- What better time to celebrate nostalgia than Mid-Autumn Festival? We look back at some of Hong Kong’s turning points that shaped the city we know today

Hong Kong is ever-changing: skyscrapers and tower blocks mushroom on the city’s skyline, land is reclaimed along the harbourfront, new neighbourhoods redefine cool as transport networks spread their tentacles. And throughout the course of its history, social change in the city has been marked by a series of milestones that have shaped the way we live today.

Here, Post Magazine looks back at some famous Hong Kong firsts – from temples and social housing to nightspots and restaurants; turning points that in one way or another have signalled change in Hong Kong.

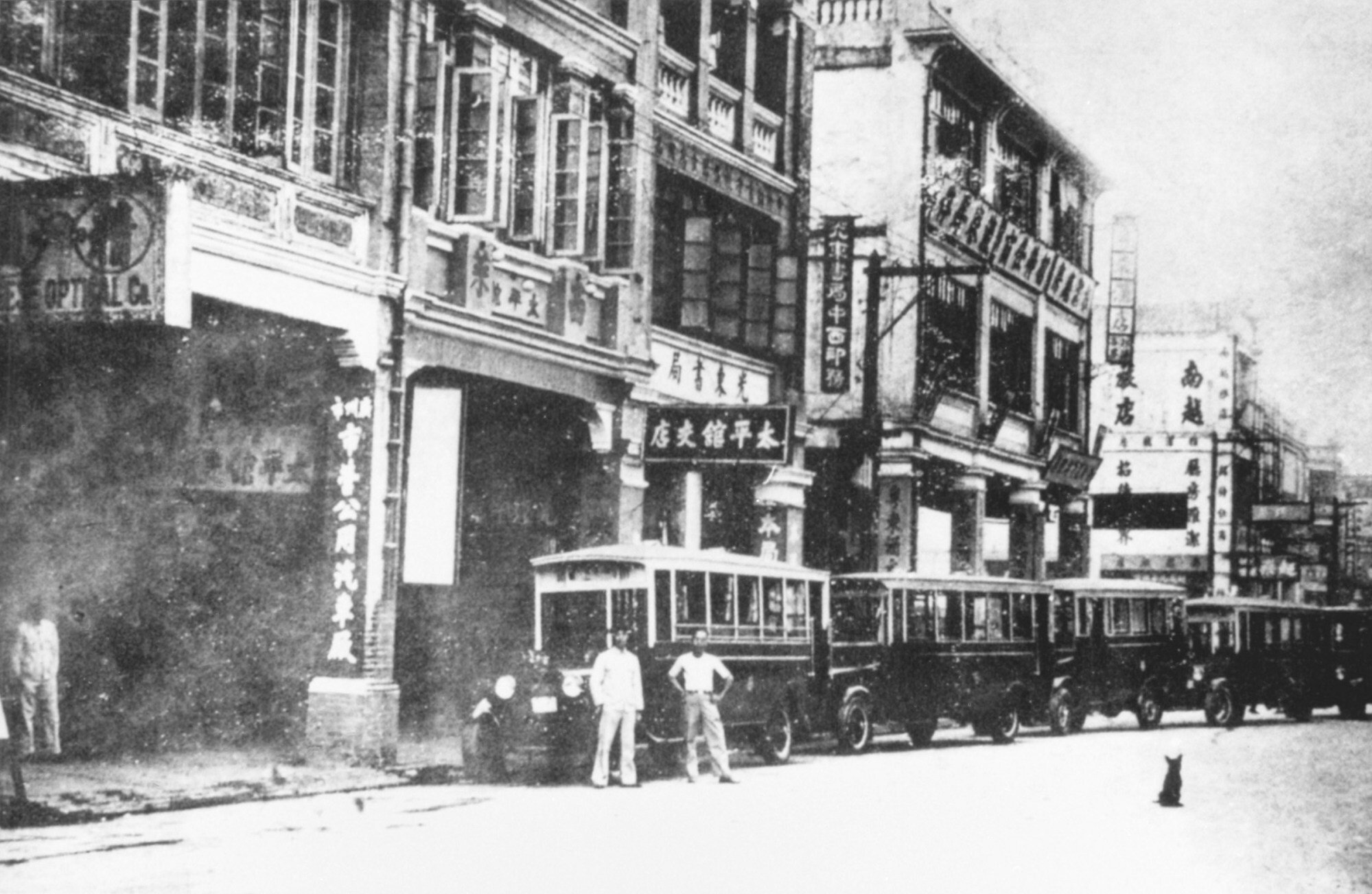

Tai Ping Koon: Hong Kong’s first fusion restaurant

Many of Hong Kong’s most beloved businesses are run by second-, third- or fourth-generation families, giving them their character and the sense of being intrinsic to the city’s fabric.

As Tai Ping Koon’s fifth-generation owner, Andrew Chui Shek-on beats them all. Softly spoken yet passionate about the fusion food his family helped to pioneer in the city, he says, “[Tai Ping Koon] is a Chinese restaurant legend.”

Inside the restaurant’s oldest branch, in Yau Ma Tei, orange tablecloths and leather booths channel 1960s glamour. And much like the decor, little has changed when it comes to the cuisine – Western dishes blended with Chinese ingredients to suit the tastes of locals.

Chui’s great-great-great-grandfather, Chui Lo Ko, opened his first restaurant in Guangzhou in 1860, where his dishes became known as “soy sauce Western”, due to his habit of adding soy sauce to everything in the belief that his Chinese guests would not want to stray too far outside their comfort zones.

Popular dishes included Swiss chicken wings marinated in a glaze of soy sauce, sugar, Shaoxing wine and spices – a stock that KFC would later adopt. Then there was the Portuguese-style, deep-fried pigeon that Sun Yat-sen would have delivered to his office, and a soy sauce steak so popular it made its way into the pages of The New York Times.

