Foreign musicians in China on the halcyon days

- For many Western musicians, China in the early 21st century was a freewheeling land of opportunity – and massive, mind-bending audiences

We were summoned from the backstage tent by an anxious organiser. “Smiling Knives yuedui,” she said, scanning her clipboard and using the word “band” in Chinese, ushering us along with a curt, “You go.”

Putting down our complimentary drinks, we readied our instruments and were guided onstage, which was actually a huge ship moored in the Pearl River estuary. British frontman Gary Hurlstone was followed by American horn player Greg Merrell, Canadian percussionist Craig Anderson and myself, the other Briton, bass in hand.

“Three practices were not enough for this,” I thought, casting my eyes across the gathered mass of eager faces, where nothing but a sandbar had been during a soundcheck earlier. From our elevated vantage point it looked like half of Zhuhai had turned out for this government-sponsored, free concert on New Year’s Eve 2014.

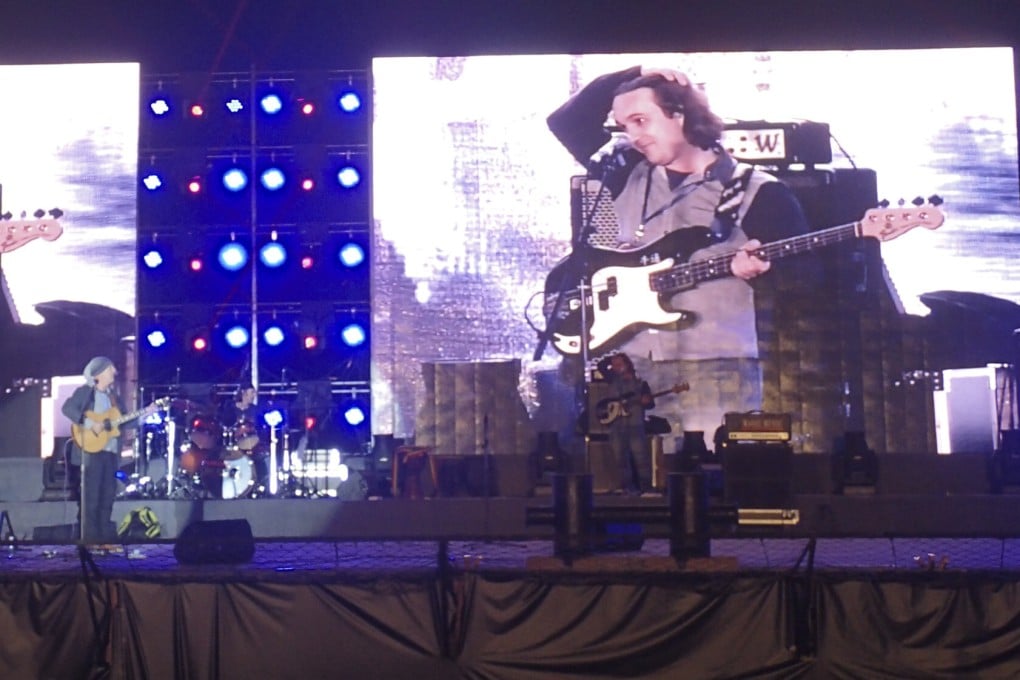

An announcer introduced our band of China-based foreigners as if it were Lollapalooza, like we were an international act that had been flown in for the occasion. After a few unsteady bars of Hurlstone’s The Zen Kick, I glanced over at drummer Anderson to make sure he was finding the groove, conscious that the band had been so quickly pieced together for the event. My nerves twitched again, however, when I looked back to see my image beamed across two giant screens flanking the stage.

Surreal? Yes. Ridiculous? Possibly. But this was boom-time China, when for even a passably competent musician – or a cobbled-together band exactly three practices old – becoming a rock god for an evening was as possible as anything else.

“A lot of the people attracted to China are attracted to things like art, literature and music,” says American Jonathan Heeter. “They have different conceptions of the way they want their world to work and are looking for a way to express that. Playing music, learning Chinese, these are different expressions of that same desire, to curate your own universe.”