The pearl fishing industry in Broome, Western Australia, boomed on the backs and blood of slaves plucked from Indigenous communities and, later, Asia, with many risking, and losing, their lives to enrich their white masters

“Aalingoon came into the bay and lives beneath the sea,” wrote late Indigenous pearl shell carver Aubrey Tigan Galiwa, quoted in Lustre, a 2018 book about the Australian pearling industry.

“He comes out every full moon, when it’s a big tide. As he floats on his back, as he drifts, the scales fall off his back, and turn into goowarn [pearl shells] as they drift down to the seabed below. The tides come in and chuck them everywhere, on the reefs, all around the islands. This way he always gives us more shells. This is a power. This is part of our ceremony.”

In the state of Western Australia, pearls are not just beautiful commodities formed by Pinctada oysters. For Indigenous Australians, they are a gift from the rainbow serpent who controls water and rain, deposited across King Sound inlet just east of Broome, an area about five times larger than Hong Kong Island.

For more than 20 millennia, Indigenous people in this region have harvested Pinctada pearl shells, the oldest evidence of their trade being a fragment of a 22,000-year-old shell discovered in the state some 200km from the coastline.

The first pearls to arrive in the Western world were sold widely in the Roman Empire. At that time, these gemstones had already been used in China as luxurious gifts for at least 2,000 years. When Europeans and white Australians learned of Broome’s pearl riches in the mid-1800s, the town became inundated by money-hungry explorers, who used and abused pearl divers. Poorly cared for and paid a pittance, these workers were exploited for decades.

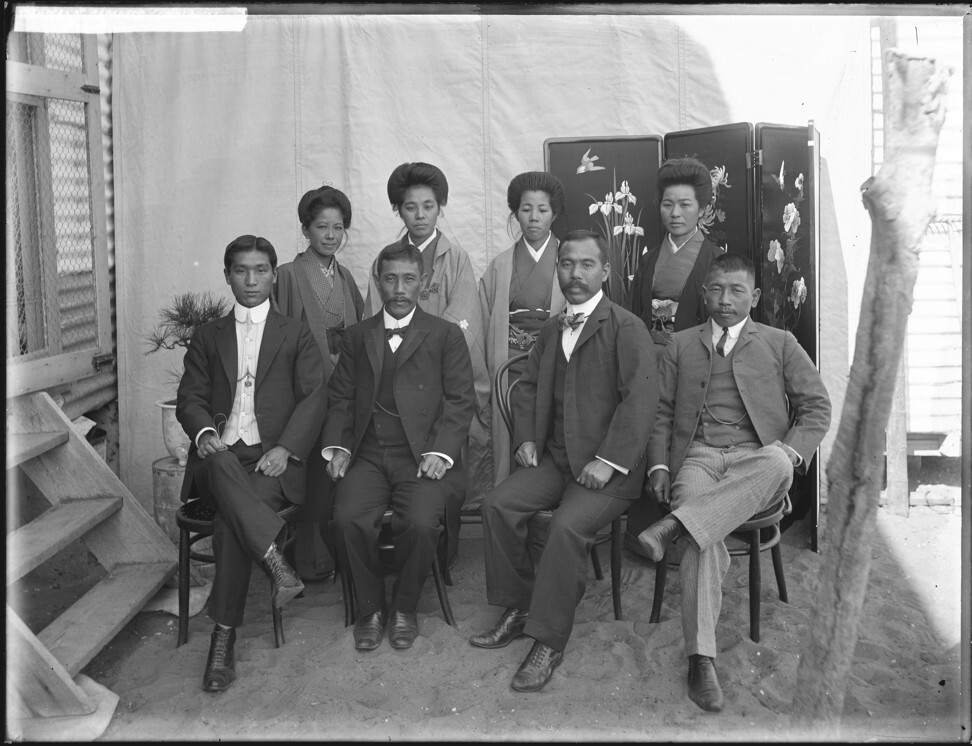

When in 1871 a Western Australian law was introduced to offer some protection to Indigenous workers, pearling bosses chose to look for new divers from China, Japan, Malaysia and the Philippines. By 1910, Western Australia was the world’s biggest pearl producer and, amid the scramble for wealth, pearling bosses flouted state laws, subjecting Indigenous and Asian divers to atrocious working conditions.

