The Canadian professor, philosopher and oracle of 1960s counterculture foresaw humanity’s ‘march backwards into the future’ as we are consumed by our digital landscapes

For much of 2020, as the coronavirus pandemic disrupted our physical reality, equally dangerous pathogens surged unchecked through our digital mediascapes. The technologies that promised to bring the world together have ruptured, exposing an unstable, corruptible core where conspiracy and prejudice thrive. It is a far cry from the enlightened digital utopia the internet was thought to be capable of facilitating early on. Instead, the inverse situation seems far more prevalent.

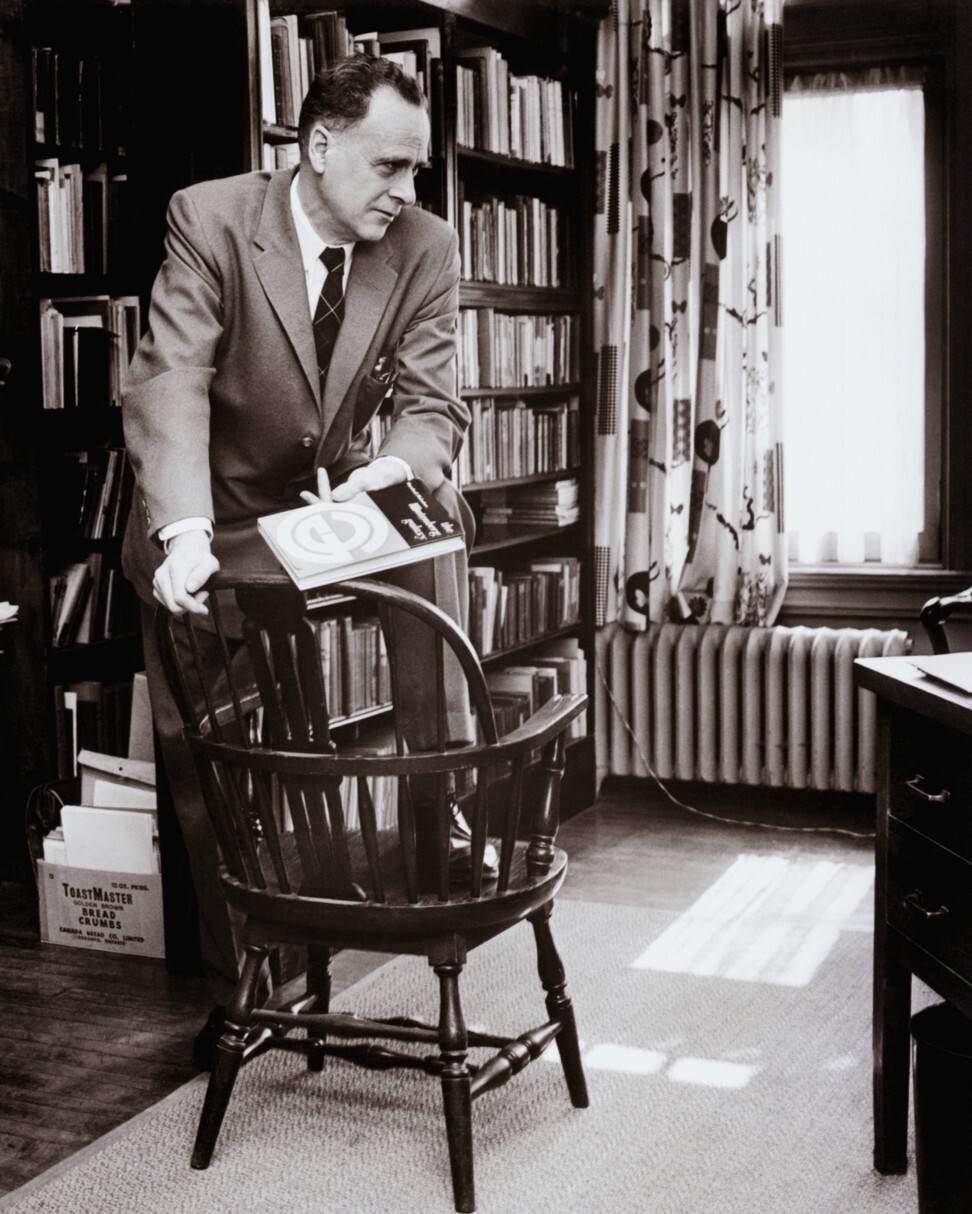

So in 2021, as we attempt to remedy viruses both biological and technological, it could pay to revisit the work of professor and philosopher Marshall McLuhan, the oracle of 1960s counterculture who predicted the dysfunctional state of our current media, despite drawing his last breath in 1980 – a decade before Tim Berners-Lee published the first-ever website.

