She memorised IBM typewriter codes for 5,400 Chinese characters but couldn’t save tech giant’s ill-fated machine

- Lois Lew, 95, recalls how her incredible memory helped make IBM’s revolutionary typewriter front-page news in the 1940s as she travelled the US and China to show it off

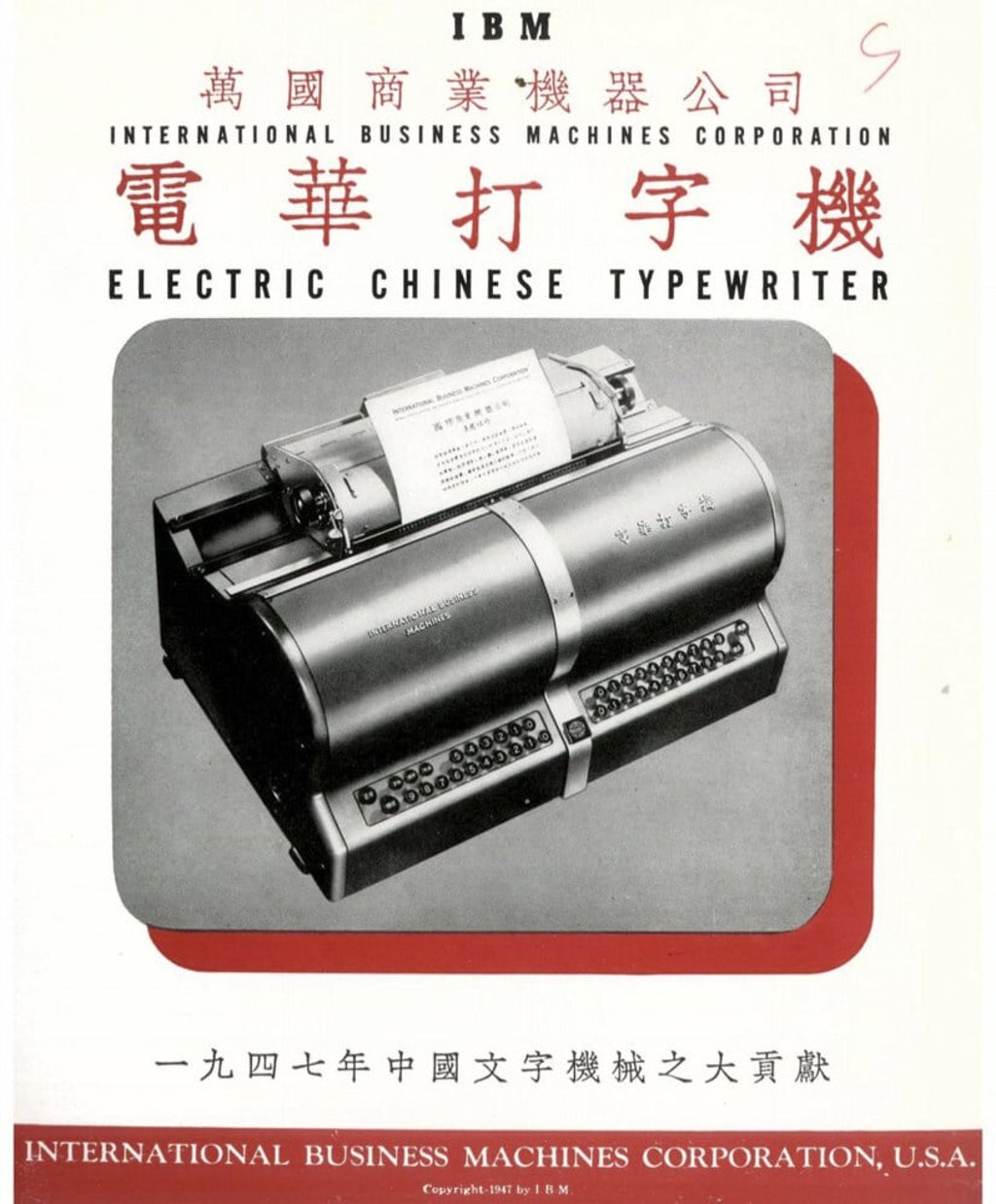

I had seen this woman before. Many times now. I was certain of it. But who was she? In a film from 1947, she is operating an electric Chinese typewriter, the first of its kind, manufactured by IBM. Semi-circled by journalists, and a nervous-looking middle-aged Chinese man – Kao Chung-chin, the engineer who invented the machine – she radiates a smile as she pulls a sheet of paper from the device. Kao is biting his lip, his eyes darting between the crowd and the typist.

As I thought, I had indeed encountered the typist in my research, in glossy IBM brochures and on the cover of Chinese magazines. Who was she? Why did she appear so frequently, so prominently, in the history of IBM’s effort to electrify the Chinese language?

The IBM Chinese typewriter was a formidable machine – not something just anyone could handle with the skill of the young typist in the film. On the keyboard affixed to the hulking, gunmetal grey chassis, 36 keys were divided into four banks: 0 to 5; 0 to 9; 0 to 9; and 0 to 9. With just these 36 keys, the machine was capable of producing up to 5,400 Chinese characters, wielding a language that was infinitely more difficult to mechanise than English or other Western writing systems.

To type a character, one depressed four keys – one from each bank – more or less simultaneously, compared by one observer to playing a chord on the piano. Just as the film explained, “If you want to type word number 4862 you would press four-eight-six-two and the machine would type the right character.”

Each four-digit code corresponded with a character etched on a revolving drum inside the typewriter. Spinning at a speed of one revolution per second, the drum measured 18cm in diameter and 28cm in length. Its surface was etched with 5,400 Chinese characters, letters of the English alphabet, punctuation marks, numerals and a handful of other symbols.

How was the typist in the film able to pull off such a remarkable feat of memory? Certainly, there are a host of professionals who, in the course of their daily work, are able to wield an impressive array of codes – telegraph operators, emergency responders, court stenographers, musicians, police officers, grocery store clerks. But none of them have to memorise thousands of ciphers or codes. This young woman was a virtuoso.