Inspired by China, Yves Saint Laurent launched the perfume Opium – and got away with it

In 1977, the French fashion house transformed the worlds of fashion and perfume with the release of its latest fragrance, scandalising society, and making hundreds of millions of dollars in the process. It could never have happened today

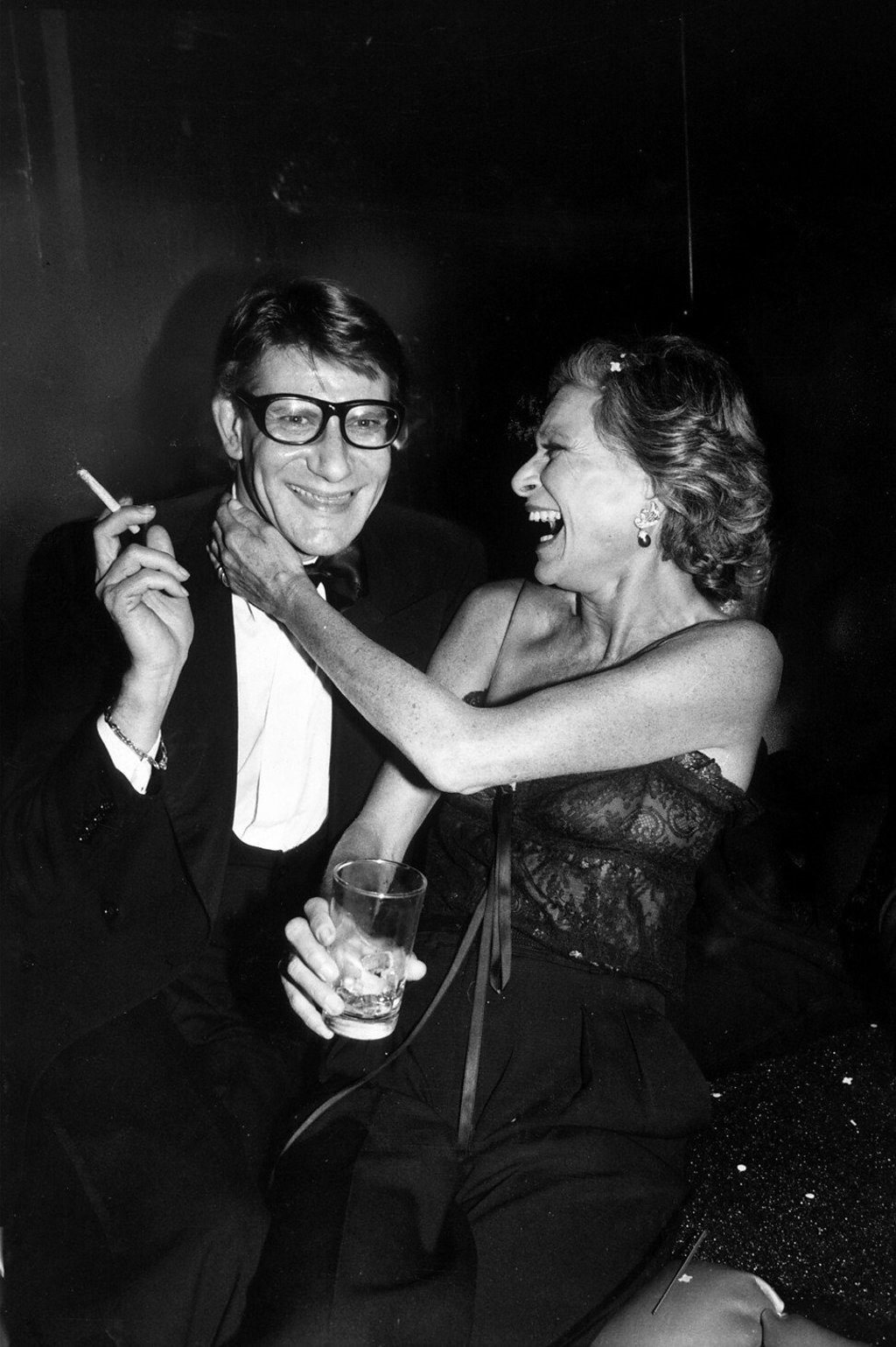

Coral-red paper lanterns lit the way aboard the four-masted Peking, berthed in New York’s harbour. Festooned with banners, hand-painted parasols, thousands of white cattleya orchids and a 450kg bronze Buddha, the ship had been redecorated for that September evening in 1978 to celebrate the American launch of the Yves Saint Laurent perfume Opium.