Not only were hundreds of these people abused, but an Australian natural resource was pillaged. Pearls take up to four years to develop inside an oyster in the wild, and during this era Australian pearling bosses hoarded all the gems they could find, with no thought for sustainability. Mother Earth, as Indigenous Australians describe the natural environment, was desecrated.

Sarah Yu, one of the authors of Lustre – also presented as an exhibition, touring Western Australian museums for the past five years – possesses both a comprehensive knowledge of Broome’s pearling industry and an intimate connection to its history.

Her husband, Peter Yu, is of mixed Indigenous and Chinese heritage. Born in Broome, he has spent the past 35 years working in the field of Indigenous development and advocacy.

When Asian pearl fishing rivals rioted 100 years ago in Australia

When commercial pearling began in the region 160 years ago, Yu says, Broome was an anarchic frontier town, about 2,000km from the nearest city, the state capital, Perth, rendering it almost invisible to Australia’s lawmakers and enforcers. Until Broome was gazetted as a town, in 1883, the nearest police station was 800km away, at Roebourne.

This isolation emboldened the white Europeans who began the pearling industry. Having identified the profit to be made from Broome’s huge, silver-white Pinctada pearls, they began searching for personnel, says Yu. With few people willing to take on the risky job of pearl diving, the bosses resorted to rounding up young Indigenous men, using violence, threats of physical harm or trickery.

In the latter instances, they would coax Indigenous men onto boats with offers of work close to their communities. Then they would sail hundreds of kilometres, rendering the slaves marooned, unsure of their location, and weeks from home by foot. In Full Fathom Five (1982), Mary Albertus Bain wrote that when these men eventually returned to their communities they found “their families scattered, their women stolen and carried away, some perhaps killed”.

By 1870, pearls were bringing great wealth to Broome, with around 30 pearling boats being operated by about 60 white traders. These men rarely got wet, instead leaving the dangerous work of diving to a collective labour force of up to 300 Indigenous people.

“The Indigenous divers were not being looked after, there was no welfare at all, their bosses could pretty much do whatever they wanted to them,” says Yu. “The white men thought their workers belonged to them. The Indigenous people were really just viewed as assets. They were expendable.”

In the near darkness of the deep ocean, an enemy attacks the body from within. Excess nitrogen, finding no release, causes bubbles in the veins and then the tissues, restricting blood flow and damaging blood vessels. Soon, the body goes into shock.

On resurfacing, confusion, dizziness and fatigue set in, followed by headaches and severe joint pain. For the lucky ones, the symptoms end there; for the less fortunate, paralysis, stroke, heart attack, spinal injury or brain damage await.

This was the deadly, daily reality of decompression sickness (DCS) that Chinese and Indigenous divers faced during the fledgling days of Australia’s pearling industry. From the mid-1800s, a world-leading pearl hub grew up around Broome, supplying buttons to Europe, and continued to flourish on the indentured labour of Asian and Indigenous pearl divers, dozens of whom died making their masters rich.

Morrison quickly backtracked when asked about “blackbirding”, the 19th century practice that saw Indigenous people and Pacific Islanders rounded up, sometimes at gunpoint, and sold as unpaid workers. Such slaves powered Australia’s pearling industry in its formative years in the 1800s, when Indigenous men, women and even children dove deep into the Indian Ocean without safety equipment to retrieve pearl shells.

Bart Pigram was 31 years old when he discovered traces of this exploitation flowed through his bloodline. From a young age, this Indigenous man from Broome had been aware of the local pearling industry’s history, and how white Australia had mistreated his people for more than 200 years.