McLuhan’s work sheds much-needed light on the widespread effects of contemporary media in both the East and the West; reveals a number of fascinating connections to ancient divination text the I Ching (Book of Changes); explains the revival of classical Chinese literature as an effect of our digital world; and opens up startling new perspectives on future communication technologies. And that is just scratching the surface of his legacy.

Now, almost 60 years after his classic works were published, the strait-laced Canadian has left us with as good a road map as any for navigating a 21st century media dominated by Machiavellian algorithms, rampant disinformation and metrics-driven emotional manipulation. As McLuhan himself cautioned, his famously coined “global village” would not be “the place to find ideal peace and harmony”.

“Instead of tending towards a vast Alexandrian library the world has become a computer, an electronic brain,” he wrote about what would have passed for big data in 1962. “And as our senses have gone outside us, Big Brother goes inside.”

As early as 1960 he described the world as “a continually sounding tribal drum, where everybody gets the message all the time. A princess gets married in England and ‘boom boom boom’ go the drums – we all hear about it [ … ] A Hollywood star gets drunk, away go the drums again.”

Sound familiar?

McLuhan’s career as media prophet began at the start of his teaching career with one overriding realisation: that his students were not like him. They spoke a new slang and seemed detached from history, engulfed in a permanent “now”. They had, McLuhan understood with ever-increasing clarity, been transformed by advertising, cinema and the nascent mass medium of television, into human beings of a very different nature than the print-led creatures of the pre-electric age.

One of McLuhan’s favourite metaphors for explaining the effects of media on humanity was the myth of Narcissus, the beautiful hunter hypnotised by the sight of his own image in a pool of water. McLuhan always made sure to point out that, while commonly thought to have fallen in love with himself, Narcissus believed his reflection was somebody else. Likewise, we collectively struggle to see that our media, whether print, TV, the internet, whatever, is also an extension of ourselves.

“We invent new technologies and when we extend ourselves through these things, we also numb ourselves,” says grandson Andrew McLuhan, who currently splits his time between an upholstery business and his role as director of the virtual McLuhan Institute. “A lot of what Marshall was doing was trying to wake us up to what he called our somnambulist state, our state of sleepwalking.”

In the course of this intellectual quest, it was more than a little remarkable that McLuhan – an outwardly “square” professor from Canada’s prairies with a fondness for James Joyce – became an icon for the “turn-on tune-in drop-out” generation of Timothy Leary acolytes. He exchanged ideas with John Lennon and Yoko Ono, was entertained by Canadian prime minister Pierre Trudeau, dined with Andy Warhol, and posed for Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar.

Throughout, he remained divisive. On one side “the world’s first pop philosopher”, “the high priest of pop culture”, and on the other, “that nut professor in Canada”. (The 2021 equivalent might be if Noam Chomsky or Slavoj Zizek suddenly matched a Kardashian’s number of Instagram followers.)

As McLuhan reminded us, what really matters is not what we consume, but how various media change and transform us. “We shape our tools and then they shape us. The content or message of any particular medium has about as much importance as the stencilling on the casing of an atomic bomb.”

The timescale for McLuhan’s research into media encompassed the entire history of humanity, spanning a huge swathe of subjects: quantum physics, advertising, anthropology, TV, epic poetry, painting, movies, the Chinese ideogram, American rock ’n’ roll. His definition of media was just as broad: “It includes any technology whatever that creates extensions of the human body and senses,” he told Playboy magazine in 1969, “from clothing to the computer.”

Derrick de Kerckhove, guest professor at the Polytechnic Institute of Milan, is a former student and friend of McLuhan. “He was one of the most reluctant – but real – prophets that I have ever met. He also said that anyone who wants to be a good prophet should never predict anything that hasn’t already happened.”

