- Many deadly blazes during the mid-19th century that killed hundreds and destroyed countless homes could have been prevented had the city’s leaders acted faster

Before Hong Kong founded its Fire Services Department, in 1868, even before the British arrived, in 1841, each household would equip itself with a bucket filled with water, marked “do not touch”.

When a fire alarm was raised, nearby householders would rush out with their buckets and either join in the effort to extinguish it or lend their bucket to others, knowing they could claim it back once the fire was out.

But with the building frenzy that followed the British arrival in Hong Kong, it wasn’t long before fires had reached a scale that required more than a daisy chain of water buckets.

During the 1840s, Hong Kong had become not only a trading centre for the British, but also the primary base for its fleet and troops in the region. It was standard practice that the resident garrison would come to the aid of the town during any civil emergency. This meant the army dealt with most fires, which was just as well, since there was no government fire brigade and the police equipment didn’t even run to ropes, let alone buckets and ladders.

But for many stationed regiments, coordinating a response to the alarm – a bugle call from the North Barracks, near the shore – could be difficult. At a fire on October 21, 1845, confusion caused by soldiers unsure of which command to follow made matters worse, and a modest fire became more destructive than it should have been.

The following month, in an attempt to resolve the problem, Major General George Charles d’Aguilar issued a general order specifying that the garrison fire brigade at North Barracks should be first at the scene, supported by other regiments, some of which had their own fire engines.

Fires that could be quickly quenched were one thing, but an uncontrollable blaze – one capable of consuming 458 houses and leaving thousands homeless – was quite another. And Hong Kong did not have to wait long for such a disaster.

At 10pm, three days after Christmas Day, 1851, a fire started in cloth merchant Che-cheong’s shop, in Lower Bazaar, Sheung Wan. By the time the army arrived at the blaze, it was deemed necessary to create a firebreak. A house five doors to the north of the fire was pulled down, but even as it was being demolished, flames jumped to the next road.

Nothing could save the densely packed rows of houses and shops running westwards: the fire would stop when it ran out of buildings to consume. It had already crossed Queen’s Road and was threatening to spread to Tai Ping Shan – today, the area of Sheung Wan south of Hollywood Road – Hong Kong’s most densely inhabited, exclusively Chinese district, home mostly to poor labourers.

The spread to the east was not such a threat to life, but endangered the warehouses and businesses on which Hong Kong’s commercial life depended. Incalculable financial loss would be suffered by both Chinese and European businesses. More firebreaks were required. Buildings were selected for quick destruction and gunpowder brought from the Arsenal.

The operation successfully contained the blaze. However, the explosion in the Queen’s Road buildings had occurred sooner than planned and three senior army officers responsible for laying the fuse, together with two soldiers, who were still in the building at the time, perished.

With so many properties destroyed, both the Chinese and European communities worked to provide relief. Although many of the Chinese were recent arrivals, they had strong networks on the island.

The history (and debauchery) of Hong Kong’s Foreign Correspondents’ Club

Governor George Bonham had ordered two large sheds to be erected to provide free temporary accommodation and food for those affected, but the families, friends and acquaintances of the dispossessed had been so prompt in providing relief that only six people applied for a place.

Many Chinese had connections to the traditional trade guilds that were now organising in Hong Kong. Aside from building up powerful commercial interests, these guilds provided support to both their own members and the wider Chinese community. Firefighting was one practical measure they undertook.

