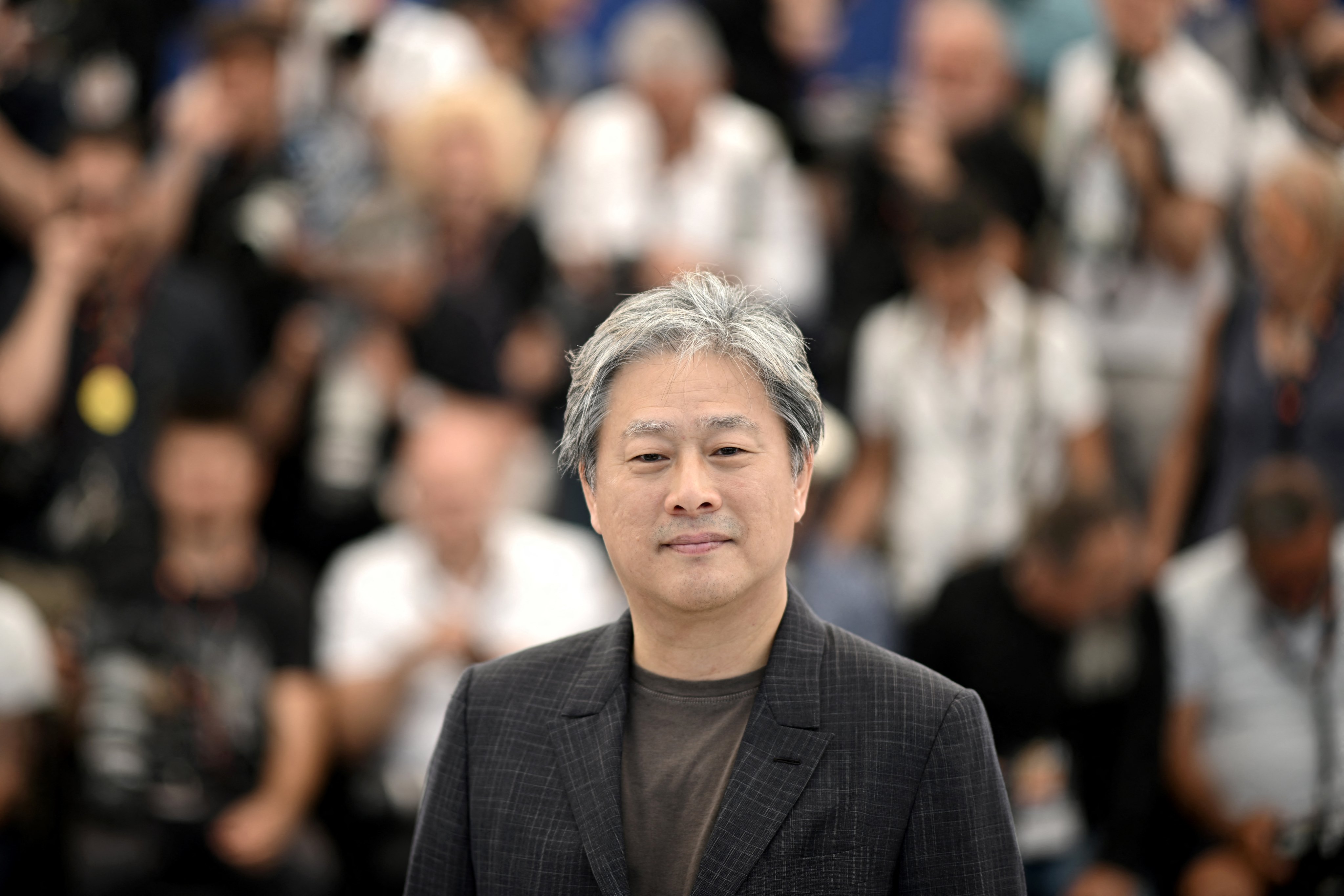

- Park Chan-wook, a Korean filmmaker who vaulted to international attention in 2003 with Oldboy, talks about his latest movie, Decision to Leave, and his career

Park Chan-wook knows he has a reputation for shock.