These Chinese men were sent up to the north of WA to work on farms or on pearl boats because the white people didn’t want to work up there. They knew those jobs were tough and dangerousKaylene Poon, Australian-Chinese historian

He knew some of his ancestors may have been slaves. He knew many of these slaves had died in their forced pursuit of pearls. What he did not know, until six years ago, was that he was related to a notorious pearling slave master.

For generations, Pigram’s family had talked of a white ancestor they called “old Bryan”. Exactly who he was remained elusive. Then in 2014, Pigram began working on Lustre with Yu and a team of other contributors. His research revealed an unpalatable truth. The real name of “old Bryan” was William Bryan, a 19th century pearling boss who had enslaved Indigenous people in Broome.

“It was a big shock, a sort of revelation,” says Pigram, “to know I had connections to someone like that, someone who did those disgusting sorts of things. But it also gives me some really strong identity, to know I’m directly connected to the deepest and darkest stories of pearls here in Broome. It’s a memory of what happened back then that’s always with me now.”

Bryan’s story mirrored those of many other pearling slave masters. In archived newspaper articles uncovered by Pigram, Bryan was reported to have entered Indigenous communities near Broome and taken away dozens of slaves to work on his pearling boats. There was no evidence he was ever punished for this crime.

But an 1889 investigation into one of Bryan’s vessels, the Annie Taylor, did uncover a host of violent offences against Indigenous workers. Bryan was fined for tying four Indigenous crew members to the rigging of the boat. Three of his white colleagues were also fined for assaulting Indigenous workers on the Annie Taylor.

While these punishments were meagre, they were an indication Broome’s pearling bosses were finally being monitored. They were no longer beyond the reach of the authorities. The reason for this was that, in 1871, the Western Australian government had belatedly acknowledged the atrocities occurring in its pearling industry.

They had responded by introducing a law that banned Indigenous women from being used as pearl divers, and aimed to better protect male Indigenous pearl divers, who legally had to be put on paid contracts. With pearling chiefs facing government restrictions and oversight, the taking of Indigenous slaves became riskier. So, in the 1870s, they sought to tap a fresh labour market. Their attention had turned to Asia.

“Then these Chinese men were sent up to the north of WA to work on farms or on pearl boats because the white people didn’t want to work up there,” says Poon. “They knew those jobs were tough and dangerous.”

