- Since 2014, the world’s largest maker of freight wagons and passenger carriages has won US$2.6 billion in contracts in America

- Antagonists argue that its coaches will be used for espionage, an economic and military security concern

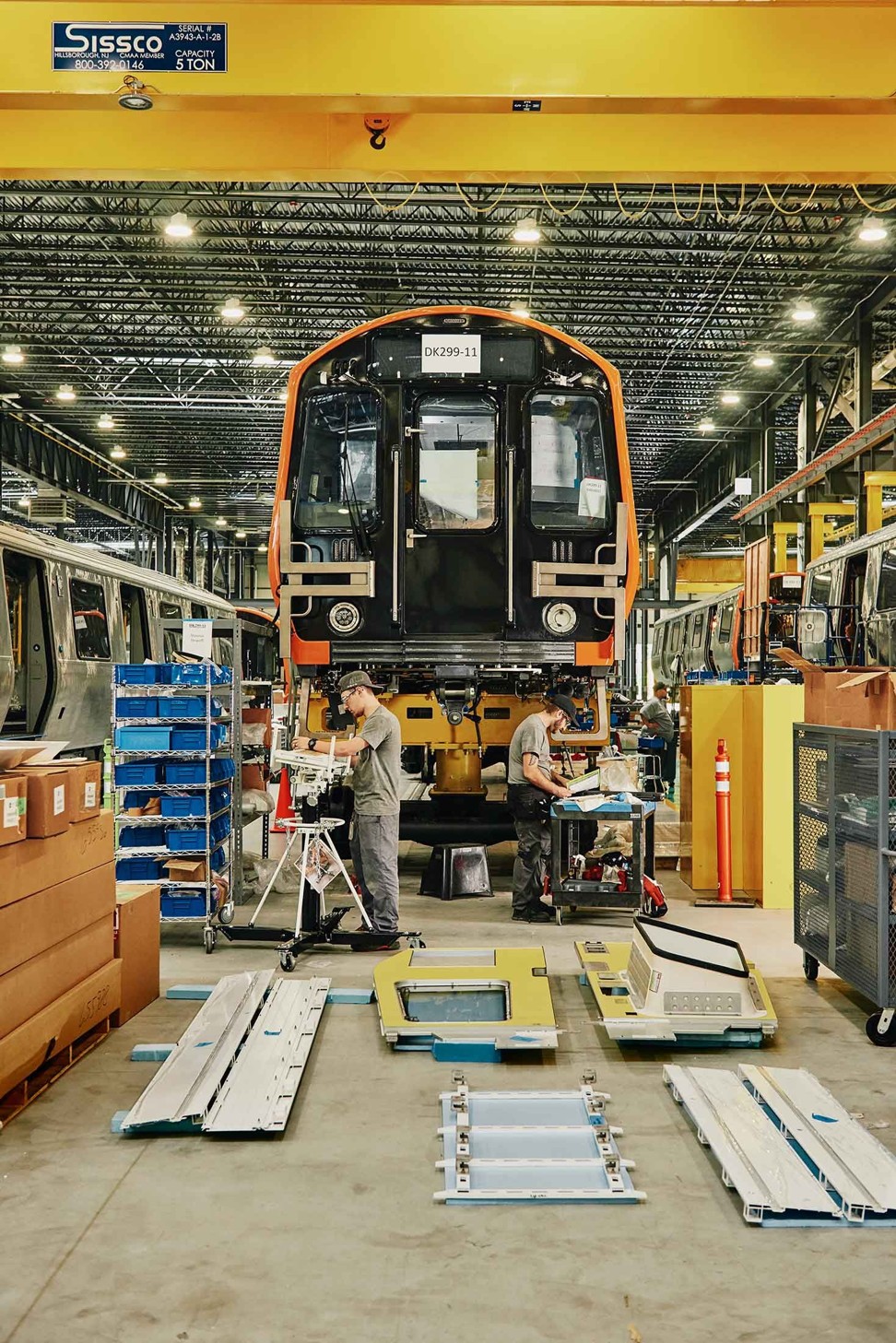

The concrete floors shine in the new US$100 million factory on Chicago’s far South Side. Towering shelves painted in blue, yellow and red are mostly empty. The quiet is eerie, punctuated only by a forklift’s occasional beep.

