Korean-Canadian Jim Paek helped blaze a trail in the NHL for new talent with Asian heritage, including Jett Woo, Matt Dumba and Kailer Yamamoto. With the league keen to build a fan base in Asia, the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics will be the sport’s moment in the spotlight.

The NHL estimates there are at least 20 prospects of Asian descent in its various feeder leagues, which is almost as many players of Asian heritage it has seen in its entire century-plus history.

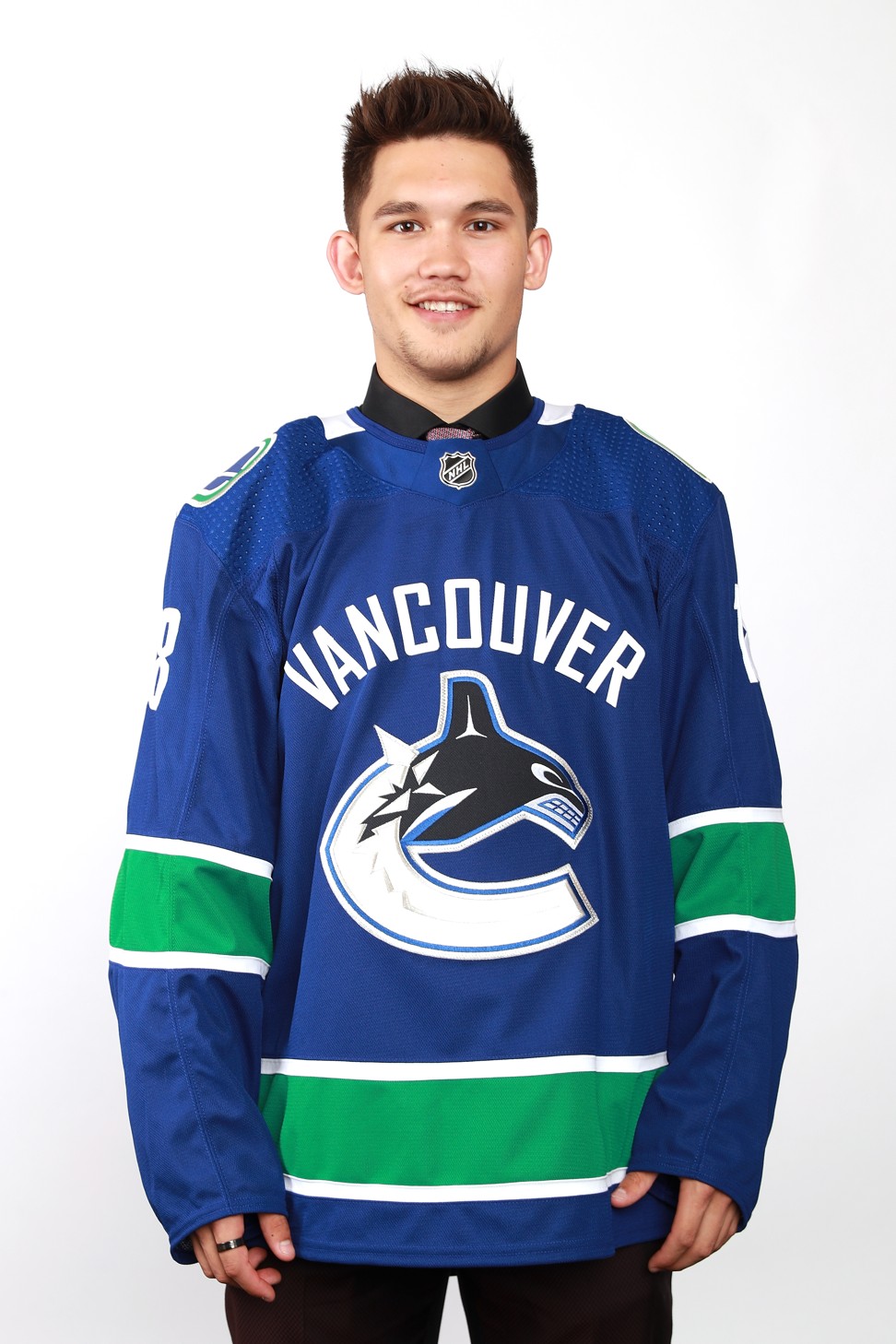

“It’s pretty amazing,” says Woo, who was named after Chinese action film star Jet Li. “The game has changed so much over time and not just with how it is being played, but who is getting the chance to play.”

