cultural Revolution, but calls these ‘absurd times’

Wong’s father made it all the way to an island near Hong Kong. “I couldn’t tell you which one. He describes it as a small fisherman’s island.” Her mother was picked up by Hong Kong authorities. “Because she had relatives in Hong Kong, they brought her there and she was granted asylum.”

“They started writing letters back and forth,” Wong recalls. “They made one phone call, because it was very expensive. My father basically invited her to come to Canada.” Arriving in July 1975, she had roughly two months to decide whether she wanted to marry him before her visa ran out. “She did. By the fall, she was pregnant with me.”

I wasn’t expected to do much around the house, because they wanted me to focus on my schoolwork. That’s partly why the transition into motherhood was so difficult. No one expected me to have babiesTeresa Wong, author

Wong laughs ruefully when I ask whether it all worked out. “Well, the relationship isn’t the best,” she says, but “it worked out for me”.

The Wongs worked tirelessly to make a better life for their children – her father as a mechanic, her mother in a coat factory. “They poured everything into me and my brother and had high expectations for us to do better in life than they did.” These expectations centred on academic achievement, which suited Wong perfectly. “I rose to the occasion. I think it was a little harder for my brother. I wanted to do well and found myself excelling at school. It played into everything that I thought I was.”

What these expectations did not include was any form of domestic responsibility.

“I didn’t cook or clean. I wasn’t expected to do much around the house, because they wanted me to focus on my schoolwork. That’s partly why the transition into motherhood was so difficult. No one expected me to have babies, run a household and do laundry. It was all school, school, school – get a good job.”

This is not to say her childhood was without challenges. Wong talks about her experiences of racism, which she describes as “mild”: “Little kids on the playground calling names, which everyone who is different has experienced in some ways. While the names were specific to my culture, it didn’t seem targeted at Chinese people.”

If anything, the reason she was a loner had more to do with her scholarly ambitions than her ethnicity. “I didn’t have a lot of friends, but I don’t think that’s because I was Chinese. I think it’s because I was the biggest nerd.”

Where the cultural differences between Canada and China had a greater effect was at home. Wong describes her parents as fairly traditional. “They spoke to me only in Chinese, and they still do. I have maintained the language, even though my Chinese is that of a little kid’s Cantonese. There was a cultural barrier and language barrier by the time I was an older child. I had lost a lot of my Chinese language. A lot of the new concepts I was experiencing I couldn’t express in Chinese.”

An obvious climactic point for these widening fissures was Wong’s decision to major in English literature at university, having previously excelled in maths and science. How did her parents react? “They did not like it,” Wong says with a laugh. “My parents really hoped I would be a lawyer or a doctor or a scientist. Accountant even.”

But while they expressed their displeasure, they did not stand in her way. Wong eventually found a middle ground, putting her love of writing to use in a marketing career, and trying her hand at more personal essays in her spare time. Indeed, she was writing a memoir about her parents when she became pregnant for the first time.

“Everything changed from there,” she says. “I didn’t think about [motherhood] a lot, or at all. It was never something I wanted. Not that I actively didn’t want to. I was ambivalent and mostly nervous.”

While her mother was hard-working and diligent – “A good mother in the sense that she provided for us, took care of us and really wanted the best for us” – she wasn’t especially warm or intimate. This reserve was also a product of their widening language gap. ‘‘We never really had heartfelt talks about things because we couldn’t. She did the best she could with what she had,” Wong says.

By contrast, Wong’s husband, Sunny, came from a large family filled with children, and couldn’t wait to start one of his own. “He has always loved children. He never pressured me, but he wanted them.”

