- Author Victoria Finlay traces the fascinating origins of China’s silk industry in this edited excerpt from her latest book

“They can’t fly,” says the manager of the Brochier Soieries silk shop in the old quarter of Lyons, France. “Their bodies are too fat. Or their wings are too big. Or something. Anyway, they’d never get off the ground.”

I’ve never seen a silk moth before. And now here are two, on a table outside this shop. When I was a child, I learned that if it flies by day it’s a butterfly and if it flies by night it’s a moth. But what if it doesn’t fly at all?

The manager, Eliza Ploia, smiles. “There are some other differences between a butterfly and a moth,” she says, and I search on my phone for a list: moths have ears and butterflies can’t hear.

Butterflies are usually coloured, and moths are usually more plain. Butterflies eat and drink and moths don’t even have mouths. When moths are resting they usually keep their wings open; butterflies usually have them closed. And finally, and this is of course critical for silk, moth caterpillars generally spin cocoons, and butterfly caterpillars generally don’t.

I look at the moths on the table. They’re balancing on wooden rods sticking up from what looks like a cribbage board. Their wings are huge and fluffy, like white rabbit ears or toy donkey ears, and their antennae are like oversized eyelashes fringed with dark threads. Their eyes are black buttons, and their plump bodies are covered with soft hair. Below is a broken cocoon from which one of them has emerged. It’s the size of a robin’s egg and yellow as a lemon. All around is a delicate mesh of fibre catching the sunlight.

“Can I touch?” I ask. It feels soft. When I close my eyes I’m not even sure my fingers are making contact with anything. I think of how the fineness of a silk filament was once the mark against which all textiles were measured.

