The Portuguese colony’s potential as a hub for transpacific flights came to light in the 1930s – as did a mystery bid to buy it outright

In the 1930s, Western newspapers were in the habit of portraying Macau as a haven of pirates, scoundrels and ne’er-do-wells, gambling the days away and smoking opium by night. Bestselling French writer of the interwar years Maurice Dekobra had a hit with his 1938 novel, Macao, enfer du jeu (Macao, Gambling Hell), which became an equally sensationalist film starring Erich von Stroheim, Parisian starlet of the day Mireille Balin and the first Japanese actor to conquer both Hollywood and European cinema, Sessue Hayakawa.

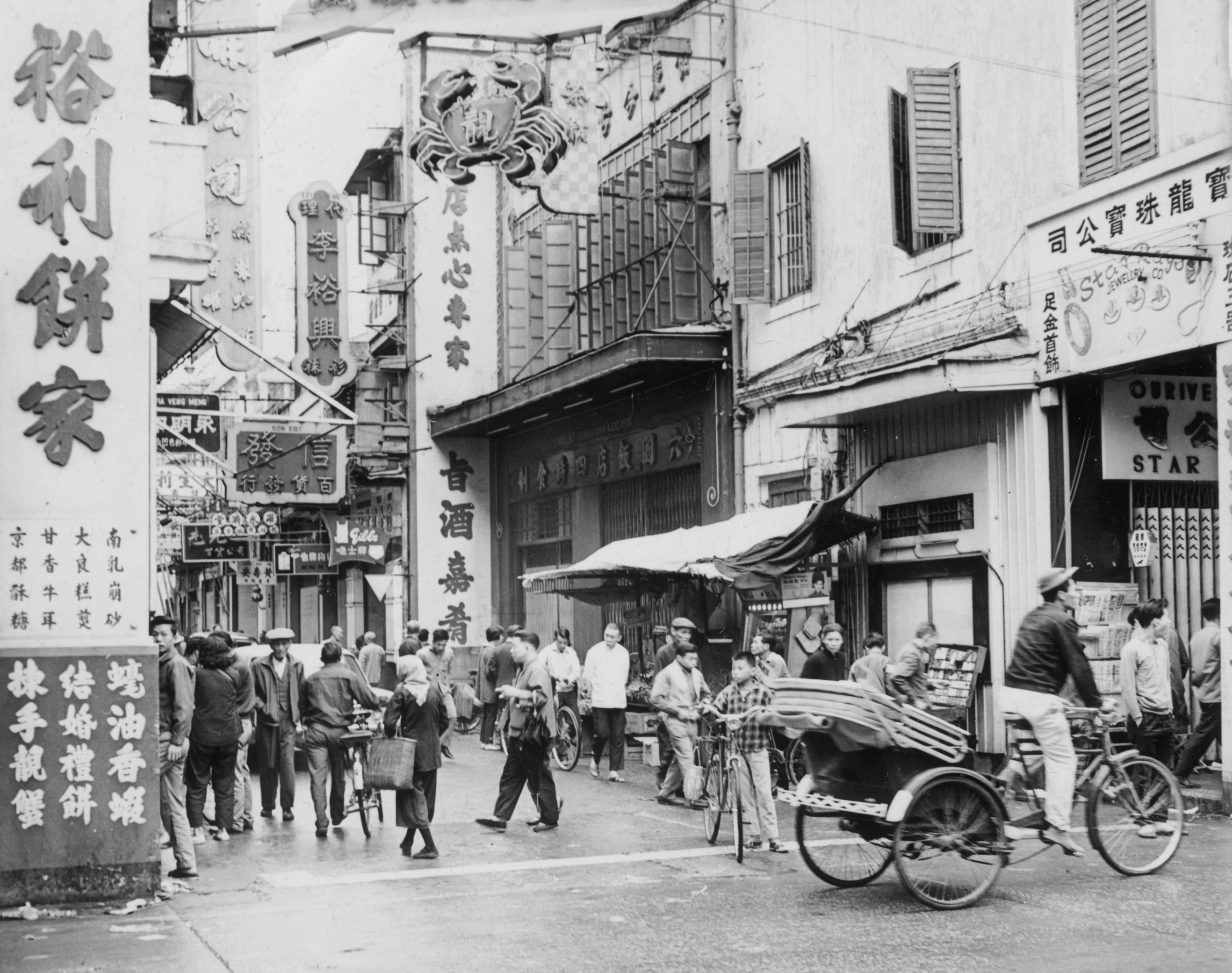

Lacking Peking’s bohemianism, Shanghai’s modernity or Hong Kong’s dynamism, Macau sat in the South China Sea, fanning itself in the heat, a decaying relic of the diminished Portuguese empire. The economy was hurting thanks to the British Royal Navy’s suppression of piracy and smuggling. Officially, it was good news, but not for Macau’s illicit cash flows, as offenders were arrested, beheaded or stayed away. And until-then reliable opium sales, a colonial government monopoly fuelling Lisbon’s treasury, were no longer yielding the same gains.

