- In 1903, Katharine Augusta Carl was invited to paint the first portrait of China’s feared empress dowager, gaining unprecedented access to the imperial palace

At 11 o’clock on a warm summer’s morning in 1903, 38-year-old artist Katharine Augusta Carl was ushered into the throne room of the Summer Palace, on the western outskirts of Beijing.

67-year-old Empress Dowager Cixi, who had effectively controlled China for more than 40 years, entered with her chief lady-in-waiting and interpreter Princess Der Ling, an ambassador’s daughter who had spent time in Europe and the United States.

By Cixi’s side, as always, was the Guangxu Emperor who, though technically the 10th sovereign of the Qing dynasty, acquiesced in all matters to the empress dowager.

Dressed in her ceremonial gown, Cixi was assisted onto the Dragon Throne by her attendant eunuchs while the ladies of the court fussed with her robe and headdress and Carl prepared her easel next to a table with paints, brushes, rags, turpentine, palette knives, and all the other tools of the portrait painter’s trade.

Positioned and comfortable, the two women eyed each other across the room. The empress dowager nodded, and the painter made her first stroke on the blank canvas.

Over nine long months several portraits would be attempted. The main life-size image was to be China’s sole entry in the Fine Arts Pavilion at the 1904 World’s Fair, in St Louis, Missouri, and presented thereafter to US president Theodore Roosevelt.

Today it hangs in Washington’s Smithsonian museum. But the story of how an American artist came to be invited to the Qing imperial court to paint the most famous and reclusive woman in China is less well known.

Sarah Pike Conger, the wife of the American ambassador to China, Edwin H. Conger, heard Carl was in Shanghai visiting her brother, who worked for the Chinese Imperial Maritime Customs, and knew of her growing reputation as a portrait painter.

Pike Conger also knew that no likeness of Cixi, not painting nor photograph, existed. American and European newspapers regularly portrayed the dowager as either a conniving witch or hectoring dragon lady.

Hers was the only Western art that adorned Mao Zedong’s personal rooms

The Congers were important figures in Beijing’s diplomatic circles, having survived the Boxer rebellion at the turn of the 20th century and the resultant siege of the legations. Pike Conger had become known as the “grand dame” of the Legation Quarter, defying her husband by making friends with the empress, who was vilified by the foreign community for having encouraged the Boxer “rebels”.

Pike Conger devised the notion of persuading the empress dowager to have her portrait painted for the first time, and suggested Carl as the ideal artist having studied painting at Tennessee Female College and then in Paris. She specialised in portraits and had exhibited in London, Paris and Chicago. Perhaps most importantly, she was already in China.

The bureaucratic wheels turned slowly but, after much consulting of astrological almanacs, Carl was told to present herself at the Summer Palace on August 5, 1903, prepared to begin painting at 11am. She agreed, and set out for Beijing.

In those days it took several hours to journey from the American Legation out to the Summer Palace.

A Chinese honour guard met them outside the city walls to escort them 25km to their destination, and Carl and Pike Conger, accompanied by a Marine Guard, headed west.

At the Summer Palace’s Imperial Entrance the party was greeted by the stern-faced Li Lianying, the court’s powerful chief eunuch. Li had arranged red velvet-covered chairs, each carried by six bearers. They entered the palace confines, passed through successive halls, courtyards and gardens, and eventually into the empress dowager’s throne room.

Cixi’s chosen gown was imperial yellow silk, embellished with a wisteria vine pattern, embroidered with pearls and fastened with jade buttons. For adornment the empress wore a string of 18 enormous pearls. At her throat was a cravat, embroidered in gold and decorated in yet more pearls.

Her black hair was centre-parted and coiled beneath a traditional winged Manchu headdress decorated with flowers, jewels and a tassel of even more pearls. Jade bracelets, rings, as well as fingernail guards adorned each hand. Barely five foot (1.5m) tall, Cixi sat on cushions wearing Manchu shoes with six-inch-high soles.

Carl jumped when all 85 clocks in the throne room chimed in perfect unison announcing 11am, the appointed time to commence. Carl recalled that, as she raised her charcoal, “My hands trembled!”

