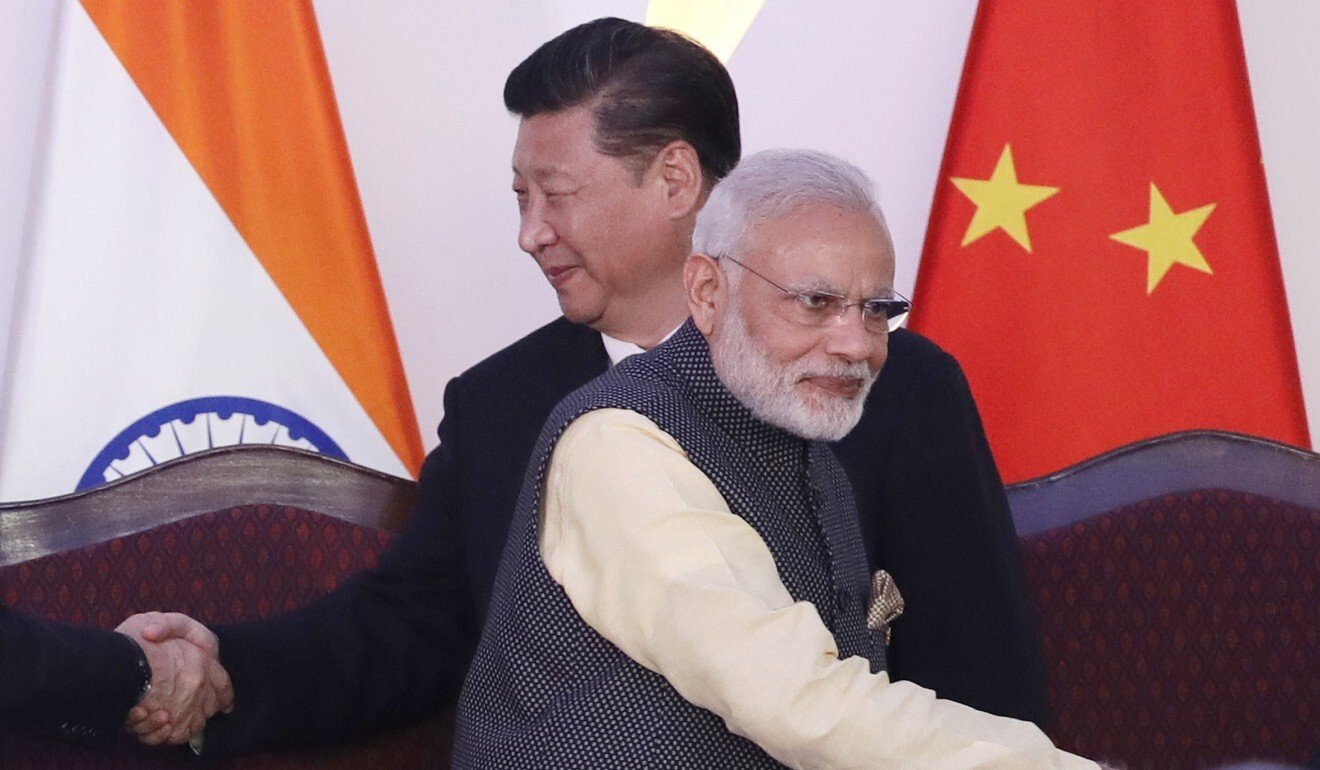

The Make in India movement is gaining ground amid rising anti-Chinese sentiment but with Indian companies heavily dependent on Chinese capital, Narendra Modi’s push for self-reliance could be self-destructive

In April, a month after the Indian government ordered the first phase of a countrywide Covid-19 lockdown, an online campaign began to gain steam, a collective vow to buy only swadeshi – home-grown – goods, to help alleviate the economic “agony” caused to local businesses by the pandemic. But more than just buy local, this was a call, specifically, to avoid anything made in China.

In one way reminiscent of Mahatma Gandhi’s non-violent resistance to the British Raj, where Indians under occupation forewent Manchester-sewn textiles in favour of “homespun” cloth, the difference between then and now, of course, is that China is not an occupying force. But that is where campaign organiser Swadeshi Jagran Manch (SJM) might disagree.

#Boycott_China_MNCs took off as a hashtag, as did #MadeInIndia, and tweets vowing to not use Chinese products have continued to dominate Indian trending pages.

“Let’s all #RemoveChinaApps from our phones & within a year Chinese Hardware too. It will save us 50 Lac Crores that we pay as Trade Surplus to China! 25% of our GDP. Jai Hind!,” proclaimed one tweet.