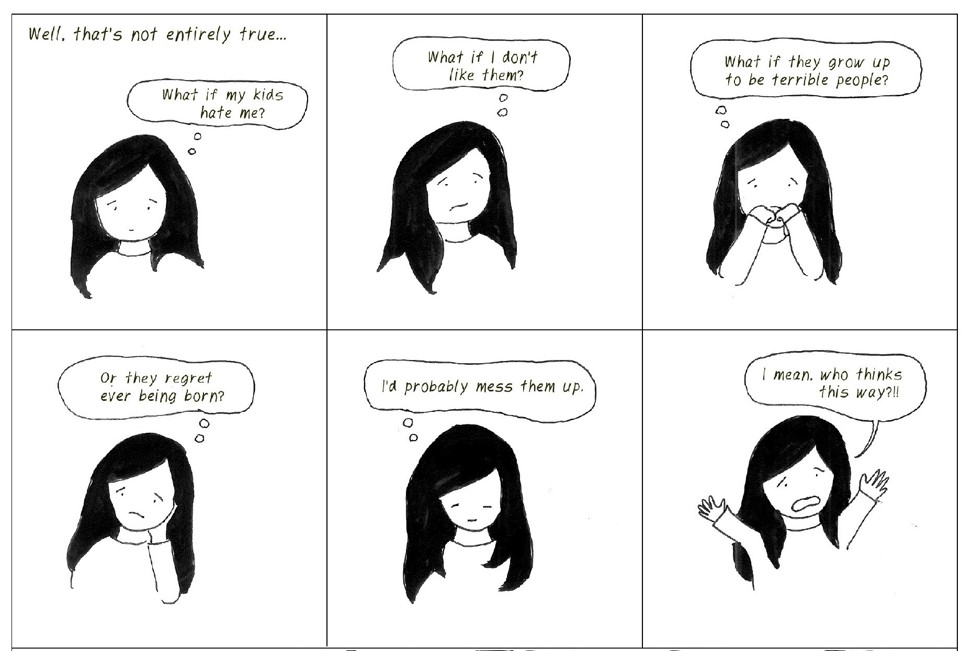

With the benefit of hindsight, Wong wonders whether her anxieties about becoming a mother were a subconscious recognition of her own unacknowledged struggles with mental health.

“I had been through some bouts of clinical depression before as a teenager and a young adult, but undiagnosed and untreated. Looking back, I know I had depression, but I didn’t know what was going on. I thought it was just life.”

I didn’t know if this was a normal thing that everyone went through. I thought it was something deeper. When I expressed that to my doctor, she told me it was normalTeresa Wong

This same dismissal – “It was just life” or “I thought it was normal” – recurs throughout Wong’s story, including in her account of her experience of postnatal depression: “I didn’t know if this was a normal thing that everyone went through. I thought it was something deeper. When I expressed that to my doctor, she told me it was normal.”

