- They call each other ‘fam’, cheer those doing well and commiserate with those who get ‘rekt’ – they belong to online communities driving cryptocurrencies

I can’t explain exactly how I ended up on crypto Twitter (or CT, as it is known in the cryptosphere) and in the cryptocurrency-focused Telegram and Discord groups I started lurking in late last summer.

There was a bull run (when stock prices are on the rise) going on at the time – market confidence was high, investors were buying and prices were going up – and whenever cryptocurrency values skyrocket, the press spew headlines about improbable fortunes.

The subject was impossible to avoid, and my long-standing if until now private, nerdy interest in the machinery of our enigmatic financial markets propelled me towards it.

At first I felt a little dirty, a little shameful. Everyone is in these spaces for one reason: to make money. It’s a subject that remains uncouth to speak about in my wider professional and social milieu.

Soon, though, my shame started to interest me. I stayed a little longer, thumbing through channels on the train or in bed late at night. It’s a kind of rubbernecking only the internet allows, providing access to a subculture to which you don’t belong.

The new world of NFTs and crypto art, where digital works sell for millions

I learned to distinguish the swing traders and scalpers from the hodlers (hold on for dear life) and degens (degenerates, or speculation addicts) by the way they talk and post.

Across the forums, I could not discern any unified politics other than a shared certainty that the government and wealthy elites are keeping the little guy down.

Reporting on financial markets tends towards extremes. There is the mystifying description of market movements, in which Byzantine concepts are compressed into small units of abstract language, and then there are the individual stories.

In reports on the cryptocurrency markets, these stories generally feature people during a bull run getting rich through dumb luck or getting rich and then losing it all.

These are not, for the most part, wealthy people intent on obtaining more wealth. They are people trying to teach themselves how to get ahead in ways they believe were once closed to them.

They call one another “fam”, cheering on those who make a winning trade and commiserating with those who get “rekt”, as if they aren’t all opponents on the trading battleground.

The more time I spent in the cryptosphere, the more I came to see it as a place where all our economic ills are refracted.

I’m not here to whine I have accepted how life is and I am patient. I’m going to try so hard to grow my US$83.Social media post by a small cryptocurrency investor

When I started thinking about cryptocurrency, I came to the discourse with a set of preconceptions about what I would find. The lofty vision of a transparent and fair financial system had mostly given way to the public worship of the appetites.

Talk about crypto’s “radical potential”, whatever the politics, had been replaced by a caricature of Silicon Valley hype men and gym rats who pose in front of luxury sports cars and post their Rolexes. (A good day in cryptocurrency can equal a year’s worth of returns on the stock market.)

Most of what I’d gleaned about this part of the cryptosphere I had absorbed from the internet or the news.

I came to understand that cryptocurrency is a term not precise enough to describe the projects under its umbrella. It’s more than bitcoin and ether and the occasional meme coin: it’s thousands of projects with corresponding tokens, most of them unrelated to the ambition of replacing the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency.

Five-star hotel accepts bitcoin and ethereum to woo ‘clients of the future’

Admins serve as the bridge between the project team and the community and share updates. For some projects, support can resemble something like religious faith, insofar as the devotion seems incommensurate with the project’s outputs.

Imagine an Amazon-run Telegram channel where stockholders gather to make friends, cheer the launch of a new service, or squawk at company reps when they aren’t responsive enough. You can’t. It would never happen. But it happens here, in cryptocurrency.

I looked around these online spaces and found that every token, every project, was at the mercy of the hype cycle, or what people in the cryptosphere call “narratives”.

Apart from trading, the main strategy people rely on to make money is to identify the newest hype, get in early, and then pivot to the next, ahead of the herd. If you study the charts, you can watch the money move from one speculative focus to the next.

A few of them are people with genuine skill and knowledge, or “OGs” who traded through at least one of the previous bull runs and, over time, built followings through displays of wisdom about how to grow a portfolio and trade the charts. Some even produce free educational content and preach the gospel of risk management (for example, never risk more than one per cent of your portfolio).

But no small number appear to be marketers paid to push a token on their followers. They buy the token at low prices – or are given some as payment – then promote the token once the price is inflated. When their followers buy the token, it gives them the opportunity to exit their position at these higher prices (every seller needs a buyer).

