- HBO true-crime documentary Traffickers profiles three drug dealers who ruled the narcotics trade in the lawless Golden Triangle in Thailand, Myanmar and Laos

“The Mekong massacre,” says journalist Jeff Howe, “was one of the largest killings of Chinese nationals outside China since World War II.”

And it was this slaying of 13 sailors aboard two cargo vessels on the morning of October 5, 2011, that reawakened the world to a notoriously criminal region, the Golden Triangle, and brought into public view Myanmar’s elusive freshwater pirate, Naw Kham.

Referred to as “a narco-state”, the area covers roughly 950,000 sq km (370,000 square miles) that incorporates the confluence of the Mekong and Ruak rivers and extends into Thailand, Myanmar and Laos. The territory remains the ultimate “traffickers’ paradise”. It has always been a hot spot for drug smuggling, and Howe is a key contributor to HBO Asia’s latest true-crime documentary series, Traffickers: Inside the Golden Triangle. His insights are aired along with those of former special agents, police commanders, aides to drug barons, fellow reporters and unlikely defenders of some savage public enemies since apprehended.

Today, the “deadly tentacles”, as the series puts it, reach further than ever, assuring the Golden Triangle remains “unquestionably the epicentre of illicit drug production”, enjoying additional benefits from a combination of pandemic and politics. Whatever hazy images its name might still evoke, this is no hippy dreamland as it was mythologised in the 1960s, but, according to Howe, “the craziest, most lawless, most scary-ass place you could ever travel to”.

Yet travel to it director Steve Chao and executive producer Dean Johnson did, at various times, with their crew, to tell the stories of three of the most heinous traffickers the region has known. Chao, also an investigative journalist, who has worked in assorted conflict zones, is only half-joking when he says, during a video call from the Malaysian capital Kuala Lumpur, “It’s comforting to know that your [executive producer] has a commando background and if you get into trouble he’ll be parachuting in to take down everybody and rescue you. It gives us confidence to know we can get in and out of places because of the training that Johno has.”

Although the expertise Johnson gained as a British Royal Marine was not called upon this time, he reveals that the team had “pretty good risk-security assessment and did operate in a militaristic kind of way when needed”.

Chao recalls, “The most dangerous moment was when we were trying to get access to those who had known the drug lords. Yes, these are drug lords past, but they still have influence and respect among the populace, because some are considered Robin Hoods who fought for Shan State independence or helped the locals.

Britain’s ‘shameful’ post-war expulsion of Chinese sailors

“We were trying to keep it quiet that we were on the Mekong River around Sam Puu Island, filming the biography of Naw Kham, and gunmen emerged from the jungle. We were open, exposed, stuck between the island and the mainland. They observed us for a tense minute or two, then gave us a nod and walked back into the jungle. We learned afterwards that there was probably a superlab nearby.”

Sam Puu Island had been the Myanmar base from which Naw Kham was able to extort protection money in the form of “taxes” from passing vessels; and it was in the vicinity that the 13 Chinese crew were murdered. Naw Kham and three subordinates were arrested by Lao police and handed over to the Chinese where they were paraded in front of news cameras before being executed by lethal injection in Kunming, Yunnan province, while nine other Thai associates were repatriated to face trial.

What caused Naw Kham and his gang to kill the Chinese crew is unclear. Had the crews refused to pay for illicit cargo, or a transit toll? Were drugs really aboard their boats? “That’s the bit of the mystery nobody can really answer,” says Johnson, dialling in from Bangkok, Thailand. “It’s not clear who ended up killing the sailors, although the court in Kunming was certain. It was a warning, but it was definitely over drugs.

“There’s no doubt cargo vessels are often forced to transport narcotics. I’ve made that river journey myself; for eight or nine hours you can’t see a single light, it is jungle and hills, so at certain stages boats are stopped and forced to carry other goods. The speculation was that there were drugs involved but there was no evidence of them [aboard the Chinese cargo vessels], it was just fruit.

“There’s a complex trafficking system: drugs come out of that area and will often cross to Laos, then come back into Thailand farther downriver [from the Myanmar side of the Mekong]. From there they go by vehicle across the Malaysian border in pickup trucks, then to Penang, then out aboard different vessels. The drugs are then transferred from smaller ships [to larger ones] and on to Australia and Japan. It’s better than Amazon – they have a better distribution system. It’s incredible.

