Eric Yuan devised the platform as a humdrum corporate communications app, never anticipating it would become a lifeline for the locked down. But with such stellar success comes great responsibility, not to mention many detractors.

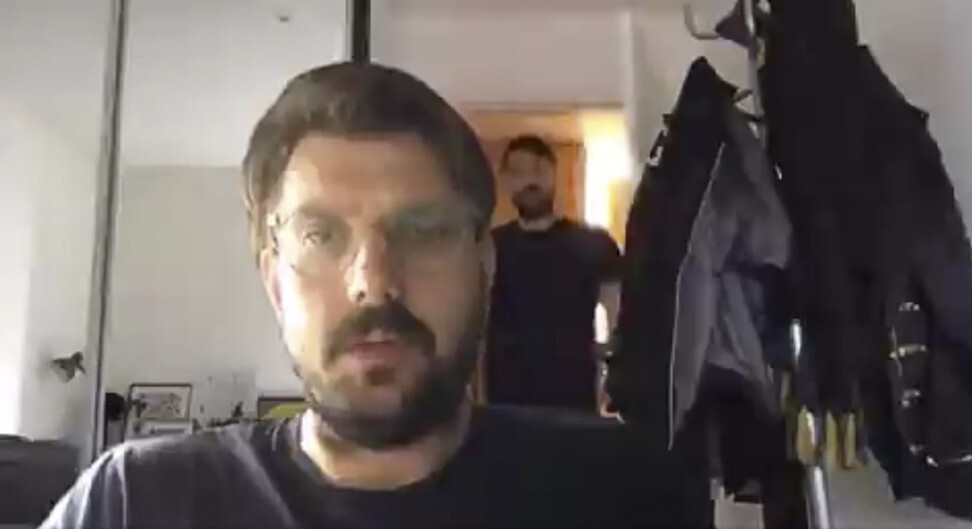

Like the rest of us, Eric Yuan is taking things day by day right now. The Chinese-born American founder and chief executive of teleconferencing software company Zoom gets up each morning, after three or four hours’ sleep, and nervously checks the previous day’s capacity numbers to make sure the servers have not been overwhelmed by traffic. Then he begins the long slog of videoconference calls from his home in the San Francisco Bay Area. “It’s too many Zoom meetings,” he says, via Zoom. “I hate that.”

It’s not helping that, with schools and colleges cancelled, Yuan’s three children are at home clogging up the Wi-fi. The other night he got an email from a mother about a troll who invaded her child’s Zoom virtual classroom and showed inappropriate content. Afterwards, he couldn’t sleep.

The only thing keeping Yuan sane is his mother, who has been living with the family. Each day for lunch she brings him a noodle or rice dish she’s made, scolding him when he forgets to eat it. And if Yuan has time after dinner, mother and son take a walk in his garden. “I tell myself, every morning when I wake up, two things,” Yuan says. “Don’t let the world down. Don’t let our users down.”

A month ago his company was merely a fast-growing success story in the somewhat boring universe of enterprise communications. Today, suddenly, Zoom is critical infrastructure. As billions of people around the world socially distance to blunt the toll of the coronavirus, those lucky enough to still have jobs are trying to work them from home. To do so, they are turning to remote collaboration tools; messaging platforms such as Slack and videoconferencing software like Cisco Webex, Microsoft Teams and, especially, Zoom, have seen explosions in traffic.

Zoom’s new traffic isn’t just from workplace conference calls. Its simple interface – users enter a meeting with one click – has made it perfect for millions of people who want to maintain at least a diluted form of human contact. Schools and colleges are teaching classes on Zoom; Alcoholics Anonymous groups are using it to hold meetings; people are going to Zoom family reunions and happy hours and trivia nights. They are dating, talking to therapists and having birthdays.

In photos his sister posted on Twitter, Hunter Lee, a Walmart food sales associate in the United States, celebrated turning 21 with family and friends looking out from the corner of the room, their webcam images tiled on the screen. A few days earlier, British psychiatrist Rob Baskind had Zoomed into the funeral of his mother, who had succumbed to the virus. For many, Zoom has become not just a way to socialise, but the social fabric itself.

Yuan is as surprised as anyone at this turn of events. He didn’t set out to create a business that would be a household name, in these circumstances or any others. And while it’s a testament to the technology that it has mostly handled a twentyfold surge in use, in other ways the company, like many others, has been blindsided by the past few weeks.

