How US scheme to catch Chinese spies in American corporations and labs is enabling what it tries to prevent, amid accusations of racial profiling and calls to shut parts down

- Launched in 2018, the China Initiative has largely failed to root out espionage, but has succeeded in driving many pioneering scientists back to China

Inside a Kansas City courtroom, Peter Zeidenberg is growing frustrated. The wiry, grey-haired American lawyer isn’t making much headway persuading a judge to throw out evidence obtained as a result of what he calls misconduct by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

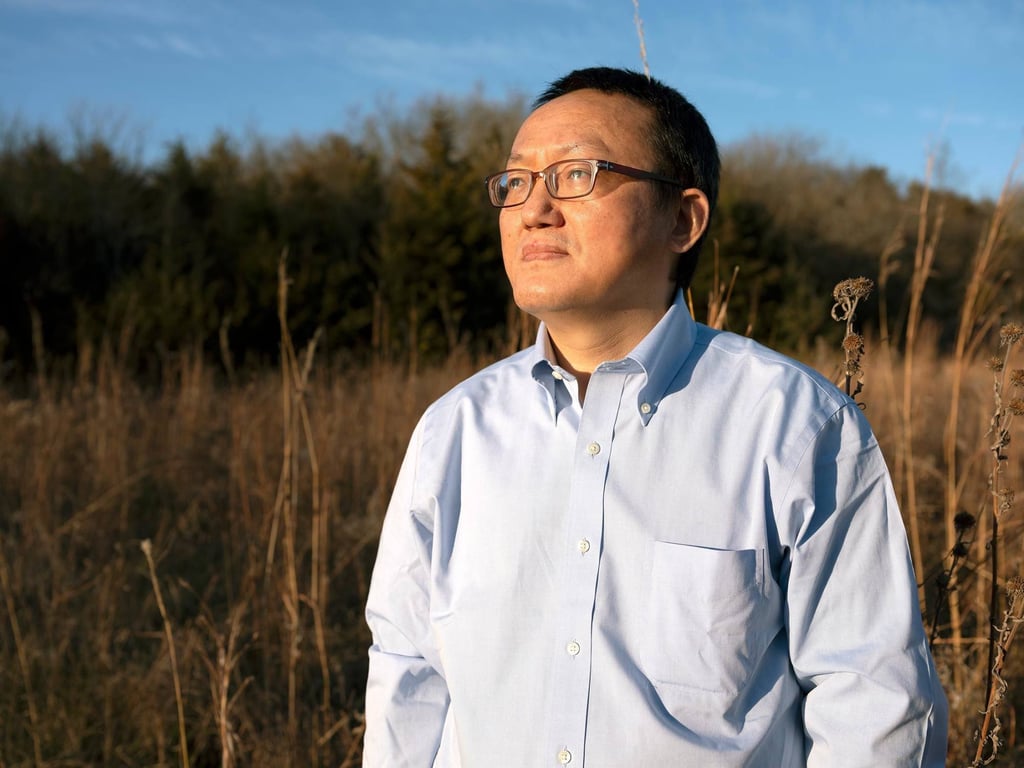

His client, Franklin Tao, a former University of Kansas chemical engineering professor facing 20 years in prison, is furiously scribbling notes and passing them to his defence team.

“They were looking for a spy, looking for evidence of espionage of trade secrets,” Zeidenberg says, his voice rising in exasperation. But they found none, he says, because there wasn’t any. “At the end of the day, they just have a conflict-of-interest form where the box wasn’t checked.”

Tao is accused of failing to disclose ties to a Chinese university while employed in Kansas. His prosecution is part of the China Initiative, a sweeping effort by the Department of Justice, the FBI and other federal agencies launched in November 2018.

One primary goal was to counter Chinese espionage in America’s corporations and research labs by rooting out spies and halting the transfer of information and technology to China.

The FBI says it has opened thousands of investigations involving China since then. But recent setbacks – six cases dropped last July and a directed acquittal in September – have revealed law enforcement errors and prosecutorial overzealousness.