The South Korean filmmaker vaulted to international attention in 2003 with Oldboy, a lurid, exhilarating revenge drama about a man inexplicably held prisoner by an unknown captor for 15 years, then just as inexplicably set loose.

His subsequent work has ranged from a romantic comedy set in a psychiatric ward (I’m a Cyborg, But That’s OK; 2006), to a perverse family portrait (his first and so far only English-language film, Stoker; 2013), to the 2016 lush erotic thriller The Handmaiden, set in Japanese-occupied Korea.

Park, who is currently directing an HBO series based on Viet Thanh Nguyen’s 2015 novel The Sympathizer, spoke through an interpreter about being a filmmaker who has always been interested in the mechanics of cross-cultural communication.

“When you’re having a conversation, it’s not just about the definition of the words,” he says. “It’s only when the emotion kicks in that you actually get a full picture of what a person is conveying.”

How Oldboy director Park Chan-wook finds beauty in brutality

You are an Alfred Hitchcock fan. Is it fair to say that Decision to Leave is your Vertigo?

“There are plenty of similarities, from the bifurcated structure, to the mysterious wife and dedicated cop, to the fear of heights. When you put it like that, it sounds like all the puzzle pieces coming together, but it wasn’t my intention.

“The fear of heights doesn’t really come from Vertigo – it comes from my own fear of heights. What is very similar is the two-part story structure where, in the second part, time has passed. The man who was shattered reunites with the woman, who has now turned into someone totally different. I realised that the structure itself is so cliché, so typical of noir films.

“At the end of the day, you’re bound by the genre. To get beyond that, I decided to add a new section that turns from a mystery into a love story.

What struck you about Hitchcock’s film?

“That scene where the man is driving through the streets of San Francisco and following the woman. It really felt like being sucked into a daydream.

“Also the moment when the woman is sitting in the museum and we notice the resemblance of how she tied her hair to the woman’s in the portrait, that element of visual motif when you figure out the connection between what seemed like irrelevant people or objects.

“When I was growing up, we didn’t go to cinemas a lot. Instead, every weekend, the newspaper would say which movie would be playing on television and I’d wait with an excited heart with my parents for that.

“What I watched on TV at the time was mostly older French films or classic Hollywood movies. Of the Hitchcock films, I remember my mother liking Rebecca [1940]; she liked those romantic movies.

“I also remember my father saying he enjoyed North by Northwest [1959] – that he didn’t know what it was about but enjoyed it regardless.”

I developed a tendency, subconsciously, to look down on Korean films until my first year of collegePark Chan-wook, director

So no Korean films?

“There were good Korean films and films that did well commercially, but I wouldn’t say the 1970s and 80s were particularly a golden age of Korean cinema. I developed a tendency, subconsciously, to look down on Korean films until my first year of college, when I came upon Kim Ki-young’s Woman of Fire [1971].

Were there any Japanese films you wished you could have seen earlier or ones that became an influence when you were able to watch them?

