- In an excerpt from a forthcoming book, Patrick Chiu writes that Watsons started in China, supplied opiates under licence, and today has stores all over Asia

The origins of Hong Kong’s ubiquitous pharmacy Watsons date back to 1828, to a clinic in the Pearl River Delta.

In the port city of Canton (Guangzhou), a simple clinic was established by Dr James H. Braford to provide free eye surgery for locals. It expanded to become the Canton Dispensary in 1832 – the first retail chemist and druggist to install a soda fountain in China – and later that decade, Alexander Anderson and Peter Young, both naval surgeons in the British military as well as the East India Company, volunteered there.

When England declared Hong Kong’s occupation on January 26, 1841, Anderson and Young followed the empire south, and jointly set up an apothecary at Possession Point, on Hong Kong Island, then opened the Hong Kong Dispensary at Morgan’s Bazaar in Admiralty, on January 1, 1843.

They were among a handful of chemists who supplied Western medicine and consumer goods to the merchant navy and sailors passing through the then city of Victoria. Two years later, the foundation stone of the Dispensary was laid at 16 Queen’s Road, where the New World Tower now stands.

That same year, upon graduation from the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Edinburgh, Thomas Boswell Watson journeyed to the Far East, acquiring Dr Anderson’s other clinic in Macau, with his wife, Elizabeth, joining him the following year. In 1848, T.B. Watson wrote to his sister in Scotland about life in Macau, remarking that in addition to the Portuguese, “we count ourselves only four families and one or two Americans and French”.

In 1856, after 12 years in Macau, T.B. Watson sold his clinical practice and joined the Dispensary in Hong Kong as senior partner. His health deteriorated the following year, so he invited his brother’s third son, Alexander Skirving Watson, then aged 22, to come to Hong Kong to take over.

Upon his arrival, A S Watson increased the supply of medicine to the merchant navy, sailors and the expatriate community. Within a year, he had successfully transformed the Dispensary from a medical clinic into a fully fledged retail chemist.

In those days, almost all Hong Kong laws were local adaptations of English laws, to ensure the same governance system was in place in the colonies. Peculiar among them was the licensing of opium. A S Watson was one of a handful of chemists authorised to dispense and supply opium to those with medical needs.

The 1858 legislation was titled “An Ordinance for Licensing and Regulating the Sale of Prepared Opium”, which allowed for preparing and selling of the drug “for medicinal purposes by a medical practitioner, chemist or druggist having a European or American diploma”.

A S Watson became the leading chemist supplying laudanum (opium mixed with alcohol) and other narcotics to transiting freighters seeking pain relief in the 1850s. The Dispensary soon became the largest wholesaler by manufacturing the Watsons brand of laudanum as a household medicine. Watson went back to England in 1865 but his return home would not last long. He died in Brompton, Middlesex, on November 29, 1865.

After Alexander Skirving’s early demise, a man called Mr Bell took over operations in 1866. His full name is lost to history, but he hired John David Humphreys as a book-keeper the following year, as the company’s reputation as the colonial government’s preferred chemist spread quickly to Shanghai, Singapore, Tokyo and throughout the Far East.

In 1874, while the going was good, Humphreys acquired controlling shares in the company, making him the sole owner, or taipan – a powerful foreign business executive or entrepreneur during Hong Kong’s colonial heyday.

Meanwhile, in Europe, sales of opium substitutes were becoming increasingly significant, due to the availability of codeine and other narcotic analgesics, the most significant being heroin, following its discovery in 1897.

In those Victorian times it was possible to walk into a chemist and buy, without prescription, substances such as cocaine, arsenic and laudanum. Laudanum was a popular painkiller and relaxant, recommended for all sorts of ailments including coughs, rheumatism, “women’s troubles” and, perhaps most disturbingly, as a soporific for babies and young children. And with 20 or 25 drops of laudanum costing just a penny, it was also affordable.