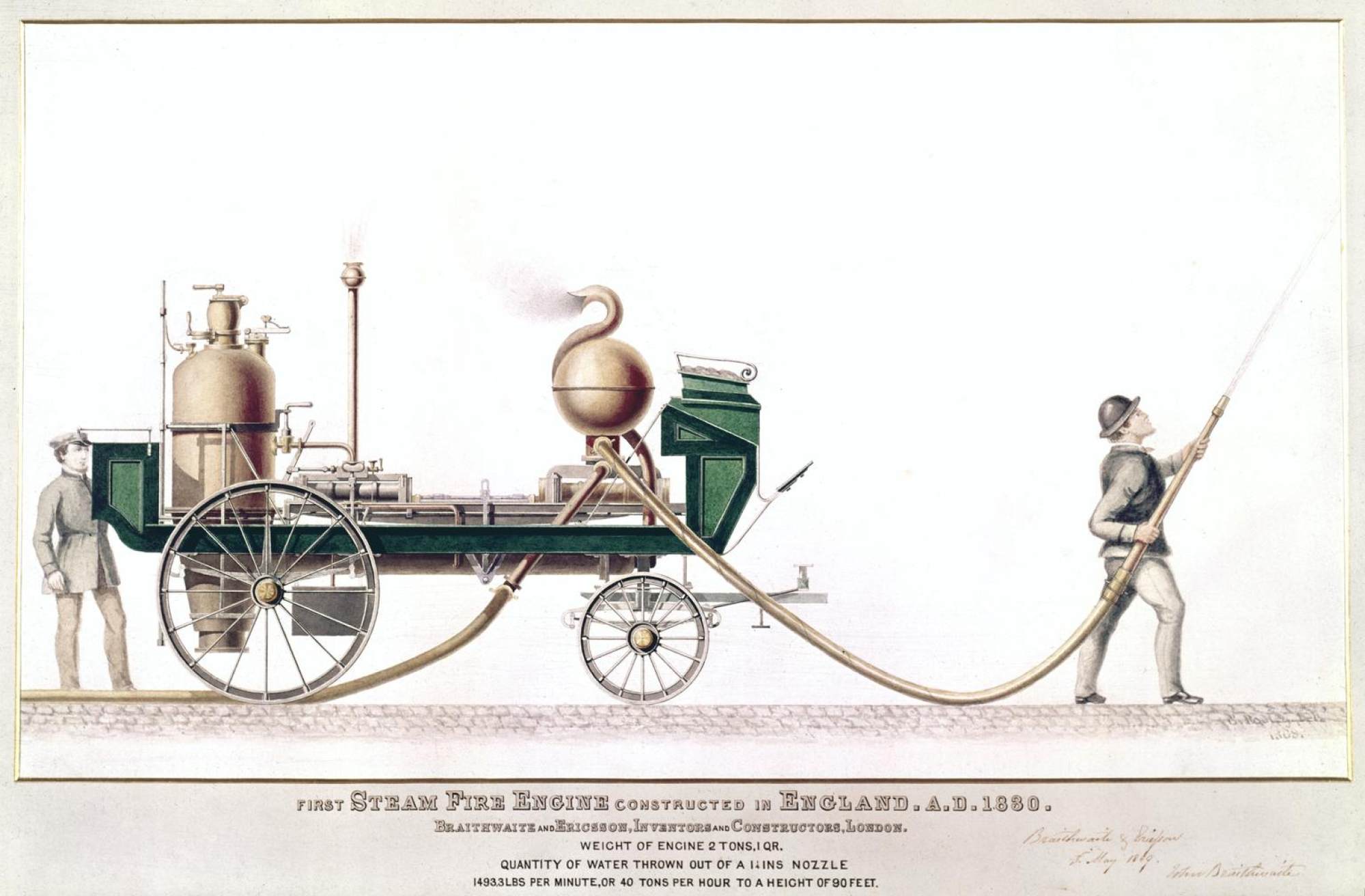

Since they were concerned to protect both property and life, it was these teams that were best supplied with the ladders, rescue ropes and jumping sheets used to free trapped residents. The best-documented guild fire brigade was that of the Nam Pak Hong, formed in 1868, but the Pawnbrokers’ Guild, the Silk Mercers’ Guild and others had purchased small steam-powered fire engines long before that.

Foremost of the Chinese leaders, at least in the eyes of the government, was Tam Achoy. He had lost a good deal of property in the Christmas 1851 fire, but had the capital to use that as an opportunity to rebuild on a larger scale and develop his construction firm, which was responsible for many of the distinguished buildings of the time.

In a sign that Hong Kong was becoming a settled place, Chinese and Westerners, businesspeople and residents alike were all beginning to demand more of the government. All property holders paid rates and police rates, but what, they asked, did they get in return for their money?

In these early years they certainly could not look to a reliable police force to protect them. The pay was so paltry as to attract only the most desperate types, many of whom would be dismissed for drunkenness or neglect of duty before three months had passed. The force’s record when attending fires was lamentable. Aside from having no firefighting equipment, they were more often seen looting properties than protecting them.