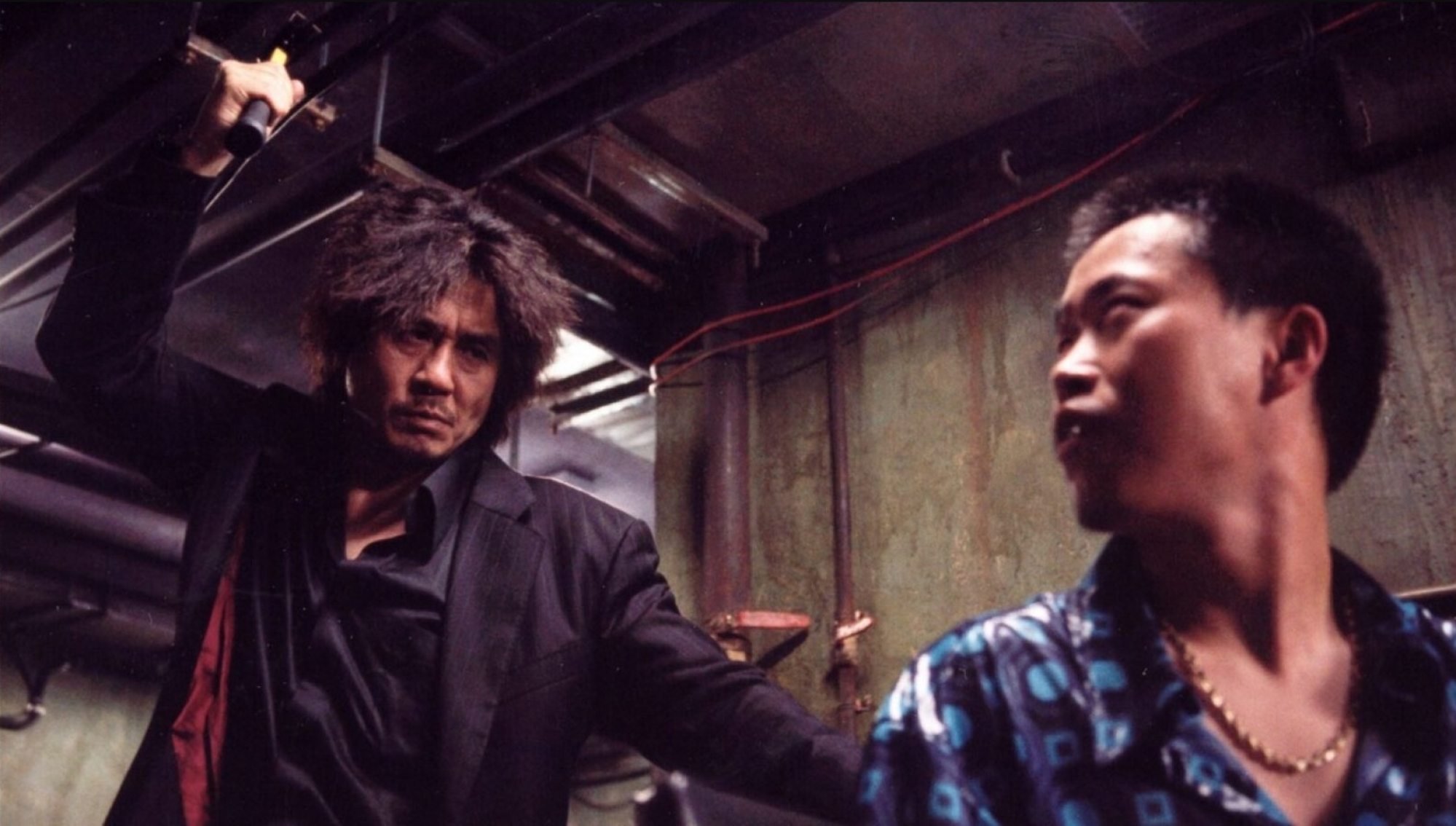

Arguably, Oldboy was the first film of yours to receive attention in the West. It has several famous sequences that linger in the mind; the scene where Choi Min-sik’s character eats a live octopus is on a level of its own, and the single-shot scene in which his character fights his way along a hallway past a group of hired thugs has inspired imitators.

Do you feel your work is perceived differently abroad because of Oldboy when it comes to expectations of extreme content?

“There’s definitely something like that. A lot of people still say, ‘That’s my favourite film.’ With that fight scene, I just wanted to try something different from the same old action scenes I’d seen before. The octopus was the result of my search for the right expression of the character’s loneliness and fatigue. I had no idea it would become such a famous scene.

“You never know what my next film will be. It might be more violent than Oldboy. Who knows?”