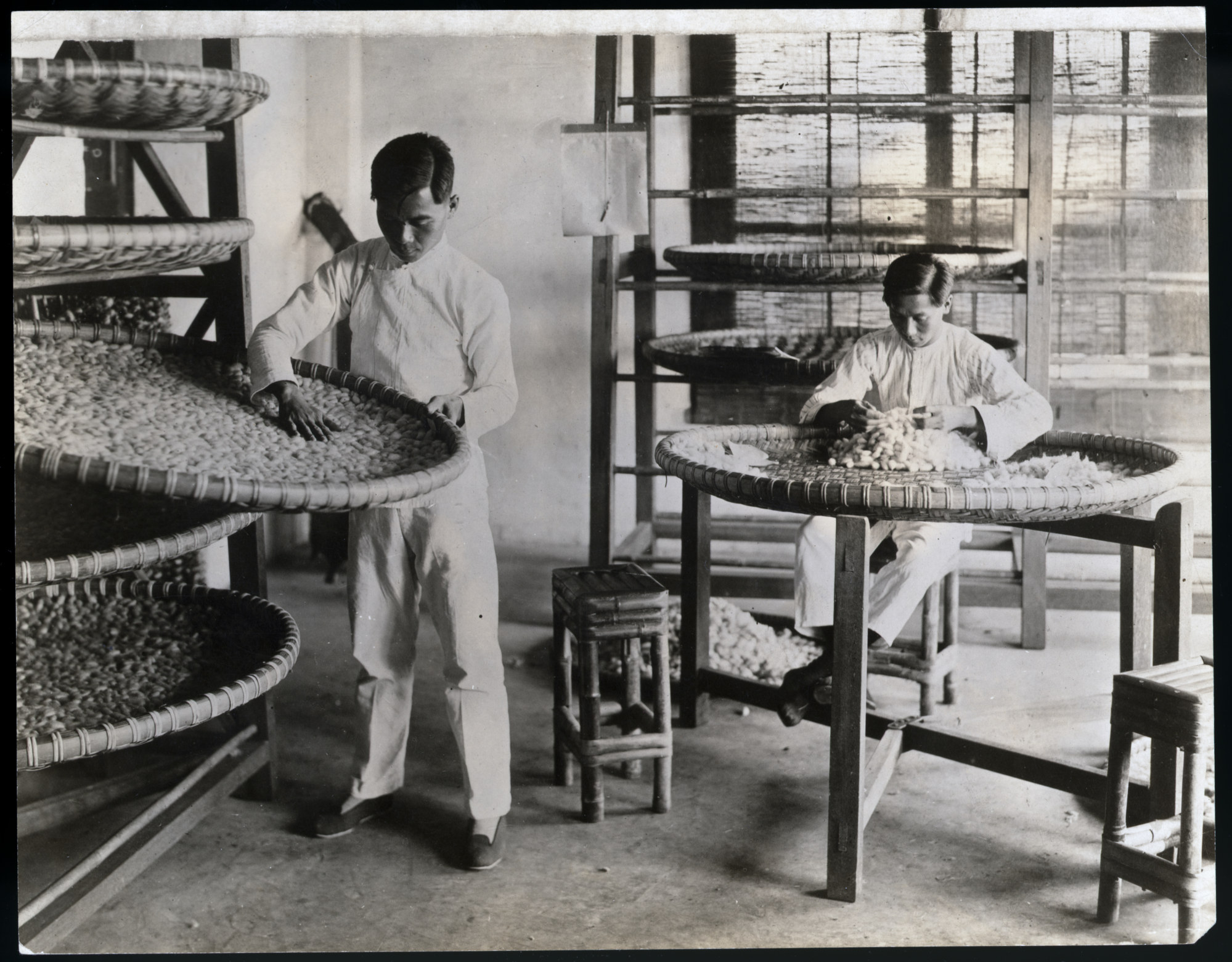

The two moths have recently mated, Eliza says. They’ll stay together for a few days then the male will die first, the female not long after. Later, she lets me sit in a room at the back of the shop where there are hundreds of caterpillars, divided in trays by age. The little ones are a week old. When they hatch from eggs the size of sesame seeds, they look like brown ants.

Now they’re the size and shape of white mulberries, which is hardly a coincidence as just about the only food they can consume without getting sick is the leaves of the white mulberry tree, Morus alba. The leaves, which were picked three days ago, are already curling. They smell vaguely of green tea; some people drink them as an infusion to reduce diabetes and heart disease.

“The worms shed their skin four times and then they are ready,” Eliza says. On the last table, there’s another of the boards with rods sticking up. The biggest worms, or “fifth instars”, are climbing them, reaching out like dancers, weaving their fate. With the light behind them, I can see through their bodies: a long dark alimentary canal, a heart beating.

What China’s Evergrande crisis means for its property market and the world

Becoming translucent is one of the signs that they are preparing to build a cocoon, starting with the outer reaches, sketching out the general shape with generous sweeps, then, as the cocoon gets close to being finished, the worm needs less movement to get to the inside edges. So it weaves tighter and tighter in smaller and smaller movements until in the end it hardly needs to move at all to keep painting its continuous pattern on the wall of its own cave.

The secretions come out of two glands in its head, each containing a liquid protein called fibroin and a liquid gum called sericin, which react with each other to make a single, solid thread. A line of cocoons has been laid out on the table. The larvae inside are dead. When I pick one up, it rattles as if there’s a dried bean inside. The casing is very light. It takes five or six thousand to make a kilogram (2.2 pounds) of thread.

This one is about the size of a quail’s egg, though it’s more elongated, like a peanut in its shell. It smells of oxtail soup. In a row, they look like a colour chart for 1950s kitchen equipment. Cream white. Citron yellow. Yolk orange. Dusky pink. Chestnut brown. The colours are from natural pigments in the sericin, the gum that surrounds the cocoon to resist the rain and which tastes bitter to deter predators.

The difference comes from how the individual worms process carotenoids and other substances in the leaves: it’s genetic, like how some people have blue eyes and others have brown.

And anyway, when the cocoons are later softened in hot water to dissolve the gum, most of the thread turns out white.

