Coronavirus: how India’s catastrophic failure in tackling its second wave doomed the country and cost an unimaginable – yet avoidable – toll on lives

- Misstepping at almost every turn, Prime Minister Narendra Modi set a number of examples for the world of what not to do

On April 21, Ashley Delaney took his father-in-law to the Goa Medical College and Hospital, the largest public hospital in the small southwestern Indian state. The facility was in chaos and the wards were packed, with all 708 Covid-19 beds occupied – so 69-year-old Joseph Paul Alvares, a cancer survivor, had to lie on a gurney for nearly three days until a bed became available.

The bathrooms were so filthy that many patients chose to wear adult nappies. And when one Covid-19-positive man began having seizures, the hospital staff – seemingly unable to cope – tethered him to the bedposts with bandages. Delaney was so disturbed by what he saw that he decided to stay by his father-in-law’s side in case things took a turn for the worse. Soon enough, they did.

On the morning of April 28, several patients’ monitors started to flash, indicating that they were in distress, but the hospital staff did not respond. When Delaney went to investigate, he found that the patients – about 10 to 12 of them, as he later recalled – had died. He was not a doctor, but it looked as if there had been a problem with the oxygen supplies.

Delaney alerted several nurses and doctors, who told him they had already complained to the administration but had been brushed aside. On May 2, the incident repeated itself. This time, 12 patients died. On the night of May 3, that number rose to 14.

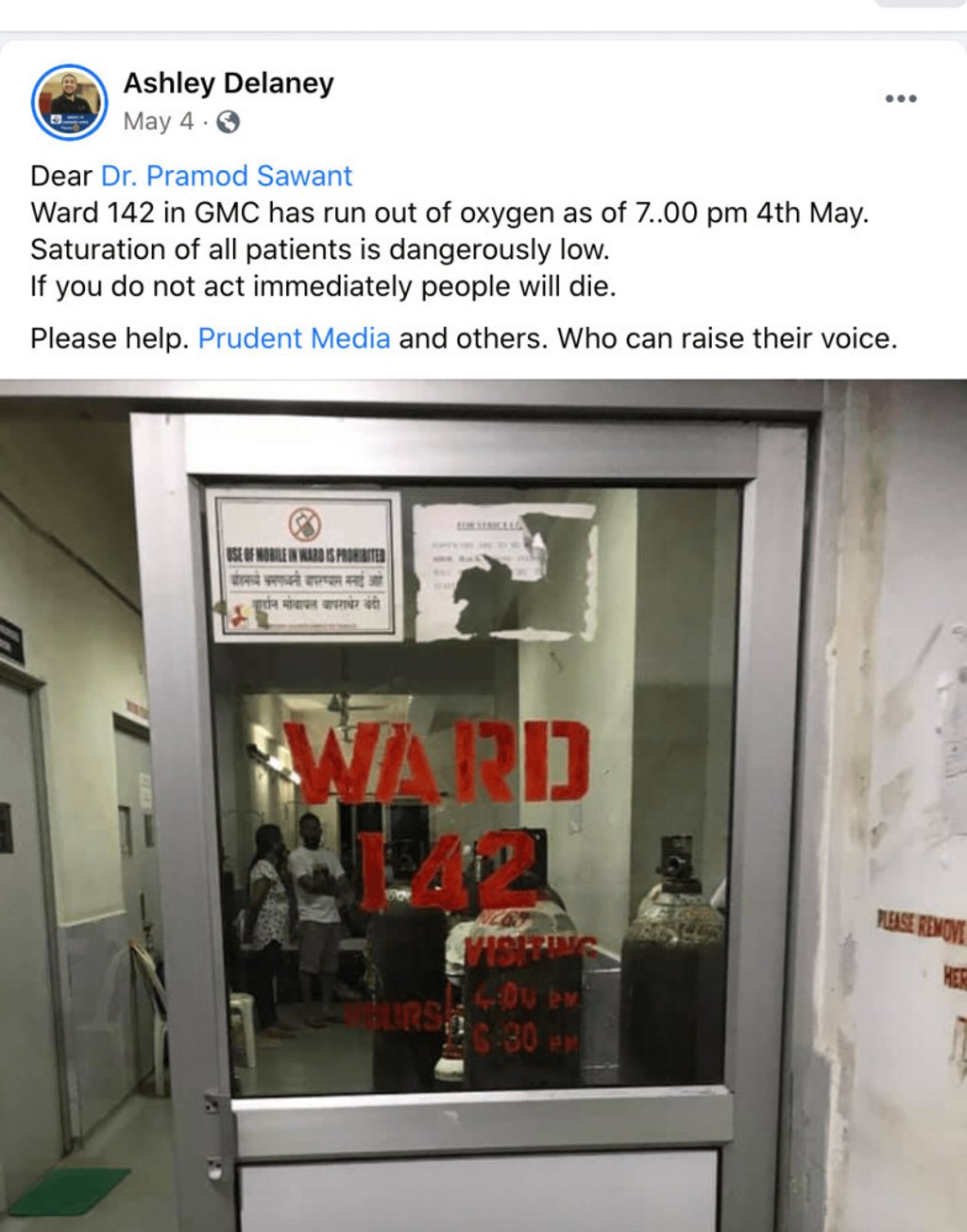

On May 4, after Delaney had been observing the Covid-19 wards for nearly two weeks, an entire ward ran out of oxygen. He saw a chance to save everyone affected – all the patients were still alive, though struggling – but when he approached staff, they confided they were afraid of reprisals from the hospital administration if they spoke up. After two patients died, he went public with his findings.