- The London-based Australian has dedicated his prolific career to bringing crises, corruption and crimes against humanity to the public sphere

- Ironically, he got his start in journalism under false pretences

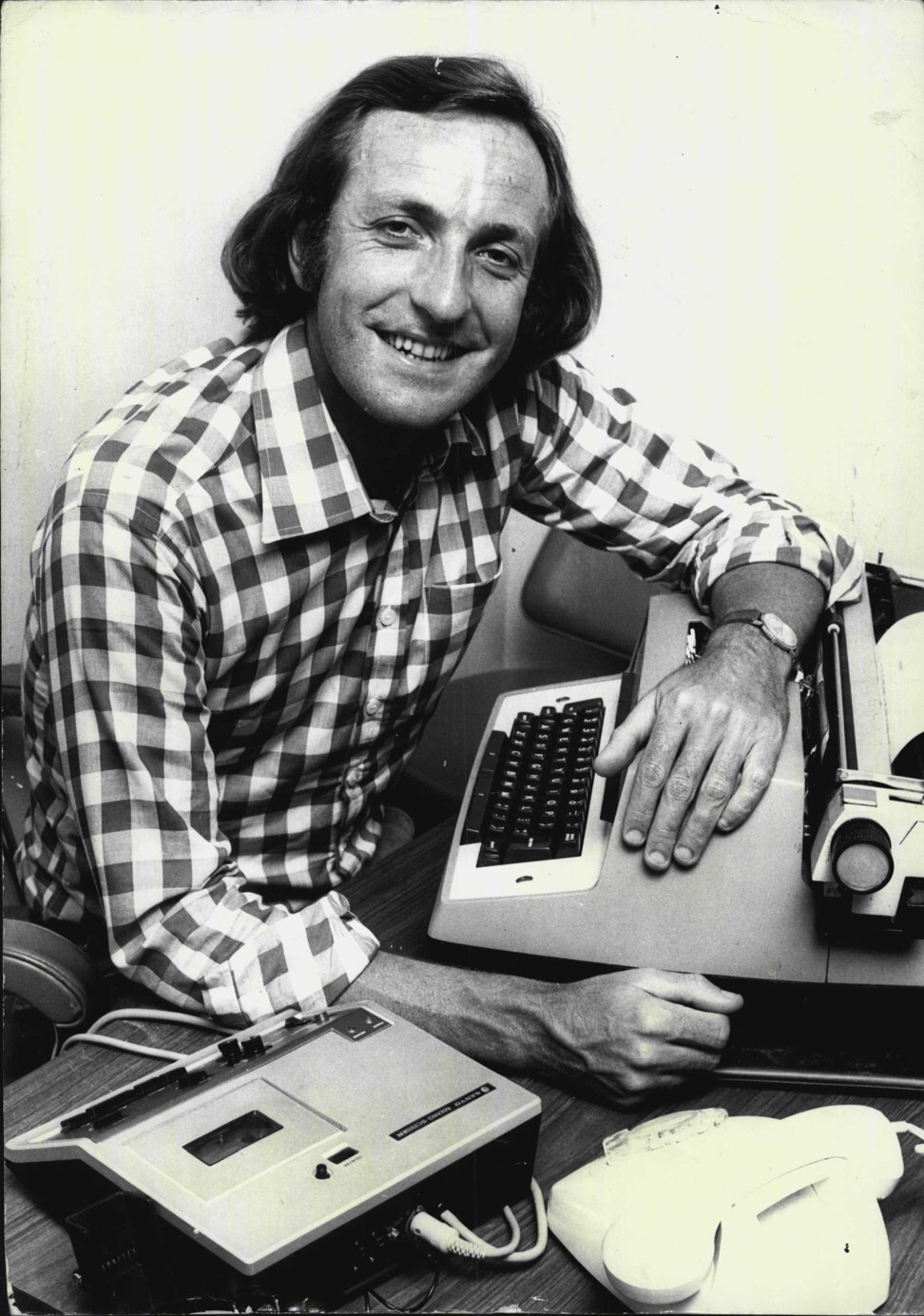

Back in 1963, when a newspaper like the Daily Mirror could expect to sell close to five million copies a day, Australian journalist John Pilger was desperately searching for a job in swinging London.

Interviewed by the Mirror’s then assistant editor, Michael Christiansen, Pilger found he seemed to be more interested in recruiting players for the paper’s cricket team.

“You’re just what we want,” he boomed. “An Australian. What do you do best?”