But by 1938, as the Sino-Japanese war intensified and soldiers approached the Canton restaurant, Chui Lo Ko moved his family and opened a new branch in Hong Kong. It was a decision that saved the business, the original being appropriated in 1956, when the Communist Party cracked down on private property. As the Cultural Revolution raged from 1966, the Guangzhou branch was renamed Eastern Wind and stripped of all Western influences.

Luckily, Tai Ping Koon found popularity in Hong Kong, where it would expand to four branches – Yau Ma Tei, Causeway Bay, Central and Tsim Sha Tsui – and Andrew Chui still visits each one daily. The hardest thing about being a legacy restaurant is having to maintain the quality of food from more than a century ago, he says. “We never hire chefs from other restaurants because even if you hire a five-star hotel chef, they still don’t know how to cook our food because it’s so special.”

Chui grew up spending happy weekends at those outlets but “when you take over the old family business there’s always a lot of challenges”, and, “I wasn’t sure I could handle it,” he says.

To be a success, “you have to love your business, not just consider it a job, but really give it passion”.

Tsing Shan Monastery: Buddhism’s birthplace in Hong Kong

Legend has it that in AD420, an Indian monk named Pui To crossed the sea from Guangdong to Hong Kong in a “wooden cup”. Upon arrival, he stopped to rest in a cave on Castle Peak. It was there that he began to share his Buddhist beliefs with a garrison of soldiers charged with guarding the checkpoint with China.

Unlike Taoism, the Buddhism Pui To preached emphasised karma and compassion, and today, the Tsing Shan Monastery, at the foot of Castle Peak, remains an impressive collection of eclectic structures that represent these ideals.

As it faces the wrecking ball, a eulogy to Hong Kong’s General Post Office

A red-brick Mahavira Hall greets visitors, decorated with a mural of the rotund Chinese monk Budai (also known as the Laughing Buddha). Two staircases lead up to the Precious Hall of the Great Hero, where three golden Buddha statues epitomise trikaya, the modes of being: the earthly state, the heavenly mode and the state of absolute knowledge.