But the charlatans tend to give themselves away by posting a lot of “hopium” (“#bitcoin rewards those who are patient”, “I hope all 950,000+ of my Twitter followers become #crypto millionaires in 2022!”).

China’s selfie king Meitu bets on bitcoin and ether

There are outright scams, too, among all the legitimate projects. It’s the norm for developers to remain anonymous, and anyone can easily spin up a token and corresponding liquidity pool to make it available on a decentralised exchange.

Tweet anything containing the words MetaMask or Trust Wallet, the names of two widely used crypto wallets, and phishing bots unfailingly turn up posing as support staff. After luring the unsuspecting into their DMs and convincing them to give up their seed phrase (a kind of password), scammers immediately use it to drain the wallet of funds.

All this I expected to find. What I did not expect to find in this corner of the cryptosphere was an overwhelming number of seemingly ordinary people of all ages – some still teenagers, others parents of small children or carers to older family members – desperate to make money to get by.

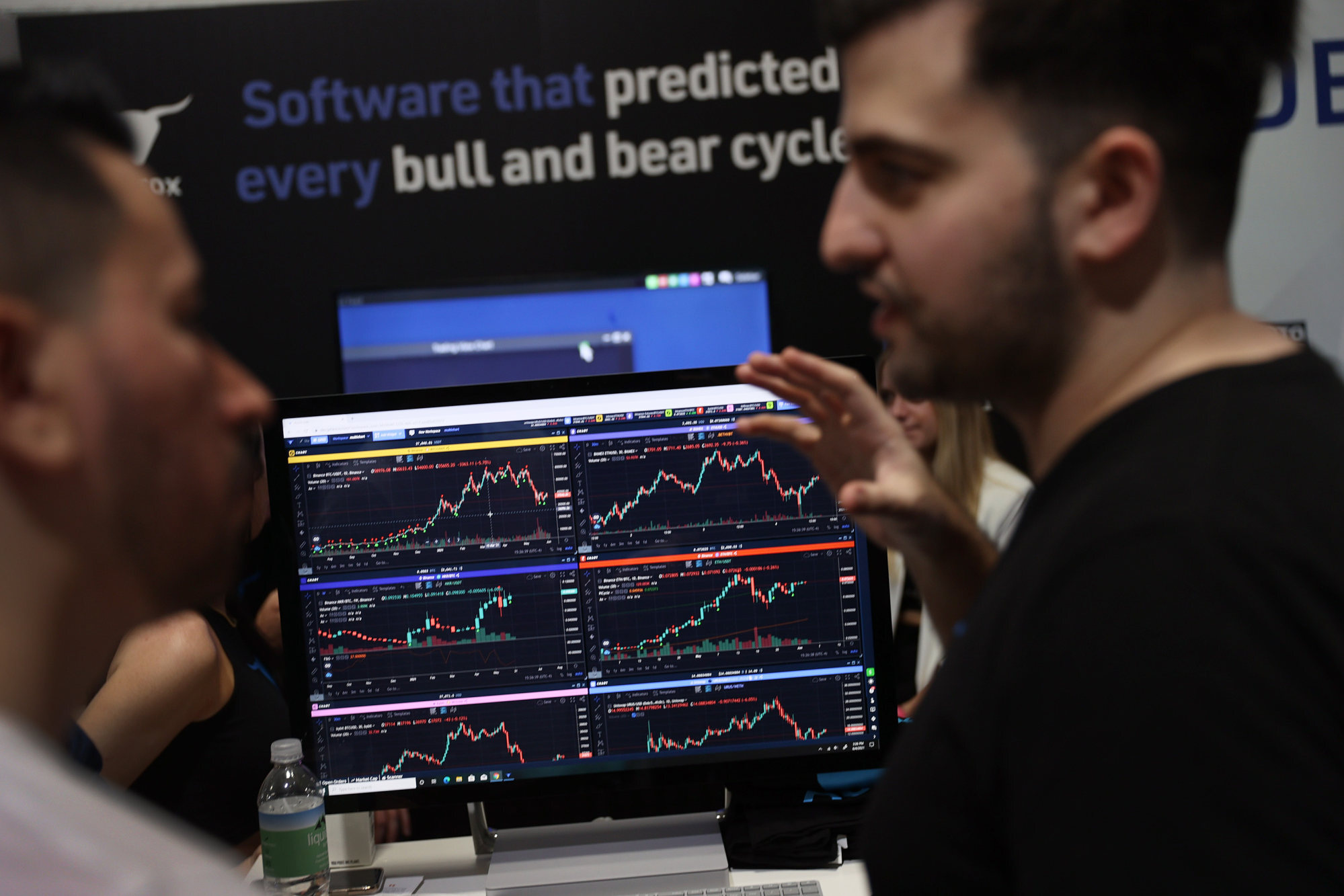

These were not the people I imagined seated behind a multi-screen trading set-up or moving assets around an investment portfolio. Many were here, trying to make money in cryptocurrency, because they felt they had no other choice. People struggling financially, who despise their jobs, who feel the system is rigged and there is no way out.

People whose country has been at war for years and want to leave, or who have left and want to help family members who stayed behind. From cryptocurrency, they draw optimism for the future, the possibility that their lives could change, or that they could change the lives of others:

“I have only US$100 to put in. My wife stays home with our baby and I work full time and do delivery apps on weekends to make extra.”

“Don’t assume that if things are going well for you they are going well for everyone. I’m a girl in uni and take care of my whole family. I’m not here to whine I have accepted how life is and I am patient. I’m going to try so hard to grow my US$83. This group on its own motivates me a lot.”

“I had constant stress about my investments but today all of it went away. Saw three people die, two of them were my close friends and [I] made it out safely after [I] got shot at four times. I was busy trying to make money, never would have thought things could go this wrong. Appreciate life and spend time with family and friends.”

Even the best financial advisers here promote [in-game tokens] … and people are crazy about it coz they’re really earning.A post from a Discord user in the Philippines

“I’m 17. If I stay here in my country after uni and work I can earn maybe US$100 a week max.”

“Can’t wait to tell my manager to eat s*** and walk away like a boss.”