Others wanted to invoke the past: “Just as India led its Freedom Struggle, the same way we consumers have to lead this struggle and free ourselves from Chinese products.”

This is in line with years of rising jingo-populism in India, amplified by television anchors on Hindi- and English-language news channels advocating the deletion of Chinese apps for spreading fake news, stealing personal data, and as revenge for China’s handling of the coronavirus. Responding to a panellist debating alternatives to Chinese products, nationalist “news” anchor Arnab Goswami remarked: “See the pictures of what’s happening today in Ladakh. See our men out there fight for our country with life and limb. Will we allow the carpet bombing of our consumer industry?”

Even stalwart BJP leaders such as Minister for Road Transport and Highways – and RSS devotee – Nitin Gadkari have made statements urging Indian industries to take advantage of the “great hatred” against China.

As the latest indicators from the Pew Research Center think tank show, Indians’ favourable views towards China nearly halved from 41 per cent in 2017 to just 23 per cent today, exacerbated by the virus and prolonged by the current India-China border dispute in Ladakh.

Yet India remains heavily dependent on Chinese capital, and requires Chinese expertise in sectors such as artificial intelligence and 5G. While caution in dealing with China in these areas might be justified, prolonged negative sentiment and the boycotting of Chinese goods might end up harming Indians and their own tech economy. But as the April crusade has proven, SJM’s appeal has spread beyond the far-right and the subcontinental “blood and soil” types, and fuelled the angst of the Indian middle class.

“Many in my circle have stopped using Chinese products,” says Gyan Srivastava, a middle-aged chemical engineer and follower of SJM based in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh. “You’ll see the impact soon.”

On June 2, Home Minister Amit Shah said, “India’s 130 crore [1.3 billion] population is our strength and if they decide not to buy foreign goods, India’s economy will see a jump.”

SJM gained notoriety in tech in 2018, with its campaign for the cancellation of the US$16 billion acquisition of home-grown e-commerce start-up Flipkart by United States retail giant Walmart. Led by co-convener Ashwani Mahajan, SJM members met India’s then minister for commerce and industry, Suresh Prabhu, to complain the deal was “illegal”, “anti-farmer” and disadvantaged local businesses. Prabhu promised to look into it but the deal went through, marking the largest-ever foreign acquisition of an Indian internet start-up.

While that campaign got them noticed by a greater number of Indians, SJM has been opposed to trade with China from the outset, and has accused the Chinese Communist Party of unfair trade practices and called for tariffs. But SJM’s April incitement was one of the biggest signals to date of public resentment towards the Chinese, a sentiment previously most visible when anti-Chinese feeling was stoked by a 2017 rally in Delhi’s Ramlila Ground, in which more than 100,000 people demonstrated against alleged Chinese dumping of cheap toys and electronics into the Indian market, as local manufacturers struggled. “When we opposed [global trade] in 1991,” says Mahajan, referring to the year India opened to foreign investment in the face of economic crisis, “people accused us of driving [the economy] back to the stone age. Now, more and more are coming into our fold.”