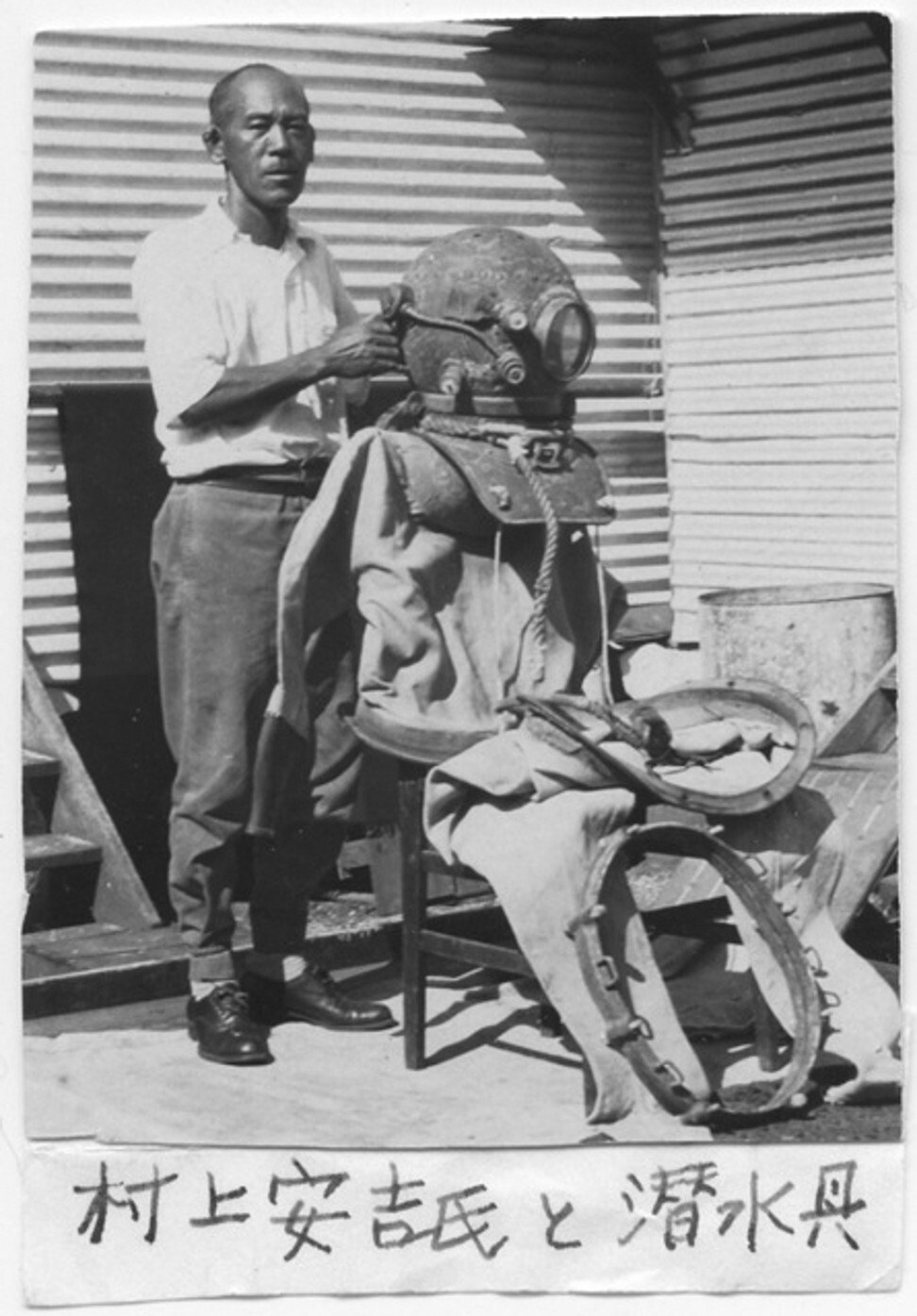

Most of these men became hard-hat divers. Wearing airtight suits and bulky metal diving helmets, they would walk along the seabed searching for pearl shells amid the gloom of deep ocean water. Their survival was in the hands of those on the boat above.

The hard-hat divers were attached to a lifeline and used coded tugs of this rope to send messages to the boat. Their oxygen supply was delivered via a tube from an air compressor and any tangling of this hose could, and sometimes did, prove fatal.

According to Yu, before 1915, due to poor safety protocols, and the “life is cheap” attitude of the pearling bosses, about a third of divers in the Western Australia pearling industry died, a state government investigation found.

Their causes of death varied. Some drowned, others perished from malnourishment, more still died of lung conditions brought on by poor living conditions combined with the physical stress of deep-sea diving. Then there was the dreaded DCS, which every hard-hat diver suffered from. The condition occurs when a diver breathing compressed air rises to the ocean surface and the water pressure around them decreases too quickly, leaving insufficient time for nitrogen to clear from their blood stream.

Out at sea, in one of the world’s most isolated regions, the medical treatment available for pearl divers who were struck down by DCS was grossly inadequate. Some were pulled from the water limp and never regained consciousness.

The poor pay and hazardous working conditions on these boats convinced many Asian divers to escape the industry, says Poon. Some opened restaurants, laundries, gambling houses, tailors or general stores in Broome and throughout Western Australia’s northwest. Others started their own pearling operations. One such was Poon’s great uncle, Henly Fong.