“I came to Kabul a few days ago and what [I] saw here made me devastated, kids starving and their parents begging for a single piece of bread. I tried to help as much as possible, bought rice bags, oils, flour, clothes, blankets to many families, but [I] cannot do this alone.

“I wanted to create a gofundme [a fundraising site] link but its not possible here since [I] am in [Afghanistan]. I urge you guys to pray for everyone here and if possible, help them financially. You don’t have to be a Muslim to feel the pain of [A]fghans, you just need to be a human.”

“Got a dollar raise at work today lol, they felt like it was so nice of them but it’s really not s***.”

“If I’m starting with US$10, is that enough?”

Cryptocurrency crash wipes out more than US$1 trillion in value

These expressions of frustration and, at times, despair, are from people living in the United States, Britain, India, Turkey and Afghanistan. The countless other messages I’ve seen like these span an even wider geography. They surface amid the casual misogyny, the dick talk, the advice on managing steroid-induced anxiety – men (and occasionally women) letting their guard down in moments of vulnerability.

This is especially true in places where local currencies are weak. In the Philippines especially, but also in Venezuela and Brazil, people played a Pokémon Go-style game called Axie Infinity because it was more lucrative than other forms of employment. You play the game, you earn digital assets, and you cash out these assets for local currency. The value in local currency fluctuates, of course.

“Here in the [Philippines],” someone wrote on a Discord forum in early August, “lockdowns are so frequent so people are striving and trying to take chances in ‘play to earn’ stuff. Even the best financial advisers here promote [in-game tokens] $AXS, $SLP and $Skill now and people are crazy about it coz they’re really earning.”

In places where unemployment levels are already recovering from pandemic highs, disgruntlement about wages, working conditions and work-life balance may be intensifying.

We maybe consider that there might be an alternative to living our lives in thrall to the wealthiest among us, serving their profitBenjamin Hunnicutt, historian, in comments to the Financial Times

More than 4.5 million Americans resigned from their jobs in November 2021, up from 4.2 million in October, a phenomenon known as the Great Resignation. Some version of this is also taking place in Australia, Germany, Britain and elsewhere.

It’s likely more of a reshuffling than a resignation proper, as workers leave their jobs for better ones, or to work for themselves. Still, in the US, labour participation rates remain below pre-pandemic levels and haven’t budged. At least 4 million people have not yet returned to the labour force.