Oldboy’s Choi Min-sik to star in Disney+ K-drama King of Savvy

Decision to Leave almost feels like a reaction to that.

“I didn’t make Decision to Leave so I could get rid of such impressions. There’s no, ‘Oh, this is a new chapter and a new era, and I’m moving on.’ Decision to Leave is about characters who conceal their emotions.

“In order for the audience to understand the hidden emotions that are going on, they have to observe the delicate changes of their facial expressions, which is why I got rid of elements such as violence and nudity that might take them away from that. This was not me trying to say, ‘Oh, I can make softer movies, too.’”

You have said that Oldboy changed how you approached female characters in your films.

“In Oldboy, the female character had to end the story without knowing the truth about what’s been going on. And in Joint Security Area [2000], compared to the male characters, the female character doesn’t feel as human or as dynamic.

“I reflected back on this, and that’s why Lady Vengeance [2005], which I made after Oldboy, had to be about a woman, and the actress in Joint Security Area, Lee Young-ae, had to play the lead.”

Oldboy director uses iPhone 13 Pro to make short film for Apple

It seems the second half of Decision to Leave is as strong a reversal as the reveal that the characters in Oldboy were a father and daughter. You graduate from the noir genre, and you move away from the male gaze as well.

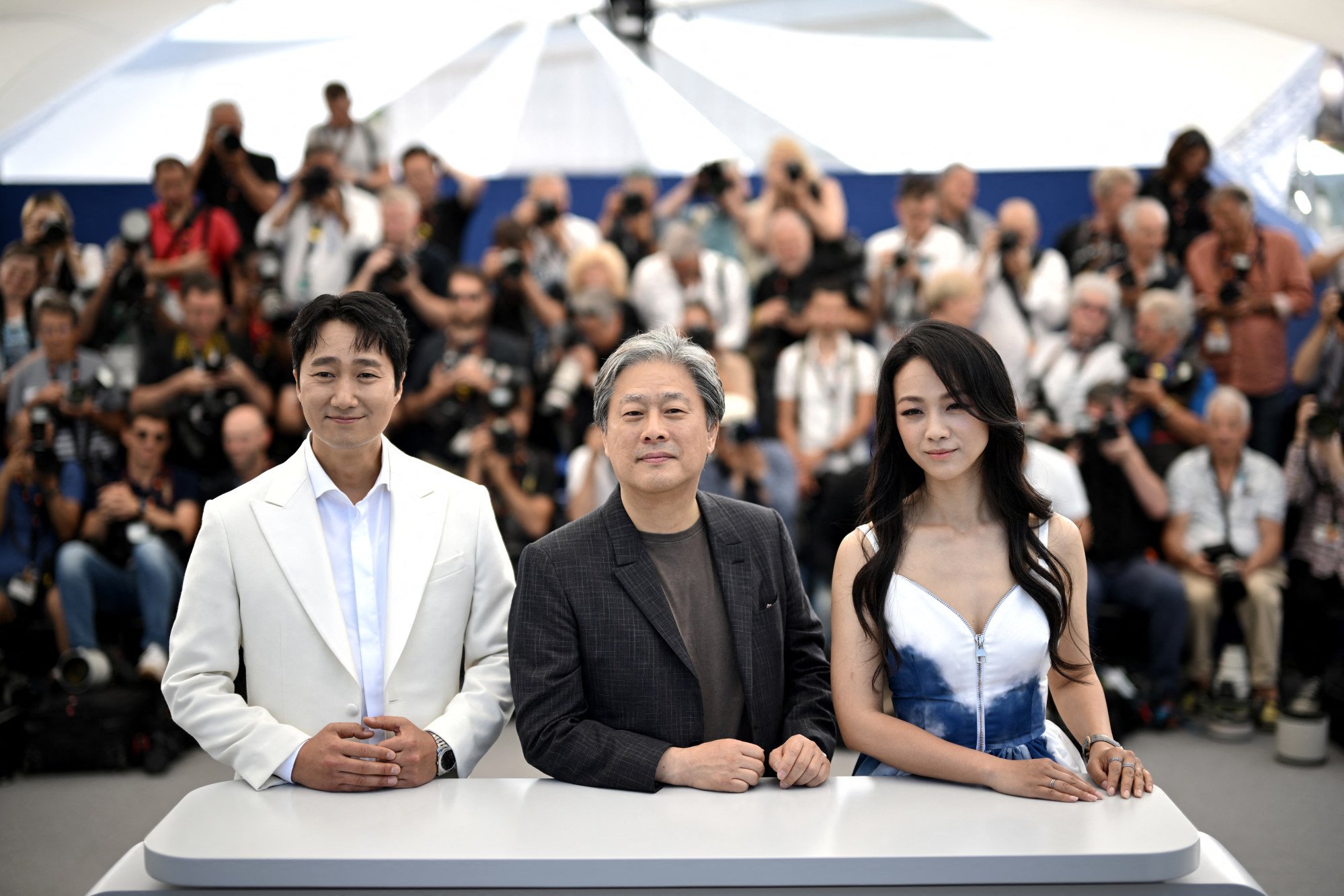

In part two, Tang’s character, Seo-rae, does not merely make an appearance as the object of the man’s perception. We see scenes of her alone. The woman is the one observing the man. How did you end up casting her?

Her character has a particular fondness for historical K-dramas.

“I wanted Seo-rae’s expressions to sound very classical and elegant, and I thought about how a Chinese person living in Korea would learn Korean. She would learn Korean by the book; she wouldn’t pick up colloquial terms.

“To reinforce this point, she watches period dramas, so it’s almost like hearing a foreigner who has learned English through Shakespeare plays.

“The drama we see on the television in the film is a fake one that I made myself because I wanted to have scenes where Seo-rae watched it so many times that she uses a quote from that exact drama when speaking to the detective, Hae-joon.”

