Burton Holmes helped shape America’s view of China in the early 20th century – he didn’t always do it justice

- Burton Holmes, the celebrity pioneer of travelogues, gave huge American audiences their first glimpse of China, passing along his prejudices and inaccuracies in the process

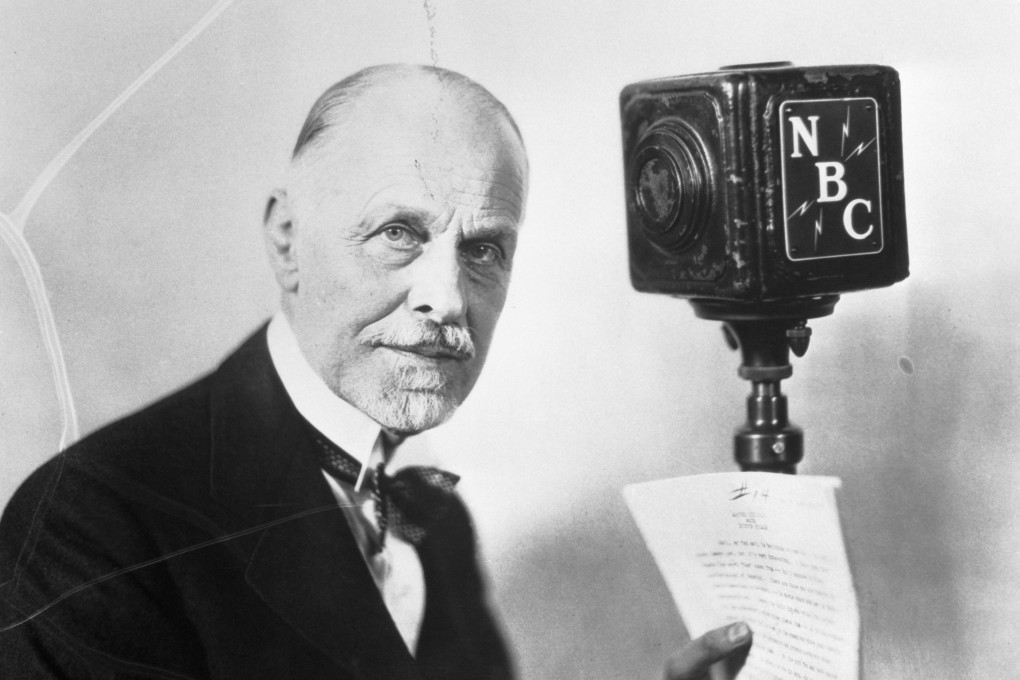

“To travel is to possess the world,” wrote Burton Holmes in many an admirer’s autograph album during his long career as a premier travel lecturer. Between 1892 and 1952, Holmes journeyed overseas most summers and in the winters recounted his travels in front of full houses across the United States, giving about 8,000 lectures in his lifetime.

Holmes met his own travel expenses, but earned about US$5 million throughout his career – about US$80 million in today’s money – according to his biographer, Genoa Caldwell. He owned a two-storey apartment overlooking New York’s Central Park, a many-roomed mansion in California, and hobnobbed with the Hollywood elite.

“He was the most famous non-movie star and non-politician in America of his day,” says Patrick Montgomery, who owns Holmes’ film archive and licenses the footage for use in documentaries.

Often called “the greatest traveller of his time”, Holmes beguiled the moneyed classes of the more cosmopolitan coastal cities with places most of them would never see, and helped to form the opinions of five generations of Americans. These included their ideas of China, although what Holmes had to tell them was limited, often unimaginative, and at times entirely misleading.

Holmes may not have said that the Great Wall could be seen from space, but much that he did say was no less inaccurate.