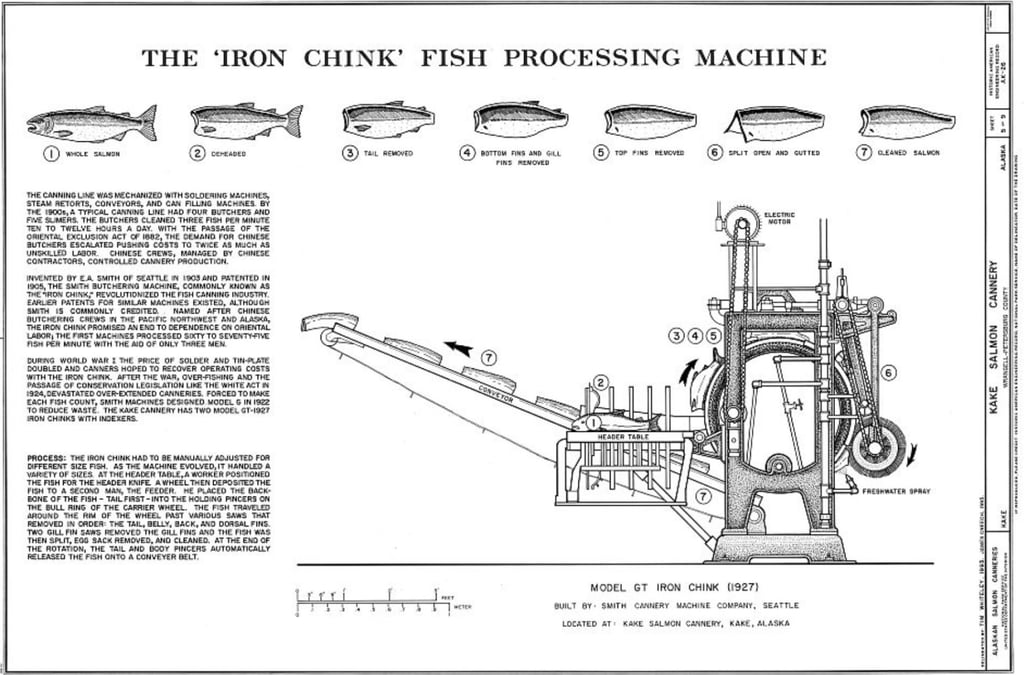

Chinese built the US salmon canning industry. ‘Iron Chink’ invention robbed them of their jobs – and insulted their ethnicity to boot

- The invention of a salmon-butchering machine put the final nail in the coffin of Chinese workers who had built up the US fish canning industry

James and Philip Chiao needed money for college, but few employers wanted to hire a couple of guys from Taiwan with no experience and funny accents. After weeks spent pounding the Seattle pavement, the twins spotted an advertisement for work at a salmon canning factory in Alaska.

That seemed a bit weird but also intriguing. They visited the local union hall daily and used their meagre savings for liquor to “soften up” the hiring boss until, on the last possible day, they landed jobs and headed to Alaska to spend months sloshing through guts, blood and fish scales.

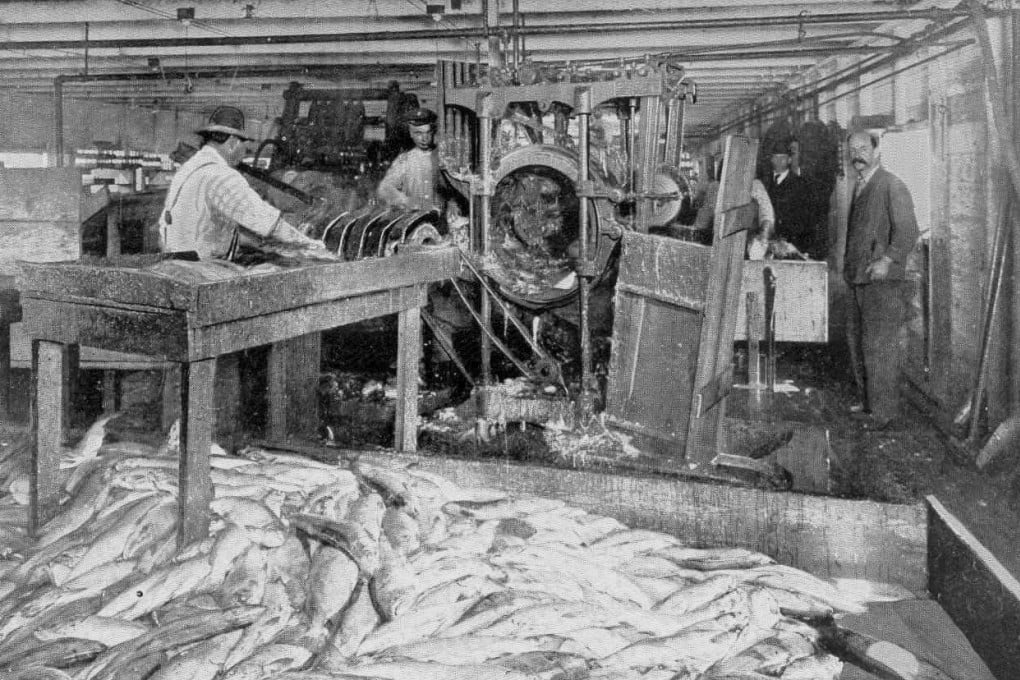

Other workers during that summer of 1970 were mostly Filipino and some Japanese. It would take them decades to realise that before them, the Chinese had dominated this once-vibrant industry for decades and that the clanking fish butchering machines were invented to do away with “upperty” Chinese workers.

The patented device’s racist name: the Iron Chink.

Now retired, the Chiaos are on a mission to educate people about the contribution of the Chinese to the salmon canning industry, and to highlight the prejudice that fuelled exploitation.