He named his company after a mafia outfit from The Godfather before entering politics, ascending to the highest office and passing controversial legislation that allowed him to fire judges and opposition voices along the way

A champion martial artist in his youth, Battulga is squat and powerful, with a thickly muscled neck and ears slightly squashed from years of grappling. He wore a dark fedora, leather riding boots and a wine-coloured deel – a fancy version of a traditional herder’s robe – cinched at the waist with a broad sash. As he awaited his turn to speak, two teams of riders in red-and-blue uniforms performed an impressive display of coordinated dismounts. After remounting their steeds in one swift movement, they tore away for a lap around the stadium, a rushing eddy of pointed helmets and bouncing tails.

Battulga stepped to the mic. “Genghis Khan, the great lord and our beloved forefather,” he said, “your horses are agile, the strapping wrestlers are adept, and the archers are well-aimed.” Naadam, he proclaimed, “is an occasion that makes each and every one of us understand the essence of being a true Mongol.”

The great Khan, Mongolia’s official national hero and a man Battulga so reveres that he constructed a 40-metre-tall statue of him, was the most feared leader of his era. His forces killed millions, many in mass beheadings, as they tore across the continent. Hardly a model democrat, in other words.

Yet for most of the past three decades the country that glorifies him has been considered a star pupil of the West. European and United States leaders praise Mongolia as an oasis of liberty and capitalism, blessed with abundant mineral reserves, a young, worldly population, and a fervent desire to chart a path apart from its powerful neighbours, Russia and China.

This perception has elevated Mongolia in the minds of foreign investors, notably Rio Tinto, which is counting on the giant Oyu Tolgoi copper and gold project in the far reaches of the Gobi Desert, one of the world’s most ambitious mining developments, for much of its future growth.

Under him, Mongolia’s trajectory has shifted. Battulga has cosied up to Russian President Vladimir Putin, and earlier this year he ignited a political crisis by having legislation passed that gives him the effective power to fire judges and top law enforcement figures. He promptly used it to remove a range of judicial officials – a move he cast as necessary to fight corruption and preserve the health of the country’s democracy. “Mongolians are very loyal to the decision to have a democratic political system,” he says.

Although Mongolia’s reserves of copper, gold, iron ore and rare earths make it an attractive partner for the US and its allies, the country has been arguably more important to them as an example. Situated in an otherwise unbroken arc of authoritarianism extending from the South China Sea to Central Europe, the country rebuts the notion that some parts of the world aren’t suited to liberal values. As Battulga consolidates his position, though, some Mongolians are asking whether they can remain an exception. Oases do, after all, have a way of drying up.

The immediate forebear of modern Mongolia, the Mongolian People’s Republic, was nominally independent, but in practice it was a Soviet client state. It began collapsing in 1990, after student protesters thronged the centre of Ulan Bator. Within months there were multiparty elections, some of the first in the former communist bloc. An economic backwater even by Soviet standards, Mongolia switched to market capitalism virtually overnight, leaving many people disoriented but creating enormous opportunities for those with the instincts or connections to take advantage.

Battulga was among the latter. Raised in a tough neighbourhood on the capital’s outskirts, he distinguished himself in the 1980s as a competitor in sambo, a martial art favoured by the Soviet Red Army. Competing abroad gave him opportunities to import luxuries such as denim and VHS cassettes, and when the Iron Curtain fell he parlayed that experience into a thriving business called Genco, after Vito Corleone’s olive oil front company in the 1972 film The Godfather. Battulga’s enterprises gradually grew to include a hotel, a meat plant, a fleet of taxis and a tour agency, all in Ulan Bator.

His most ambitious business project was the statue of Genghis, an hour from the city on a plain nestled between two chains of bald mountains. Banned from public display under communism, Genghis afterward regained his status as Mongolia’s most venerated leader, his name or likeness appearing on its main airport, a popular vodka and several denominations of its currency, the tugrik.

The statue, depicting him on horseback, required 250 tonnes of stainless steel and became a statement of national pride and an offbeat tourist destination. The museum inside its base features a nine-metre-high riding boot, made with leather and 79 gallons of glue.

Battulga was elected to parliament in 2004 and became minister for transport and construction four years later. The country was about to need both enormously. Chinese demand for copper, coal and other commodities – Mongolia’s only meaningful exports – was soaring, creating a dramatic mining boom.

In 2009, Rio Tinto struck a 30-year deal with the government to develop Oyu Tolgoi’s vast deposits, becoming Mongolia’s largest foreign investor and driving competitors to scour the country for their own finds. The money spent to develop the site helped GDP grow by 17 per cent in 2011, the fastest pace in the world. As investment bankers and mining engineers poured into Ulan Bator, the dusty capital began acquiring the trappings of luxury: sushi, Porsches, a Louis Vuitton store. Officials tore down the last Lenin statue and erected one nearby to honour that accomplished capitalist Asiaphile Marco Polo.