“When Tsing Shan Monastery was established [in 1918], hundreds or up to 1,000 monks were ordained at a time, as many Southeast Asians would come to Tsing Shan following [the abbot] Chan Chun-ting,” says Wong Ming-fai, a religious consultant at the monastery. “But these days, only around 150 monks are ordained at a time and that number includes monks from all monasteries in Hong Kong and mainland China.”

The curved brick rooftops adorned with electric blue flowers, phoenixes and other mythical beasts are today little more than ornaments of the past, their symbolism relegated to the history books by an increasingly secular society.

“The decrease in numbers of monks might have to do with the improvement of living quality nowadays,” says Wong. “Many people in Hong Kong are becoming more wealthy, while the journey to becoming a monk can be tough. Also, the government does not have any policies to promote it, so it mainly relies on the efforts of monasteries.”

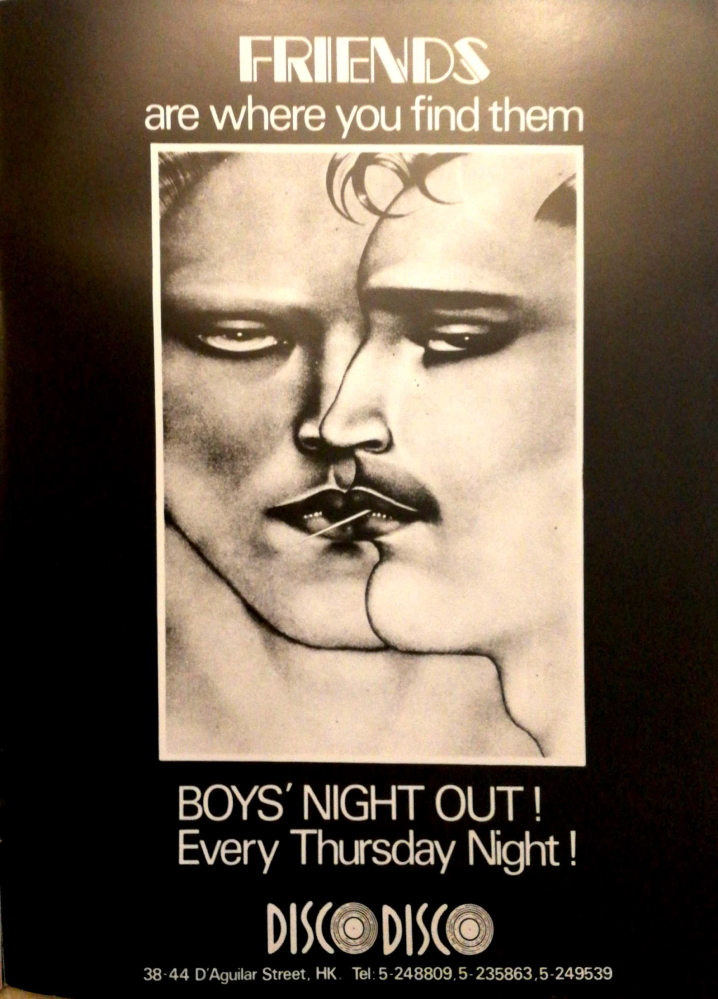

Disco Disco: The club that launched Lan Kwai Fong’s nightlife

In 1978, a year after Studio 54 opened its doors to the stylish, raucous exploits of New York’s artists, celebrities and socialites, Gordon Huthart transformed a tired basement on rat-infested D’Aguilar Street into a garish, Egyptian-inspired, queer-friendly nightclub called Disco Disco. The son of a prominent Lane Crawford director, he wanted a space to party in a city where homosexuality was still illegal.

In those days, there was not much of a party scene on Hong Kong Island, with most of the population living in Kowloon.

“It was very much a Kowloon-centric vibe,” says Andrew Bull, at the time a resident DJ at The Scene at The Peninsula, in Tsim Sha Tsui, and later Disco Disco, who went on to open his own club, Canton Disco, in the 1980s.

Before Huthart opened his club, Lan Kwai Fong was like any other residential area, with “bag ladies dragging flattened cardboard boxes up the street”, says Bull. “There was an Italian fashion shop and an Italian fast food place called X, which was damn excellent. The best meatball subs you’ll ever have.” But there was a reason for choosing that location – the MTR was due to begin operations.