“I bowl,” bluffed Pilger, who knew nothing about the game. “I spin bowl.”

It was the right answer. Pilger was hired on the spot and appointed assistant to the sub-editor in charge of television, gardening, fishing and pets. Not exactly glamorous, but that strategic bluff would serve him well.

It wasn’t long before he was tackling rather more compelling subjects, in time gravitating to chief foreign correspondent, and in subsequent years, Pilger became one of journalism’s foremost crusaders, training his investigative instincts on injustice and government-sponsored duplicity all around the world.

And he continues to do so, undaunted by the fact that this October will mark his 81st birthday. His trademark has always been to sidestep the accepted version of the facts, a modus operandi that served him well during the Vietnam war, in the apocalyptic post-Pol Pot Cambodia, the killing fields of East Timor and countless other hotspots.

So little surprise, then, that as the coronavirus brings normal life to a halt in many countries, Pilger is seeing things from his signature angle, a view from outside the mainstream that has solidified and sullied his reputation over a decades-long career, depending on who you ask. But that also explains his longevity. And on the phone from his home in London, it is evident that becoming an octogenarian hasn’t mellowed him in the least.

His most recent documentary was last year’s The Dirty War on the NHS, which given the current global pandemic and strained health care systems in every country affected, feels oddly prescient.

“I suggest we look beyond this virus and ask how our current state of fear and its mass obedience will be exploited in future. Will the workers ‘stood down’ ever see their jobs again? Will artificial intelligence consume freedoms that have been suspended? As Edward Snowden says, the disease of mass surveillance will outlast this pandemic. Will Julian Assange [the Australian founder of WikiLeaks], persecuted for the crime of truthful journalism, survive?”

“Within a week, [a pirated version] appeared on the internet with Chinese subtitles – including the Tiananmen Square sequence. Then a friend called from Shanghai to say he had bought a DVD of the film in his local shop – unedited and openly on sale.”

No one doubts the ruthless reaction of Beijing to separatists, but as a reporter, I would like to see for myselfJohn Pilger

“It’s difficult to separate the Uygurs from the barrage of anti-China denunciations coming from the US, most of which have a script familiar to those who follow America’s ‘soft’ campaigns against its strategic enemies,” he says. “The leading US media are invariably the cipher. ‘In China, every day is Kristallnacht’, declared The Washington Post [last November], likening China’s treatment of the Uygurs to that of the Nazi genocide of the Jews.

“That’s not untypical; it reads as if it has been written by the US Agency for International Development or the National Endowment for Democracy, which fills in for the CIA. No one doubts the ruthless reaction of Beijing to separatists, but as a reporter, I would like to see for myself.”

Pilger’s first documentary, The Quiet Mutiny (1970), featured American soldiers expressing their disgust at the war in Vietnam and admitting that their more unpopular officers often got “fragged” – shot – by their own side.

Pilger modestly described the film as “something of a scoop”. Australian journalist Phillip Knightley, writing in his history of war and journalism, The First Casualty (1975), ranked The Quiet Mutiny among the most important reports of the war. A furious television executive accused Pilger of being “a threat to Western civilisation”, which Pilger took as a compliment.

Following his 1979 visit, Pilger’s searing documentaryYear Zero: The Silent Death of Cambodia was screened in 50 countries, provoking worldwide revulsion and pity followed by a rush to donate money.

That Cambodia should have suffered so grievously, and was continuing to do so because of geopolitical posturing, prompted people from all walks of life to donate some US$45 million, which was used to restore water supplies, stock hospitals, shore up orphanages and open a clothing factory.

The late American journalist Martha Gellhorn praised Pilger for taking on “the great theme of justice and injustice”, saying he belonged to “an old and unending worldwide company, the men and women of conscience”.

American political activist Noam Chomsky remarked that Pilger’s work had been “a beacon of light in often dark times”, and John Simpson, BBC stalwart and doyen of international affairs correspondents, said, “A country that does not have a John Pilger in its journalism is a very feeble place indeed.”

Inevitably, Pilger has come in for a hefty measure of criticism from those whose feathers have been ruffled by his strongly held, often controversial views. Most publicly, the right-wing columnist Auberon Waugh coined the verb “to pilgerise”, which he claimed was “to present information in a sensationalist manner to reach a foregone conclusion”.

Waugh, who died in 2001, was a satirist and a habitual tease who could rarely resist poking the bear, but others reacted to Pilger’s oeuvre far more fiercely.