Then, as quickly as it began, the boom was over. Commodity prices collapsed in 2014, and the tugrik plunged, making the imports to which people had grown accustomed unaffordable. Construction jobs, the livelihood for thousands of migrants to the capital, disappeared. The government had to slash civil servants’ pay, cancel infrastructure projects, and seek a bailout from the International Monetary Fund. The Louis Vuitton boutique closed.

Public fury mounted – against allegedly corrupt politicians, the wealthy, Rio Tinto. Battulga, still in parliament, was effective at stoking the mood despite his being a successful businessman and himself being investigated over suspicions that he had helped embezzle money from a railway project. (He denied wrongdoing and was never charged.) In 2016 he spoke at a rally protesting economic injustice. “Our wealth is shipped outside of the country,” Battulga complained. “Where is that money going?”

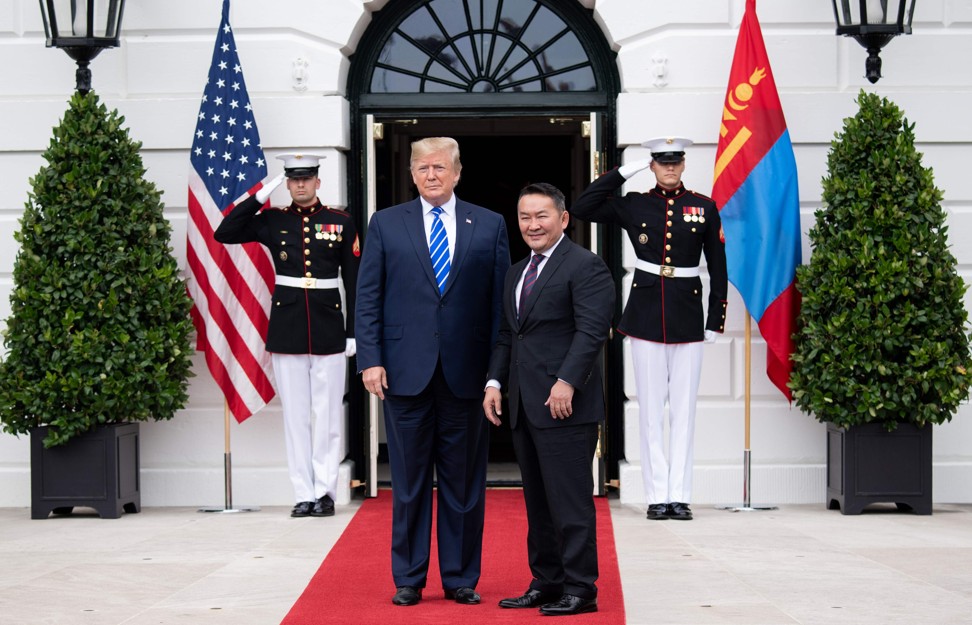

The next year, he ran for president. Although he avoided direct comparisons, there were clear parallels with Donald Trump’s campaign. Battulga portrayed himself as an outsider and an aspirational example, packaging his governing programme in the Make America Great Again-esque slogan “Mongolia Will Win”. Thanks largely to support from the poor, he surprised pollsters by finishing ahead of his main rival in the first-round vote and winning the run-off comfortably.

For the first part of Battulga’s term, Mongolia’s prime minister, Ukhnaa Khurelsukh, tended to occupy centre stage. The prime minister runs day-to-day parliamentary business while the president handles foreign affairs, judicial appointments and introduces legislation. The two men were from opposing parties, but that didn’t prevent them from cooperating. Mongolia’s main factions aren’t split on ideological lines, and Battulga draws much of his parliamentary support from Khurelsukh’s party.

Battulga seized the spotlight early this year, when he started publicly pressuring Mongolia’s prosecutor general to open a corruption investigation into the previous president, Tsakhia Elbegdorj, a Harvard University-educated liberal, claiming Elbegdorj had improperly tried to sell a vast coal deposit to foreign interests. (A spokesman for Elbegdorj denied the allegations.) The prosecutor refused, saying he needed a valid legal justification to open an inquiry.

On March 26, Battulga introduced “urgent” legislation to give the National Security Council – consisting of the president, the prime minister and the speaker of parliament – the power to fire a range of judicial officials. Legislators from Battulga’s own party boycotted the vote, criticising the law as unconstitutional. But it passed in around 24 hours, thanks to support from Khurelsukh-aligned legislators, many of whom were themselves under investigation for corruption.