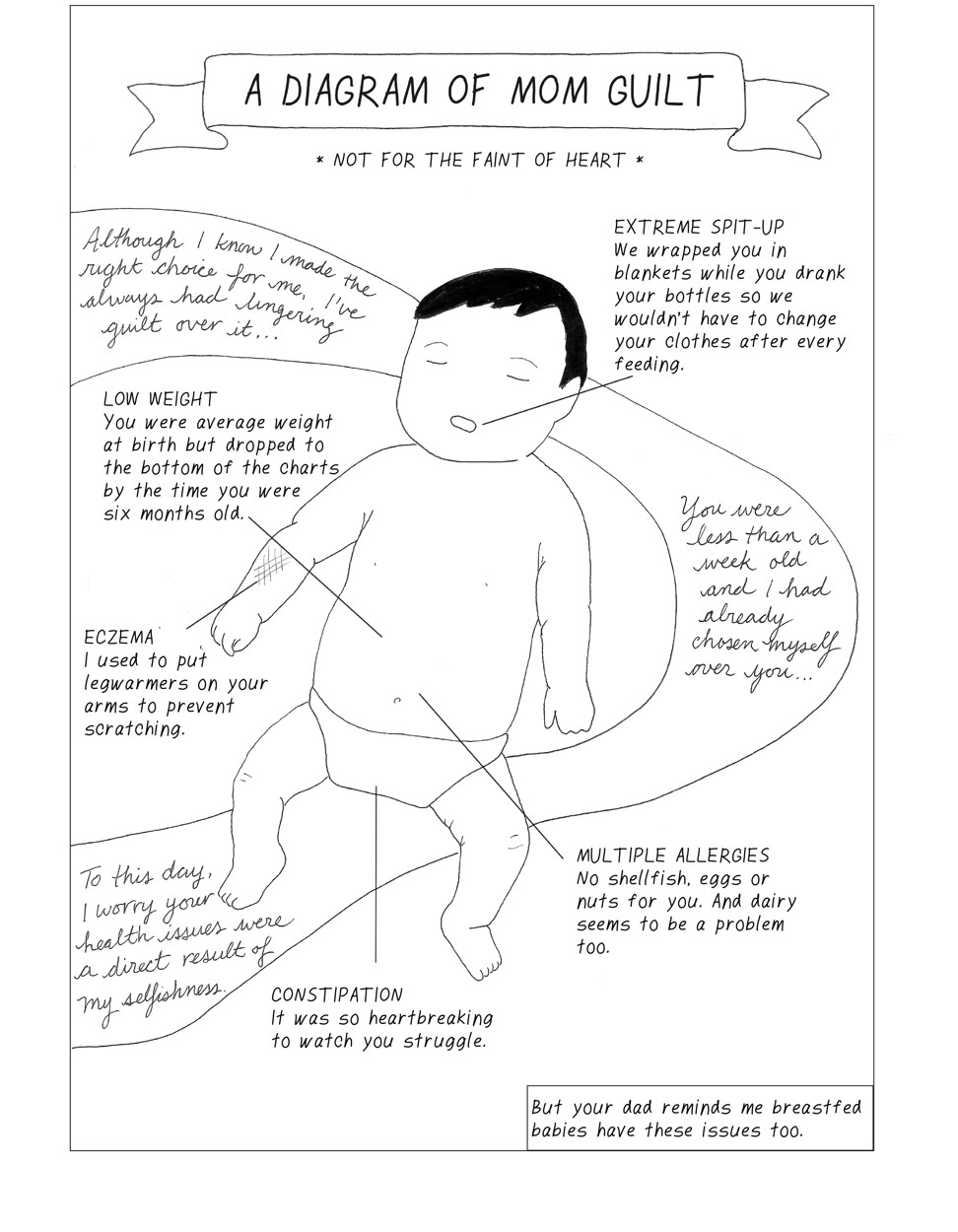

One could read Dear Scarlet as a scathing critique of medical establishments that continue to underestimate the impact of mental health issues in everyday life, including parenthood. “The baby blues happen to a lot of women and it seems like a normal thing,” says Wong. “I don’t know where the delineation is [between that and depression]. But the baby-blues diagnosis prevented me from getting the real diagnosis that I needed.”

Wong’s story will ring bells with any first-time mothers who experience childbirth and parenthood as a bewildering shock and not the instinctive, effortless and beautiful miracle that societies and institutions across the world portray.

“Doctors and experts tell you that everything you need is in you. You just need to let nature happen and you will know what to do.” Wong pauses. “No one talks about just how much trauma your body goes through giving birth. Then you can’t even rest or recover because you have a new little life to look after. It just goes on.”

I mention my own experiences, mild by comparison, with a newborn who just won’t fall asleep, or give an already exhausted new mother a rest. Wong sympathetically hears me out, before adding her own twist.

“The lack of sleep is a huge deal. But what I have discovered about myself is that lack of sleep is almost always a precursor to depressive episodes. I lose all ability to mitigate my emotions and deal with things. It’s that fatigue, and that heaviness of never being able to get enough rest.”

Indeed, one of the first tragedies of Wong’s postnatal depression was her inability to sleep in the same room with Scarlet. “Even just having her near me at night kept my body awake and alert at all times. She had to be in her own room just so I could fall asleep. A lot of that is post-partum anxiety. Many people experience both depression and anxiety at the same time. Everything feels heightened because a life is at stake. You find yourself worried that she will stop breathing, or you are doing everything wrong, or you might drop her.”

Again, Wong accepts this is something most first-time parents experience, just not at the same intense and compulsive pitch. “I thought that was a part of normal motherhood, but not when the thoughts become obsessive or prevent you from sleeping.”

Rarely do people talk about regretting having their baby, and what it’s done to their lives. The minute you even have that thought, you think, ‘I’m a monster’Teresa Wong

Buried in this mournful story is an even darker one: how postnatal depression prevented Wong from bonding with her child. “A lot of people ask, ‘Did you fall in love with [Scarlet] right away?’ Instant love? I didn’t feel that. I felt like she was a stranger I was just getting to know.”

Postnatal depression, Wong says, “felt heavy, like I was in a fog. I draw it like a black cloud over me at all times. I felt very disconnected from people. I wish I had drawn something to represent that. A glass box and everyone else is free, and there is no way to get past the glass”.

She also reveals what for many parents would be unmentionable: regretting having a child in the first place.

“Rarely do people talk about regretting having their baby, and what it’s done to their lives. The minute you even have that thought, you think, ‘I’m a monster.’ This is not what people should think. I feel like if people talked about it, they might realise it’s not uncommon, or a bad thing to feel. You need to admit it to work through it and give yourself a little bit of slack.”