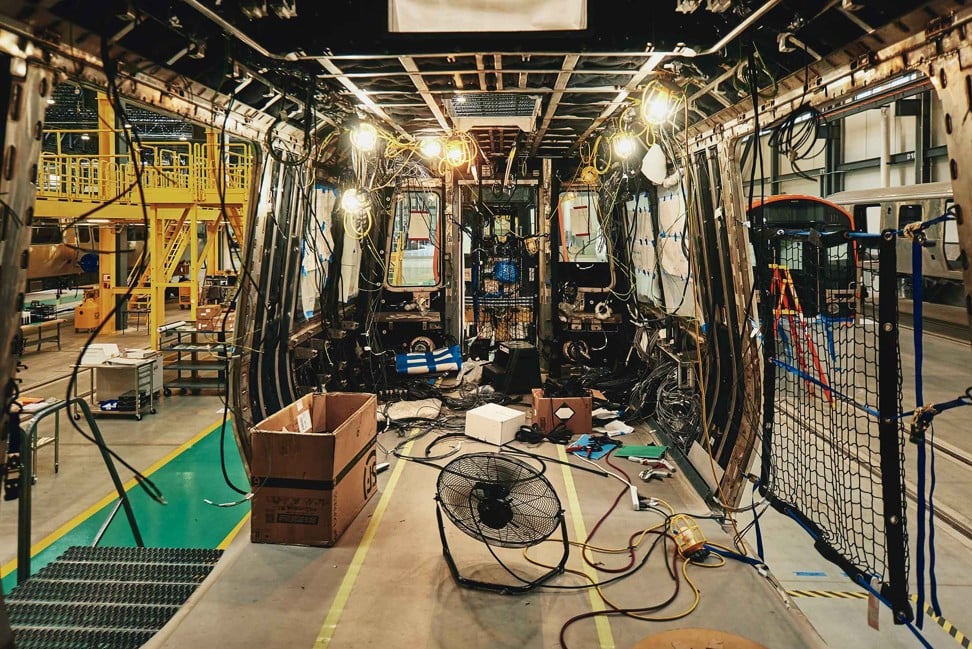

On a bank of two-metre-high platforms rest the steel shells of five 15-metre-long passenger carriages destined for the Chicago Transit Authority. Inside them, clutches of workers trace multicoloured bundles of wire.

Outside, others in safety helmets and glasses attach heating, ventilation and air-conditioning equipment to the undercarriages. All work for the Chicago subsidiary of CRRC Corporation. And what they are doing scares the hell out of some American manufacturers and Washington politicians.

CRRC is the world’s largest maker of freight wagons and passenger carriages. Over the past decade, the Chinese state-owned company has gone from country to country underbidding rivals and taking business from giants such as Alstom, Bombardier, Siemens and Hyundai Rotem. When Munich-headquartered Siemens and Paris-based Alstom tried to merge two years ago, before being blocked by European Union regulators this February, the companies cited the CRRC juggernaut as one rationale.

The Chinese company effectively wiped out Australia’s home-grown railway carriage industry in less than a decade. Early last year, CRRC declared in a since-deleted tweet, “So far, 83% of all rail products in the world are operated by #CRRC or are CRRC ones. How long will it take for us conquering the remaining 17%?”

Since 2014, CRRC has won US$2.6 billion in contracts to supply subway carriages to transit authorities in Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles and Philadelphia. The Chicago factory and another in Springfield, Massachusetts, along with a parts-making facility in Los Angeles, collectively employ about 365 workers – including more than 150 union members earning as much as US$32 an hour – and plan to add dozens more.

In Chicago, production manager Brian Vasquez strolls the floor pointing out empty areas where his facility intends to expand into, among other things, double-decker commuter carriages. “It kind of looks like overkill,” Vasquez says, “but CRRC is preparing for the future.”

So much of the conversation about China is what we think they might be up to but so far have no evidence forBruce Dickson, professor of political science, George Washington University

That future is uncertain, in no small measure because of the dysfunctional relationship between the United States and China. This is how fraught things are: in a Congress where it’s almost impossible to get anything significant done, four US companies in the freight-wagon business have persuaded the House of Representatives and the Senate to pass legislation that would withhold federal funds for any municipal project using CRRC wagons.