Previously, concessions for the game of fan-tan had brought in US$5,000 a day for the Portuguese administration – equivalent to US$100,000 a day, or US$35 million a year, in modern money – peanuts by the standards of today’s casino economy, but a large chunk of the Portuguese administration’s budget at the time. Worried that Macau would become a major drain on Portugal’s far-from-fecund coffers, Lisbon ordered officials in its southern China colony to dream up new revenue streams, which led to some serious head scratching in the enclave’s finance ministry.

Hong Kong had long eclipsed the Portuguese colony as a trading port. Traditional local industries of fishing, firecrackers and incense, as well as tea and tobacco processing, were all small scale. Options for new industries were also limited by a population of fewer than 200,000. But there was one avenue that didn’t require a large workforce or much local investment, and that would not only be lucrative for Macau and Lisbon, but also put the colony on the map as an important hub: transpacific flights.

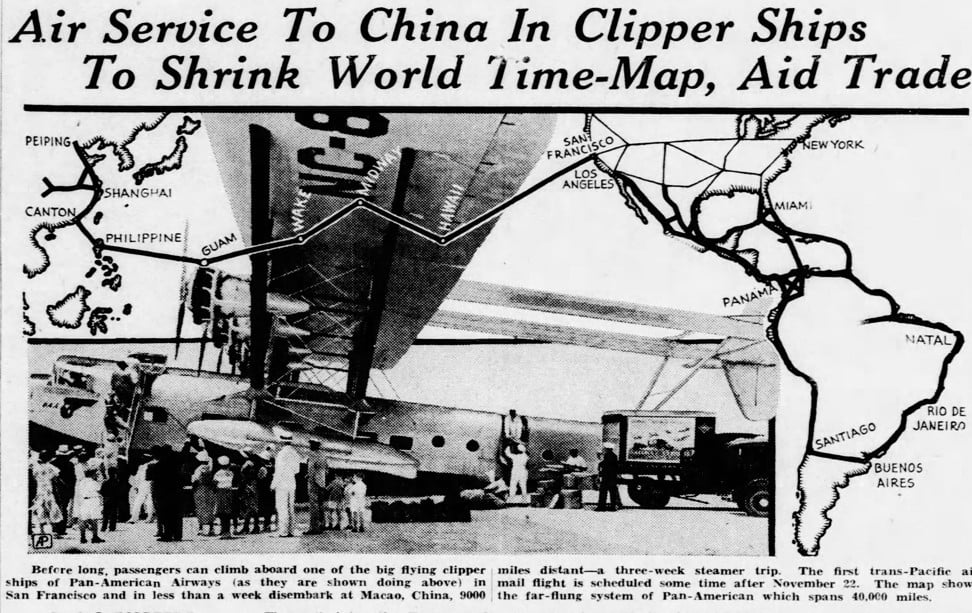

New York-based Pan American Airways was desperate to start a Pacific Clipper service from the United States west coast to south China, via its seaplane base on Oahu, Hawaii, and Manila, in the Philippines. The now-defunct aircraft company Glenn L. Martin, based in Baltimore, had built three Martin M-130 flying boats, which were named the Hawaii Clipper, the Philippines Clipper and the China Clipper after the 19th century sailing ships that raced across the Pacific taking tea to North America. Debuting in 1934, the M-130 was an all-metal aircraft with streamlined aerodynamics and engines powerful enough to fly passengers and cargo from the US to China. Crucially, the M-130 could take off and land on water.

The US Post Office (USPO) was also determined to initiate a transpacific crossing, from San Francisco via Hawaii, Guam and the Philippines to China. The post office was already working with Pan Am and had awarded the airline its airmail delivery contract, and the two had begun air services to New Zealand and Australia via American Samoa. They hoped postal services would grow into additional freight revenue streams, and then paying passengers.