It’s not hard to imagine why: for such a wealthy country, the US treats many of its workers cruelly, with low wages, long hours and rampant instability. Even those with better jobs, materially speaking, may find themselves unfulfilled as they “spend their entire working lives performing tasks they secretly believe do not really need to be performed”, as the late American anthropologist David Graeber wrote in an article that was the basis of his 2018 book, Bulls***Jobs.

Speaking on behalf of the subreddit, historian Benjamin Hunnicutt told the Financial Times, “We maybe consider that there might be an alternative to living our lives in thrall to the wealthiest among us, serving their profit.”

The hypermasculine tenor of most day-trading groups, where technical analysis is the primary profit-making strategy, suggests that most cryptocurrency traders are male.

The spirit of the DeFi groups is a little different from the day traders’ toxic jock vibe. It’s less macho – maybe because these spaces have rules about conduct and moderators who enforce them. It’s here that every financial product you might access through a bank is being replicated. That users can remain anonymous, supporters say, removes the barriers that leave so many people unbanked or unable to access credit.

Still, I was surprised to learn that, according to NORC, a research institute at the University of Chicago, 41 per cent of cryptocurrency traders in the US are women. I also assumed that most investors would be younger than me, in their early to mid-20s, but the average investor is 38 – an age that, being not far off my own, I can’t help but reflect on.

It’s the age at which I began to find it increasingly difficult to suppress anxiety around my own financial vulnerabilities. From this vantage, the appeal of being able to fill in gaps or respond to a financial emergency by transforming US$100 into US$1,000 in the span of hours or days, not years, is more legible to me. If you’re desperate, the time horizon for other kinds of change – at the policy level, say – can seem too far off.

When you have been locked out of the system, when you haven’t had pathways to create generational wealth, you see this as an opportunityCleve Mesidor, founder of the National Policy Network of Women of Colour in Blockchain

But even in the US, the numbers appear to paint a different portrait. NORC’s study also found that 44 per cent of crypto investors are people of colour (compared with 35 per cent of stockholders), and 55 per cent do not have a college degree. In the US, people of colour on average earn less than white people, are more likely to have crushing debt, and are less likely to own their homes.

Only a small fraction of the US$130 trillion of wealth in America belongs to them. This aligns with the sentiments I’ve seen expressed on the forums: that people are there because they feel the odds of getting a leg up are stacked against them.

When I dug a little deeper, I found some reporting on these stats with a human angle. Last December, The Washington Post ran a story about Penelope and America Lopez, twins who saved their immigrant parents from financial ruin because of investments they made in cryptocurrency.

The article quotes Cleve Mesidor, the founder of the National Policy Network of Women of Colour in Blockchain (and a former Obama appointee who worked in the commerce department), explaining crypto’s allure: “When you have been locked out of the system, when you haven’t had pathways to create generational wealth, you see this as an opportunity.”

Artists, cryptocurrency firms use NFTs for philanthropic causes

For Time magazine, reporter Janell Ross went to the Black Blockchain Summit at Howard University in Washington in September 2021 and described the roughly 1,500 “Black crypto traders, educators, marketers and market makers” there as a “world that seemingly mushroomed during the pandemic, rallying around the idea that this is the boon that Black America needs”. There are risks, these authors observe, but whether they outweigh the potential rewards remains an open debate.

The risks are worth considering. Is replacing an exploitative, exclusionary system with an inherently vulnerable, unpredictable one a remedy to this system, or merely a reflection of just how debased it’s become? There are no stats on how many lose money in cryptocurrency, but there are many hazards not be obvious to inexperienced investors.

There are the risks related to security and the lack of consumer protections, to volatility often linked to price manipulation by so-called whales: exchanges, investors, market makers and individuals who hold tokens in such large quantities that they can move the price on their own. (Unlike in traditional finance, there is no regulating entity watching the market for manipulation strategies.)

There are the risks related to liquidation cascades, in which large institutional selling (or buying) induces a deluge of forced selling (or buying), the result of which is no small number of individuals with emptied accounts. Exchange platforms tend to suffer outages, making it impossible to log on and take action to protect your money.

They nuked wages so bad that now [people] have to gamble their way up the food chain through marketsTweet by a crypto influencer

In the broader context, equal opportunity to participate looks like an equal opportunity to get wiped out.