“I never thought that overnight the whole world would be using Zoom,” he says. “Unfortunately, we did not prepare well, mentally and strategy-wise.” Historically, giant communications networks – Facebook, Twitter, AT&T – have all had their growing pains, but none had to go through them in just a few weeks. In times as vertiginous as these, even success can be brutal.

Yuan has always been frustrated by the inconvenient fact of distance. The younger son of husband-and-wife mining engineers, he grew up in Taian, in China’s Shandong province. Studying maths and computer science at Shandong University, he had to take a 10-hour train ride to see his girlfriend, a problem he solved by marrying her at the age of 22.

Yuan, now 50, idolised Bill Gates and was determined to work in Silicon Valley. His visa application, though, was denied on his first try, and on the next seven, after a bureaucratic mix-up. It took nearly two years of persistence, but on the ninth attempt, he got into the US.

Yuan found a job in California at Webex, then a start-up. By the late 1990s, technology had made real-time video chat – long a sci-fi staple – a reality, and Webex was among the first to make a working product. Yuan was one of 10 engineers when he joined Webex in 1997, and by the time Cisco Systems acquired it a decade later, he was vice-president for engineering, managing 800 workers.

Seeing the rise of the iPhone and its imitators, he became convinced the company needed a product that worked on mobile phones, not just personal computers. Cisco’s leadership didn’t agree, and Yuan left in 2011 to found Zoom Video Communications, taking a contingent of engineers with him.

Headquartered in San Jose, Zoom built a research and development team in China, where engineers work for far less than their American counterparts. Yuan contacted every company that considered Zoom but went with a competitor, something he still does.

Zoom was appealing, in part, because it was a neutral platform. It wasn’t tethered to Apple, like FaceTime, or Google or Microsoft, like Hangouts and Skype. Anyone, even someone without an account, could join a meeting, from any device, just by clicking a link in a text or email. Hosts could record video and audio and generate transcripts, and it was easy for people to screen-share.

If you can keep your meetings under 40 minutes and 100 participants you can use Zoom for free; clients who pay a monthly fee of US$19.99 per meeting host can gather as many as 1,000 people on a single video call.

A video producer named Dan Crowd created one recently that looks like a normal office but is a trompe l’oeil animation in which the door opens and Crowd himself walks in, obliviously interrupting his own meeting.

In a world of philosopher-chief executives promising to transform the human condition through ride-hailing or shared workspaces, Yuan is passionate about videoconferencing software and uninterested in declaiming on other topics. After Zoom’s valuation passed US$1 billion in 2017, he publicly scoffed at the unicorn label, saying it did not mean anything unless the business continued to grow.

Zoom had an early glimpse of the coronavirus at work. The company’s Chinese offices and R&D facilities closed in late January (they have since reopened). “We were thoughtful and a little bit paranoid about what was to come, which has turned out to be a good thing,” Kelly Steckelberg, the company’s chief financial officer, says by Zoom from her home.

Zoom was quick to close its San Jose headquarters, sending employees home two weeks before Santa Clara County issued its shelter-in-place order – a decision that was admittedly easier for a videoconferencing company.

After Japan and Italy closed schools in late February and early March, Zoom removed the time limits on its free product for educational institutions in those countries. It continued to do so as school shutdowns spread globally. Still, Yuan thought the disruption would be brief. Then, in mid-March, his children’s schools closed. When Zoom’s daily users passed 100 million, he began to realise what the crisis would mean for his company.

Since then, it’s been a sprint to cope with the ballooning demand. When you are on a Zoom meeting, the app adjusts bandwidth so that one participant’s poor signal doesn’t degrade another user’s experience. Zoom does this by linking each participant to the closest of 17 data centres it rents worldwide; if one centre is overloaded, it sends traffic to the next closest.

To keep up with its new audience, the company has added two data centres, and it’s been buying more of the cloud storage capacity it uses for surge protection. Zoom relies heavily on Amazon Web Services, as well as on Oracle, for cloud computing. So far, these efforts have paid off: there have been complaints of poor call quality, and Zoom’s website was briefly down for maintenance, but the platform has bent, not broken, under the new demands.

On March 24, Consumer Reports detailed how Zoom’s privacy policy let it share the content of video chats with ad-tracking companies. The piece highlighted how hosts don’t need participants’ permission to record videos, or make and share transcripts; hosts can read texts that participants exchange on the app’s chat function, too.