The launch in Paris the previous autumn was more low-key, but sales far exceeded expectations. Stores sold out immediately, endured long waits to restock, and had posters torn down as souvenirs.

While Opium had achieved higher European sales in the month before Christmas 1977 than Chanel No. 5 did all year, the American launch was stratospheric. Priced above high-end top-sellers at US$100 an ounce, it was the biggest opening that major American department stores such as Saks Fifth Avenue and Bloomingdale’s had ever seen.

Opium converted the Yves Saint Laurent brand into an empire, transforming perfume, and fashion at large, by changing the potency of fragrances, how they were marketed and named, and driving a wave of designer scents that would ultimately dominate a fashion house’s revenue.

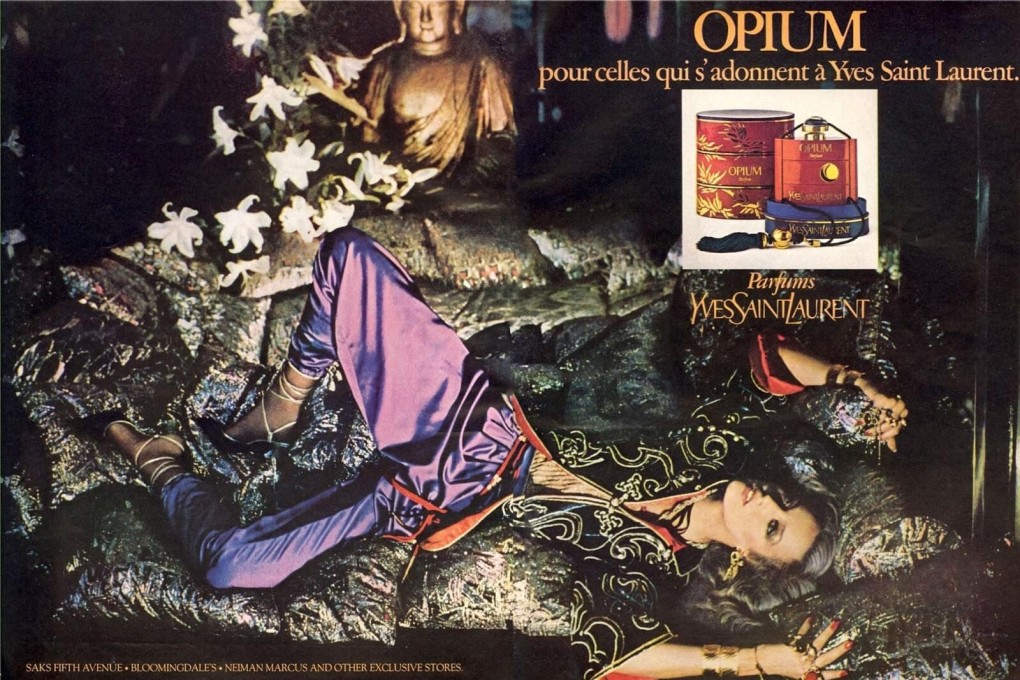

The original Opium advert, shot by Helmut Newton in Saint Laurent’s Paris apartment and styled by the designer himself, featured Texan model Jerry Hall reclining on a black lamé sofa in front of a golden, Ming-dynasty Buddha statue and bouquets of white lilies. Wearing an embroidered oriental blouse, shiny purple satin harem trousers and strappy gold stilettos, Hall – who had just left Bryan Ferry for Mick Jagger – offers an expression of languor and pleasure.

A second version of the ad showed Hall from the waist up, one hand gripping the armrest of the sofa, the other in her hair, eyes closed and lips slightly parted. The tagline: “For those addicted to Yves Saint Laurent.”