I keep returning to the idea that our present is a kind of reverse mirror image of the one in which bitcoin was launched. We are living in the aftermath of an economic crisis and, in the US, the Federal Reserve is in the spotlight. But conditions are markedly different: growth is high (not low), unemployment is low (not high), and wages are rising at the fastest rate in 20 years.

These are signs that the US economy has muscle. But its vigour is being overshadowed by inflation. In the past 12 months, the price of buying a home in the US has soared by nearly 20 per cent – an increase that, according to one estimate, will force working-class households approaching home ownership before the pandemic to resume saving for another five to 10 years.

The price of meat, poultry, fish and eggs has gone up by around 12.5 per cent; the price of fruit and vegetables by about 5 per cent; and the price of electricity by 6.3 per cent. It’s hard not to feel defeat. All the news of rising wages notwithstanding, the average earner is actually worse off than they were a year ago.

When there’s inflation, it’s the Fed’s mandate to rein it in. The cryptosphere has been following the Fed’s activities with the kind of dedication I would expect for football, not central banking. In the days preceding a meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee, or an appearance of Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell before the press, the acronym FOMC (Federal Open Market Committee) circulates through Discord and CT with the frequency of a filler word.

I notice how attuned people outside the US are to dollar imperialism. As Powell began to signal that the Fed would end its quantitative easing programme and raise interest rates, the US equities market reacted by selling riskier assets. The more speculative sectors of the market, such as tech stocks, took a tumble. Many in the cryptosphere appeared surprised when the cryptocurrency market began to sell off, too.

There is a contradiction that those who truly believe that crypto exists outside our financial system will have to contend with: this latest bull run appears to have been fuelled by government stimulus and by easy monetary policy, and the removal of these policies, at least at the time of writing, seems to have brought it to an end.

A recent survey of 100 hedge fund officers found that by 2026, executives expect their portfolios to hold an average of 7.2 per cent of their assets in cryptocurrency; in the US the average is even higher, at 10.6 per cent. Meanwhile, venture capitalists have been pouring money into the sector: an astonishing US$32.8 billion in 2021.

The moneyed art world – the commercial galleries, the auction houses – are already profiting from NFTs. And this year’s Super Bowl, the championship game of the National Football League, was dubbed the Crypto Bowl on account of all the cryptocurrency-related ads to which viewers were subjected.

Why NFTs and cryptocurrency appeal to K-pop labels

If cryptocurrency is a complex Ponzi scheme (a type of investment fraud), it’s one that mainstream institutions are clamouring to get in on. The fear of missing out is too overwhelming. The same institutions, the same wealthy elite, the same forces that early cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin and ethereum were supposedly protesting, could now subsume their antagonists, rendering them impotent.

As with the co-opting of any subculture, it can no longer be called a protest against the “system” if it is the system. There’s nothing inherent in the technology that makes it resistant to being assimilated by the ruling financial order.

There’s also nothing inherent in the technology that guarantees the multimillionaires and billionaires minted by cryptocurrency will be more benevolent elites than the ones we have now.

In December, a crypto influencer tweeted a sentence I haven’t been able to shake: “They nuked wages so bad that now [people] have to gamble their way up the food chain through markets.”

It’s a devastating description for being true and unvarnished, though I’m anxious that the worst is still to come. If the Fed starts to raise interest rates, making it more expensive to borrow money, it will discourage investment by employers and decelerate the economy, which could even slump into a recession.

BTS agency Hybe in NFT venture with cryptocurrency giant Dunamu

Either way, the unemployment rate is destined to go up, which means that working people will have less leverage to bargain for higher wages, which means they will have less purchasing power and, eventually, prices will stabilise to reflect this. It’s a strategy that forces workers to pick up the tab. But so far, higher wages do not appear to be amplifying inflation.

A study published by the US non-profit organisation Economic Policy Institute in January reveals that in sectors where inflation is high, it is generally not because wages are high. Meanwhile, CEOs are bragging to their shareholders about marked-up prices and unparalleled profits, and using inflation as a cover. From American multinational conglomerate corporation 3M’s most recent earnings call: “The team has done a marvellous job in driving price. Price has gone up from 0.1 per cent to 1.4 per cent to 2.6 per cent.”

All the while, the casino beckons. But we already know how that ends. We already know that the house always wins.

This report first appeared in n+1