Fong left his family in Guangdong province and moved to Australia’s Northern Territory in 1896, at the age of 20. Soon afterwards he headed to Cossack, south of Broome, having heard of the pearls hidden in its ocean waters. Together with several other Asian men, Fong tried to set up a pearl exploration business, Poon says. Asians, however, were not allowed to own commercial boats, under laws introduced in the 1880s after lobbying by white pearling bosses.

While some Asian entrepreneurs skirted this law by registering their boats in the names of white men, Fong’s venture was blocked by authorities and he had to sell his pearling equipment. He abandoned the industry and became a tailor in Broome, where he married a Japanese woman and remained for the rest of his life, says Poon.

Many Chinese men in northwest Western Australia had two families – one they had left back home and a second in Australia. Typically they partnered with Asian women, and occasionally with Indigenous women. “Because if white women fraternised with Asian men in Broome they could be arrested on vague charges,” says Poon.

This exemplified the animosity towards Asians in Australia at the turn of the 20th century, according to Poon’s cousin, Doug Fong, a retired teacher and amateur historian from Broome. “There was considerable hysteria and fear that the ‘yellow peril’ would overrun white Australian society,” says 82-year-old Fong. “The overriding attitude of the Chinese was work hard, keep your head down, maintain a low profile, stay out of trouble and if facing aggression, turn the other cheek.”

In 1901, this ostracisation of Asians was heightened by the introduction of the now infamous White Australia policy. Under this openly racist legislation, most people of non-European ethnic origin were blocked from migrating to Australia while those already in the country were at risk of deportation. Asians who remained faced harsh new regulations that made it difficult for them to find lucrative employment or run businesses. As a result, Australia’s Asian population fell drastically in the first few decades of the 20th century.

In spite of this hostile environment, Fong’s father, Arthur Tack, refused to budge from Broome, where, by the late 1930s, he was running a general store and a taxi service, and operated two pearling boats. At that time, attitudes towards Asian pearling businesses had softened. Tack’s pearling operation was just taking off when World War II arrived at his doorstep. In 1942, Broome was bombed by the Japanese. Tack and his family fled and upon their return discovered their pearling boats had been destroyed.

After the war, plastic began to dominate the button market, sending Western Australia’s pearling business into a downward spiral. In response, the industry pivoted towards cultured-pearl farms.

That’s why my people need to tell our stories [...] Unless Australians can know these things, how can Australia change?Bart Pigram, Indigenous guide, Narlijia Experiences

Instead of relying on wild pearls, from 1956 onwards Western Australia pearlers started sophisticated operations raising Pinctada oysters to form pearls in controlled conditions. The farms soon came to dominate Western Australia’s pearl trade, creating a safer, more efficient and more sustainable industry. They continue to supply Pinctada pearls to the world today.

Although Broome’s pearling industry has been cleaned up, with divers now aided by cutting-edge technology and safety equipment, its grim history looms large in a nation still attempting to reconcile with its Indigenous people. Australia continues to make steady but slow progress in addressing the historic and ongoing injustices faced by its original inhabitants. The state of Victoria recently announced a landmark “truth-telling” process, intended to acknowledge and counteract these wrongdoings.

These positive developments, however, can be overshadowed when a leader makes a statement as patently false as Morrison’s denial of slavery in Australia.

“Morrison’s comments didn’t surprise me,” says Pigram. “Because that’s how lots of those Australian leaders think. They’ve never been properly educated about what my people went through here [in Broome] or other places. The education system taught them all lies – that when the British arrived, Australia was just ‘terra nullius’ [Latin for ‘land belonging to no one’].”

Pigram relays this message to white Australian tourists who join his Narlijia Experiences tours in Broome. He tells them that Indigenous Australians have traded pearls for more than 20,000 years and that these gemstones are a gift from Aalingoon. He reminds them that thousands of Broome’s pearls were tainted by the blood of Indigenous and Asian divers.

“That’s why my people need to tell our stories,” he says, “to tell about the slavery that happened with pearling here in Broome. That stuff was disgusting. Lots of people died. Unless Australians can know these things, how can Australia change? How can it get better?”