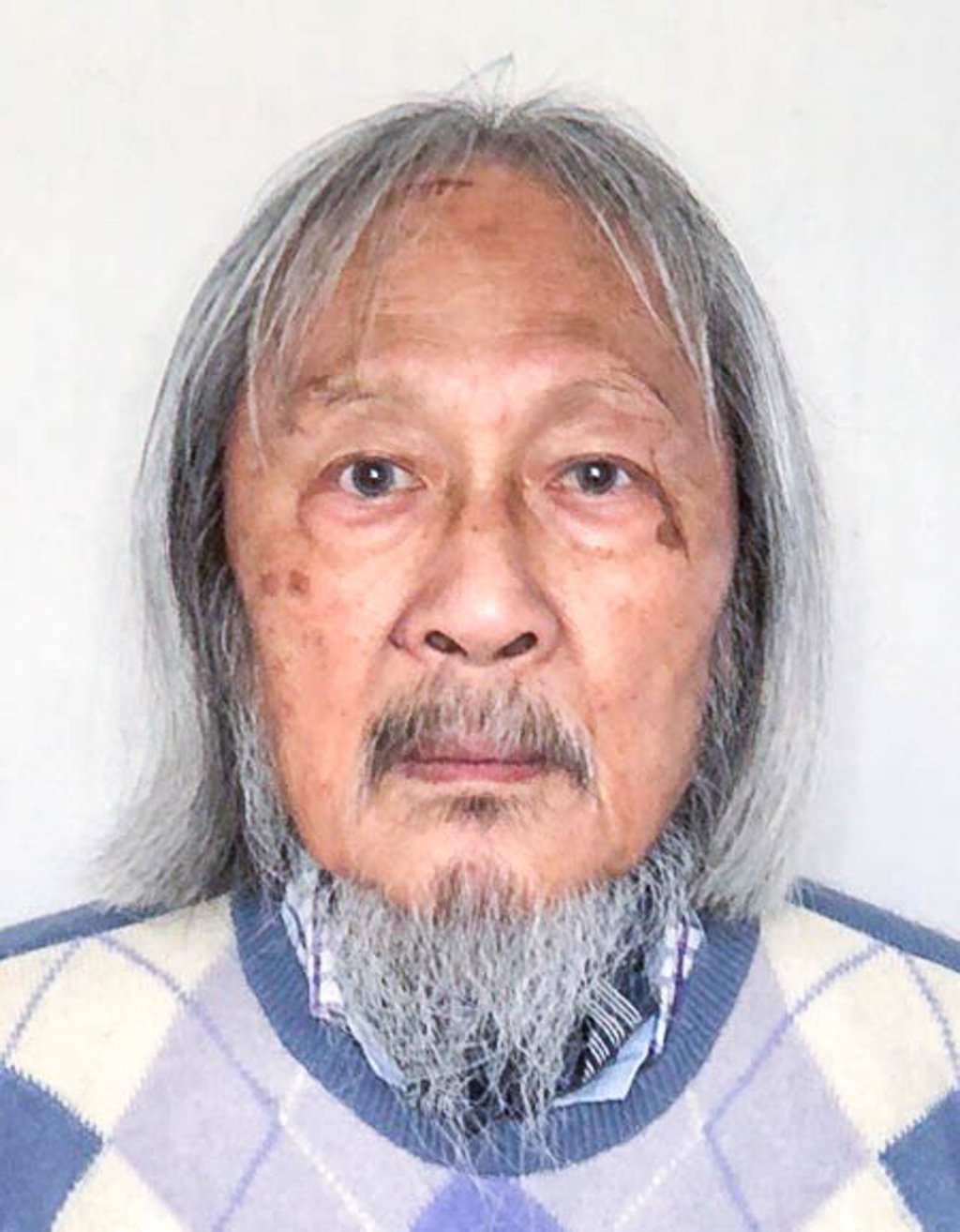

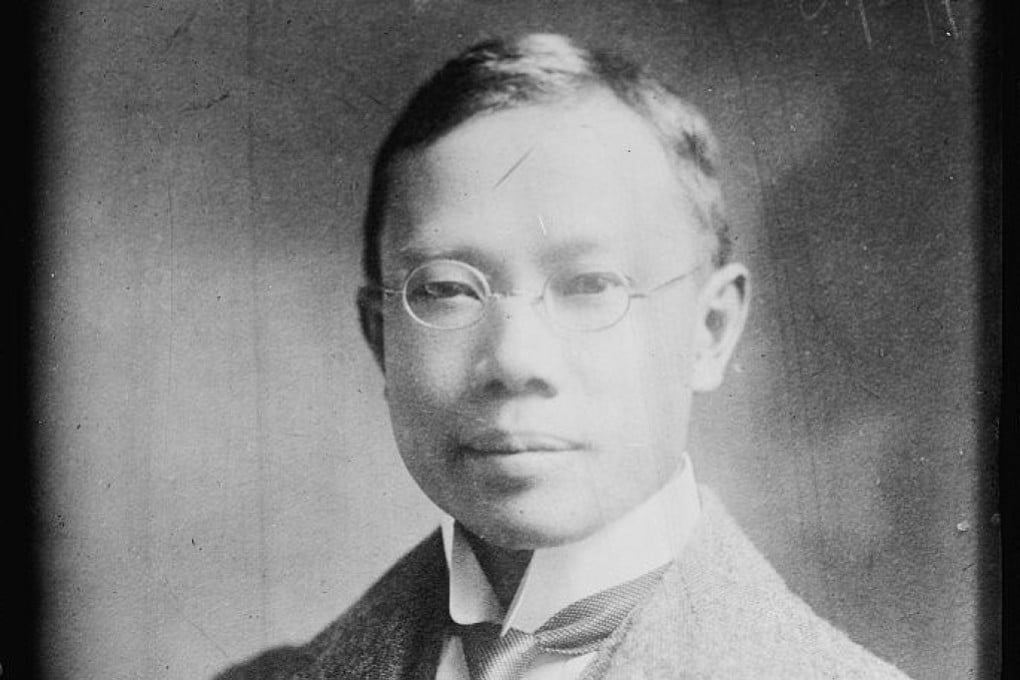

He fought the plague in China and inspired descendants to be doctors like him – the legacy of Wu Lien-teh

In 1910, Dr Wu Lien-teh, born in British Malaya, led a successful fight to suppress a plague outbreak in Harbin, northeast China, with face masks as one of his weapons. Six of his descendants, all doctors, reflect on his legacy and the Covid-19 fight.

Wu, then just 31, led the fight against a deadly pneumonic plague outbreak in Manchuria, northern China. Facing an airborne disease that killed nearly 100 per cent of the more than 60,000 people it infected within a few days, Wu – who was born in British Malaya and educated at Cambridge — was given broad authority not only over local doctors but, police, the military and civil officials. As a result, he was able to end the outbreak within three months of his arrival in the affected area.

The following month, Wu chaired the International Plague Conference in China, a landmark event attended by leading disease experts from 11 nations. In 1935, he was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Medicine.

But beyond public-health practices, Wu also bestowed a professional family tree of sorts – medical descendants spanning four continents, among them leading experts in pathology, virology, radiology and emergency medicine, who are now pleading for enhanced masking policies worldwide, and heightened medical and scientific cooperation across borders. The fate of the world, they believe, depends upon it.

Here are six of their stories.