Li, Der Ling and Pike Conger watched attentively. Cixi stared straight at the artist.

Carl’s initial task was to block in the whole figure of the empress and attempt to capture some likeness. After a few hours, Cixi dismounted the throne declaring the day over.

She inspected Carl’s work, passed no comment, but invited the painter to reside at the palace so they could sit and work at their leisure. Carl took this as a positive response.

That evening Carl, Pike Conger, Der Ling and the chief eunuch all dined together. The empress and emperor (who appeared to Carl as a young man but was in fact 32) always dined alone but did join the others afterwards to watch some Peking opera.

Following the performance Pike Conger rose to return to the city, said goodnight to the empress and left. Thus Carl became the first foreigner to ever be domiciled in a Chinese royal palace “since the times of Marco Polo”, and the first ever to reside within the Summer Palace’s ladies’ precincts.

She was assigned quarters next to the throne room, unoccupied since it had been badly damaged by foreign troops in the aftermath of the Boxer rebellion.

Carl’s lodgings comprised several rooms with marble floors, carved partitions and corridors. There were two sitting rooms, a dining room and a bedroom, all decorated with Chinese art and calligraphic scrolls. To accommodate the American, a Western-style couch with silk cushions was provided.

Woken at five o’clock the following morning, Carl discovered the empress was an early riser, taking breakfast and beginning her second day working with Cixi.

The empress asked through her interpreter if Carl “felt ready for work” and offered her a cup of tea. They began, though after only an hour Cixi declared herself finished for the morning.

She lunched, napped and then granted Carl another hour-long sitting. Once again, she examined Carl’s work and seemed pleased.

And so the first portrait slowly moved towards completion. Such a routine gave Carl ample time to explore the Summer Palace and its environs. The weeks passed and familiarity set in.

At times Cixi would break from the sitting to order eunuchs to sing for them. She asked Carl to join her on the imperial barge, pulled under successive camelback bridges to Kunming Lake. She was invited to walk with the empress and her many dogs (Chinese pugs mostly), or to take part in apple-picking trips in the palace’s extensive orchards.

Over the next months Cixi would switch between sitting for Carl and then leaving to deal with matters of state, her solo lunches or a siesta. Carl could not wander far, as Cixi might suddenly return unannounced and offer herself to the artist again.

When Cixi would leave the throne room for the day, all of Carl’s tools were gathered up and stored in a locked room. A specially constructed screen covered the canvas to protect it. Even uncompleted, it was already, Li declared, a “sacred object”.

Once the first portrait was completed, a second was begun – similar to the first only with a background of bamboo, and Cixi holding a round Chinese fan. Then a third, portraying the empress in a green robe.

The fourth portrait was to be destined for St Louis. By this time Cixi and the court had relocated from their summer retreat to the Forbidden City. A large hall was found for Carl and the sittings resumed much as before.

A carved teakwood throne was selected and, while her accessories remained virtually constant, Cixi’s thin summer gown was exchanged for a fur-lined winter one. The empress suggested the addition of a screen adorned with phoenix decorations and an embroidered shawl.

Carl sketched an outline and presented it to Cixi, who approved. If this was to be the portrait that would travel to the World’s Fair then it had to be grand. A canvas six feet by 10 was demanded.

A bamboo frame was constructed, but nobody knew how to stretch such an immense canvas. Carl had to climb a six-foot-high stool as eunuchs stood around the base of the frame, handing up pincers while the artist stretched the canvas herself.

Two problems now arose. Logistics demanded the portrait arrive in St Louis by April 1904 to coincide with the fair’s opening, and, Carl was informed, there was no other canvas of such size in China. There could be no experiments; she had to get it right the first time.

As winter set in, the empress sat for shorter and shorter periods while Carl worked alone late into the night, “like an artisan, finishing so many inches a day”.

The portrait of Cixi that Carl finally produced is stunning even today, and would have been more so in 1904, when no representation of Cixi had been seen. The image is opulent and flattering, full of colour and texture.

However, despite her training in the French style of portraiture, Carl’s likeness of Cixi was required to follow many Chinese conventions, firmly insisted upon by the Foreign Ministry. For instance, there were to be no shadows or noticeable perspective, everything had to be painted in full light.