Things have come a long way since Jim Paek’s first NHL shift in October 1990. Then a spry, 23-year-old defenceman, Paek had been called up from the Muskegon Lumberjacks of the International Hockey League to join the now-legendary Pittsburgh Penguins roster led by French-Canadian superstar Mario Lemieux and rounded out with future Hall of Famers Jaromír Jágr, Mark Recchi, Paul Coffey and Bryan Trottier. Paek recalls lining up for an offensive zone face-off: “My knees were shaking as they were about to drop the puck. It wasn’t until a few games down the road where I was like, ‘I made it’. And it hits you like a ton of bricks. All the blood, sweat and tears, and here I am.”

Paek, who made his name as a stay-at-home defenceman, came into a league then made up almost entirely of Caucasian players of largely European ancestry. And while Paek is not the first player of Asian heritage to lace up his skates in the NHL – that honour goes to Larry Kwong, whose father was from China and who played just one shift for the New York Rangers, in 1948 – his career was the first to take hockey’s colour barrier hard against the boards.

Born in Seoul, in 1967, Paek and his family moved to Toronto when he was a year old, and he took to hockey like any other Canadian kid: Canadians account for more than 40 per cent of the league’s 713 or so players today, and have made up the vast majority of players in the NHL since it was founded, in 1917.

Canadian hockey pundit Don Cherry fired over remarks about immigrants

“I was truly blessed with my parents, who supported me and what I wanted to do, not following the stereotypical Asian thing where you have to be a doctor or lawyer,” says Paek, who is now the head coach of the South Korean men’s ice hockey team. (His siblings, however, are a doctor and a lawyer.)

In Paek’s first season, the Penguins won the Stanley Cup for the first time, in 1991, then lifted the trophy again the following year, making Paek not only the first Korean-born player to hoist the prestigious award – his jersey hangs in the Hockey Hall of Fame to commemorate this – but also the first to do it twice.

Paek played in 217 NHL games before hanging up his gloves in 2003 – by then, he was playing for the Nottingham Panthers of the British Elite Ice Hockey League – and moving into coaching. Over his 13-year NHL career, he encountered bigotry both on and off the ice, but insists that for the most part the game nurtured inclusivity.

“For sure you will have [bigotry], and you will have that anywhere,” Paek says, but any racist name-calling “was always water off a duck’s back with me”.

Growing up in multicultural, immigrant-friendly Toronto didn’t hurt. “I remember having players on my team who were Italian, or Indian, or Scottish, English; there were kids from everywhere,” he says.

Underwater hockey to make waves at Southeast Asian Games

During the 1960s, Canada wiped the last vestiges of institutionalised racism from federal policies and, by 1971, the majority of immigrants to the country were of non-European ancestry, which is still true today. In 1988, the government passed the Canadian Multiculturalism Act, enshrining respect for various languages, cultures, customs and religions. While far from perfect – outside the cities, non-white discrimination isn’t hard to find – a 2013 study by Swedish economists found Canada had some of the lowest levels of racism of 80 countries surveyed.

“The hockey community, for the most part, is very supportive,” Paek says. “You’re all there early in the morning, driving your kids to the same practice in the freezing cold. So you were all raised by strong families with strong values.”

According to NHL figures, only 23 players of Asian heritage have played in the league, appearing in more than 5,000 games and winning close to 2,000 points. Following in Paek’s footsteps, in 1994, was Paul Kariya, whose Japanese-Canadian father was born in a World War II internment camp in British Columbia. Kariya’s statistics were remarkable given his relatively diminutive size (he was 178cm tall and just under 84kg at a time when being 182cm and 90kg was a minimum requirement). When he retired, in 2011, Kariya had amassed 989 points in as many games.

While the list of NHL players with Asian heritage has remained relatively short, University of British Columbia history professor Henry Yu says this under-representation is more a matter of geographical immigration trends than discrimination.