For McLuhan, the future could be either cataclysmic or transcendent, and by describing himself as “an apocalyptic” he was freighting his message with possibilities both visionary and portentous. On one hand, he saw “the threshold of a liberating and exhilarating world” in which “man’s consciousness can be [ … ] enabled to roam the cosmos”. On the other, he acknowledged the “profound pain” of living in his electronic age.

“We are now losing that extraordinary power because we are trusting our cellphones to do our thinking for us,” says de Kerckhove. “He really predicted the time we’re living through right now [ … ] He predicted the chaos.”

Herbert Marshall McLuhan was born in Edmonton, Alberta, in 1911, the same year as Ronald Reagan, Ginger Rogers, Tennessee Williams and L. Ron Hubbard. He was raised in Winnipeg, Manitoba, by a salesman father who occasionally played the fiddle and a theatrical mother, Elsie, who impressed on McLuhan a strong sense that his destiny lay in the cosmopolitan, highbrow literary wonderlands outside small-town Canada.

McLuhan memorised long passages of poetry, encouraged by Elsie to associate literature with a love of the spoken word. The difference between reading silently alone and sharing culture through speech was central to the theories on which McLuhan would build his name.

By the time he graduated with a PhD from Cambridge University in 1943 – to add to his two bachelor’s and two master’s degrees – he had not only devoured huge chunks of knowledge and followed his mother’s prescription for travel, but had also married a young Texan actress, Corinne.

The ground for their matrimony was laid by Elsie, who had placed herself in the social orbit of the Pasadena Playhouse, near Southern California’s Huntington Library, where McLuhan could source rare tomes for his Cambridge PhD thesis on 16th century satirist and pamphleteer Thomas Nashe.

During the 1940s, the hyper-bookish scholar matured into the avant-garde professor, whose journey into full-time academia took him from St Louis University through Assumption College in Windsor, Ontario, to the University of Toronto, where McLuhan remained from 1946 until the end of his career.

Inspired by the towering intellects he had encountered at Cambridge, McLuhan would wrap his own literary obsessions, from Nashe to modernist heavyweights including Joyce and Ezra Pound, into a roiling brew of science, philosophy and culture that would produce his overarching theory of everything: that media radically alter humanity far more than any message those media contain.

