- After arriving in Beijing as a missionary, Helen Fette introduced art deco carpets and safer, sanitary labour standards to revolutionise the Chinese rug trade

At the turn of the 20th century, any discerning American home whose inhabitants displayed “taste” had an Oriental rug, invariably a Chinese one.

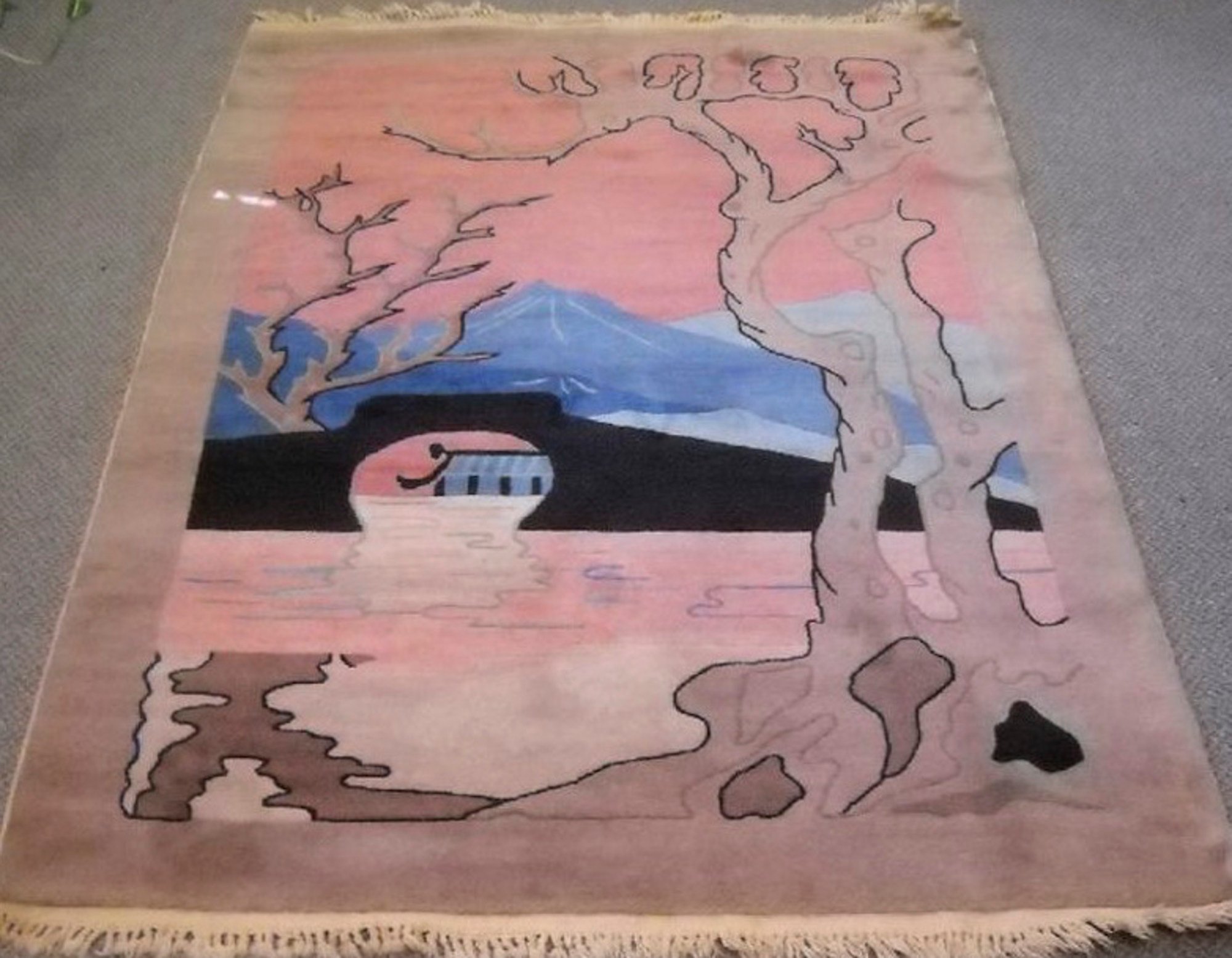

But by the late 1920s, tastes were evolving and, while there was still a great appreciation for traditional patterns and the skilled weaving of Chinese pieces, there rose a desire for rugs that incorporated the new vogue for abstract designs and more vibrant colours.