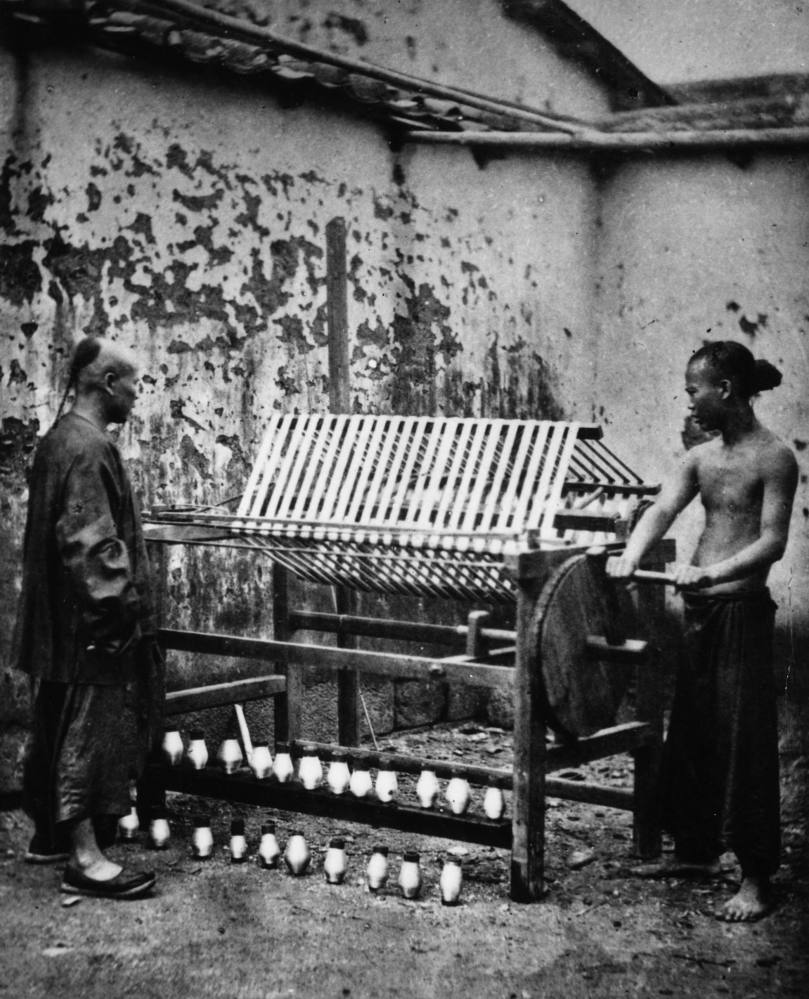

I knew that in old China the cocoons would be placed in a basin of hot water and stirred with bamboo sticks until the end of the thread could be located and the whole kilometre (0.6 miles) or so – together with the silk of four or five other cocoons needed to make something strong enough to be a usable thread – could be reeled out with a precise amount of tension using a simple turning wheel. And I knew that trillions of pupae died in the cocoon every year to make silk, and that this had happened every year for thousands of years.

Behind the trays I notice the silt-coloured saucepan where most of these animals will die. I move it away. I know they can’t see it, but it doesn’t seem kind. The oldest ones in the final tray have run out of food. I take a handful of leaves from a pile in the corner and put them in the tray.

The silkworms glide towards them, pushing into and over each other as they compete for the leaves. I see how they have crescents and stars and what look like eyes on the backs of their thoraxes and abdomens. And their noses, moving and exploring, look like the heads of seahorses.

Which, given the most popular origin story of silk in China, makes perfect sense. It begins with a girl who lives in the mountains, far away from anywhere. Her father receives a summons to fight for the king and leaves. After a year the girl begins to wonder where he is, and after another year, she starts to worry. One day she’s tending to her horse and whispering her fears about her father, when the horse begins to speak, promising, “I’ll go and find your father.”

“Could you?” asks the girl.

“I can. And I ask just one thing in return.”

“What’s that?”

“I’d want to marry you.”

The girl looks the horse up and down. And she sees that it is strong and rather nice-looking, and she knows that it has always been a good horse. So she agrees.

The horse gallops over mountains and plains, to far-flung rivers and probably to far-flung constellations (this is a very ancient legend after all) and eventually finds the father and brings him home. At first, the father is grateful. But then he learns what his daughter has promised, and he’s furious. He kills the horse, chops off its head, skins it and then leaves the hide to dry.

In one version, the girl runs away in distress. In a darker version, she’s complicit, and kicks the hide to punish the horse for its lustful thoughts. Either way, she runs away, chased by the decapitated head of the horse, which, when it catches her, covers her head, while the horse’s skin wraps itself around her body. The father looks for her everywhere. And just as he is about to give up, he finds her on a mulberry tree. She has become a silkworm with a horse’s head, and she’s weaving herself the cocoon from which she will emerge as a goddess.

The horse-headed Mother, or the Silkworm Woman, Can Nü, is still worshipped today in some parts of China. On her festival day, silk farmers in rural China still buy paper cut-outs of her, placing them in their workshops to ask her to give them an excellent harvest.

“Don’t worry,” said his minister. “It’s not hard to make silk. You just need three things. Mulberry trees, silkworms and people who know how to cultivate them.”

The advice didn’t strike the king as helpful. The Chinese emperor had issued an edict forbidding anyone to export mulberry trees or silkworms or silk experts.

“But what if you married a Chinese princess?” the minister suggested.

The king agreed.

The minister went to the Han emperor’s court to make the arrangements, and when he had the chance to talk with the chosen princess in private, he explained the situation. At first she didn’t want to disobey her father, the emperor. And anyway, how could she get silkworms through the Yumenguan pass when the guards were searching absolutely everyone?