The fourth governor, John Bowring (1854-59), had a background in commerce and politics, and was deeply interested in the development of Hong Kong. Seeking to improve the police force, in August 1855 he appointed a commission to draw up recommendations.

One outcome of the commission was that a group of businessmen proposed he should establish an auxiliary force of special constables, which could be called upon in an emergency, and from which volunteers could form a fire brigade. Seeing the advantages of this, Bowring drew up an ordinance recognising this “official” volunteer force.

Two new fire engines were ordered for this purpose, but they had not yet arrived from England when Hong Kong’s next big conflagration broke out in the early hours of February 24, 1856.

It started in a store near Western Market, site of the present Sheung Wan Municipal Services Building. On that windy night, the fire soon took hold and spread across Queen’s Road West, threatening Tai Ping Shan before the combined might of the various – mostly manual – fire engines could make any headway.

Once more, firebreaks were needed, and four men perished when they failed to leave the building selected for demolition before it was blown up. The firebreak did prove effective in containing the fire, but not before it had smouldered for many hours and destroyed 78 houses, causing more than HK$100,000 worth of damage.

The volunteer brigade had been short-lived, and there was still no real oversight in the management of fires. This chaotic state of affairs was illustrated by the response to another fire in Tai Ping Shan at the end of March 1858.

The story of Watsons: from licensed opium dealer to Asia’s biggest pharmacy

The fire had started when residents were cooking rice underneath the staircase of the building where they lived. There was a spill of kerosene and the stairs caught light, the blaze spreading to flammable products in a chandlery (ship supplies shop). From there to the adjoining houses it was a matter of a few minutes for the fire to spread, and soon it was out of control.

Forty-nine houses were burning between Caine Road and Hollywood Road. The two new police fire engines were called into action, with one stationed by the harbour (now Des Voeux Road) pumping seawater and relaying it to the second engine. But the combined hoses proved to be about 15 metres too short.

The Tam Achoy steam fire engine arrived with volunteers to work it, but accessible water soon ran out. The government had built a great water tank above Tai Ping Shan for just such an emergency, and it was full, but with no pipes having yet been laid, it was also useless.

The fire saw four women living above the chandlery trapped and burned to death. Others perished too – eight bodies were found and it was expected that there would be more.

Water pipes, fed by streams and watercourses on the hills around the town, had been laid to government buildings and the military barracks from the early years, and, by 1850, these were also feeding several fire plugs or hydrants – standpipes with one or more secured outlets, into which a fire hose could be screwed.

Some shops had substantial stocks of saltpetre, or potassium nitrate … the principal ingredient in gunpowder. The explosions that resulted when these stocks caught fire, seen from the harbour, lit up The Peak itself

Towards the end of the 1850s, more were being installed, fed by pipes from the hills, bringing water to public areas and the principal roads. But the piecemeal way in which such infrastructure was introduced meant that often the gauge of the pipes was different to that of the fire engine hose, and not all engines carried adaptors.

During the first years of the 1860s, the fires that occurred were small, but three disasters between 1866 and 1868 would see at last a determined effort by the governor to create a properly trained and equipped fire-response force.

The first blaze occurred on the night of October 30, 1866, and was clearly a case of arson: the initial fire was spotted by a policeman, one Inspector da Silva, in an unoccupied house, where a pile of scraps and cotton was burning in the middle of a room.

The house was on Queen’s Road West. Although the arterial thoroughfare was only one block inland from the harbour, no water was immediately accessible, so the inspector could not tackle it immediately. By the time help arrived, the entire house was ablaze and neighbouring properties were starting to catch fire as sparks landed on their overhanging wooden verandas.

When the troops arrived, they had to focus once again on creating firebreaks, particularly as the flames were approaching a large timber yard to the west.

The massive coal store of the P&O Steamship Company lay to the east of the fire, where the company’s floating steam fire engine was able to protect it. The China Mail reported the fire as resembling a giant furnace, a quarter of a mile long, burning on either side of Queen’s Road.

The ruins of the 136 houses destroyed were still smouldering the next evening. Surprisingly, only four fatalities were reported.

The fire was a foreshadowing of the calamity that struck a year later. Once more, it started near the harbour, but closer to the centre of town. A large consignment of cotton had been unloaded that morning into a warehouse on Wing Lok Street, in the easterly part of the road that still had a harbour frontage, and it was there that the fire began.