The 1868 Pharmacy Act attempted to control the sale and supply of opium-based preparations by ensuring that they could be sold only by registered chemists. But this was largely ineffective, as there was no limit on the amount the chemist could sell to the public.

The expatriate population of Hong Kong had more than trebled from 3,000 in 1860 to 10,000 in 1880, and Humphreys imported equipment from Europe to enlarge the production capacity of opium substitutes, for sale in Hong Kong, mainland China and export markets.

The profits were used to relocate the Shanghai branch of the Dispensary to larger premises on the Bund. They also paid for the installation of soda water manufacturing plants in both Shanghai and Manila. Meanwhile, Humphreys was grooming his eldest son, Henry, to take over as the next taipan.

In the UK, young Humphreys completed his pharmacist diploma in 1888 at the School of Pharmacy run by the Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain.

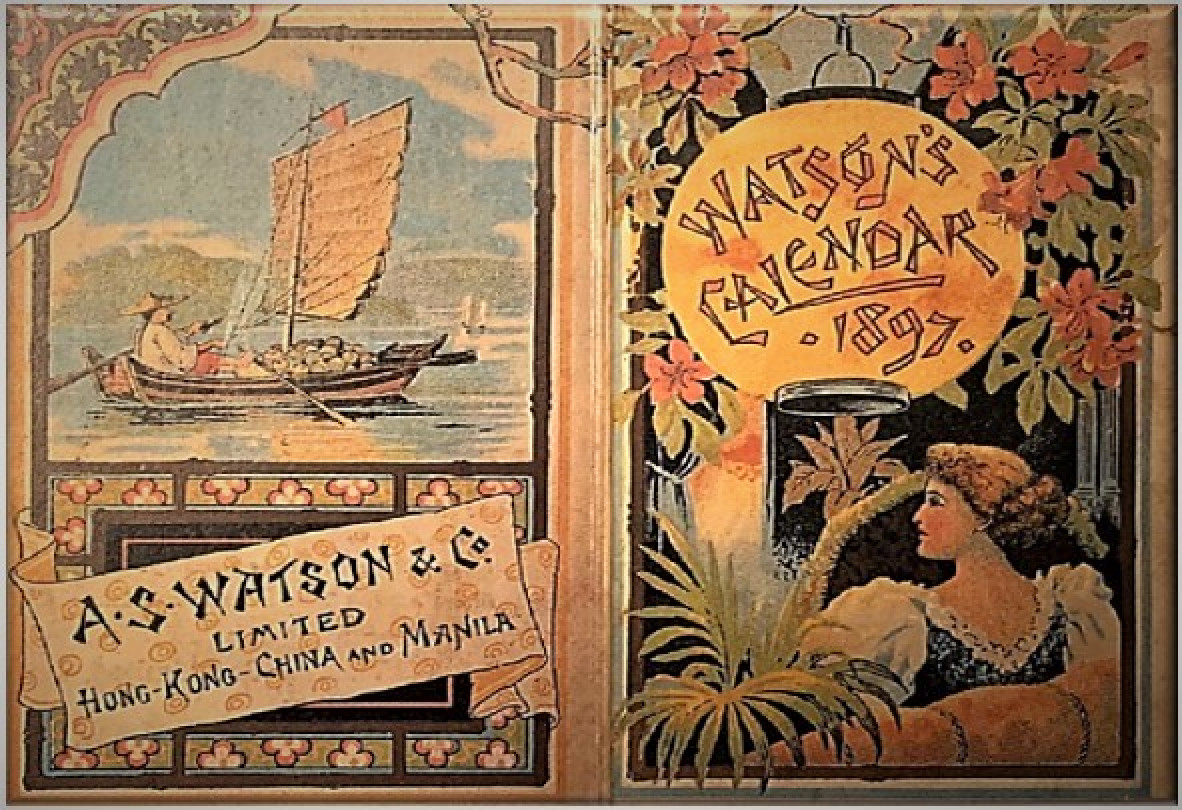

He was just 21. Upon returning to Hong Kong in early 1889, Humphreys’ first assignment was to implement a branding strategy. He achieved this within the first six months, registering trademarks of wines, spirits, and soft drinks, infant food, toiletries and opium substitutes.