After it was broadcast on British television in 2002, Pilger’s Palestine is Still the Issue provoked furious protests from the Israeli embassy, the Board of Deputies of British Jews and the Conservative Friends of Israel, who vouched it was inaccurate and biased. Even Michael Green, who was both of Jewish descent and – ironically – chairman of the company that had made the film, raised objections.

However, an independent commission ruled that the documentary was reasonably balanced. Perhaps the most fulsome praise has come from a fellow journalist, Anthony Hayward, whose book Breaking the Silence (2008) appraised Pilger’s documentaries and journalism in general. “His work, particularly his documentary films, has also made him rare in being a journalist who is universally known, a champion of those for whom he fights and the scourge of politicians and others whose actions he exposes.”

Pilger was on the scene when US presidential candidate Robert Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles, in June 1968; he has shone a spotlight on dozens of disadvantaged communities, be they impoverished Mexicans, beleaguered Palestinians or the Aboriginals of his native Australia; and he has tackledthird-world debt, which he examined in the self-explanatory War by Other Means in 1992.

His 2004 book Tell Me No Lies features his own work but also that of other crusading journalists, including Seymour Hersh, who broke the story of the My Lai massacre, Seumas Milne, who uncovered a government-sponsored dirty tricks campaign against Britain’s striking miners, Günter Wallraff, the German undercover reporter who had written extensively about the mistreatment of foreign workers, and – an unlikely ally – Jessica Mitford, the English aristocrat who emigrated to the US and exposed the money-grabbing practices of the funeral industry.

However, it is Asia that has called Pilger back time and again, notably when he made a revelatory documentary in 1994 with his long-time collaborator David Munro about the plight of East Timor.

While viewers were shocked by Death of a Nation’s accounts of the genocide that had followed the Indonesian invasion in 1975, they were appalled to learn that massacres had been carried out with the collusion of America, Britain and Australia.

For Pilger, the story of East Timor illustrates the extent to which “most ‘news’ comes from a handful of sources – mostly American or Anglocentric”, he says. “The social, economic and political agendas of Western elites dominate. In Australia, for example, Rupert Murdoch controls 70 per cent of the capital city press.

“The media ‘world view’ is, to use the correct word, imperial. That’s why news of East Timor is rarely found in what is known speciously as the ‘mainstream’; yet what has happened in East Timor in my lifetime is an instructive mirror of the struggles of much of humanity. [Likewise], Palestine is not reported truthfully because its oppressor, Israel, has been granted impunity by the West: [both] governments and media.”

Pilger’s thoughts were given added weight by José Ramos-Horta, at the time of the film’s release East Timor’s foreign minister-in-exile and later its first president. “Our struggle for the recognition of our human rights was in the doldrums until Death of a Nation was shown around the world,” he said. “It changed everything for us. It gave us a visual and factual point of reference – something we could show to governments and say: ‘Do you find this acceptable?’ I have no doubt it was crucial in bringing forward our liberation and saving countless lives.”

Pilger – who habitually distances himself from the stress of his workload with “a long swim and a very cold beer” – added that making the East Timor documentary was “the most challenging to my sense of self-preservation and the most inspirational”.

The media ‘world view’ is, to use the correct word, imperial. That’s why news of East Timor is rarely found in what is known speciously as the ‘mainstream’John Pilger

While various talking heads play an intermittent role in The Coming War on China, the film’s prime focus falls on everyday people who find themselves underfoot an expansionist American military. Pilger interviewed radiation victims in the Pacific islands and doughty protesters in Japan and Korea who are struggling to get rid of American bases or at least prohibit their expansion.

In the final few frames – following footage of Donald Trump inciting his followers at a campaign rally – he offers some carefully chosen words on the conundrum in which Asia and the rest of the world finds itself early in the 21st century.

“We don’t have to accept the words of those who conjure up threats and false enemies that justify the business and profit of war if we recognise there is another superpower.

“And that’s us – ordinary people everywhere, like the people of Okinawa, Jeju, the Marshall Islands, China and the United States. By speaking out they deliver a warning to all of us: can we really afford to be silent?”

While he’s still not much of a bowler or indeed any sort of cricketer, Pilger’s journalistic delivery has never been short of fearsome.

“Fearsome? Gosh. I don’t think of it like that. Since I started my own newspaper with a school friend at the age of 12, I always wanted to be a journalist. It’s a privilege to be allowed into people’s lives, occasionally to be their voice, and – 80 years old or not – I have no intention of giving it up.”