Echoing the Trump administration’s charges against Chinese telecoms giants Huawei Technologies and ZTE Corp, CRRC’s antagonists argue that the train maker will use its advantages as a subsidised company to dominate not only the US passenger-carriage industry but also, eventually, the larger freight-wagon business. They say, too, that China will use CRRC coaches for espionage, an economic and military security concern.

Both Republican and Democratic lawmakers have embraced these arguments, and if you’d like Washington to help you kneecap a Chinese rival, now is a good time. FBI director Christopher Wray told a congressional hearing in July that “there is no country that poses a more severe counter-intelligence threat to this country right now than China”, accusing it of trying “to steal their way up the economic ladder at our expense”.

Lobbyist Erik Olson, of the Rail Security Alliance, which represents the four American freight-wagon companies, says it’s perilous to give CRRC any benefit of the doubt. “You can’t mitigate against the threat,” he says. “You have to choose risk avoidance: don’t buy the train in the first place.”

In Chicago, on a sunny March day in 2017, then-mayor Rahm Emanuel plunged a shiny silver shovel into a mound of dirt 30km south of downtown. He, along with a few other local politicians and CRRC officials, was breaking ground for the factory. It was going up in the blue-collar Hegewisch neighbourhood on an 18-hectare site near a Ford Motor plant, a United Auto Workers hall and a couple of beer-and-shot joints.

The project promised the community 170 jobs and the renewal of an industry that had disappeared when the last carriage shop closed in the early 1980s. “Four years from now, Chicagoans like myself will be commuting on a railcar made in Chicago by Chicagoans,” Emanuel said. That the plant would be built by a company based in Beijing didn’t seem to matter.

No US companies make passenger carriages. That is partly because Americans don’t travel on trains nearly as much as they do in automobiles. Most of the companies that make carriages for the US hail from countries where train travel is more common: Alstom (France), Hyundai Rotem (South Korea), Kawasaki (Japan) and Siemens (Germany).

And CRRC. The company’s roots can be traced back to 1881, when Xugezhuang Machinery Works built China’s first steam locomotive, nicknamed “Rocket of China”. Today, CRRC is effectively a subsidiary of the People’s Republic, with more than 180,000 employees working at over 40 subsidiaries around the world.

The current version of the company was formed by the merger of two huge makers of rail gear in 2015, the same year Beijing issued its Made in China 2025 policy. That initiative listed 10 industries in which China seeks to become a global power. No 5 is advanced rail equipment.

The mainland has tried to mute its ambitious tone as the trade war has heated up, but a recent report from the Berlin-based Mercator Institute for China Studies said the country “has not at all abandoned its economic – and strategic – goal of catching up with Western industrialised countries and gaining a competitive edge in high-tech and emerging technologies”.

CRRC posted a profit of US$1.5 billion last year on revenue of US$33.1 billion. It landed its first US contract in Boston five years ago and secured orders to build carriages for Chicago and Los Angeles not long after.

In Boston, its US$567 million bid to supply 284 subway carriages beat out the closest rival, Hyundai Rotem, by US$150 million. In Chicago, its US$1.3 billion bid for 846 coaches was US$226 million less than the offer from Canada’s Bombardier.

Dave Smolensky, a spokesman for CRRC’s plant in Chicago, says Bombardier originally bid lower in a previous round in which CRRC didn’t participate, then raised its bid after a competitor dropped out. Bombardier “thought they were going to be the sole bidder”, he says. “It’s a perfect example of what happens when you lose competition.”

A Bombardier spokeswoman calls this a misrepresentation, saying the requirements changed for the second bid. “We submitted a highly competitive proposal designed to win.”

CRRC’s critics say the Chicago contract was the almost inevitable result of a state-owned company undercutting rivals with financial help from back home and dangling baubles, such as new factories, before local politicians. According to the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, created by Congress in 2000, CRRC received US$194 million in subsidies in 2014 and an additional US$268.7 million the next year.

However, a recent study by the Congressional Research Service, an organ of the US Congress, concluded that allegations of unfair undercutting have “not been proven”, given that the company failed to win contracts in Atlanta and New York.

It wasn’t CRRC’s initial success making US passenger carriages that provoked the company’s antagonists, but a flop in freight wagons. The freight-wagon-manufacturing business is decidedly different from that of its passenger cousin. For one, it’s a viable domestic industry – consulting firm Oxford Economics estimates that it accounts for about US$5 billion in annual revenue and 65,000 US jobs.