Harllee Branch, who ran the transpacific project for the US Postmaster General, had publicly stated he would fly a letter from California to Hawaii and on to any Asian or Australasian destination in a day and a half, as opposed to the usual three weeks. And wherever the destination, the stamp would cost no more than US$1.

The Japanese were also interested. They intended to start an air service from Tokyo to Guangzhou via Shanghai. But it was 1934 and the emperor’s troops had recently annexed Manchuria, renaming it Manchukuo, with the young, deposed Chinese emperor Puyi as its puppet figurehead. Ferocious fighting between Japanese and Chinese soldiers in 1932, the so-called Shanghai incident, had rendered diplomatic relations between Nationalist China and Japan somewhere between cold and frozen.

The Nanjing government had refused landing rights to Japan Air Transport (JAT), the Japanese empire’s national airline, then – in order to not further antagonise Tokyo by favouring the US – also refused permission for Pan Am planes to refuel at Guangzhou.

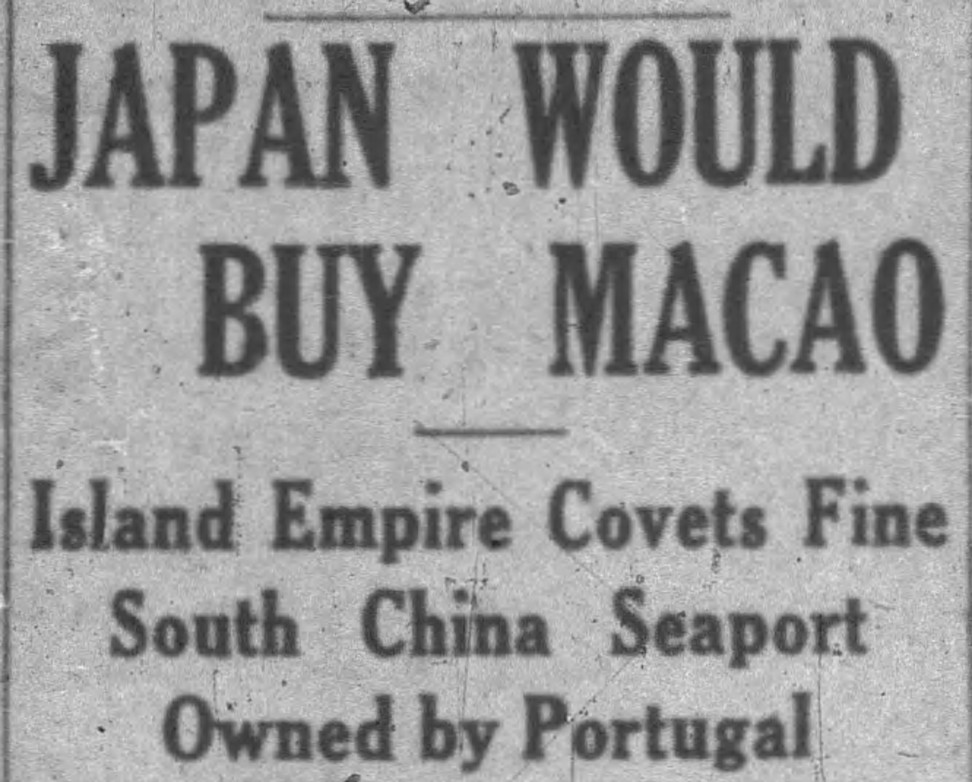

And so the USPO/Pan Am and JAT were looking closely at Macau – its geographical advantage, important in the days of the spice trade but mostly forgotten by 1934, had put the colony back on the map. The race was on to secure landing and refuelling sites for a true transpacific air service. It would lead to one of the wilder and most stubbornly persistent rumours of the era: that the Japanese had offered to buy the Portuguese territory outright.

In 1931, following Japan’s invasion of northeast China, JAT had established a subsidiary, Manchuria Aviation, to consolidate its new enclave. The airline offered services from Tokyo and Kobe to Japanese-occupied Korea, then to Shenyang, Harbin and the puppet state’s new capital at Changchun (which the Japanese called Hsinking). JAT also planned to develop a route from Tokyo to Japanese-occupied Taiwan.

Japan’s northern expansion in China had met little resistance, but possible encroachment into southern China was a different proposition. While Changchun was 2,600km from where the British were entrenched in Hong Kong, Guangzhou was just 130km away.