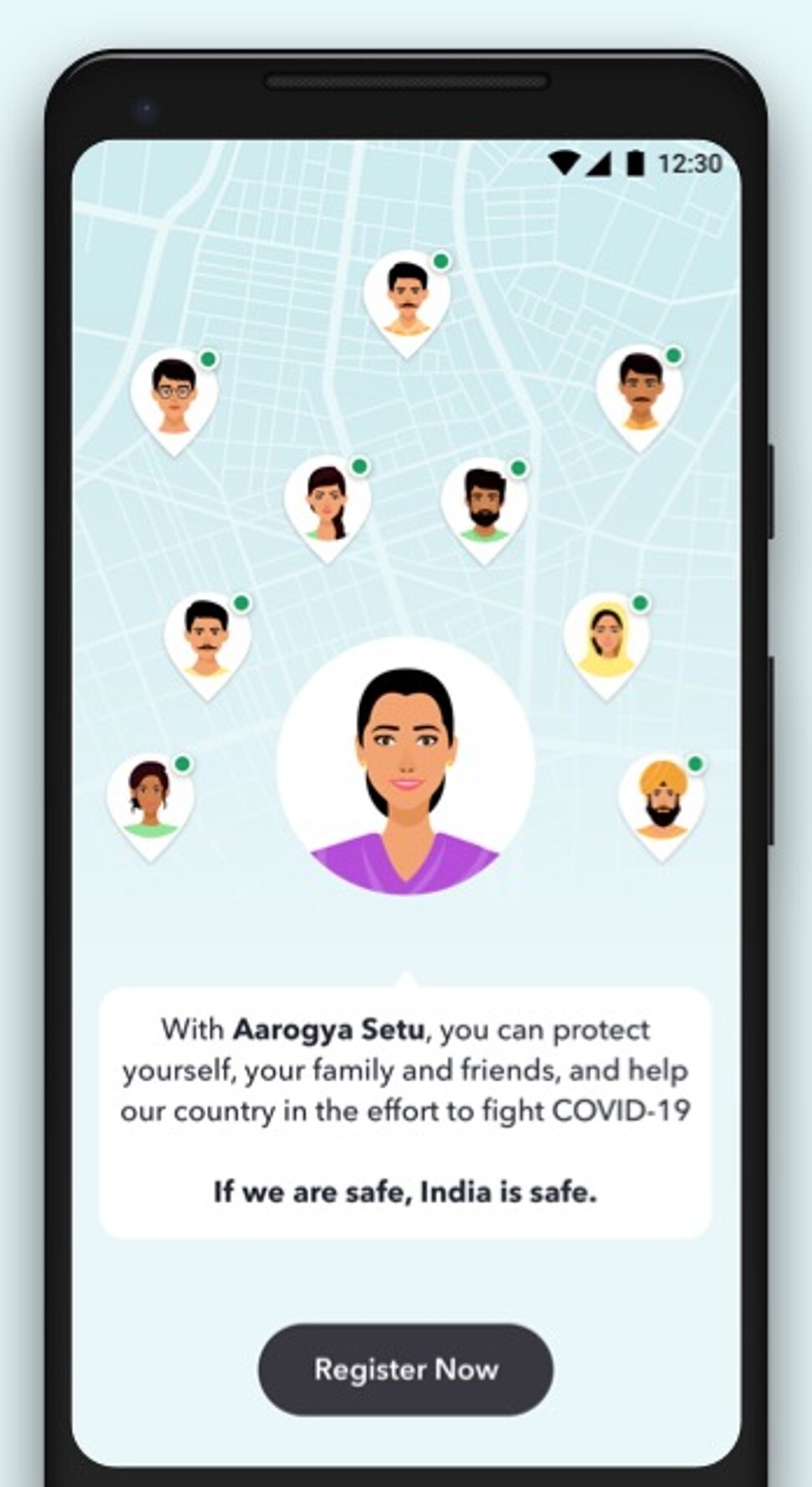

And the April campaign showed him to be right. Or at least not completely wrong. Texts and tweets listing out “desi” – a term for the people, cultures and products of the Indian subcontinent – alternatives to popular Chinese apps, along with download links, have gone viral. The momentum is such that TikTok clone Mitron TV, released in May, became the No 2 Android app in India that same month – with five million downloads – trailing behind only the state-backed Covid-19 contact-tracing application Aarogya Setu, with more than 100 million downloads.

One viral WhatsApp message read: “Mitron has created an indigenous version of TikTok. Install it and remove the Chinese app TikTok. Likewise say goodbye to the ZOOM app with video conferencing and meeting. Our Indian app Saynamaste is available, which is good and also very fast. No user ID is also required to be created. Tata has launched an Indian shopping site tatacliq.com for online shopping. Skip Amazon.”

It was later found that Mitron TV’s publisher bought the source code from a developer in Pakistan, India’s fiercest rival: not a good look for an app whose name means “friends”, a word frequently used by Modi to address public rallies. Another mobile app, Remove China Apps, rose up the charts in record time, crossing millions of downloads on Google’s Play Store within weeks of its launch in May, claiming its purpose was to support Modi’s Atmanirbhar Bharat – a self-reliant India pledge – by identifying an app’s country of origin. Both the appswere removed by Google from the Play Store early this month, provoking a massive backlash. The Mitron app is now back.

How Chinese video app TikTok conquered the world

Before the SJM lockdown campaign, the Indian government had already decided foreign direct investment (FDI) from countries that “share a land border” with India would need state approval. Which, given the limited nature of any potential financial impact from India’s other border-sharing neighbours – think Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh – appears to be an underhand swipe directed firmly at China. But it wasn’t unfounded. The People’s Bank of China had recently bought a 1.01 per cent stake in HDFC, India’s largest bank by market capitalisation. The policy shift would curb “opportunistic takeovers/acquisitions of Indian companies due to the Covid-19 pandemic”, the government stated.

