Courtyard houses in Asia-Pacific – shaped by tradition, refashioned for the 21st century

In her book about contemporary courtyard houses in Asia, South China Morning Post design editor Charmaine Chan explores how one house saved 50 trees; one preserved history; and one allowed three generations of a Chinese family to live together in harmony

It is impossible to pinpoint the exact moment I fell in love with the idea of a courtyard house. But in retracing my design-led movements across the globe, physically and via the internet, I recall specific dwellings that ignited my imagination and built the blocks of my book, Courtyard Living: Contemporary Houses of the Asia-Pacific.

One was the architectural benchmark Schindler House – completed in 1922, in West Hollywood, California – partly because it sanctioned a “revisionist” lifestyle: architect Rudolph Schindler and his wife Pauline ate outside, slept beneath the stars and shared their home with others until the good times ended. (Eventually they would live together again, but independently, in its large studio rooms.)

Another was Alison and Peter Smithson’s groovy one-bedroom, windowless town house. Their theoretical design, entered in a 1956 House of the Future competition in Britain, featured a courtyard in the middle that provided natural light and an outdoor area overlooked by none.

The now-heritage-listed landmark, better known as the Blue Mansion, drew me into its central courtyard to deliver lessons about interior voids, the wonder of symmetry, feng shui and that ineffable substance called “qi”. For the only time in my life, I felt the energy of a building coursing through my body. Maybe it was the suggestion of feng shui perfection that gave me the shivers. Or perhaps I was experiencing in that internal yard the delectable buzz of a world contained within walls – similar to Arabic courtyards that flowered lifetimes ago and embodied paradise on Earth.

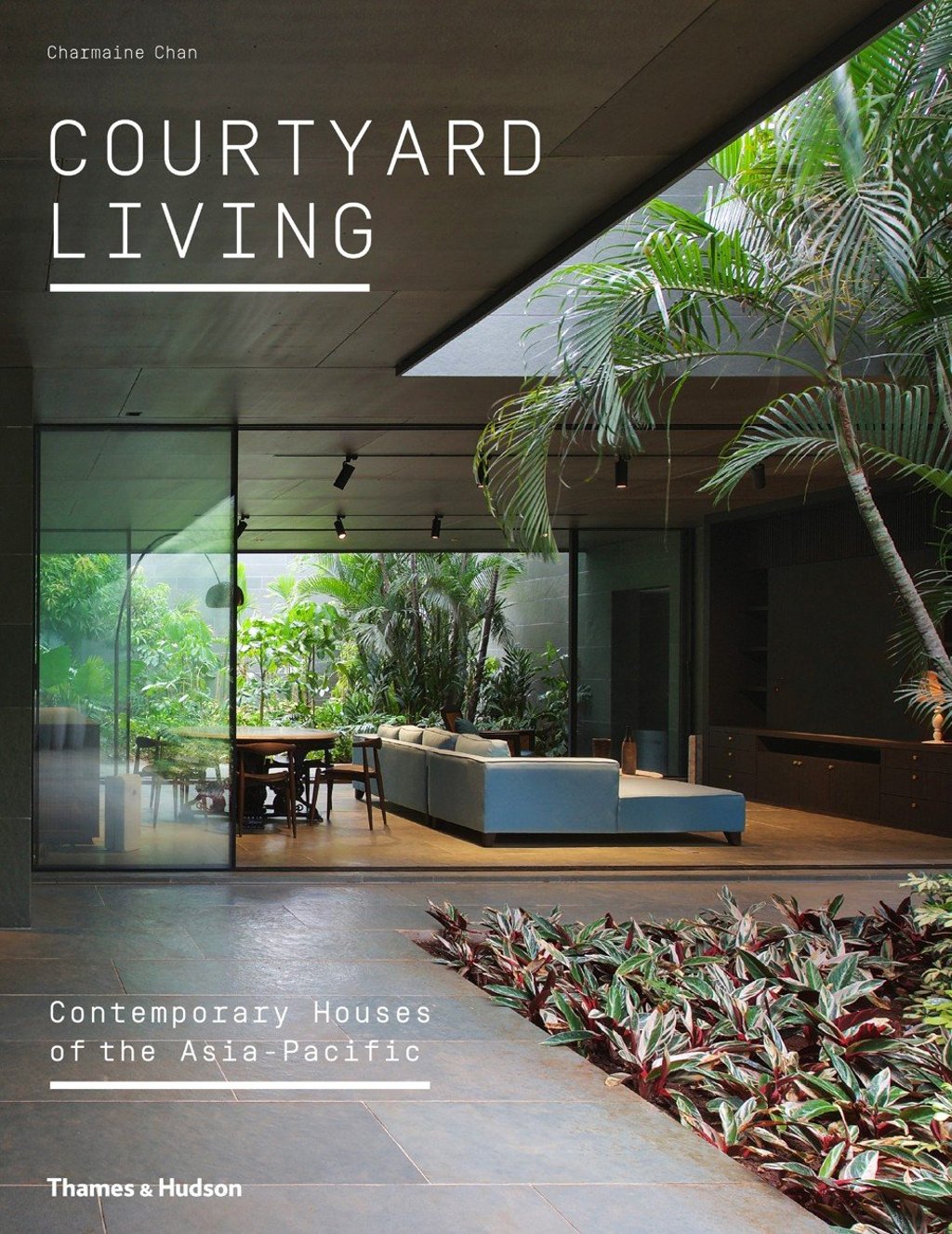

Courtyard houses have existed for thousands of years and can be found worldwide, including in the Asia-Pacific region, where styles have evolved from traditional, vernacular designs. These types of dwellings continue to be desired for many of the reasons they were built in the past: internal gardens and voids admit air and light; create social spaces; extend living areas by becoming protected outdoor “rooms”; enhance privacy; and cater to indoor-outdoor living.