Tokyo knew Britain would never sell a crown colony, but it had good reason to believe down-at-heel Portugal might. The interwar period was tough not only for Macau, but also for the motherland. The First Portuguese Republic, founded in 1910, had collapsed in a military-led coup d’etat in 1926, after nine presidents and 44 prime ministers. So began the Ditadura Nacional (National Dictatorship) that, in 1933, became the so-called Estado Novo (New State), which lasted until the 1974 “carnation revolution” finally restored democracy to Portugal.

Throughout the First Republic and the subsequent military coup, the country’s financial situation was precarious. As a Portuguese colony, Macau’s glory days were long gone and now its heyday as a centre of piracy and smuggling seemed to be winding down.

It was broken by a Hong Kong stringer for London’s Daily Express newspaper, who claimed an official delegation was on its way from Tokyo to Lisbon to talk money, contracts and terms. Although no confirmation of the offer being made or received was forthcoming from either Tokyo or Lisbon, the rumour excited much interest.

British-inclined editorials universally judged it a bad idea and one that nakedly revealed Japan’s ambitions in southern China, which London then considered its own private sphere of influence. Following the invasion of Manchuria, where the League of Nations had appeared impotent to stop the Japanese army, and Shanghai in 1932, where a multi-nation response had been required to persuade Tokyo to back off, an attempt to purchase Macau was a step too far.

Pan Am and the USPO were similarly less than happy with the development. Their M-130 flying boats, which the press and public alike knew as the “China Clippers”, had passed the necessary tests to begin transpacific services. The USPO was reportedly preparing to issue a new postage stamp featuring the plane to celebrate the service’s launch.

JAT and its offshoot, Manchuria Aviation, were heavily subsidised by the Japanese government, which aided their plans with new airports, including Haneda Airport, in Tokyo, that had opened for flights to Taiwan, Korea and Changchun. The airlines used Japanese Nakajima AT-2s and German Fokker Super Universals. Nakajima then proceeded to purchased a production licence for America’s Douglas DC-2 and built half a dozen. The DC-2 had powerful engines and carried 14 sleeper passengers, but unlike the China Clippers, it was not a seaplane. The JAT DC-2 would need a runway.

But both airlines faced a problem. Pan Am could fly from San Francisco to Manila with stops at Hawaii, Midway, Wake Island and Guam. JAT could fly from Japan into northern China, then Taiwan. But that was it. Talks were ongoing with the British to eventually reach Hong Kong, but how to reach Guangzhou and the key market of southern China?

The Portuguese settled in Macau in 1557, but it didn’t become a formal colony until March 1887, with the signing of the Lisbon Protocol. By 1935, this treaty was nearly half a century old, but its basic provisions still held: primarily that China recognised the “perpetual occupation and government of Macao” by Portugal. However, the protocol also required Lisbon to agree never to surrender Macau to a third party without Chinese agreement.

Some British commentators questioned whether Lisbon or Tokyo would care about honouring this clause. China looked weak – Japanese encroachments in the north, foreign-controlled treaty ports along the coast, warlords running amok from Hubei to Xinjiang. Cash-strapped Lisbon, with US$100 million dangled before it, might decide that a fallout with Nationalist China was a price worth paying for this windfall and to rid itself of a costly colony. Japan, having invaded Manchuria and now eyeing the rest of northern China, might ignore the provisions of the Lisbon Protocol.

If Portugal chose to take the cash, what could China do? Invade Japanese-occupied Macau and give Tokyo an excuse to attack southern China? Appeal to a League of Nations, which had been so ineffective against Japan in Manchuria? Invade Portugal, 10,000km away? Not likely.

The difference between Manchuria and Macau, of course, was the proximity of that key outpost of the British Empire, Hong Kong. Some newspapers reported that London, an old ally of Portugal, had immediately told Lisbon to not accept Japan’s offer.

It’s difficult to untangle what actually happened in the spring and summer of 1935. Did Japan make an offer? Did Portugal seriously consider it? Did the British tell the Portuguese to resist? Was the whole story perhaps concocted by a Hong Kong journalist desperate for a payday who cooked up the profitable rumour at the bar of the Hongkong Hotel, on Pedder Street, where hacks gathered to drink and gossip? Or did someone – perhaps Japanese intelligence looking to spread misinformation, or Chinese intelligence trying to draw attention to Japanese intentions in southern China – feed a yarn to some susceptible journalist in the hope he would report it back to London? It would not have been the first time.