In the end, it took a pandemic to finally animate SJM’s long-term dreams of a return to a pre-1991 economic isolationism.

Whether a publicly listed firm seeking Chinese investment, an Indian venture-capital firm that has taken money from Chinese investors, or an Indian technology company with existing Chinese investors, any further investment into India would have to jump through as yet unspecified hoops for approval.

But India’s FDI-halt for border countries and the boycott of Chinese goods are unlikely to work to its advantage. Indeed, an economic boycott of China without a carefully thought-out policy could prove disastrous – Indian exports to China in 2019 were worth US$17 billion, accounting for 5.3 per cent of the country’s total exports, while Chinese exports to India stood at US$70.3 billion, constituting about 3 per cent of its exports.

On May 12, during a televised announcement extending the coronavirus lockdown, Modi made an impassioned speech: “If every Indian strives to purchase only indigenous goods, India can become self-reliant in five years,” he said. Modi has eschewed press conferences and his characteristic 8pm briefings are the only time he speaks directly to Indian citizens. In his most recent appearance, he urged millions of his followers to be “vocal” in their support for “local” products, and promote them proudly. The phrase #VocalforLocal was soon added to the hashtag lexicon, with millions pledging allegiance on social media.

Rolling with the “self-reliance” theme, the Indian government floated an innovation challenge, and hand-picked 10 desi companies to develop a Zoom clone: #MadeInIndia video-conferencing software. But while Zoom burned through US$150 million to become what it is, the Indian government was ready to shell out just US$130,000.

“Zoom likely spent 50M+ just in caching servers, local POPs, dark fibre, & datacenter capacity,” tweeted venture capitalist Hemant Mohapatra. “If you want people to build a seafaring ship, don’t offer lego blocks.”

“This is a knee-jerk reaction and a game of perception management,” says Anand Lunia, managing partner at venture-capital firm India Quotient. “Chinese money has been one of the most consequential sources of growth capital for Indian start-ups.”

When India Quotient was founded, in 2011, the country’s online commerce industry was in its infancy, but Flipkart had by then already established itself as India’s answer to Amazon. Founded in 2007, by two former Amazon employees, Flipkart became India’s first unicorn – a private firm valued at more than US$1 billion – and was celebrated as the bellwether of Indian start-ups after raising US$20 million from US investment firm Tiger Global Management. Online cab-hailing platform Ola, launched in 2010, was another noteworthy Indian start-up, bursting onto the scene to challenge American rival Uber. Ola used discount-led growth to gain market dominance.

Cash-rich Indian corporations such as Tata and Reliance had always been risk-averse and stayed clear of India’s burgeoning online investment opportunities. Even well-entrenched Indian software firms such as Infosys and Wipro were reluctant to finance start-ups, and remain so still.

Modi came to power in 2014, on an expansive promise of development by putting an end to India’s endemic corruption and cronyism. The positive business sentiment at the time was bolstered by initiatives such as “Make in India”, rolled out with a flashy, Wieden+Kennedy-designed ad campaign to encourage companies to manufacture in India, including India online.

With Western tech giants such as Google, Facebook and Amazon setting up their own South Asian subsidiaries, and no major Indian investors in sight, a wave of strategic investment started to pour in around 2015: it was largely Chinese capital that grew stalwarts such as Ola, grocery-delivery firm BigBasket and digital-payment company Paytm.

Chinese corporations such as Alibaba (owner of the South China Morning Post) and Tencent, and Taiwan’s Foxconn started pumping funds into some of India’s biggest consumer internet start-ups, positioning themselves as investors offering the “patient capital” needed to operate loss-making internet ventures.

Mahajan and SJM witnessed this new wave of foreign investment, saying they would keep a “close watch” on the strategic interests of the Chinese.

“There is a change of guard on the investment front,” declared the front page of The Economic Times, India’s biggest financial daily, in 2016.

According to Lunia, Alibaba picking up a 40 per cent stake in Paytm in 2015 changed the course of Chinese tech investment in India, because in 2016, the Indian government announced, out of nowhere and with no warning, that high-value notes – about 86 per cent of the currency in circulation – would no longer be legal tender. This economic shock destroyed the livelihoods of millions, but brought about a huge upswing in cashless payments throughout the country for those with the means – which is to say a smartphone, a luxury 75 per cent of Indians cannot afford.

Analysis | Indians told to boycott Chinese goods after Beijing backs Pakistan on Kashmir

Paytm became the de facto digital wallet in an industry that had more than 200 million subscribers by early 2017. “This demonstrated to the Chinese investors that India is a country where big things can happen,” says Lunia. “Big numbers. Big win.”