It was not believed to have been arson on this occasion: both Governor Richard MacDonnell and the English-language newspapers put it down to the casual carelessness of day labourers, all too apt to light a candle or small stove to make food in the dusty warehouse.

Before the fire engines had arrived, it had spread west to the neighbouring Chinese houses. From there, the many little alleys and lanes proved no hindrance to the flames, but were almost impossible to negotiate for even a small fire engine.

A long spell of dry, windy weather had turned most of the external woodwork of these houses into tinder. There was no time to demolish any houses manually, and while some were blown up with gunpowder to create a break, a number of them caught fire anyway.

Added to that, some shops had substantial stocks of saltpetre, or potassium nitrate, a chemical compound with many domestic uses, but also the principal ingredient in gunpowder. The explosions that resulted when these stocks caught fire, seen from the harbour, lit up The Peak itself.

The mysterious Chinese beauty caught smuggling drugs to the US

In the end, the fire would destroy 320 tenement houses and many shops and storehouses over a four-hectare site, stretching south from Wing Lok Street to Jervois Street, and east from Morrison Street to Wing Wo Street. The governor estimated losses at more than HK$1 million – well in excess of the government’s expenditure for the entire year.

Most of these losses were sustained by the Chinese community, and few of the properties were insured. Loss of life, too, was considerable, although the inferno had been such that the total number of fatalities could not be calculated. Both Chinese and Westerners perished, some struck by falling walls and debris days later as they tried to salvage what they could from the ruins.

All the military engines attended the blaze, as well as the two large police manual engines, privately owned engines from the banks and mercantile firms, small steam engines from the guilds of the pawnbrokers and the silk mercers, the naval dockyard engine and others. But who was in charge?