One Chinese company sought to assimilate these two desires, marrying traditionally woven carpets with new avant garde designs – the Fette-Li Rug Company of Beijing and Tianjin.

Founded in 1921, the firm was a coming together of a highly skilled rug manufacturer – Li Mengshu – and an American entrepreneur living in Beijing, Helen Fette.

As well as exporting rugs to the United States, Fette introduced art deco designs to catch the eye of customers in the US and modern Chinese cities such as Shanghai. Fette and Li used advanced dyes, insisting, too, that Fette-Li be a model workplace in an industry plagued with bad, sometimes fatal working conditions.

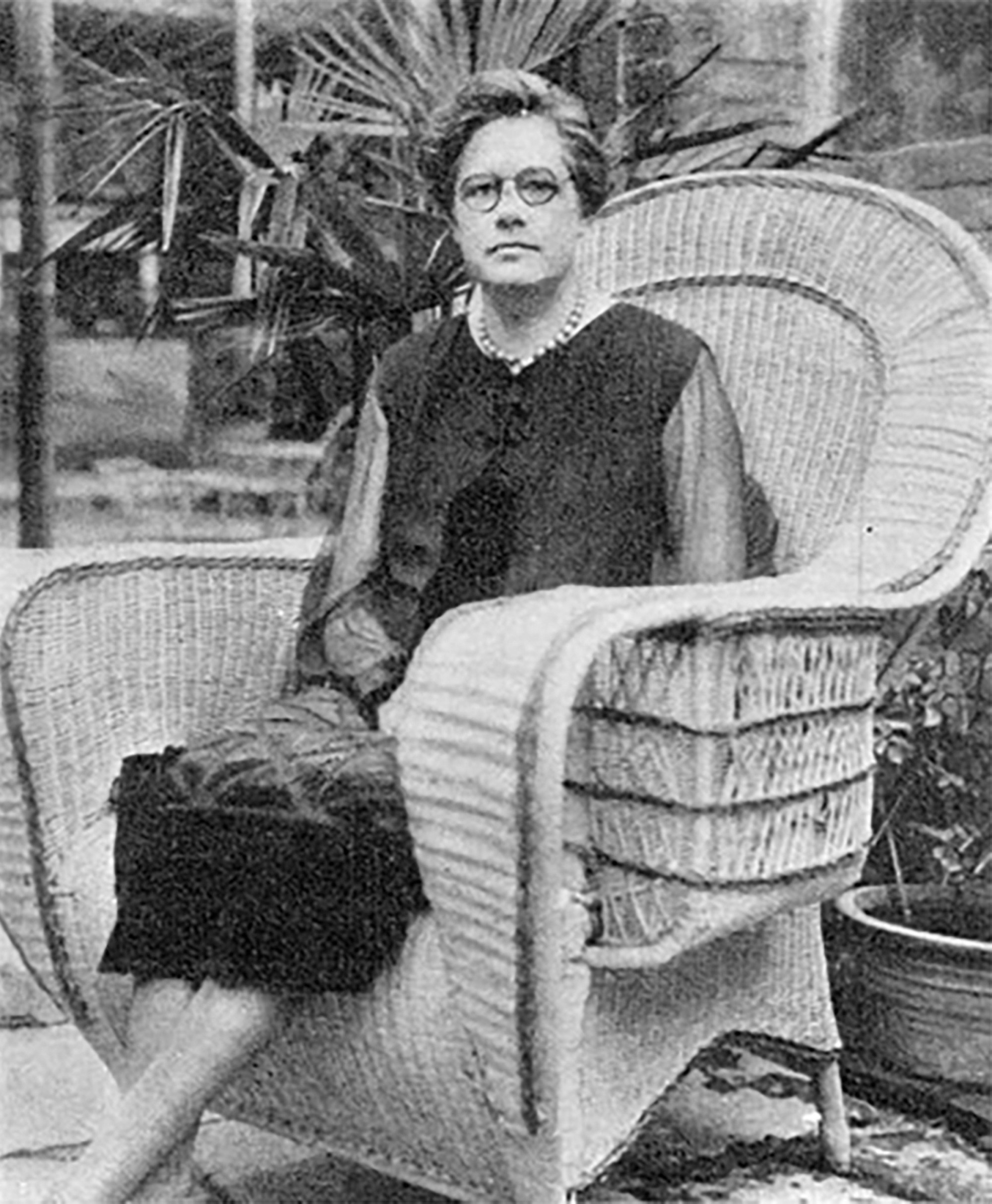

But Fette hadn’t originally come to China to set up a carpet factory. She was a chemistry graduate from Indiana, and had arrived in Beijing in 1919, working for the Methodist Mission School.