Activists and other critics were apoplectic, but Battulga was unmoved, arguing the changes were needed to break a deep-state cabal protecting “political-economic interest groups”. Judges, police, and even spies were all part of a “conspiracy system that shields the illegal activities of these groups”, he told parliament.

The day after the law passed, Battulga removed the chief prosecutor who’d resisted him and the chief justice of the Supreme Court. In May, the director and second-in-command of Mongolia’s anticorruption agency – the body that had investigated Battulga over the railway project – were also removed. The following month, 17 judges, several of them on the Supreme Court, were stripped of their powers.

Battulga works in the State Palace, a leaden edifice that would seem straight from a Soviet drafting table were it not for a new facade and a statue of Genghis. A huge map of Mongolia dominates the formal meeting room where the president greets visitors, with drawing pins to represent mineral deposits: yellow for uranium, black for iron ore, and so on.

Battulga is 56, but age has barely diminished his physical presence, and he leans far forward in his chair while being interviewed, elbows perched on his knees like a coach watching his athletes compete. (Battulga is a past president of the national judo federation, which won Mongolia’s first Olympic gold medal during his tenure.) His manner is anything but Trumpian, marked by quiet and careful speech in a gravelly voice.

But Battulga presents himself, like Trump, as a man whose success has taught him how things work. “I know all the phases of the Mongolian economic transition well,” he says. “I also know that the Mongolian judiciary, prosecution system and anticorruption agency have become bodies that cover and work for certain people.”

If their influence isn’t disrupted to allow ordinary citizens to be heard and prosperity to be shared more broadly, he says, “Mongolia may go backwards, to a point where there would be many years of chaos.” He defends his law enforcement purge, arguing the three-person security council is an adequate safeguard: “I don’t hesitate to say that I made the right decision, and I will always stand by it.”

The corruption Battulga argues is rife stems from only one real source: mining. Starting in the 90s, he says, “parliament members and ministers who had access to information on natural resources and legislation pocketed the money from big mining projects”. In an implicit rebuttal to critics who accuse him of dismantling institutional safety barriers, he cites one of the world’s strongest democracies as a model for Mongolia, saying his government is studying how countries such as Norway “have managed resources for the public good”.

Discussions about managing Mongolia’s resources tend to turn rapidly to Rio Tinto. The 2009 Oyu Tolgoi deal gave the state a 34 per cent stake in the project, paid for by a loan from its developers. The interest Mongolia must return is substantial, and it won’t receive dividends until the debt is covered – currently expected to be around 2040. Oyu Tolgoi is nevertheless already crucial to the economy, with more workers than any other private employer.

To many Mongolians, foreign ownership of a key national asset is unacceptable. A 2019 survey by the Sant Maral Foundation, the country’s most prominent polling outfit, found that 89.9 per cent of respondents wanted “strategic” mines to be majority-owned by Mongolians. Only 0.5 per cent said they should be foreign-controlled.

But the costs and challenges of operating such a large and complex mine, in such a remote area, mean Oyu Tolgoi is viable only in the hands of a company such as Rio Tinto. The mine is an open pit; a planned underground expansion, necessary to tap the richest deposits, will be even more difficult to execute.

Although Battulga has no formal power over Mongolia’s relationship with Rio Tinto, he wields enormous political influence, and he is pushed to revisit the deal. He complains during the interview that Mongolia hadn’t fully understood its implications, calling it a “mistake made by an inexperienced country, relatively new to democracy”. He favours a partial renegotiation. “If circumstances change, or we realise new things, companies renegotiate,” he says. “It’s international practice.”

Battulga is more measured than lawmakers who want to scrap the agreement and start over, insisting Mongolia must honour its commitments. Revisiting the arrangement would be risky. Oyu Tolgoi is already expected to take longer and cost more than planned, and trying to overhaul the underlying agreements “would threaten the future of the project”, Rio Tinto wrote in a statement. The company said that the negotiations were conducted “fairly and in good faith” and that it’s working with the government to maximise the mine’s benefits.

Battulga and other Mongolian leaders will have to strike a balance between popular sentiment and Rio Tinto’s interests if they’re to deliver prosperity to the masses. Already, the turmoil has deterred other international miners from investing. The country badly needs their money and expertise; huge swathes of its territory have never been comprehensively surveyed. The first necessity for becoming Norway on the steppe is to pull many more resources out of the ground.

We’re almost fully dependent on Russia for oil and electricity, so we have to cooperate closelyKhaltmaa Battulga

Some of Battulga’s affinities, however, have Mongolian liberals and foreign observers worried that his preferred future looks less Scandinavian and more Russian. Chief among their concerns is his bond with Putin. Economic ties between Russia and Mongolia have been limited since the cold war – Ulan Bator is five time zones away from Moscow, and Russian companies have been far less active in Mongolia than their Chinese counterparts. But during his first two years in office, Battulga made a point of reaching out to Putin, meeting with him several times.