The joy of motherhood: Hong Kong women left behind by crushing depression

Dear Scarlet hints at even blacker thoughts. Did Wong ever consider taking her own life? “I sort of had a little plan,” she says quietly. “It wasn’t detailed. I wasn’t on the point of planning a suicide. I just thought it would be better for everyone if I wasn’t there, and that [Scarlet] deserved a better mother than me, somehow. The only thing that kept me from acting on those thoughts was I didn’t want Scarlet to grow up without a mother. It was just gruelling.”

Eventually, with “time and counselling and medication”, Wong managed to pull herself out of the downward spiral. After demanding a second medical opinion and receiving a proper diagnosis, she was prescribed antidepressants, which opened the door to recovery. This process was eased by a doula, who took care of both mother and daughter, and, later, by cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT): “Where you recognise your thoughts for what they are and actively try to change your thought patterns.”

“While confinement was an isolating time, I believe it was what I needed to recover, physically first of all, and then to make a mental shift. You leave society and re-enter it as a mother. Dying and being reborn. It felt like the world ended and then it started again. I love how those traditions acknowledge the hugeness around having a baby. I like how [confinement] honours birth as a momentous occasion. I had friends who had a baby and went from the hospital to Walmart the next day.”

This would not be the last time Wong’s Chinese heritage came to her aid. Dear Scarlet ends with a hymn to ngai, an almost untranslatable form of stoicism and endurance. “Ngai isn’t powerful. You just exist through a difficult time. I don’t want to draw larger conclusions. Chinese people have been through a lot and they seem particularly adept at surviving these huge things in their society. I wonder if that’s part of it. You don’t expect everything to go easily.”

This does beg one important question raised by Dear Scarlet. Having been pushed to the brink of her sanity with postnatal depression, why did Wong risk putting herself through it again, and again? The answer, at least with the second pregnancy that followed 16 months later, was that it took her by surprise. But this time, the Wongs were prepared for the worst: when Eden was born, Sunny took six months off work, they hired a doula from the start and found sympathetic doctors. This, though, did not prevent postnatal depression from striking again, when Eden was eight months old.

“It was disappointing,” Wong admits. “After all that we had done to prevent it, it still didn’t work. But it was much easier to recognise the symptoms and get help right away. It was something that wasn’t forever. It would end.”

It was this experience that drove Wong to undertake CBT and address the causes of her depression. The effort paid off with her third child, Isaac. “He was the worst sleeper. Our hardest baby. But somehow I managed not to have depression.”

The worst thing you can do to anyone with depression is to minimise their feelings. Listen to what someone is sayingTeresa Wong

Wong says these radically different experiences of childbirth have not affected her relationships with her three children, now aged 10, eight and five. “While I had a terrible time, I really love my children. I have grown through both experiences of post-partum depression. It has given me another perspective, and made me want to help other moms.”

Judging by the response to Dear Scarlet on social media, Wong believes postnatal depression is more common than people think. “The statistics in North America say about 15 to 20 per cent of women have suffered, but anecdotally I would say more.”

What advice would Wong offer anyone going through what she did? “Accept help and try to get help if you can. Prioritise your sleep. Know that other people feel this way, too, and that it’s not permanent.” She also addresses the friends and families of new mothers. “The worst thing you can do to anyone with depression is to minimise their feelings. Listen to what someone is saying.”

Of course, one could also follow Wong’s lead and write a book, something that has proved profoundly cathartic. “Once I got it down on paper that was the end. I needed to get those images and memories out of my head. The story in a way has lost its power over me. Now it exists outside of me.”

Postnatal depression is much more widespread than people may realise

It turns out Scarlet has read the book she helped inspire.

“I don’t think she understood everything. She said she liked it.” Nevertheless, the book did prompt a candid discussion between mother and daughter. “I said I was very sad and scared when you were born, but that doesn’t mean it was because of you. I was really new to being a mother. And very unsure. It got better.”

That it might prompt this sort of open exchange is Wong’s greatest hope for Dear Scarlet. “I hope it helps women like me feel seen and heard, and less alone. A lot of us have these thoughts and if no one is voicing them then you assume no one else is thinking them. That can lead to shame and guilt, and that feeds your depression.”

I ask if it took courage to put these darkest and most private feelings down on paper for the world to read. “It didn’t feel courageous. I just wrote what I thought. It’s a letter to Scarlet, too. It’s what I wanted her to know. It’s probably more intimate than it should be for a wider audience,” Wong laughs. “But whatever.”