The 25 best Korean movies of the 21st century

Would you say languages and language barriers are a particular interest of yours? In your last film, The Handmaiden, whether a character spoke Korean or Japanese said a lot about their situation.

“I am interested in such issues. Even in Lady Vengeance, we see a mother-daughter relationship being hindered by a language barrier where the mother has to use a dictionary to talk to her child. In Joint Security Area, which takes place around the demilitarised zone, there’s that difference between North Korean and South Korean.

“In Decision to Leave, there are complex elements that come out of the differences in language. Seo-rae is proficient in Korean, but when she hits a block, she has to turn to her translation app. When I first discussed this idea, many people objected because the audience has to wait while Seo-rae is talking in Mandarin. You can tell she’s desperate from her expression.

“The audience may be curious but may not have the answer immediately. Some may say this is a bad thing. But I’m the kind of person who would say this is a good thing.

“I also heard a lot about how the film was quite long. Others told me that if we got rid of that translating bit, that could have made the film shorter. I loved the translation parts. The frustration the audience feels parallels how Hae-joon is feeling.

“Seo-rae is so heated, and you really want to know what she’s saying. The AI-like voice is completely flat and dry, and I purposely chose a male voice so it feels more emotionally distant.

“When the audience is hearing this AI voice, they feel a big sense of something lacking, and to satisfy that, they have to combine what they watched earlier with the meaning of what the translation app is saying. They get to experience a more active form of movie watching.”

Bong Joon-ho on Parasite, and getting his way with Weinstein

Decision to Leave is South Korea’s submission to the Oscars this year – the first time a film of yours has been chosen. Do you share your fellow director Bong Joon-ho’s feelings that the Oscars are a “very local” affair?

“As for me, well, first things first: I’m a showrunner for The Sympathizer, so I’ve been very busy. But still I’m trying my best with awards campaigning. The director really has a responsibility toward the cast and the crew, as well as to the investors who are a part of this film.