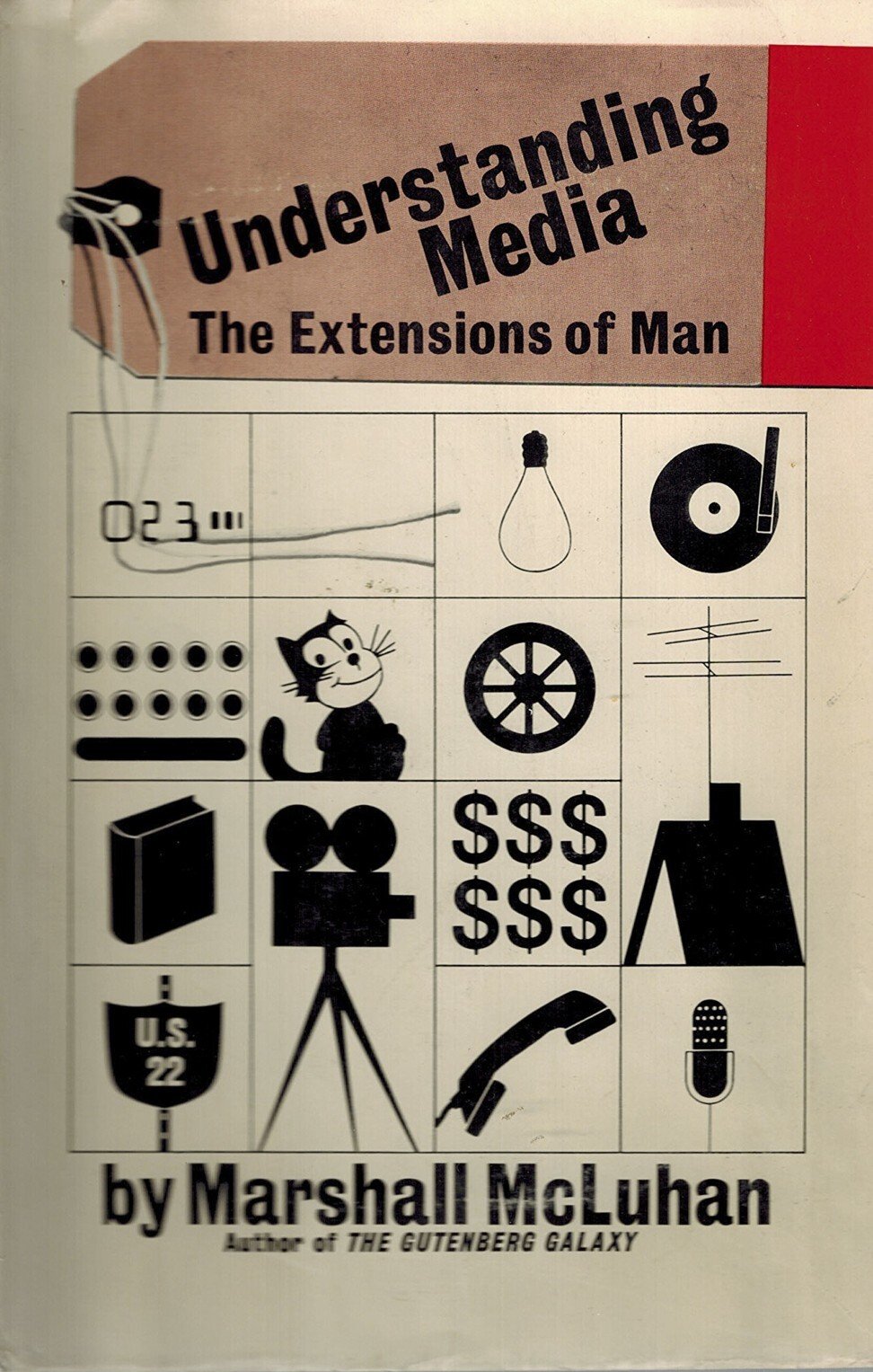

McLuhan’s legendary phrase, “the medium is the message”, was first used in 1958, and his two books, The Gutenberg Galaxy (1962) and Understanding Media (1964), fleshed out a vision that would set the stage for his ideas to light up the late-60s with such intensity.

With fitting irony, the arch-analyst of media and advertising became a product himself. McLuhan’s name was bandied around like a household cleaning brand, driven by a combination of marketing and word of mouth, even though hardly anyone had the faintest clue what he was actually talking about.

If it is a stretch to endow McLuhan “fifth Beatle” status, the band can be viewed as a quartet of extra McLuhans. Author Thomas MacFarlane makes the case in his 2012 book, The Beatles and McLuhan, that “The Beatles would come to resonate with – and ultimately reflect – Marshall McLuhan’s ideas.”

The McLuhan “brandwagon” – replete with bumper stickers that read “Marshall McLuhan writes books” – was assembled and fuelled by a pair of media impresarios: consulting firm gurus Howard Gossage and Gerry Feigen. They had been so impressed by Understanding Media that they decided to package the author and sell him to the world, starting with the 1965 McLuhan Festival, and proceeding through magazine features and a string of delightfully off-kilter TV appearances.

In the electric age, we wear all mankind as our skinMarshall McLuhan

By no coincidence, the impresarios behind The Monkees (Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider) turned out to be big fans of McLuhan’s work. Jack Nicholson, about to hit the big time with Easy Rider (1969), has said that he and Rafelson co-wrote the script for satirical Monkees movie Head (1968), “based on the theories of Marshall McLuhan”. The film – which tries a little too hard to make cinematic art from the “mosaic world of all-at-onceness” described by McLuhan – is a notable addition to the freaky annals of cult psychedelia.

McLuhan, the polished small-screen performer, can be witnessed today at the height of his powers on a medium he mastered, through a medium he predicted: on TV, via the internet. Digitally preserved in monochrome among the global celebrities who also defined the mid-1960s – whether Mick Jagger mastering the feral grammar of rock ’n’ roll in an early version of Satisfaction or a neatly suited Bruce Lee blurring fist and foot into a lightning display of martial artistry for a Hollywood screen test – McLuhan lights up an era he seems to have gatecrashed by accident.