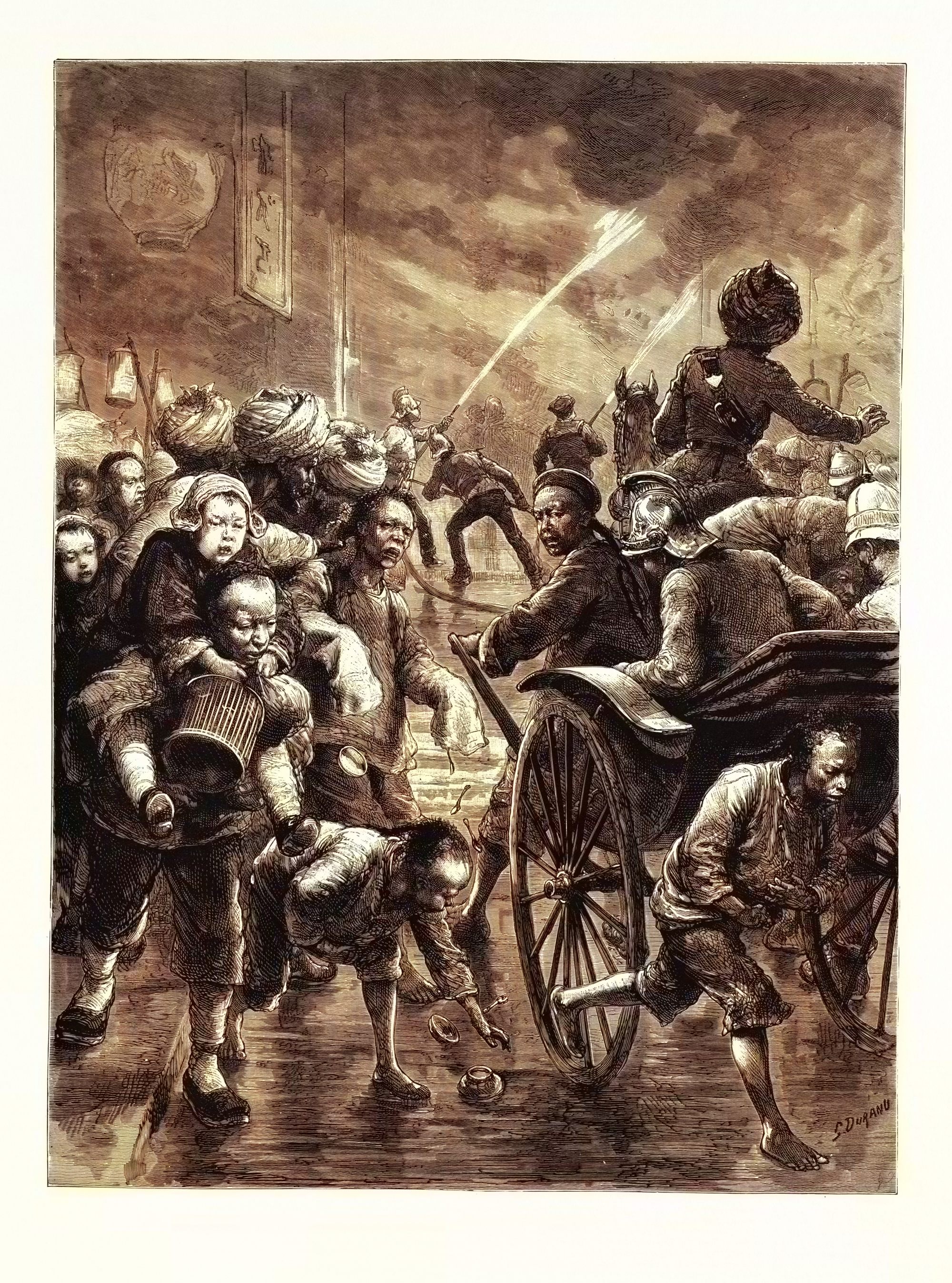

Army and navy officers squabbled about who should blow up which buildings while police constables, trying to prevent looting, arrested householders lawfully removing their own property to safety, and sailors told to help owners rescue their belongings used the opportunity to raid the liquor shops. Hundreds of people came out to see the spectacle, many of them crowding the roads and obstructing efforts to put out the fire.

Governor MacDonnell spent the entire night at the scene, often taking a turn at the engine pumps. He had to return to Government House for a change of clothing at one point, having received a dousing from a mismanaged hose.

The scale and severity of the fire had hardened MacDonnell’s resolve to form a proper firefighting force, following the fire of the previous year, when he had planned for a semi-volunteer force, costs shared between the many fire insurance companies now operating. To his disappointment, he had met with indifference from the firms, and no great interest among the European community to sign up as unpaid volunteer firemen.

How ‘father of the fishermen’ made Hong Kong dragon boat racing famous

This time, he approached prominent Chinese businessmen who expressed themselves keen to do all they could to make Hong Kong a safer place, and undertook to persuade employers to allow volunteers from their workforce to train and serve in the brigade, even offering to pay for one of the two steam fire engines MacDonnell would order.

The governor happily agreed that this engine would be operated by the volunteers, and on the day MacDonnell wrote to tell the Colonial Office of his plans, the businessmen had given him a substantial deposit for the machine. By June that year, MacDonnell had appointed Charles May, the head of the police force, as the first superintendent.

It was his job to plan how the brigade should operate, and select about 100 men from the police who he judged most fit for the work. May was swift to devise methods of training and sent a requisition for equipment and helmets.

While Superintendent May was still the Hong Kong Fire Brigade’s sole member two fires broke out, in August 1868, and although they were nowhere near as destructive as that of the previous year, they demonstrated to the government and the public the necessity of a functioning fire brigade.

The first blaze, at the corner of Wellington Street and what was then Pedder Hill, was the smaller emergency but still jumped swiftly from house to house by the ever-flammable overhanging verandas. Five days later, an accidental fire, again started under a staircase, consumed a shop on the corner of Jervois and Hillier streets.

Nineteen people perished, being trapped by the speed at which the fire destroyed the staircase. Over an area of 4,000 square metres, 72 further houses were ruined, and other lives lost.

How Chinese forced to run online scams in Cambodia can pay with their lives

The new machines had not yet arrived, but still the usual variety of independently owned engines were brought to the site. Even still, the big P&O land steam engine, the one that might have made an impact on the fire, was damaged on the way, when a street drain collapsed under its weight.

Ramshackle as the conditions were, this was to be the last major fire on Hong Kong Island to be tackled without formal leadership.

And while the various organisations would continue to send their fire engines out in their own interests, all came under the supervision of the head of the Hong Kong Fire Brigade, a body of men wearing their helmets with the service’s insignia prominently displayed, as they still do today.