“All directors think of their work as their child. I really want to see my child get loved and be watched by more people, and I would feel an extreme amount of guilt for abandoning the opportunity to make that a possibility.”

Have you seen the one film of yours that’s been remade in the United States so far – Spike Lee’s 2013 take on Oldboy?

“I did watch it, and I was left with this very curious feeling. The story was similar, but the little details were completely different. Among the obvious differences are the setting (New Orleans), the antagonist’s backstory (there’s a villainous father), the ditching of hypnosis as a plot device, and the ending (less messed up).

So it looked familiar but at the same time unfamiliar. The film itself was meant to look surreal, but I think it felt extra surreal to me as the original filmmaker.”

Squid Game star on show’s Emmy win and how K-cinema attained global clout

There has been a tendency in Western media to group different Korean cultural breakthroughs together – to write about Parasite along with BTS and Hwang Dong-hyuk’s show Squid Game.

What does it feel like to you as an artist to have your work been seen through the lens of an overarching national brand?

“I understand why you asked that question, and I think I would’ve asked the same question if I were in your shoes. It’s just that I don’t really have much comment. I’m working as I have before.

You were among the thousands of artists revealed in 2016 to have been blacklisted by the administration of former South Korean president Park Geun-hye. This meant being blocked from receiving government art subsidies, either because of political leanings or as retaliation for criticism of Park’s regime.

What was it like to find that out? Did it affect your ability to get work made and seen?

“The system to support Korean filmmakers was established by the left and the progressive party, and the conservatives really exploited it. The government provides seed funds for films, then companies provide the rest of the money – so, naturally, these funds are influenced by the opinions of politicians.

Can BTS help South Korea edge out Saudi Arabia to host the 2030 World Expo?

“I had a proposal for a film that got rejected, and only after everything had come out did somebody who was involved with the funding process tell me they had to reject it because of the government. But because a blacklist isn’t public, it’s very hard to provide evidence for what’s really going on.

“The mechanism is discreet collusion. They’re not saying things out loud; they’re looking at each other and trying to feel how the other person is feeling. There’s no explicit email that says, ‘You shouldn’t hire this or that person.’

“My brother, Park Chan-kyong, is a multimedia artist whose work delves into the complexities of South Korean society, who combines art and videography in his works. He had these documentaries that he’d applied for funding for and didn’t get.

“I assume this is also because he, like myself, leans more politically left. But of course, we have no evidence to prove it.”

Do you consider your films political?

“It depends on the work. Joint Security Area and Sympathy for Mr Vengeance [2002] are political films.”

Why Sympathy for Mr Vengeance?

“Because it was a film that tackled class struggle. It portrays how even if a capitalist has good intentions, they are not free from this struggle. The Handmaiden is also political but in a different sense of the word.”

K-dramas have a rage problem, but are the viewers to blame?

Yes, and the fact that some of the characters are Japanese feeds into the power dynamic of the period. In Decision to Leave, Tang’s character is Chinese; did that affect how you thought about the power dynamics of the main relationship?

“People have interpreted it as a statement on the relationship between Korea and China, though I didn’t intend that to be the case. Regardless of the country, I think any foreigner tends to feel small in their unfamiliar environment.

“They sometimes feign even more confidence because they don’t want to feel that way. But all portrayals can have a political meaning behind them. Even if a work was not made with ideology in mind, it’s open to interpretation by the public – which, I think, is the right direction.”

What elements do you think make a good political film?

“Every film obviously tells the story of individuals. Whether it makes a good political film depends on how hard it tries to make an observation on societal structures. The claims it makes should not be conveyed in words but in the plot and in cinematic form. This is where the difference lies between a political film and propaganda.”

Have your own politics evolved? Do you think you’ve become more or less radical?

“I’ve been disappointed by radicals countless times throughout my life, but I was never disappointed by conservatives because I didn’t expect anything from them in the first place.”