Long past the first flush of youth, he crackles eloquently back at us in low-definition digitised video, leaving a phosphorus trail of pronouncements to consider:

“In the electric age, we wear all mankind as our skin,” or, “We march backwards into the future.”

McLuhan’s stock of memorable phrases is inexhaustible. “He had this mind which was just constantly in motion,” says Andrew McLuhan. “He would famously call people at two or three in the morning to share some exciting discovery with them. And they were like, ‘Jeez, Marshall, do you know what time it is?’ He was always on.”

McLuhan made a virtue of his strait-laced, establishment appearance by coupling it with easy-going charm and intellectual pyrotechnics. Dressed down in standard-issue, smart-casual jacket and a clip-on tie, McLuhan held his own as a pop icon, elegantly duked it out in small-screen debates with literary firebrands such as Norman Mailer and Truman Capote and snagged a late-career cameo in Woody Allen’s 1977 movie Annie Hall, as himself.

It was the fate of any TV host to become a deer in the McLuhan headlights. The confusion is there for all to see, on YouTube. Chat show legend Dick Cavett compared McLuhan’s intellectual peacockery to an explosion at a munitions factory: “Ideas go off in all directions when Marshall McLuhan is here.”

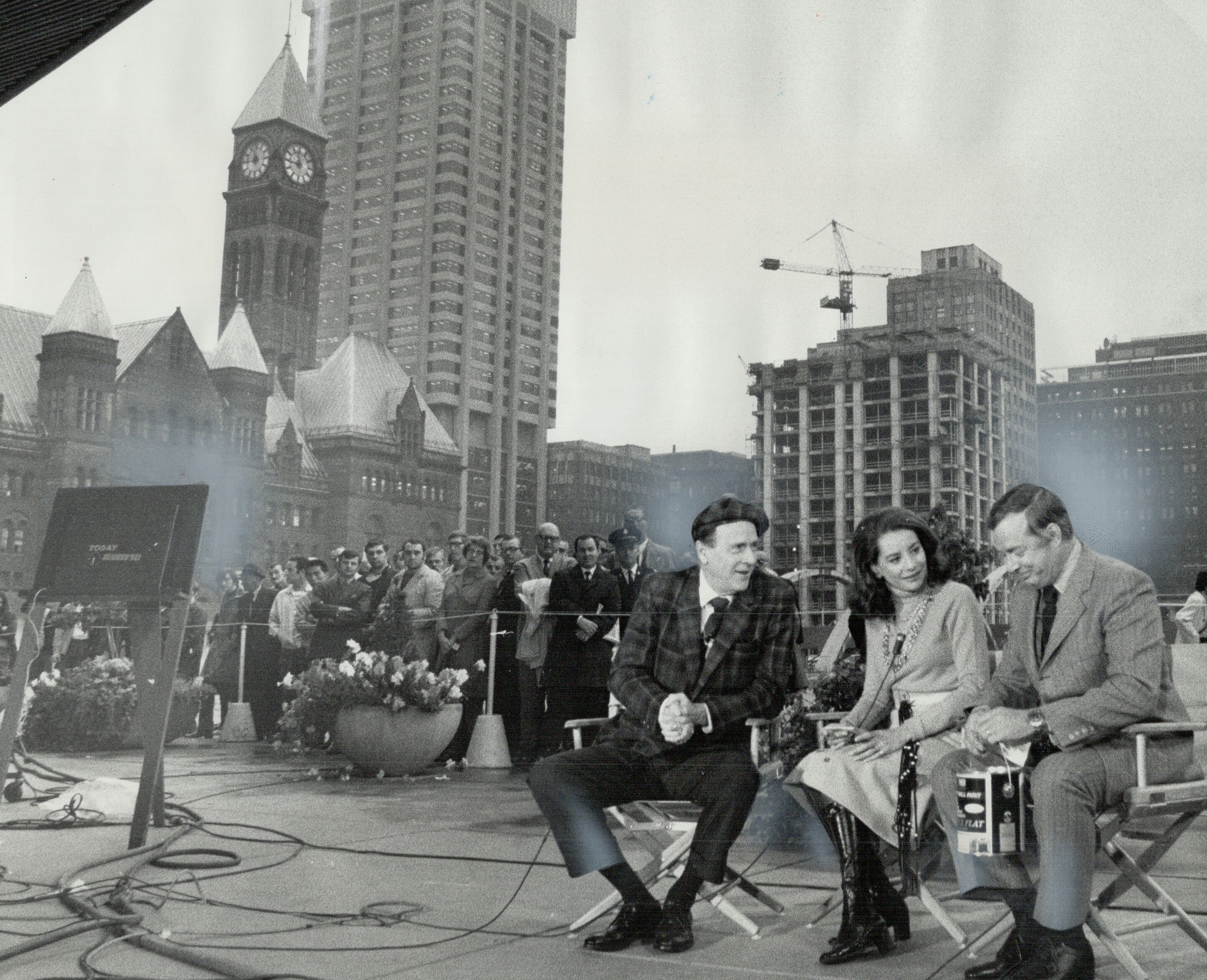