When they reached the pass that marked the border of China, everyone was searched. When they were done, the princess was allowed to continue, but her entire entourage, except her personal maids, were told to go back. The minister was convinced he had failed. But when they were a long way from the pass, the princess removed her headdress and picked tiny silkworm eggs out of her hair. And the mulberry? She opened her medicine cabinet, and there were dozens of seeds.

“Some of them are mulberry,” she said. “It’s so hard to tell the difference.”

“Ah,” said the minister. “But we don’t have the silk experts.”

“We actually do.” The princess called her maids over. “It’s the women not the men who look after silkworms,” she said.

And that, according to one legend, is how the skill of mulberry silk cultivation passed out of China and to the regions of Central Asia and Persia – where craftspeople began to excel in the making of luxury brocades – and then moved further west. It’s not that there wasn’t other silk elsewhere. There are dozens of species of wild moths all around the warmer climates of the world whose cocoons can be unwound to make into yarn.

The most celebrated in ancient Greece was Coa vestis – “Kos cloth” – named after the island where there were wild silk moths living on turpentine trees. The philosopher Aristotle in the fourth century BC said it had been invented on Kos many centuries before and that there was a class of women on the island who would unreel the cocoons and then weave a fabric “with the threads thus unwound”.

But this came from a different kind of moth – and the silk was not as fine as that from the Chinese Bombyx mori. The West African equivalent was the Anaphe moth, which lives on the tamarind tree. Unlike most other silk moths, its caterpillars are communal, and a colony of several hundred will spin themselves into one large cocoon. The cocoon is beige, although inside – where each individual pupa is enclosed in its own pocket – the silk is white. It’s woven into a cloth called aso oke, and worn only during ceremonies, and especially funerals.

Anaphe were never domesticated, although in northern Nigeria people would encourage them by growing tamarind. When a hunter found a cocoon, he’d take it to market, and if it still contained any pupae he’d get more for it, because after the silk had been removed, the insects could be roasted and eaten. The cocoon nests would generally be used as purses, or, later, as bags for storing gunpowder while hunting.

In Madagascar there’s another wild silkworm, Borocera madagascariensis, which is made into a cloth called lamba landy. It is expensive but it is also dangerous, as its threads are full of tiny hairs that can penetrate the skin and cause infections. It means that you have to trust the maker. It also means that it can take up to a month to make a single metre of cloth.

In the past it was for the royal family, and even today it’s only worn on special occasions, or occasionally used to wrap the dead, when families can afford such an expensive shroud. People used to say that the cocoons of the Borocera moths have “no limbs but many feet”, because they were so precious they were worth trading over long distances.

Although the secrets of growing silk remained guarded, mulberry silk from China has been travelling west for at least 3,000 years. Threads from a silk bonnet or ribbon have been found wound into the hair of a woman who died in Thebes in Egypt around 1000BC. We know it was most likely from China because the Chinese had a particular way of degumming the fibres by boiling them in soapy water to make them softer and better able to absorb dyes.

The Ancient Greeks called China “Seres” which is like calling it “Silkland” using the old Chinese word for silk, si.

That is how, according to legend, the making of weft-faced brocade first came to China: as a knock-off copy of a knock-off copy

Around the fifth century BC, there was a burst of international trade in silk leaving China. It went north to Siberia, where it has been found in graves in the Pazyryk Valley of the Altai Mountains. It also travelled west towards Europe along Persia’s “Royal Road”. The journey was always dangerous, and by the beginning of the Han dynasty, in the second century BC, it had become life-threatening.

Even the Great Wall, built after around 500BC, couldn’t stop them for long, although its construction could be a reason for the surge in silk exports around that time, because it made it safer for trade caravans to travel. In the interests of forging an alliance, in 138BC Emperor Wu sent an emissary to Fergana, in today’s Uzbekistan. Despite being captured by the Xiongnu, Zhang Qian finally reached his destination and returned to the Chinese emperor with knowledge not only about the nomads but also about lands as far away as Syria.

In Fergana itself he was most amazed to see how many Chinese trade goods there already were in every town. He’d thought he was going to exotic places far from anything he knew; instead he found many things that were familiar, including fabric woven in Chengdu, thousands of miles away. With Zhang’s hard-won information, the emperor was able to establish four military outpost towns (all in today’s Gansu province) as well as a network of post offices and manned watchtowers to protect the trade routes from bandits and war gangs.

He also increased tribute to the Xiongnu, who loved Chinese silk. In part they craved it because growing mulberries and cultivating silkworms requires land and peaceful lifestyles, so they couldn’t produce it even if they knew how. And in part they needed it because, as well as being luxurious and lovely, it was extremely useful worn in battle, under your armour. It could stop some arrows penetrating, and if they did get through without killing you, it made them easier to pull out.