While passenger carriages, with their interior seating, air conditioning and other comfort features, can cost more than US$1 million apiece, a freight wagon rarely costs more than US$150,000. But freight is a more consistent business over time, because while it’s linked to broad economic cycles, it relies less on customers’ episodic decisions to upgrade their fleets.

Municipalities that use federal funds to buy passenger carriages must also follow Buy American laws dating to the Great Depression that require manufacturers to use minimum numbers of parts from US-based suppliers. No such rules apply to freight.

CRRC’s freight-wagon ambitions in the US first became evident in 2014, when it joined with a Wilmington, North Carolina, rail technology company called Vertex and a Chinese private equity firm to form Vertex Railcar Corp. Vertex was to build a variety of wagons in Wilmington, creating more than 1,000 jobs.

The company apparently sold some wagons, but legal and other troubles forced it out of business last year. CRRC’s involvement nevertheless caught the attention of Amsted Rail, a Chicago-based maker of freight-wagon parts.

Olson says Amsted was concerned about CRRC partly because Chinese state-owned enterprises tend to rely heavily on Chinese suppliers. Amsted had noticed with alarm that after CRRC’s two predecessor companies entered the Australian railway-carriage industry in 2016, they took over.

The largest Australian carriage maker, Bradken, had a 40 per cent market share in 2008; by 2017, it had exited the freight-wagon and passenger-carriage markets and CRRC claimed virtually all of both. Amsted sought help from Olson, a former congressional staffer who had joined Venn Strategies, a Washington lobbying firm.

In May 2016, Olson helped form the Rail Security Alliance with Amsted and three other US rail-equipment makers: American Railcar Industries, the Greenbrier Companies and Trinity Industries.

By September, more than 50 congressional Republicans and Democrats had signed letters to the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US (CFIUS), urging it to review CRRC’s role in the Vertex joint venture. The lawmakers argued that the Chinese company was likely to shift purchasing to China, leaving Americans with nothing more than assembly work. They also raised concerns about cybersecurity.

CFIUS never acted on Vertex. But the US suppliers started lobbying for legislation that would ban municipalities from accepting federal funding for contracts with CRRC. Key congressional supporters included Senator John Cornyn, a Texas Republican, and others with rail interests in their states or districts.

Last year, the ban on federal money made it into a government funding bill but was stripped out before the legislation reached US President Donald Trump’s desk. The companies have continued pushing for the ban, amplifying concerns that CRRC trains pose a cybersecurity threat.

The ground in Washington was fertile for such talk. As the Rail Security Alliance cranked up its spy-train campaign, the Pentagon was banning the sale of Huawei and ZTE phones on American military bases, the US Army was stripping its bases of surveillance cameras made by Chinese state-owned Hangzhou Hikvision Digital Technology, and Beijing was denying reports that it had bugged the headquarters it built in the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa, for the 55-nation African Union.

On Washington’s Capitol Hill, the alliance circulated a glossy, 15-page pamphlet, written by retired US Army Brigadier General John Adams, highlighting potential economic and cybersecurity threats posed by CRRC. It raised the possibilities of China secretly monitoring military rail movements and facilitating toxic chemical spills.

“I know they have the capability because we have the capability. We just don’t do it,” Adams says. “And I do believe, based on their behaviour, that they have the intent.”

It was in this atmosphere that CRRC emerged late last year as a possible bidder on a contract to supply carriages to the Washington subway system. Security hawks immediately started floating the prospect of China using secretly implanted devices to watch and listen to policymakers as they rode the rails near the Pentagon and Capitol. Congressional hearings followed.

The legislation that fell short last year started moving again, and the Rail Security Alliance picked up support from the Alliance for American Manufacturing, the Railway Supply Institute and other advocacy groups.

There have been no reports of CRRC trains being used to snoop. “It’s a conspiracy theory right up there with Bigfoot,” says Smolensky. “Once a railcar is delivered to the transit authority, they have full operational control. The manufacturer does not have access to the railcar.”