The publication also noted Zoom’s panopticon-like attendee attention tracking tool, which alerted a host if people clicked over to a different window on their computers for more than 30 seconds, suggesting they were otherwise occupied.

Two days later, tech site Motherboard revealed that Zoom’s iPhone app, which was built using Facebook software, was sending user data to the social network giant without alerting users. On March 30, former US National Security Agency hacker Patrick Wardle blogged about flaws that would let attackers put malware on a computer or hijack the webcam and microphone.

The next day, The Intercept website reported that while Zoom claimed to guard user data using end-to-end encryption – the strongest available privacy protection – that wasn’t true. And on April 3, University of Toronto researchers published a paper revealing that the company sometimes routed meetings through servers in China even when all the participants were outside the country, raising the possibility that Chinese authorities might try to listen in.

Zoom was also attracting the interest of trolls. School teachers getting their classrooms up and running found their sessions disrupted by “Zoombombers”, with malicious interlopers joining to shout racist epithets or screen-share pornography. White supremacists started Zoombombing virtual Torah sessions and webinars on anti-Semitism with images of swastikas.

We recognise that there is a discrepancy between the commonly accepted definition of end-to-end encryption, and how we were using itOded Gal, chief product officer, Zoom

Zoom has since amended its privacy policy to make clear that video and chats would not be shared; updated its iPhone app to stop sending data to Facebook; and patched the vulnerabilities that Wardle found.

On April 1, Zoom’s chief product officer, Oded Gal, addressed the encryption issue in a repentant, if euphemism-plagued, post on the company blog. “While we never intended to deceive any of our customers,” he wrote, “we recognise that there is a discrepancy between the commonly accepted definition of end-to-end encryption, and how we were using it.”

That day, Yuan posted his own apology and said that Zoom would probe for further security weaknesses; remove the attention tracker; offer training against Zoombombing; change the default screen-sharing settings to make things harder for trolls; and issue a transparency report detailing government data requests.

When the University of Toronto report was published on April 3, Yuan responded the same day, blaming the China server issue on Zoom’s scramble for capacity and announcing that the company had corrected it. A day later, Zoom users got an email telling them that all meetings would now automatically have passwords.

Yuan argues that Zoom’s issues stem not just from its explosive growth but also from the new types of users flocking to it. “We built this as a platform for knowledge workers, for businesses with IT departments,” he says, sitting against a digital backdrop of the San Francisco hills. For Zoom users in non-pandemic times, he goes on, there would be a tech-support person helping them set up their settings and reminding them to have a password.

In a work setting, for better or worse, we are more resigned to the idea that our boss will snoop on us so that we don’t slack off. Unlike schools and happy-hour organisers, Zoom’s corporate clients have their own data and privacy policies. And at the office, even neo-Nazis try to watch their language.

We have to embrace this new paradigm and figure out how to make it workEric Yuan, founder, Zoom

Yuan’s explanations are more convincing for some lapses than others. If anything, expectations should be higher for a collaboration app given that it engages with sensitive data. “I’m granting access to a camera, a microphone, to the screen, everything that happens on the computer,” says Ralph Loura, chief information officer at electronics manufacturer Lumentum. Zoom, in other words, should be the last company to be casual about security.

It may be that the main trait that let Zoom succeed is now haunting it. Its focus on simplifying the arcane and buggy process of videoconferencing has created a product that’s also simpler for others to manipulate. Yuan concedes that there could be a tension between security and simplicity. “It may be time to revisit that,” he says.

At some point, though, the pandemic will end. Will Zoom go back to being a corporate videoconferencing company? “I have no answer,” Yuan says. His board asked him that very question a few days earlier, and he told them the same thing. Currently, while many new users aren’t paying for the service, some have signed up for Zoom’s paid tiers, and some corporate clients upgraded when they sent their workforces home.

On April 1, AllianceBernstein analyst Zane Chrane said the pandemic could generate “a few hundred million” in additional revenue. That’s on top of the more than US$905 million Zoom predicted for the coming financial year in its last earnings call, a Zoom webinar held on March 4, just after it closed its headquarters.

Given the choice, Yuan makes clear, this isn’t the path he would have chosen for himself or for the company. But he says he no longer pretends he’s in control: “You can’t go back, that would not be responsible. For now we have to embrace this new paradigm and figure out how to make it work.” Zoom is “now owned by the whole world”, he adds.

Then he has to go. It’s lunchtime, and his mother is patiently waiting.

Text: Bloomberg Businessweek