This was the era when silk really started to move. One of its destinations was imperial Rome, already a place of emperors and excess, where both men and women were only too happy to buy as much silk as could be transported to them across the passes of Central Asia. Around AD70, Pliny the Elder complained in his Natural History that the fashion for silk clothing among Roman nobles was causing a drain on bullion.

Imitations go both ways. From the top of the watchtowers built by Emperor Wu, the guards would have seen many caravans winding along the tracks below them. Many traders carried jin, a rich brocade invented around the eighth century BC. Jin thread is made by winding gold around a core of silk, and the patterns made from it were so elaborate that when the cloth first appeared in the markets of Baghdad and beyond nobody could work out how it was done.

Here’s the thing: a woven cloth can be warp-faced or weft-faced or a balance of the two. In the former, the warp threads are so close together that you can’t see the wefts except at the selvedges. A weft-faced cloth is the opposite, and you can usually tell if a handwoven cloth is weft-faced because motifs can be repeated more easily across the width of the fabric (because they’re all created at the same time) and not so easily along the warp (where the timing might be separated by days or even months, and where the tension or even the dye-batch might by then be slightly different).

The Han weavers specialised in warp-faced jin brocade. But when the Persians (of today’s Iran) and the Sogdians (of today’s Uzbekistan and Tajikistan) tried to copy it, they made their version weft-faced because it was the only way they knew. The exercise involved reinventing their own carpet looms, or zilu, using a system of multiple suspended heddles connecting the ordinary warp threads with the extra patterning threads.

It was a triumph of technical adaptation and it meant that they also applied some of the Chinese jin effects to their own traditional fabric and carpet designs, achieving another kind of transformation. And so the two systems coexisted. Then, hundreds of years later, in the early seventh century, an emperor of China in the Sui dynasty received a stunning Persian brocade as a gift.

“How do they do it?” he asked his palace weavers.

He told them to copy it and that is how, according to legend, the making of weft-faced brocade first came to China: as a knock-off copy of a knock-off copy, made valuable because it was favoured by an emperor.

At China’s National Silk Museum, in Hangzhou, the first object I see is a clay jar, about 30cm high, with a neck as wide as a dinner plate and a pleasing, plumped-out shape tapering to a slim base. It had been broken into fragments the size of a child’s hands, but now the pieces have been mended with conserving cement of a paler colour, so you can see the joins. The jar is dark grey and has a gritty texture.

One day, or one night, more than 5,000 years ago, a mother, or a father or a priest or even a stranger, bent or knelt or stood in front of this jar and placed the body of an infant inside it. It was a tiny child, older than a newborn, younger than a toddler. She or he was wrapped tightly in two kinds of silk: one a tabby and the other a pink gauze. The tabby is the earliest woven silk ever found, probably made with a backstrap loom. And the gauze is among the earliest coloured textiles of any kind. Experts at the Shanghai Textile Research Institute think it was dyed using iron ore.

The jar was buried in a tomb at Qingtai village in Henan province. It was found in 1984 by a team from the Zhengzhou Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology who were excavating three other tombs in the area when they came across this one. This jar was in pieces but it was clear that it had been the last resting place of a Neolithic child whose community did not know much about metal but did know how to reel silk.

They also knew how to weave it into cloth. And they knew how to wrap it to keep a dead child warm. The two silks from the Neolithic burial aren’t on display at the National Silk Museum. They’re too fragile and need to be kept in the dark. But nearby there are several silks from Qianshanyang, near Huzhou, beside the lower Yangtze River, which are 4,400 years old.

He used to install spy cameras in China, now he roots them out

The cache was found in a tomb in 1958 and it included fragments of blackened silk tabby as well as silk ribbons and silk thread, all found in a flattened bamboo basket, like somebody’s needlework case, ready for the next world.

Silk is good in graves. It lasts longer than most other natural fabrics. I remember reading an account from Philadelphia in 1824, of how the coffin of the daughter of the former governor, William Denny, was dug up to enable the installation of iron pipes in a road beside the burial ground. Her body, which had been interred some 30 years earlier, disintegrated as soon as it met the air but the “silk riband” on her dress was almost untouched. It was so well preserved that the gravedigger’s daughter kept it and wore it afterwards.

The truth is, worms and insects don’t much like silk. Moth larvae rarely make holes in it when they find it in wardrobes. They don’t like to eat their own.

Fabric: The Hidden History of the Material World (Profile Books) will be published in November.