Before this plant was here, this was a big, empty lot,” he says. “CRRC is offering Springfield a lifelineJohn Scavotto Jnr, business manager, Sheet Metal Workers Local 63

Robert Puentes, president of the Eno Centre for Transportation, a non-profit think tank, says that transit authorities carry out regular quality inspections and that it’s “ludicrous” to think a manufacturer could sneak surveillance devices into trains. “If the federal government really wanted to be helpful,” he says, “instead of blocking CRRC, they could give people more money to do better inspections.”

It’s not always that simple. The inspector general of Washington’s transit authority found that third-party contractors and vendors could unwittingly make the subway system vulnerable to cyberattacks. In theory, as CRRC helps to maintain the carriages it built, the company could create back doors for intrusion via software updates. Those “could be turned on and off as needed”, Adams says.

CRRC’s adversaries have seized on a federal indictment charging a Chinese software engineer at an unnamed Chicago locomotive manufacturer with stealing proprietary information and taking it to China. Although CRRC wasn’t implicated, the alleged theft “makes clear that the US rail market is also becoming a target” of China, says a recent report by consulting firm Veretus Group.

Freight wagons pose a somewhat different vulnerability from passenger carriages because they ferry economically valuable items such as timber and oil, and also because they are crucial to military mobilisations. “Rail networks are particularly at risk because they are extensive, dispersed and complex,” says a recent report by management consulting firm Oliver Wyman. The industry is rolling out a nationwide web of Wi-fi, GPS and other technologies designed to smooth scheduling and prevent crashes; that, too, could be a target for bad actors, the report says.

“So much of the conversation about China is what we think they might be up to but so far have no evidence for,” says Bruce Dickson, a professor of political science at George Washington University. “You either are suspicious that they might do something and deprive yourself of a high-quality, low-cost railcar, or you can say there’s no evidence and then look like a dupe.”

John Scavotto Jnr, business manager of Sheet Metal Workers Local 63, which represents some workers at CRRC’s Springfield plant, says it’s frustrating that CRRC hasn’t received more credit for paying Americans good union wages. “Before this plant was here, this was a big, empty lot,” he says. “CRRC is offering Springfield a lifeline. It’s a place where you know you’re going to go every day and walk out in 20 years with a pension. There’s security.”

Scavotto says he gets “wound up” at talk of CRRC building spy trains, because his members worry it could cost them their jobs. “Are we really saying to ourselves that the Chinese are smarter than us?” he says. “If it isn’t CRRC, who’s it going to be? There is no American railcar manufacturer. We let the Germans come in here, South Korea, France – they’re all foreigners.”

CRRC’s critics say the Chicago and Springfield factories employ far fewer workers than would be required to manufacture entire carriages – hence the relative quiet in the two facilities. The company ships prefabricated train shells to the US, where workers fit them out with necessary equipment. Officials at the two plants say they satisfy Buy American rules, which require 70 per cent US content. The recent Congressional Research Service study concurs.

“Do we have an advantage in building shells in China? Absolutely,” says Springfield facility director Vince Conti, a 30-year carriage industry veteran who previously worked for Bombardier in China, India and elsewhere. “It feels like we’re being targeted because we’re a Chinese company.”

Well, yes. The question is whether the concerns surrounding CRRC are legitimate. The Rail Security Alliance has spent US$2 million on lobbying, most of it going to Olson’s firm, Venn Strategies, according to OpenSecrets.org. The two US CRRC factories, which have retained lobbyists only in the past year or so, have spent at least US$160,000.

The Massachusetts factory recently launched a website that seeks to counter anti-CRRC claims, boasting that the plant uses parts sourced from New Jersey, South Carolina, Wisconsin and other US states. The site also links to Wall Street Journal and Boston Globe editorials casting trains as no more of a spying threat than ubiquitous Chinese-made smartphones.

None of this is likely to stave off the legislation, which this time is part of a defence spending bill. Assuming it becomes law, CRRC would be allowed to fulfil its current contracts, all of which involve federal funds except the one with Boston. Any transit authorities that sign a contract with CRRC in the future would have to do without federal dollars.

That could change the calculations considerably. CRRC’s spokeswoman in Springfield, Lydia Rivera, says the legislation would eventually force the factory to close. Smolensky won’t go that far. He says CRRC will continue to educate policymakers about the “unintended consequences” of the legislation: lost jobs and higher prices for carriages.

Additional reporting by Chunying Zhang

Text: Bloomberg Businessweek