When, in 1970, McLuhan tells Today Show host Barbara Walters, “It’s people who are sent, not the message”, she can only respond, “I must say, you send me!” before retreating to the safety of a sponsored plug for “Sears interior latex paint”. When McLuhan charmingly poleaxes a chat show audience with an allusion to Alice in Wonderland – “The Cheshire Cat that came on smiling minus its body: that’s us!” – the reaction is a nonplussed silence pebble-dashed with nervous giggles.

“Marshall liked to say that anyone who thinks there’s a difference between education and entertainment doesn’t know the first thing about either,” says Andrew McLuhan. “So he would loosen up his audience with a few jokes and then he would dig into his material. And when he felt he was maybe losing them, or they were getting too serious, he just started cracking jokes and loosening them up again.

“He had some pretty crazy ideas but you have to understand that he considered himself an explorer. He invented his aphoristic style not so much to be controversial, but to test and to probe – to poke and prod at things and see what they reveal.”

McLuhan’s method was essentially a series of questions, not a set of prescriptions. His work can be seen as an ongoing dialogue to uncover the signal within the noise and try to understand the engulfing power of the media maelstrom. Among the methods of inquiry he pursued, serendipity and chance had a role to play, and here McLuhan’s legacy intersects with one of the cornerstones of Chinese philosophical literature: the I Ching.