After visiting branches in Peking, Canton, Hankow (now a district of Wuhan) and Shanghai in 1890, Humphreys suggested that his father and the A S Watson shareholders invest an additional HK$200,000 to generate consumer demand and improve supply chain management through advertising and promotion of opium substitutes.

Annual demand for opium in that time shot through the roof to over 13,000 metric tonnes – half of which was imported mostly from British India. Between 40,000-60,000 [people], or roughly 25 to 37 per cent of Hong Kong’s Chinese population had become opium smokers after 1880 and this remained so until the close of the 19th century.

Humphreys did not engage directly in the opium trade like his peers Elias Sassoon (1820-1880), Hormusjee Naorojee Mody (1838-1911) or the firm of Jardine, Matheson. As a retail chemist, he launched opium substitutes imported from the UK to replace opium smoking in Hong Kong.

Humphreys came to see Shanghai’s location, at the mouth of the Yangtze River, evolving as the nationwide logistics centre, and he entrusted John Davey as the Shanghai Dispensary manager, and James Jones as assistant, in 1882 to prepare for the roll-out of opium substitutes. In Hong Kong, one of these opium substitutes saw serious spikes in profits – morphine.

In early 1893, A S Watson’s retail and wholesale business jumped after followers of American medical missionary Dr John Kerr were introduced to morphine injections as an “anti-addiction remedy” for “coolies”. The derogatory moniker was a Hindi word used in India and exported to some British colonies that referred to unskilled labourers or porters engaged in heavy lifting work.

Coolies found that they could save more than 80 per cent on highs by injecting morphine, much cheaper than purchasing residual opium scraps collected from used opium pipes. All Western chemists, including A S Watson, had long queues outside their dispensaries each morning for morphine supplies.

The impact on business at the time was such that Hau Fook Hong, the official “Opium Farmer” representing the licensed opium dens, requested the Colonial Treasurer address the loss of opium revenues on May 24, 1893, due to the competition from morphine injections.

Because of this, the 1893 Morphine Ordinance was promulgated on September 23, prohibiting unauthorised use of morphine injections without medical supervision or a prescription issued by a medical practitioner. Watsons, however, continued the export of opium substitutes to mainland China, Formosa (Taiwan) and Southeast Asia well into the first part of the 20th century.

By the time it celebrated its Diamond Anniversary in 1901, Watsons had over 100 retail drug stores outside Hong Kong in mainland China and the Philippines. Of course, these were tumultuous times. The Beijing branch was burnt down at the height of the Boxer Rebellion in the summer of 1901, which caused serious disruption to its retail and wholesale businesses in north China.

During this time, the Shanghai market had become increasingly competitive, with local entrepreneur-owned retail chemists lowering their prices to gain volume share of the opium substitute business. At the same time, European, Japanese and Chinese companies supplied newer and more potent drugs like cocaine and heroin pills.

A downturn in business began in the years leading up to World War I in 1914. Natural disasters followed by the collapse of the rubber futures on the Shanghai Stock Market in 1910 brought economic panic. Many retail pharmacies and wholesalers suffered cash-flow problems and Watsons had to write off significant loans.

Then the eventual Republican revolution on October 1, 1911, shook the market even further, resulting in a drastic 50 per cent depreciation of Chinese silver currency. However, with Watsons’ virtual monopoly on opium substitutes in Southeast Asia, creditors and shareholders had not lost faith in Humphreys, or the future of A S Watson.

Transformation from Colonial Chemist to Global Health and Beauty Retailer: A S Watson, by Patrick Chiu, will be released this month and can be pre-ordered at Bookazine outlets and on bookazine.com.hk.