Carl claimed this meant the portrait lost a degree of the picturesque charm she had initially hoped for. These strictures, “the iron fetters of Chinese tradition”, annoyed her.

Carl later claimed she had struggled to render the background phoenixes while the insistence on the absolute centrality of Cixi in the picture and the two side vases being at precise equal distances from the throne were tough demands.

The painting of the Empress Dowager by an American girl must have been a difficult job. A line too unhandsome and off would go one’s headA report covering Cixi’s portrait in the Macon News of Georgia

Four o’clock in the afternoon of April 19 was judged the most propitious moment to complete the portrait. As the date approached, Cixi regularly visited Carl’s studio, commenting on small details and colouring. Occasionally Cixi would consider a pearl or jade ornamentation not quite right, change it, and Carl would have to repaint.

Pike Conger and other senior diplomats’ wives visited from the Legation Quarter to admire the work and offer encouragement.

The final task was to place the finished portrait within an elaborately carved camphor frame that made the portrait 16 feet high and weigh half a tonne. Unveiled to the court, the portrait was first photographed by a young man called Xunling, recently returned from Paris, where his father was the Chinese ambassador.

Soon afterwards Cixi would deign to be photographed by him as well – her first photographic portraits.

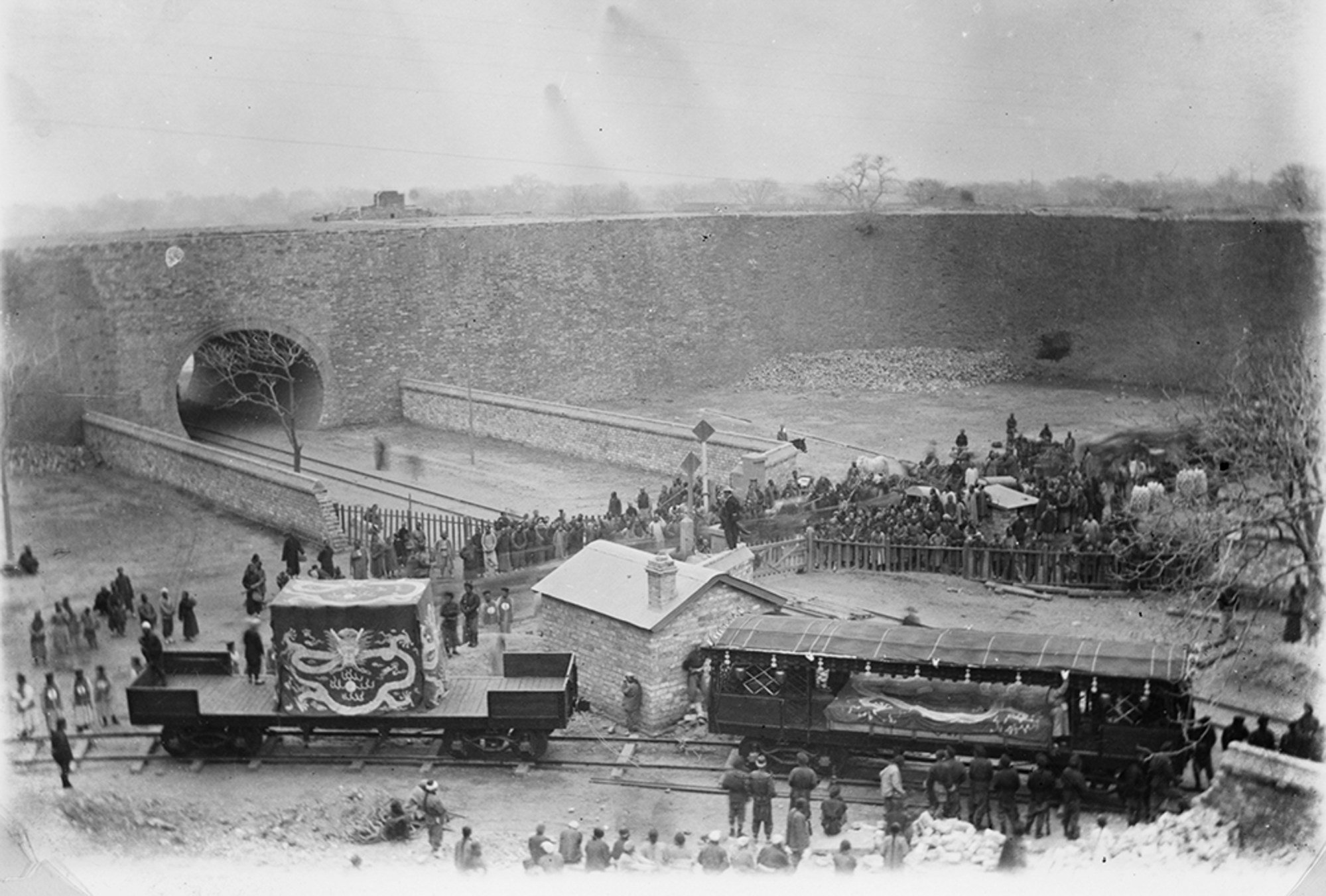

The portrait finished and framed, it now had to be shipped to the US. But there could be no ordinary pack-and-post for an image of the empress of China. The painting was transported from Beijing to Tianjin by a privately commissioned train carriage, enclosed in a specially designed wooden box with ornate bronze handles.

The locked packing crate itself was wrapped in red and yellow silk embroidered with the double dragon motif. From Tianjin, the portrait went to Shanghai by boat, and from there to San Francisco by steamer.

The almanacs were consulted once more, and at 4pm on June 19 the portrait was unveiled in St Louis by Prince Pu Lun, “Minister to His Imperial Presence”, Chinese ambassador to the US Liang Cheng, and the Chinese government’s commissioner to the fair, Wong Kai Kah.

The assembled crowd toasted the Empress Dowager Cixi with champagne, but the initial reviews were not great. The New York Times fixated on the portrait’s immensity and Cixi’s elaborate hair styling. But Carl’s artistry was praised, with The Arkansas Democrat calling her “a portrait painter of rare ability”.