Businessmen at Jardines and bankers at HSBC would swing by, leading to a mix of the gay, straight, expat and local.

“I think Hong Kong probably got the disco music before England,” says Bull. “England was 10 years behind in the 70s because they were trapped in a culture of ego DJs, who were famous for being personalities talking on the microphone. But disco, non-stop mixing, taking a crowd on journeys, came out of the gay clubs in New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles […] We were connected to New York and Paris, much more so than probably anything in London.”

Much like New York’s clubs, Disco Disco was instrumental in bringing about legal and social change when it came to LGBT rights. At the time, gay men were subject to police harassment – targeted by undercover officers at clubs and subject to cruel treatment. A year after the club opened, Huthart spent 13 weeks in prison for 15 counts of buggery.

“The disco era definitely pushed a lot of boundaries,” says Tedman Lee Pui-ming, producer of Cantonese-language documentary Night of the Living Discoheads (2012). “The 70s, 80s and 90s were actually quite open. But then in the 2000s, I don’t know what exactly happened, but it sort of got conservative again.”

“It’s like the stock market, it can go down as well as up,” says Bull. “Freedoms are hard-earned and have to be underpinned but they can be undermined, as we’re seeing in many other aspects of life. Just because you’ve got freedom, it doesn’t mean it lasts forever. It’s like chewing gum, you have to keep getting a new one.”

Shek Kip Mei: The estate that transformed Hong Kong public housing

On Christmas Day 1953, a fire ravaged the scrap-metal homes of the Shek Kip Mei squatter area, leaving more than 53,000 people homeless overnight. Like most of the settlement’s residents, Szeto Kwok-ling and his family had immigrated from China, escaping the civil war that raged there in the late 1940s.

In an interview with Post 41 magazine, he recalls that night clearly: his father had gone out to watch Chinese opera while he stayed at home with his mother and younger sister. After the terror of running from their burning home, he joined thousands of residents wandering the streets of Sham Shui Po in search of temporary shelter, ultimately settling on a staircase outside a church on Cheung Sha Wan Road.

Because the disaster affected so many, the Hong Kong government was forced to intervene and build resettlement blocks to house victims of the fire.

Szeto remembers the joy of the day the blocks were completed, a few years later, and he was able to live in a bricks-and-mortar home for the first time.

Designed in an H shape, the Shek Kip Mei Estate became a thriving community – mimicked across the city from the 50s to the 70s, housing a low-income labour force that spurred Hong Kong’s economic boom. Those who had owned shops in the squatter area were offered 240 sq ft stores in the estate while entrepreneurial residents started new businesses wherever they could.

In 1963 and 1964, hawker Au Yeung-to worked under the staircase of Block H. Known as the “wonton-noodle kid”, he would wake at 4pm and ride his bicycle to Sham Shui Po’s Pei Ho Street Market, where he bought fresh produce before making his broth and wrapping his wontons, which he served from 8pm until 1am.

But while Shek Kip Mei might have been welcomed by the community in the 50s, as immigrants fled wars across Asia, today’s residents are disillusioned by the lack of services in the new estates. In one of the most expensive and densely populated cities in the world, where most Hongkongers are unable to afford homes, there are calls for the government to find a long-term solution to the needs of the working class.

7-Eleven: Happy Valley store the first of a thousand

Convenience store 7-Eleven has been open every day of the pandemic – just as it was during the protests of 2019 and typhoons such as Mangkhut, which battered Hong Kong in 2018. And throughout its 40-year history in the city, Cheng Wai-ching has worked six days a week at the store. She has witnessed the franchise grow from a single shop on Wong Nai Chung Road, in Happy Valley, to more than 1,000 branches.

Today, she works with her daughter, Jowei, in the area’s Sing Woo Road branch, bringing the charm of a family-owned shop to the American retailer, which operates more than 60,000 convenience stores worldwide.