“This is the great untold narcotics story. We’ve seen the Pablo Escobars and the Guzmáns. They’ve had so much media attention and Latin America stakes its claim as a sort of drugs kingdom. But in our own backyard the Golden Triangle is the big secret. It has a history of massive illicit drug production and trafficking and was once the world’s largest heroin exporter. And in Covid-19 times production has increased: year on year the numbers are growing. So even in a pandemic the traffickers have been able to use the region to their advantage – helped by the lack of a cohesive approach by law-enforcement agencies.”

Political upheaval has also played into the criminals’ hands. “The situation in Burma [Myanmar] has made things even worse,” says Johnson. “There had been attempts at law enforcement by Burmese drug agents in the greater Mekong subregion, and some had been trying to influence what was going on in Shan and Wa states. But since the February coup it has all been a complete no-go zone. The drugs are almost in free flow – more product than ever is coming out.”

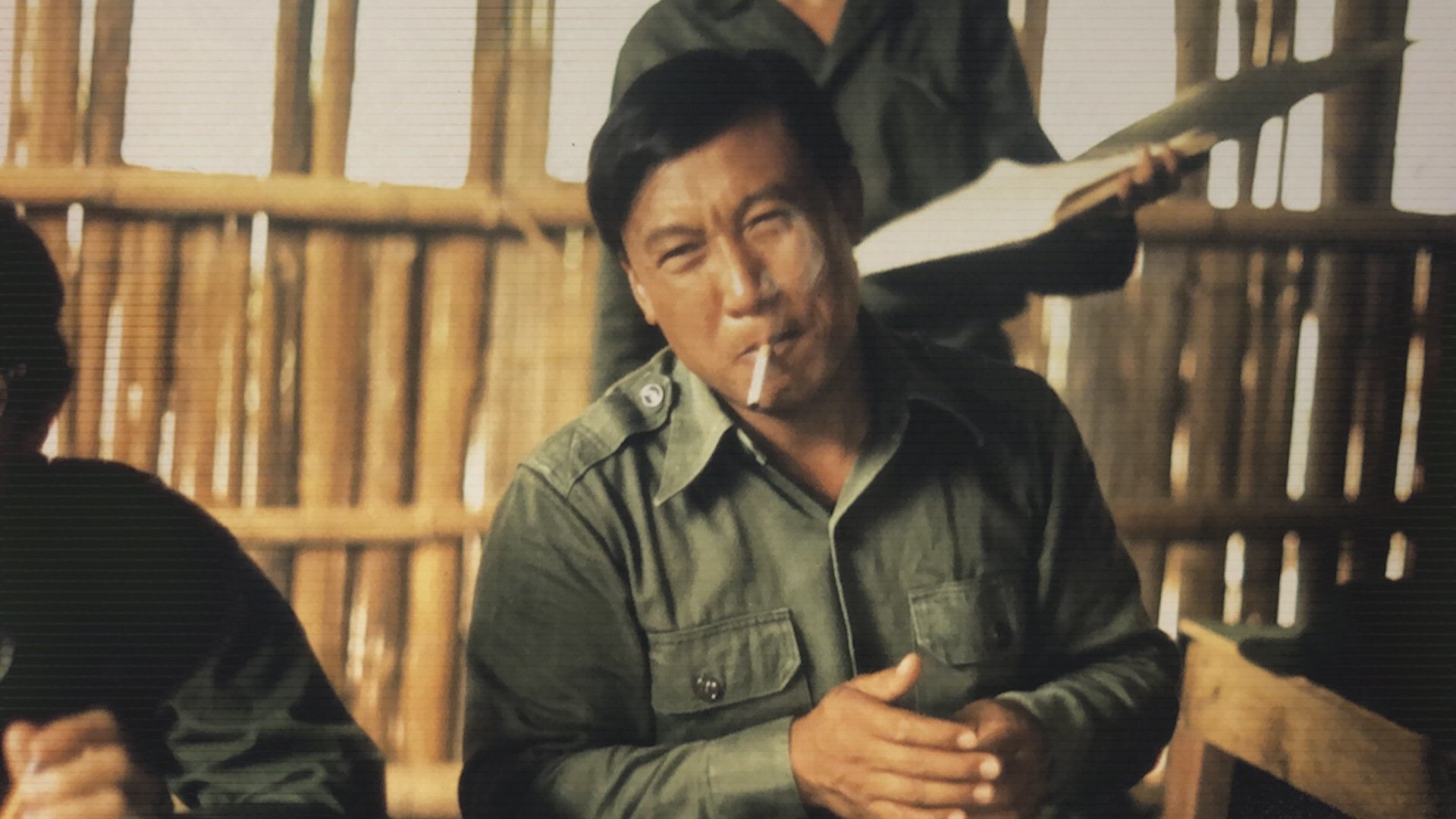

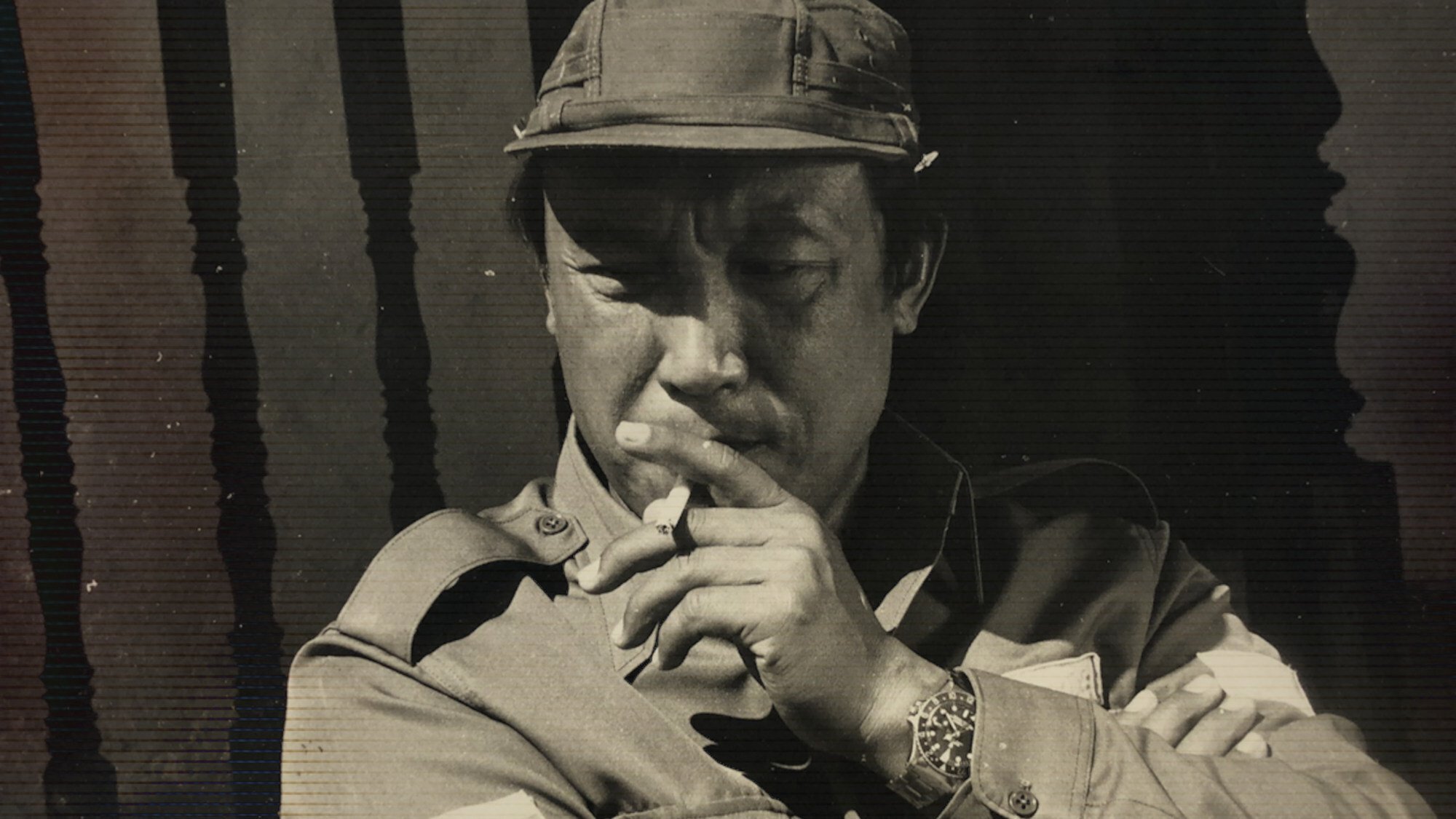

Though the drug barons and foot soldiers may have changed since the Golden Triangle’s first blush of notoriety, narcotics empires continue to operate with impunity and are still supported by the machinery of conflict. Illiterate warlord Khun Sa, the subject of part one of the documentary, was known as “the opium king” and styled himself the revolutionary leader of the 25,000-strong Shan United Army fighting for freedom for the ethnic Shan population. He was also known as “the prince of death”.

By the mid-1980s, Khun Sa was, according to Traffickers, making hundreds of millions of dollars a year from opium smuggling, far outstripping any profits accumulated by Pablo Escobar or Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzmán. Khun Sa ruled his kingdom from a military camp protected by anti-aircraft guns, among other defences, shown in extraordinary archive footage. And for some of today’s leading drug producers and smugglers, little has changed.