“In a lot of urban places, like Vancouver, rink time is expensive and hard to come by. [It’s] the same in Toronto. So places outside the cities [have] tended to dominate. You could say that immigration in Canada is a very urban phenomenon, while hockey has always been traditionally a rural game,” he says. “It wasn’t that the NHL was trying to exclude Asians. There just used to be one single dominant path, which was the junior route in Canada, and the college route in the United States.”

Kariya, born and raised in north Vancouver, was overlooked by junior scouts in Canada owing to his small stature and instead moved to the US and played two seasons at the University of Maine (1992-94), where he scored 124 points in 51 games. The powers that be quickly took notice.

“So you have people like Paul Kariya, who probably wasn’t going to be a star in the [major juniors’ Western Hockey League], but becoming a college star in the US started to open up all those different routes to the diversification of the NHL,” Yu says. “And it’s not a race thing: it opened things up for smaller players, and European players as well.”

Later that month, the Calgary Flames’ head coach, Bill Peters, resigned after admitting to using a racial slur in relation to one of his former players, Nigerian-born Akim Aliu. In December, The Wall Street Journal ran an article headlined “Diversify or Die: The National Hockey League has a Demography Problem”. Earlier in March, The Guardian had run a similar piece, titled “Hockey has long been about white machismo. Can the NHL change that?”

While such clickbait headlines tend to dominate news cycles, many are quick to forget the leaps and bounds made by leagues such as the NHL in cultural expansion.

In 2008, long before excluding Cherry, CBC introduced a Punjabi version of Hockey Night in Canada. It shot to fame in 2016 after announcer Harnarayan Singh famously yelled “Bonino! Bonino! Boninoooo!” in response to a crucial goal by Penguins forward Nick Bonino, making instant international celebrities of the broadcast team. The show was launched the same year the NHL started broadcasting games in Mandarin.

Marketing firm Scarborough Research estimates there are more than 13 million non-white NHL fans in the US alone, which accounts for 22 per cent of the sport’s total following. The past decade has seen a 13 per cent increase in black fans, a 51 per cent increase in Hispanic or Latino fans and a 55 per cent increase in Asian fans, according to the study.

It is telling that Winnipeg’s Woo is being drafted by a team from Vancouver, where almost half the city’s population are of Asian descent. (To celebrate this heritage and mark the Lunar New Year, before their January 18 game against the San Jose Sharks, Canucks’ players will host a lion dance and, for the third year in a row, wear special red warm-up jerseys.)

This growing ethnic diversity is not limited to Canadian cities. In San Jose, California, for example, people with an Asian background make up nearly 15 per cent of the Sharks’ fan base and nearly 20 per cent of patrons at the club’s community rinks.

The NHL’s executive vice-president for social impact, growth initiatives and legislative affairs, Kimberly Davis, who is African-American, says the league is becoming a “mosaic” when it comes to the names on the backs of the jerseys.

Since the 1989-90 season, some 167 “players of colour” from a wide range of ethnicities have played at least one shift in the NHL, Davis says. This includes players from Mexico, the Caribbean, Lebanon, Syria, Japan, Korea, Thailand and China, as well as black Canadians, African-Americans and players from indigenous communities across North America.

Players of African heritage have already become household names, including the Ottawa Senators’ Anthony Duclair, the Columbus Blue Jackets’ Seth Jones, the San Jose Sharks’ Evander Kane and New Jersey Devils’ P.K. Subban and Wayne Simmonds.

Having talented players of colour in the game, be it Jett Woo or Evander Kane or Alec Martinez – whose grandfather is Spanish-American – is beneficial to hockey [...] But it’s important to stress that these players have gotten to where they are based on their talentWilliam Douglas, writer for NHL.com, founder, The Color of Hockey

NHL.com writer William Douglas, founder of the popular blog The Color of Hockey, says black players have helped expand the league’s fan base. Devante Smith-Pelly (currently with Beijing-based Kunlun Red Star, which plays in Russia’s Kontinental Hockey League) became a “folk hero” for the Washington Capitals during the 2018 Stanley Cup play-offs by scoring key goals and helping his team lift the cup.