Politically, the American press were not swayed by the portrait. It didn’t, as Pike Conger had hoped, sooth adverse opinion regarding China in general, or the empress in particular. The newspapers claimed Cixi had forced Carl to paint her as more youthful, beautiful and less harsh.

The Macon News of Georgia sent a columnist to St Louis to see the portrait, and he wrote, “the painting of the Empress Dowager by an American girl must have been a difficult job. A line too unhandsome and off would go one’s head”.

Carl denied these accusations and eventually, though she knew the Forbidden City would see it as indiscreet and a breach of etiquette, she told her own story in With the Empress Dowager of China, published in 1906. It’s a generally uncritical account of her experiences and a flattering portrait of Cixi, stressing their good relationship.

Princess Der Ling published Two Years in the Forbidden City in 1911, three years after Cixi’s death, claiming the empress was often annoyed by Carl’s insistence on her sitting for the portrait, tried to avoid her and repeatedly asked Der Ling to dress up and take her place.

Cixi decided the portrait should be presented to Roosevelt after the close of the fair, so it was packed up again and sent on to Washington. Roosevelt later gave the portrait to the Smithsonian, which then lent it to a museum in Taiwan in the 1960s.

It remained there for 40 years before returning to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art, where it has recently undergone a complete restoration.

‘I was screaming for help’: the Cambodian brides trafficked into China

Katharine Carl stayed on in Beijing after completing her portraits, moving back to the Summer Palace in April 1904, painting in a studio specially created for her and enjoying the solitude and beauty of the grounds. Her connections remained, and she continued to paint prominent diplomats as well as a study of the last emperor, Puyi, of whom she was fond.

She finally returned to America in 1931, by then in her late 60s, and continued to paint portraits in her New York studio, on West 57th Street. She remained a popular portraitist and had no trouble securing commissions, though her work never again gained the fame and notoriety of her Empress Dowager Cixi portrait. She died in New York in 1938.

Carl wrote of that first year in the Summer Palace, painting Cixi, that “it was by far the most charming experience of my life”.