Her husband, Franklin Fette, an Iowan professor of public hygiene, had been recruited by Yenching University in Beijing, where Helen Fette eventually swapped saving souls for building a family home and caring for her two children.

Fette took a special interest in the local rug weavers and the techniques for dyeing the particularly soft Mongolian and Shanxi wool, educating herself on the history of Chinese carpets and their design, and decorating the Fette family’s Beijing home with them.

A visiting friend fell in love with one of Fette’s purchases and offered her several times what she had paid for it. She accepted and donated the profit to famine relief in nearby Hebei province. Franklin’s university wages were low and on occasion did not materialise, so Fette decided that rugs could be an additional source of income.

She began acquiring stock to sell in the US, buying low and selling high to expatriates and tourists. Soon she needed more rugs than she could source and so suggested the idea of a joint venture to a manufacturer with whom she had become friendly, Li Mengshu.

Li knew how to weave rugs, Fette knew designers and how to reach the high-end retail market. Together they formed the Fette-Li Rug Company.

Other American and European retailers were ordering rugs direct from China, but they had no input into either the designs or the quality.

The pair started with a limited range of Fette-Li rugs in Chinese patterns, and a sales office on Beijing’s busy Hatamen Street (now Chongwenmen Dajie). Fette recruited a friend, a Mrs Cuthbertson, who taught art at Tsinghua University.

They soon expanded to the potentially even larger market of Shanghai. Fette-Li sold through the upscale stores nestled in the lobbies of large hotels – The Camel’s Bell boutique in the foyer of the Grand Hôtel de Pékin, on Chang’an Jie, or Gray’s Yellow Lantern Store in the busy atrium of the Cathay Hotel, on Shanghai’s Bund. Sales were brisk.

But the duo were not entering an open market. Demand for hand-tufted, especially thick-pile Tientsin carpets, was already booming, and Beijing and Tianjin manufacturers had been selling their rugs overseas for some time.

A few other foreigners resident in China had thought to work with manufacturers in Tianjin, including Fette-Li’s biggest competitor, American Walter Nichols, though he did not produce the same wide range of designs as Fette-Li.

By the late 1920s, Tianjin alone boasted more than 300 workshops, mills and factories relying on a cottage industry of hand-spun wool from home workshops.

At the same time labour costs doubled and the US sunk into the Great Depression, dampening consumer demand. After such a promising start things began to look bleak for Fette-Li.

Herself a trained chemist, Fette developed new, modern-feeling natural dyes in pastel shades.

She felt these more subdued colour tones, beiges and creams not traditionally seen in Chinese rugs, harmonised better with emerging North American and European interior decor trends.

Fette-Li produced a range of rugs incorporating Spanish-style motifs, copies of designs from Granada and Andalusia that Fette had admired in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art (which did grant permission for the reproductions).