“African-Americans in Washington and beyond paid attention to the final because of Smith-Pelly’s run,” Douglas says. “Having talented players of colour in the game, be it Jett Woo or Evander Kane or Alec Martinez – whose grandfather is Spanish-American – is beneficial to hockey in terms of connecting with new fans, and perhaps inspiring them to take up the game. But it’s important to stress that these players have gotten to where they are based on their talent.”

Ice hockey will truly connect with Asia in 2022, when Beijing hosts the 24th Winter Olympics. It will be hoping to repeat the success of the Beijing Summer Olympics, in 2008, when China hauled in 100 medals, coming second in the overall standings behind the US.

China looks to conquer ice hockey after the boom in basketball

The Chinese government is pouring money into infrastructure for winter sports across the country, with an emphasis on skiing, snowboarding and, of course, hockey. According to the Beijing Review news magazine, China had 21 indoor ice rinks in 2003, and 188 by 2017,with industry experts estimating the country has a market for a potential 3,000.

While China’s chances of getting onto hockey’s medal podium are slim, the Olympics will showcase the sport to the country’s 1.3 billion people. One Chinese-Canadian player who could be playing for China at the Olympics is 26-year-old Zachary Yuen, born in Vancouver, and now playing for a Beijing-based team in Russia’s second division. While Yuen says playing for his motherland would be an honour, he understands the high expectations that accompany pulling on a red jersey for a country that demands performance and results.

“You don’t introduce a new sport to a country overnight,” Bettman told the Post from Shenzhen in 2018. “You have to do it over the long term and that’s what we’re committed to.”

The NHL is also on Weibo, China’s state-controlled answer to Facebook and Twitter, and now has more than a million followers.

One of the NHL’s feel-good stories of the season features an up-and-coming player of Asian heritage, 21-year-old Kailer Yamamoto, whose father is half-Japanese and half-Hawaiian. The speedy winger from Spokane, Washington, has played sparingly for the Edmonton Oilers since 2017 but since being called up on New Year’s Eve to face the New York Rangers, he seems to be making his case for a permanent spot on the Oilers roster as a top-six forward, as superstars Connor McDavid and Leon Draisaitl lead the team into what they hope will be a deep play-off run after years of disappointment.

Yamamoto, whose grandfather was in a Japanese internment camp in the US during WWII, says knowing about his heritage and the struggles of his lineage has made him more thankful for his upbringing. His older brother, Keanu, who played alongside him for the WHL’s Spokane Chiefs, is now playing for McGill University’s varsity team in Montreal.

“It was unbelievable, being able to stay at my house and play my first three years with my brother, it was kind of a dream come true. If you can grow the game in terms of various ethnicities, it’s great, and if I can be one of those guys, it would be awesome,” Yamamoto says.

Spokane is one of several up-and-coming hockey hotbeds in what were previously considered unlikely locales, as the sport finds its way into non-traditional markets, on and off the continent. The city of nearly 220,000 people will have a local team to support from the 2021-22 season when nearby Seattle becomes the 32nd team to enter the NHL. Yamamoto says his hometown is becoming a solid breeding ground for top-notch talent.

On the other side of the experience spectrum is hard-nosed Minnesota Wild defenceman Mathew Dumba (mother Filipino, father German-Romanian). The 25-year-old was born in the Canadian prairie province of Saskatchewan, and moved to the Alberta oil town of Calgary – another hockey hotbed – when he was six. It was there that Dumba first laced up the skates, and where he encountered racism.

“I had to battle that when I was younger,” says the NHL veteran of seven seasons. “Little kids are mean … the slurs and stuff like that. And so I just want to help eliminate that and bring diversity to this game.”

Covered in tattoos, Dumba looks nothing like the stereotypical white hockey player, but he’s not only OK with this, he’s actively embracing being a role model for children who may have thought hockey wasn’t for them. “I definitely think it’s cool because […] this game is for everyone, and I guess it is no longer what you would call a ‘white’ sport,” he says.

Paek, saddled with the daunting task of trying to coach South Korea to the 2022 Olympics to compete against hosts China and perennial heavyweights Canada and Sweden, says he was always a hockey player who happened to be Asian – not the other way around. He recalls a common retort to any bigoted comment faced during his long and multi-continental career: “Judge me on my hockey skill. It doesn’t matter where I come from.”