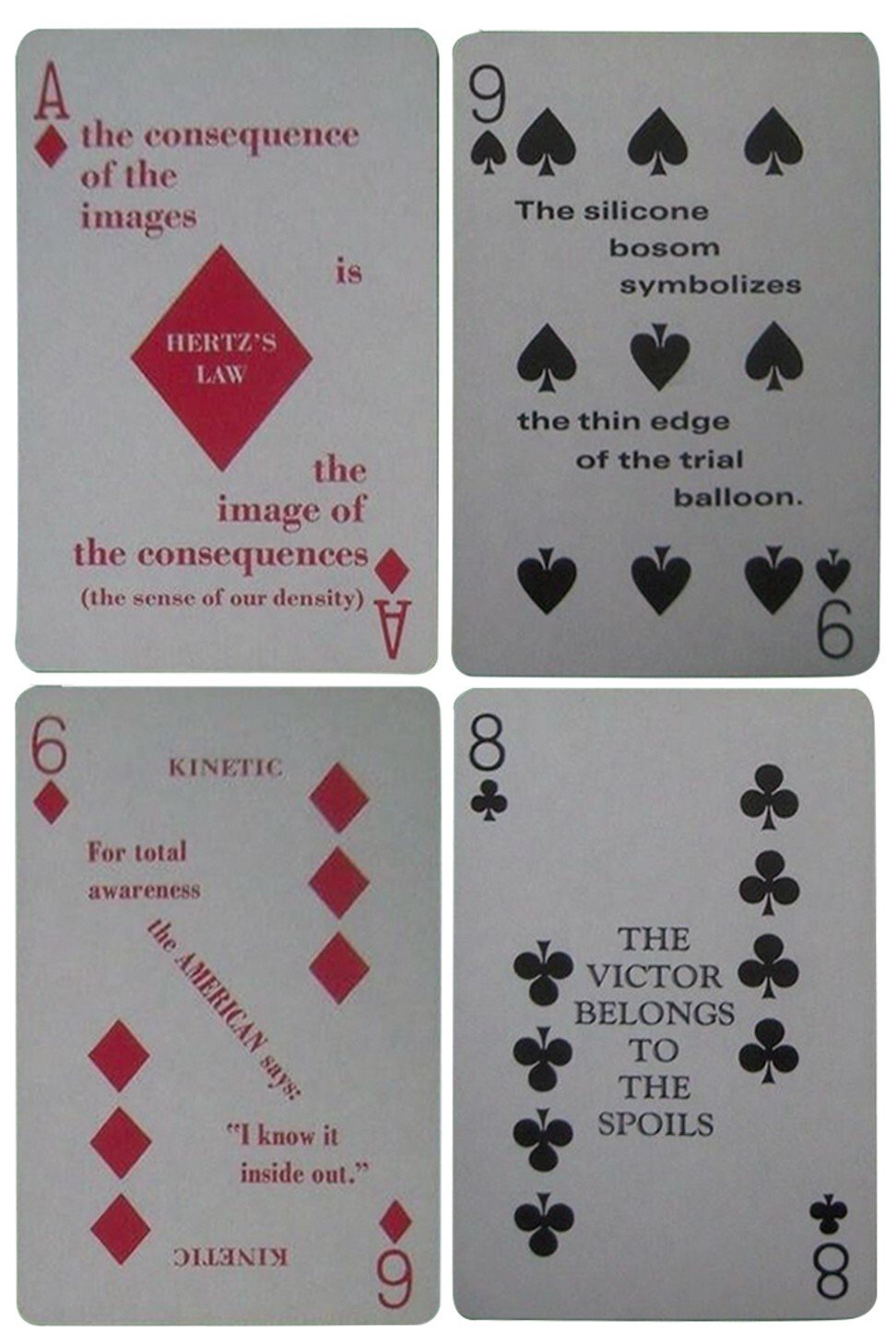

In 1969, McLuhan created a deck of DEW (Distant Early Warning) Line playing cards, co-designed with artist and scholar Harley Parker, and inspired by the DEW Line radio stations built in North America to detect nuclear attack. For McLuhan, radar was a metaphor for the ability to detect media effects.

Like the use of hexagrams and yarrow stalks described in the I Ching, these playing cards – drawn randomly and printed with phrases like “a man wrapped up in himself makes a small package” and “the victor belongs to the spoils” – were a way to get a quick hit of inspiration and to unclog mental blocks.

“When you re-approach a difficult problem with a well-lubricated mental apparatus, chances are you will suddenly see a solution,” says Peter Zhang, professor of communication studies at Grand Valley State University, in Michigan. “There’s a methodology behind using this deck of cards to get out of a difficult situation – McLuhan would call it probing. He used the metaphor of cracking a safe. All of a sudden, unexpectedly, the lock is opened and the problem melts away.”

McLuhan explicitly referred to the I Ching a few times, says Zhang. “The connection can be felt strongly in Laws of Media, in which he summarises the fourfold transformation brought about by each medium.”

Published posthumously in 1988, and written in collaboration with his son and assistant Eric (Andrew’s father), Laws of Media offered up a simple device for considering the effects of any medium. McLuhan named this device the “tetrad”, and it’s essentially a group of four questions: what does any medium retrieve, enhance, obsolesce and reverse into?

He found that “everything man makes and does, every process, every style, every artefact, every poem, song, painting, gimmick, gadget, theory, technology – every product of human effort – manifested the same four dimensions”.

As China increasingly and deliberately distinguishes itself and its own history from the history of the West, which is entirely appropriate, this turns out to be an effect of digital technologyMark Stahlman, president of the Centre for the Study of Digital Life

For example, the internet could be said to retrieve community, enhance communication, obsolesce distance and reverse into isolation. For Zhang, the “reversal” quadrant of the McLuhan tetrad is especially interesting in connection with the I Ching. “People who are familiar with Chinese thought see similar processes in the cosmos,” he explains. “Anything pushed to an extreme suddenly flips or reverses its course.”

Mark Stahlman – president of the Centre for the Study of Digital Life and, according to Forbes, a “tech-trend prophet” – offers a fascinating take on how McLuhan’s tetrad provides insight into the effects of digital technology in the East. “The retrieval quadrant for the computer, as published in Laws of Media is ‘perfect memory – total and exact’,” says Stahlman.