In the mountains, says Chao, “it’s still very much like that. When we were there filming, the Burmese government mounted a raid on a drugs laboratory and arrested numerous individuals. They were detaining them at their forward operating base when artillery began firing – artillery – from one of the militia groups, who were saying, ‘You’ve taken our men, that’s not on, we’re taking you out.’ And this was against the government.

“The Burmese were surrounded. At one point all the counter-drug people were on their knees in front of their compound, begging for their lives. They were about to be assassinated. Fortunately, the government was able to rally a military helicopter to fire on the militia and push them back to save the law-enforcement officers. But the entire compound was destroyed and the militia got their arrested men back. The Golden Triangle remains a lawless area controlled by militias with free rein to produce whatever drugs they want.”

Government raids or not, the stench of corruption lingers over the region’s black-market economy. “A mixture of autonomous groups is taking advantage of the situation and making money,” says Chao. “Where the military on the Burmese side comes in – from what we understand and from what other Burmese authorities tell us directly – is that they often turn a blind eye and make money that way. And they facilitate production by charging taxes to allow superlabs to operate. Despite attempts by the Burmese government to clean up, there’s a lot of complicity.”

Secrecy played an important part in the almost mythical status attained by the mysterious Khun Sa. (As Chao puts it: “Geography has a big part to play – we’re talking about a mountainous region with terrain that is so difficult to get into, where these groups have managed to carve out fiefdoms they can control. And that allows them to be bandits.”)

In 1988 Khun Sa, in a change of strategy, allowed himself to be tracked down and interviewed by Australian journalist Stephen Rice, and later filmed by British documentary maker Adrian Cowell.

To revisit the Golden Triangle of that era and present it to a new audience, Chao went, in Johnson’s words, “digging for gold in the United States”.

“Adrian Cowell [who died in 2011] is legendary among so many filmmakers,” says Chao. “It took a lot of phone calls to try to find his footage, but finally we heard he’d donated all of his canisters of film to the University of Washington, in Seattle. There were 2,000 rolls, in a basement, sitting on palettes in rusty canisters. So I spent a lot of time opening up and blowing the dust and rust off these canisters and in some cases going through the footage by hand.

“It was a gold mine. Cowell had made programmes on heroin and opium, but a lot of the footage had never been seen before. Luckily the archive had two spindles and I could look up at the film against the light. We chose the reels – and then the long, involved process of digitising the footage began.”

Tastes change – in illegal drugs just as in anything else – and some of today’s criminals eschew secrecy and modesty for the self-aggrandisement made possible by social media. Flaunting his wealth in innumerable posts led to the downfall of Laotian trafficker Xaysana Xkeopimpha, featured in the HBO documentary’s final instalment.

Arrested in 2017 in Thailand’s biggest drugs bust, Xkeopimpha was exposed as one of the major players behind the recent explosion in methamphetamine manufacture in the Golden Triangle, annually exporting trillions of meth and caffeine “crazy pills” known as yaba around the world. This shift in product, first seen during Naw Kham’s reign, has, says Chao, “made the region the world’s premium methamphetamine production centre”.

“This brings us back to the question of why we should focus on the Golden Triangle today,” says Johnson. “This place is special, because there is this unique opportunity to manufacture drugs without threat from law enforcement. Thirty years ago you needed 100 farmers to produce a kilogram of opium; now you can have three guys running a superlab and pumping out tonnes of methamphetamine every day. And whatever is new on the market is going to come out of here. These guys are supplying the globe.”

What might be the next illegal drug of choice? “The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime [UNODC] is watching that really carefully,” says Chao. “It’s probably going to be a synthetic, but exactly what is a big question. We’ve seen a resurgence in the manufacture of ketamine, which is popular in China, but experimentation goes on all the time among the syndicates. Criminal groups, [whether] operating under an authoritarian government or in a democracy, will always find ways to thrive.”

Beijing, says Chao, “has played a highly active role in trying to stop drug trafficking within and around China’s borders. But equally, the UNODC has been clear in saying that the majority of precursors – the chemicals that go into producing methamphetamine or ketamine – are coming from China. Then they are smuggled on barges across the Mekong into the Golden Triangle, where they become the drugs that are killing countless people around the world.”

As another expert Asia watcher declares on camera, there has “never been a better time to be a drug trafficker in the Golden Triangle”.

Traffickers: Inside the Golden Triangle will be available from July 23 on HBO Go.