In September, the Russian leader received a lavish welcome in Ulan Bator, where the pair discussed trade deals and having a large Mongolian delegation attend the key event on Moscow’s 2020 calendar, a Red Square parade celebrating the 75th anniversary of the Soviet Union’s victory in World War II.

Asked if he is tilting Mongolia toward Moscow, Battulga describes the countries’ connections as both practical and emotional. “We’re almost fully dependent on Russia for oil and electricity, so we have to cooperate closely,” he says. There’s also long-standing affection for Russia among Mongolians of Battulga’s generation, for whom elite education generally meant studying in the USSR. “Russia and Mongolia,” Battulga says, “are closely bonded.”

Previous Mongolian leaders concentrated on wooing the US, notably by sending troops to Afghanistan and Iraq. (The country’s first armed foray to those lands, incidentally, was the 1258 sacking of Baghdad by Genghis’ grandson Hulagu Khan, whose horde rolled the city’s ruler in a carpet and trampled him to death.) Ties with Washington are the linchpin of the “third neighbour policy”, a long-running Mongolian effort to guarantee autonomy by cultivating relationships beyond Russia and China.

To the people responsible for selling international businesses on Mongolia, democracy remains a key competitive advantage. Dolgorsuren Sumiyabazar, the minister of mining, says that for foreign investors, “I think it’s better to reach an agreement with a system that can actually clean itself up and right its wrongs.”

Many of the people Battulga says he wants to help live in the yurt districts, home to more than half of Ulan Bator’s roughly 1.5 million residents. The districts’ existence owes to two peculiarities, one cultural and the other legal. Mongolians were largely nomadic well into the 20th century, and property ownership wasn’t really relevant; there was plenty of land to go around. Eager to build a more modern market, post-communist lawmakers created a system allowing every Mongolian to get a plot of land for free – 700 square metres in Ulan Bator or as much as 5,000 in rural areas.

Since most property nominally belonged to the state, there were few private landowners to object. One unintended consequence of the provision was that, with economic opportunity concentrated in the largest city, many nomadic families claimed a patch of land on its outskirts and never left. Few made enough money to move up the housing ladder, leaving Ulan Bator ringed with thousands of yurts – tentlike shelters used by nomads for centuries.

On a grey afternoon in a yurt district that ascends the foothills north of the city centre, it isn’t hard to see why many residents support a leader who claims he can break the dominance of the wealthy. White yurts lined both sides of a dirt track, separated from one another by short wooden stockades.

Next to each residence is a tiny outhouse, a particular inconvenience in a country where temperatures can plunge below minus-30 degrees Celsius. Peeking out above the tents are small chimneys for venting smoke from coal stoves. The average yurt burns between three and four tonnes every winter for warmth, the main reason Ulan Bator has some of the world’s worst air pollution.

To the side of a small hill stands an angular one-storey structure, constructed with a skeleton of blond wood and clad in translucent polycarbonate panels. The building is a makeshift community centre, one of several attempts made by a local non-profit organisation called GerHub, with help from designers at the University of Hong Kong, to improve the districts. Despite promises by successive generations of politicians, no one else has done it. “The government has sort of frozen,” says Badruun Gardi, GerHub’s founder. Even at the height of the mining boom, “there was this large portion of the country that wasn’t benefiting, and in some ways people’s lives were getting worse”.

Even those who helped bring about Mongolia’s transition to capitalism express amazement at how far the country has come. Dambadarjaa Jargalsaikhan and Luvsanvandan Bold were pro-democracy activists in 1990, narrowly escaping arrest after they postered Ulan Bator’s main drag. Now they’re part of the establishment: Jargalsaikhan runs a respected think tank while Bold sits in parliament and leads a political party.

Sitting in the restaurant of the communist-era Ulan Bator Hotel, they remark on Mongolia’s uniquely independent path. Both men share Battulga’s stated interest in seeing prosperity shared broadly within the current system. “When a very few people become truly rich,” Jargalsaikhan says, “and the masses get pennies, not even toilets; that makes people unhappy.” They are nonetheless deeply concerned about Mongolia’s direction. “What’s happening in Hungary and Poland, similar things are trying to be happening here,” Jargalsaikhan says.

“Nobody wants Mongolia to keep democracy,” Bold chimes in, alluding to the country’s neighbours. “I’m not even sure about Western countries. Dealing with a dictator is much easier.”

Text: Bloomberg Businessweek