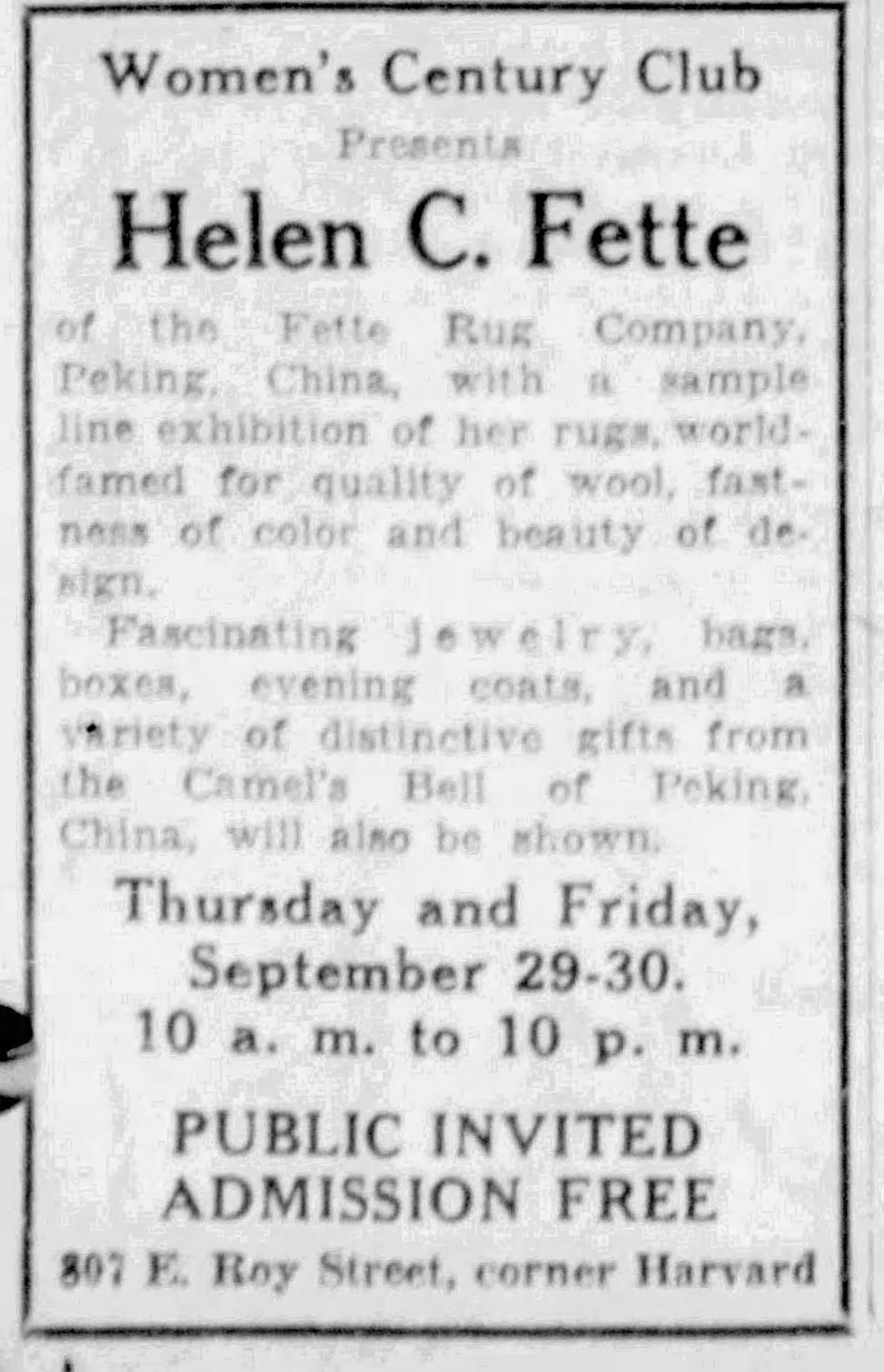

From the late 1920s, Fette travelled regularly to the US on promotional tours. She visited various women’s clubs, art galleries and private homes holding trunk sales. Her activities were widely reported in local newspapers wherever she took her roadshow.

She found several women who volunteered to be sales reps for her in various parts of the country. One of them, Alleyne Archibald, was so impressed by Fette-Li’s rugs that she opened a small and exclusive boutique inside the Miami Biltmore Hotel, in Coral Gables, Florida.

Indeed, such was the success of the rugs in the US that Fette’s sister-in-law, Beatrice Fette, began selling Fette-Li rugs from her home on Canal Boulevard in Waikiki, Hawaii, and advertising in the Honolulu Star-Bulletin that anyone who was interested was welcome to drop by anytime and see the beautiful rugs in situ – “Look for the White House with the Blue Roof”.

By the end of the decade, this former missionary-school teacher and Beijing expat mother had become quite the businesswoman. Fette regularly held trunk sales, displaying her merchandise in people’s homes and in hotels.

In her pitches Fette would introduce her rugs by evoking the endless unspoilt Mongolian grasslands that gave Fette-Li its unique feel.

She would claim to have adopted rug-making techniques, as she told Canadian newspaper The Vancouver News-Herald, “handed down from the Lama Priests of Tibet”.

As Fette’s trunk sales attracted interest, word spread. US dealers increasingly inquired about taking stock and whether more rugs could be dispatched, or additional contemporary patterns designed.

From meeting so many customers face to face, Fette had learned that her rugs needed to be resized, usually smaller, to better fit the average American living room. Fette-Li also began to receive their first custom orders from offices and hotels.