“And this is already showing up in significant ways in China. The Central Party School in Beijing has for the past five years, at least, been quite deliberately teaching Chinese classics to cadres that are moving up through the CPC [Communist Party of China]. As it turns out Xi Jinping is himself an amateur scholar of Chinese classics and Xi Jinping’s wife [Peng Liyuan] is the most famous folk singer of classic Chinese songs. And this is memory.

“So, as China increasingly and deliberately distinguishes itself and its own history from the history of the West, which is entirely appropriate, this turns out to be an effect of digital technology.”

Just as McLuhan anticipated, another consequence of digital media in both the East and the West has been an increase in widespread surveillance. Former McLuhan student de Kerckhove elaborates: “That’s what’s happening to us. The digital transformation doesn’t give a hoot about privacy. The difference between the Chinese and the Americans is that while they use similar techniques, the foundation of the Chinese use of social credit is to ensure social order and harmony, whereas – as Shoshana Zuboff brilliantly explains in her book, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism [2018] – the same technologies are used [in the West] to make more money.

“That’s the very big difference between the East and the West. The East is community-oriented and the West is strongly individualised. In a Chinese context, it makes perfect sense to be under permanent surveillance.”

The way to win back control over some of the capacity we have surrendered, he suggests, may involve some darker arts.

“People will grab control of Alexa, of Siri, or Bixby – all these digital assistants – and all the data that constitute our digital unconscious will be connected. That information suddenly becomes useful as a life-log, as a counsellor, as a note-taker – I call that the ‘digital twin’. That creature becomes our centre of decisions, nourished by years of literacy but now externalised. The sooner we can kidnap Alexa and make her work for us, the better we’ll be.”

Whether the corporate giants of big technology are sabotaged on a grand scale, Robin Hood-style, by acts of well-intentioned hostage-taking, the effects of media still in their infancy are likely to be momentous. Again, McLuhan may turn out to be indispensable as we try to figure out how these effects will manifest themselves. He was perhaps nudging us in the right direction with his idea that electronic media leave us in a discarnate state, “without a body”.

“McLuhan foresaw that electronic media gave humans the quality of a disembodied, angel-like spirit, which happens to us right now when we literally resettle to social media or video games and operate our digital selves,” says Andrey Miroshnichenko, a Canada-based McLuhan scholar.

“Electronic media cancelled the physical time and space limitation for humans to be present at events. Digital media advanced this new quality of human beings even more, they make time elastic, which is impossible in physical reality. In video games, a player can slow down, stop, reverse, repeat time. Resurrection becomes everyday routine for video game players, who save and restart their digital selves, and for social media users, who can delete and restore their profiles.”

Future media and technologies – including what happens when virtual reality and augmented reality, for example, are combined with accelerated computational power – could amplify this angelic tendency, says Miroshnichenko, and bring about a new kind of “augmented humanity”. “Now we are about to totally live inside our latest medium. Almost all our activities are already there. Humankind is resettling from biological bodies into the digital body.”

How, ultimately, media and technology affect us all – and the degree to which human nature is remoulded and redefined by our ‘tools’ – is open to debate. And that’s McLuhan’s point: “The central purpose of all my work is to convey this message,” he told Playboy magazine. “That by understanding media as they extend man, we gain a measure of control over them.”

Whether we pull back from our current media immersion, or plough ahead with our algorithm-fed addictions, the die has already been cast. Strict technological determinists would argue that all efforts to resist our media are futile in the long run: our tools will always set a course we are compelled to follow.

For de Kerckhove, McLuhan’s message was clear – lunge for the off-switch: “He said, ‘Turn it off, turn it all off – turn off the TV, turn off the radio, turn off these media because they’re literally swallowing you alive!’ But he said we can’t stop these things. You have to grab that beast by somewhere – it is a transformation, not just of business, but of people, of society, of politics, of everything.”

The man himself may have the best advice of all, delivered in a 1960 report for educational broadcasters: “Instead of scurrying into a corner and wailing about what media are doing to us, one should charge straight ahead,” McLuhan counselled, “and kick them in the electrodes.”