Fighter pilot turned author Mohammed Hanif on mining his homeland of Pakistan for humour

The 55-year-old writer of A Case of Exploding Mangoes and his latest, Red Birds, reveals how he’d happily bargain away his career for a life of normality

Hanif, who lives in Karachi, had been invited last year to give the 2019 PEN Hong Kong Literature & Human Rights lecture at HKU. PEN, which stood for Poets, Essayists, Novelists but now embraces all literary forms in its role as human-rights watchdog, planned for Hanif to take part in an evening with local writers titled “We Still Laugh: Humour as a Literary Relief Valve”. By lunchtime on his first day in Hong Kong, however, student outrage had been ignited, tear gas was seeping through Central and no one was laughing.

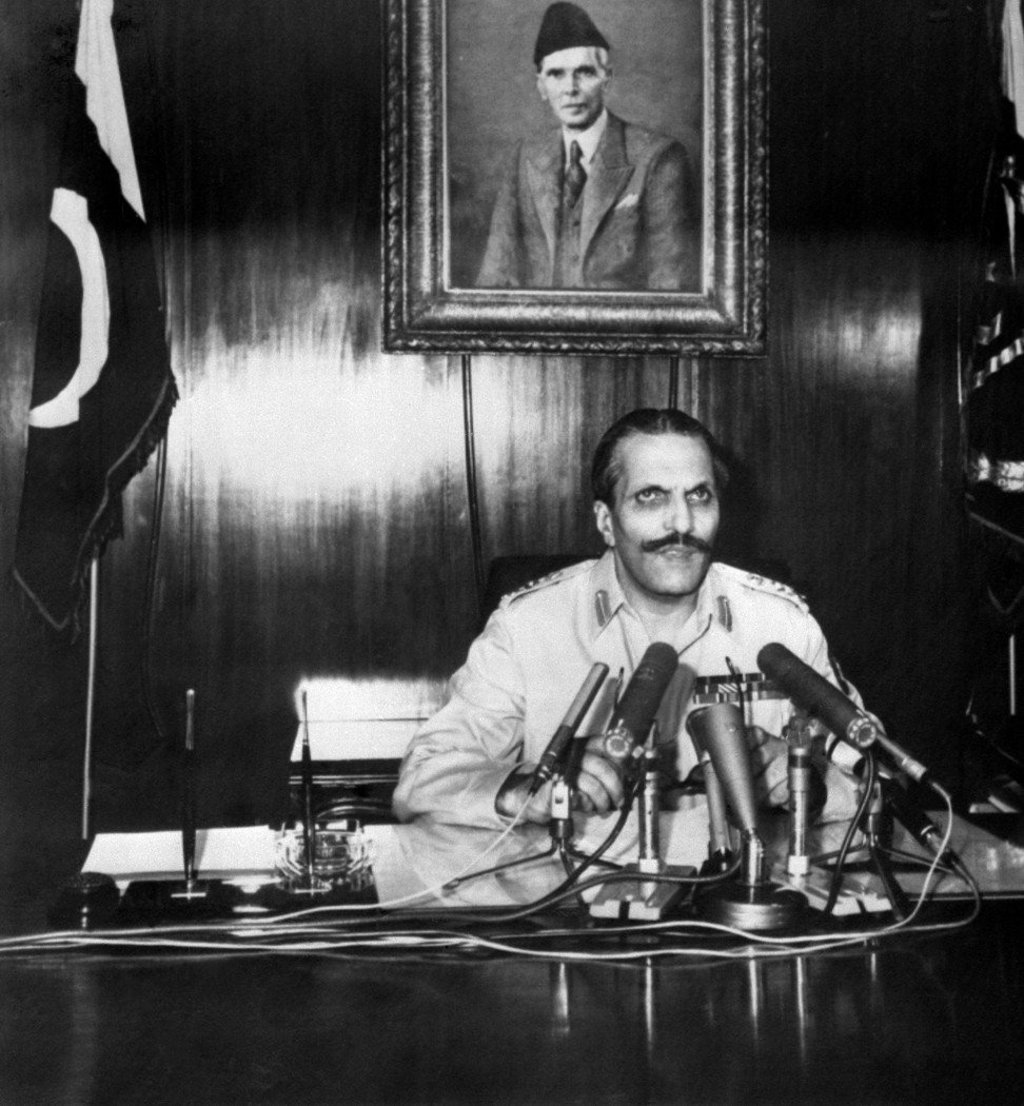

Anyone familiar with Hanif’s work, which can be simultaneously amusing and appalling, will appreciate this collision between writer and unpleasant reality. His 2008 debut novel, A Case of Exploding Mangoes revolves around the 1988 crash of a plane carrying Pakistan’s president, General Zia-ul-Haq, in which at least 30 people died, including Zia and the American ambassador. It evoked comparisons to Joseph Heller’s classic 1961 war-satire, Catch-22.

In 2011, his second work of fiction, Our Lady of Alice Bhatti, assessed Pakistan’s Islamic patriarchy through the eyes of a female Christian nurse in Karachi. Acid attacks were among the (many) sufferings inflicted upon its women, and the book was described in The New York Times as “a deft, evil little novel of comic genius”. Hanif was now in the classified territory of a satirist.

His third novel, Red Birds, was published by Bloomsbury in 2018. It was the first not to be set in Pakistan: the action takes place in a war-ravaged desert “with distant sounds of metal cracking in the sky”. Humour is present, but mining for it amid the bitter philosophy (“In the process of trying to eliminate the other, you become the other”) feels like harder work, for both author and reader. You wince more than grin. You think: a blitheness of spirit has been lost.