“Back in the day, there were old convenience stores and everyone in the neighbourhood would know each other,” says Jowei. “They know you and they know your family. We would like our store to be like that. We know each other and their next generation. We remember their needs. When they visit the store, they don’t need to say anything – we know what they want.”

Cheng, 68, has become friends with her regular customers. “I have witnessed a customer’s daughter go through different stages of life: before she started dating; when she got married – the customer gave us bridal cakes; and when her son was born she visited us,” she says. “Now, her mother and I sometimes meet and have dim sum together. Even during the pandemic, when we were not able to see each other, we would call to update each other.”

Customers also tell Cheng if they are going to emigrate or move from the neighbourhood, so she does not worry about them.

The global chain was founded as Southland Ice Company in 1927, with a Dallas-based store selling blocks of ice for food preservation to households without refrigerators. A year later, a woman named Jenna Lira placed a totem pole she had bought as a souvenir in Alaska in front of the store, a gimmick that attracted so much attention the name was changed to Tote’m Stores, before a rebranding as 7-Eleven in 1946, to reflect the company’s new extended opening hours.

But it wasn’t all smooth sailing. After the stock market crash of the 1980s, chairman and CEO John Philp Thompson, son of founder Joe C. Thompson, sold large chunks of the company to Ito-Yokado, ultimately transferring 70 per cent of control to the Japanese affiliate. It is perhaps no surprise, then, that Asia has become dominated by 7-Eleven stores. There are more than 20,000 stores in Japan, 10,000 in both Thailand and South Korea, and, after Macau, Hong Kong boasts the second-highest density of 7-Eleven stores in the world.

Cheng has worked at “tsat jai” or “little seven”, as it has been colloquially known, since 1981, when 7-Eleven first opened in the city. “I’ve never thought about doing other jobs after I joined the business,” she says. “I also didn’t know it had been over 40 years since I started working in 7-Eleven. Time flies.”

Ocean Terminal: The city’s first shopping mall, in Tsim Sha Tsui

Back in the 1960s, few public spaces had air conditioning, which is why the city’s first American-style shopping mall, Ocean Terminal, came as a relief for many Hongkongers.

“[Shopping malls] are, in effect, parks,” says Gordon Mathews, co-author of the 2001 book Consuming Hong Kong, with Lui Tai-lok. “In Hong Kong, at least for four, five, six months a year, you wouldn’t want to go to a park. That’s why air conditioning, and shopping centres in particular, were of considerable importance.”

Unlike the United States, Canada and Britain, where the growth of shopping centres coincided with rising affluence and car ownership, in Hong Kong, such malls did not spring from suburbanisation but rather from a service sector that targeted tourists from overseas.

When Ocean Terminal opened, on March 22, 1966, the 2,000 tourists on board the P&O cruise ship Canberra were the shopping mall’s first customers, and they were welcomed with fireworks and a lion dance. But it was young Hongkongers that would ultimately reap the benefits of the mall and its 112 shops.

“The subsequent localisation of the shopping mall culture was an outcome of growing affluence among the local people and the development of a local consumption culture since the 1970s,” writes Lui.

Chinese built up salmon canning in US. Then came the ‘Iron Chink’

Manufacturing was booming – the number of factories had risen from 3,000 in the 50s to 10,000 a decade later, with the textile industry supporting about a quarter of Hong Kong’s population. And as GDP, which was still low in 1960, began to rise, standards of living, including education and health care, increased dramatically and people were able to consume beyond what they needed to survive.

But consumption in Hong Kong differed greatly from that in the West. Even the wealthy rarely had the space to hoard, so it took on a different pattern, with a premium placed on buying new items but not holding onto them for long. Otherwise, consumers focused their spending on eating and drinking out.

That said, malls are rarely more than a space in which to window shop and hang out with friends while tasting the lifestyles of affluent foreigners.

“For the locals, the unfamiliarity of such architectural and socio-economic settings of high consumption was itself an attraction,” writes Lui. “It served the function of delineating the boundary between the mundane reality of the locals’ everyday life on the one hand, and the fantasy of alternative ways of life on the other.”