A slowdown in domestic growth of consumer-facing internet companies meant deep-pocketed Chinese investors turned to India, the fastest growing internet market in the world. Several big-ticket consumer tech investments from China to India followed. ByteDance’s news app Toutiao invested in Indian news-aggregator start-up Dailyhunt, Chinese food delivery giant Meituan-Dianping propped up Bangalore-based online food-ordering company Swiggy and Didi Chuxing, China’s leading ride-hailing platform, invested in Ola. And in what was reported to be one of the biggest influxes of private capital into India in 2017, Tencent took a stake in Flipkart’s US$1.4 billion fundraiser.

In a memorialised moment in Indian start-up history, when asked about the future capital needs of Paytm, founder Vijay Shekhar Sharma remarked, “Mere paas maa hai, Jack Ma,” wordplay based on a popular Bollywood dialogue from the 1975 film Deewarsuggesting that Alibaba’s Ma (meaning “mother” in Hindi) had his back. Paytm is currently valued at US$16 billion.

The days of cheap Chinese toys and electronics disrupting India’s economy seem of a time long before the Ramlila Ground protests of 2017. As of March this year, Chinese tech investors had pumped an estimated US$4 billion into Indian start-ups, according to a study published by Gateway House, a Mumbai-based think tank. If one were to include tech acquisition and investments by Chinese subsidiaries in Hong Kong and Singapore, the study’s estimates of that figure shoot up to more than US$8 billion, an unprecedented increase from the cumulative US$1.4 billion Chinese investment in Indian tech by 2014.

On May 20, TikTok was mired in yet another controversy, which led to its Google Play Store ratings falling from 4.5 to two stars, as netizens across India swooped in to downrate the app. What started as an insult-heavy roast of TikTokers by a YouTube influencer quickly snowballed into an organised campaign to downvote the app, aided by the #BanTikTokIndia hashtag on Twitter. Unsurprisingly, this Twitter campaign had been preceded in April by #Chinesevirus19, which was intended to hold China accountable for the spread of the coronavirus. Even the Twitter account of Manu Kumar Jain, the India head of Chinese electronics firm Xiaomi, has been bombarded with anti-China messages.

Prateek Waghre, a misinformation researcher who analysed more than 50,000 tweets from the anti-TikTok campaign, says: “We found about 25 per cent of the May 15 batch of tweets came from accounts created in May and can be considered to be an indicator of coordinated activity.” The coordinated behaviour had recurring themes: revenge, the “Chinese virus” and stopping the use of TikTok to affect the Chinese economy.

Deadly border clash prompts renewed calls in India to boycott Chinese tech

The viability of an indigenous economic agenda might be questionable but the boycott campaigns on social media are no longer empty displays of nationalism. There have been ripple effects. In the wake of the backlash, Ji Rong, spokeswoman for the Chinese embassy in India, joined Twitter on March 31 and has been active ever since. “Her activity on Twitter is partly in response to increasing social media anger in India,” says Manoj Kewalramani, a China studies fellow at The Takshashila Institution, in Bangalore. Ji has posted tweet threads such as “Truths You Need To Know” listing points on why China is not to blame, and how it has been helping others.

Waghre says that most of the internally coordinated campaigns are targeted at a domestic Indian audience, but since they are being carried out on Twitter, a global platform, China is likely tracking them. “Considering we are seeing China adopt Russian-esque information pollution operations,” says Waghre, “it is only a matter of time before we see more direct campaigns taking aim at India.”

Despite the outrage, TikTok’s popularity has soared globally since the lockdown, and India has been the biggest driver, with 611 million downloads. Indians spent 5.5 billion hours on TikTok in 2019, and in the same year nearly half of the top 100 apps in India were Chinese. “The calls for banning specific video-sharing apps highlight the tension between technology and our social values,” says Sidharth Chopra, an advocate with India’s Supreme Court.

The lopsided trade balance has long been a source of tension.

“We need to be careful with how we react as India will need capital going forward,” says Kewalramani, who adds that what is required is collaboration in a bubble of trust. “I hope we don’t see India shutting its doors.”

But what comes across as resentment on social media can be traced back to India’s disdain for its own binding dependence on China.

At the end of the day, whatever the rhetoric, consumers speak with their wallets. But customers might not always know what they are buying.

A meme festooned with the logos of prominent Chinese brands was shared with the caption, “Let’s teach them a lesson”. Beneath, the auto-signature read, “Sent from a Xiaomi phone”.