Not one yard of Portuguese territory is for sale to Japan, or any other nation. Neither is any Portuguese territory to be ceded under any circumstances

Either way, on May 15, the Portuguese Ministry for the Colonies in Lisbon was vehemently denying Macau was for sale: “Not one yard of Portuguese territory is for sale to Japan, or any other nation. Neither is any Portuguese territory to be ceded under any circumstances.” There was no denial a Japanese offer had been made.

Several newspapers pointed to the ministry’s wording: that no Portuguese territory was for sale to Japan, “or any other nation”. Had London warned Lisbon off any sale to Tokyo, then made a counter offer?

Some commentators suggested Japan might attempt a naval blockade of Macau given the minimal Portuguese naval presence in the South China Sea. Again, it was rumoured London had let it be known that the Royal Navy’s three-squadron-strong Far East Fleet would not allow that to happen.

Then the situation became curiouser. On May 28, the Portuguese again denied that any territory was for sale, and this time Macau specifically was mentioned. However, the denial came not from Lisbon, but from the Portuguese embassy in Berlin. It was a reaction, the embassy said, to rampant and alarmist speculation in German newspapers about a potential Lisbon-Tokyo deal over Macau.

The story did not go away. It was still being trotted out in US and European newspapers in July 1935, as well as in the South China Morning Post and Singapore’s Straits Times. Some US newspapers opinioned that Lisbon’s denials might be a gambit to talk up the price.

By the end of that summer, Tokyo seemed to change tack and the idea of an outright purchase disappeared. It was reported that a Japanese envoy had approached Macau’s colonial government with a proposal for creating a “Japanese settlement”, essentially a village, close to Zhongshan, on the Chinese mainland, where Japanese merchants could live and trade. Portuguese authorities in Macau were reported to be considering the request. Japan’s apparent loss of interest buying the territory was likely due to another proposition put to Lisbon.

With the Nanjing government adamant in refusing landing rights to Pan Am, the airline had turned to Macau and, in September 1935, had been granted a sea-landing location at the entrance to the Pearl River Delta. From there, passengers and post could be disembarked from the Pan Am China Clipper and take regular ferries to Hong Kong and Guangzhou. With landing rights assured, Pan Am immediately began negotiations to build a radio-telegraphic and radio-chronometric station.

The USPO’s delighted Harllee Branch was reported to be planning a San Francisco-Honolulu-Manila-China line, ending at Macau and operated by Pan Am China Clippers. Macau was proving as strategically useful to Pan Am as it had been to the Portuguese fleet in the 16th century.

The service started in November 1935, when a China Clipper with 18 sleeper passengers on board took off from San Francisco Bay in the late afternoon. Seventeen hours later it landed in Honolulu in the morning sunshine. Refuelled, the Clipper took off again and spent a night at a series of Pacific islands – Midway, Wake and Guam – before arriving at Manila, a half day’s flight from Macau and the ferry connection to Guangzhou. From there, passengers could connect to flights to Shanghai, Nanjing and Beijing. The 14,500km journey would have taken three weeks by boat.

At the same time, Pan Am was launching clipper services to South America, as far as Buenos Aires. Britain’s Imperial Airways, Germany’s Lufthansa and airlines from France and the Netherlands were also beginning transatlantic services and pushing their networks east to connect with their Asian empires.

Branch got to launch his China Clipper stamp – the first was posted to US president Franklin Roosevelt from Manila. In 1937, the Pan Am Clipper fleet was joined by a Sikorsky S-42 flying boat with a slightly larger fuel capacity. But it wasn’t all smooth flying. For reasons that have never been fully determined, the Hawaii Clipper disappeared somewhere between Guam and Manila in July 1938 with the loss of nine crew and six passengers.

Japanese airlines continued to expand, too, with more flights into Korea and Manchuria, and new services on converted military flying boats to Sakhalin island, Saipan and Palau, in the western Pacific. The newly dubbed Imperial Japanese Airways ran several long-haul trial flights to Iran and even to Italy in 1939, but then the invasion of China and the demands of war overtook civilian air route development.

It’s likely that Japan decided its long-term expansionist strategy in Asia would not ultimately require having to pay Lisbon US$100 million. Arguably, Japan always had another plan for China, and eventually took the country by force – Manchuria had just been the start. By the end of 1941, it had conquered southern China and Hong Kong.

The Japanese emperor no longer had any need for Macau, which remained quietly neutral, like its colonial master Portugal, throughout World War II.