Fette returned to Beijing, money in the bank, a full order book and bursting with enthusiasm and expansion plans.

By visiting as many American rug dealers as she could, Fette gained good market intelligence from the growing number of high-end Oriental rug stores in New York, Boston and Los Angeles about how aesthetics and trends were changing.

The Chinese and Iberian motifs were falling out of favour as art deco became the most sought-after style. So back in Beijing, Fette sent for designers with whom she had been in contact, most from the Pacific northwest. These included two Tacoma natives who had links to the University of Washington’s art department in Seattle.

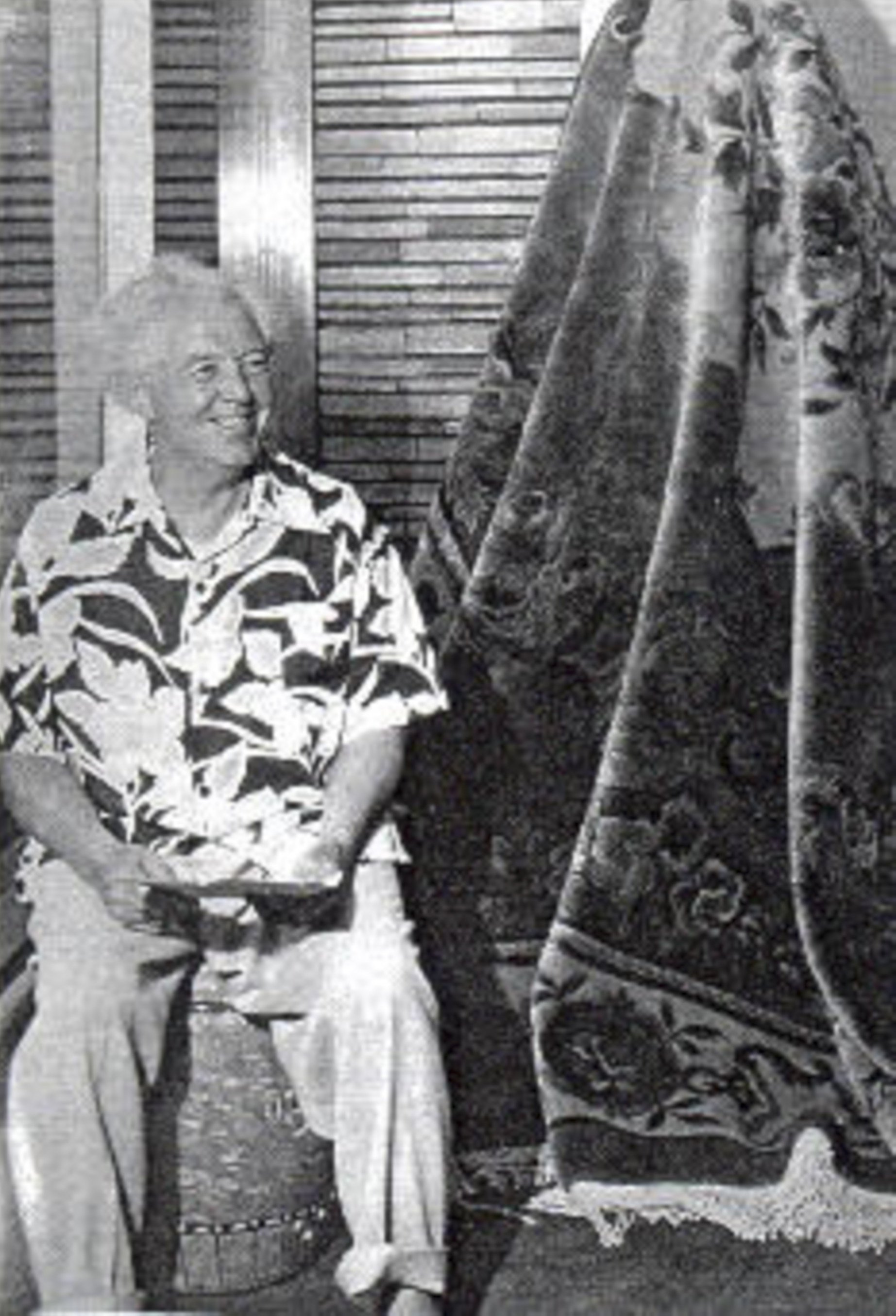

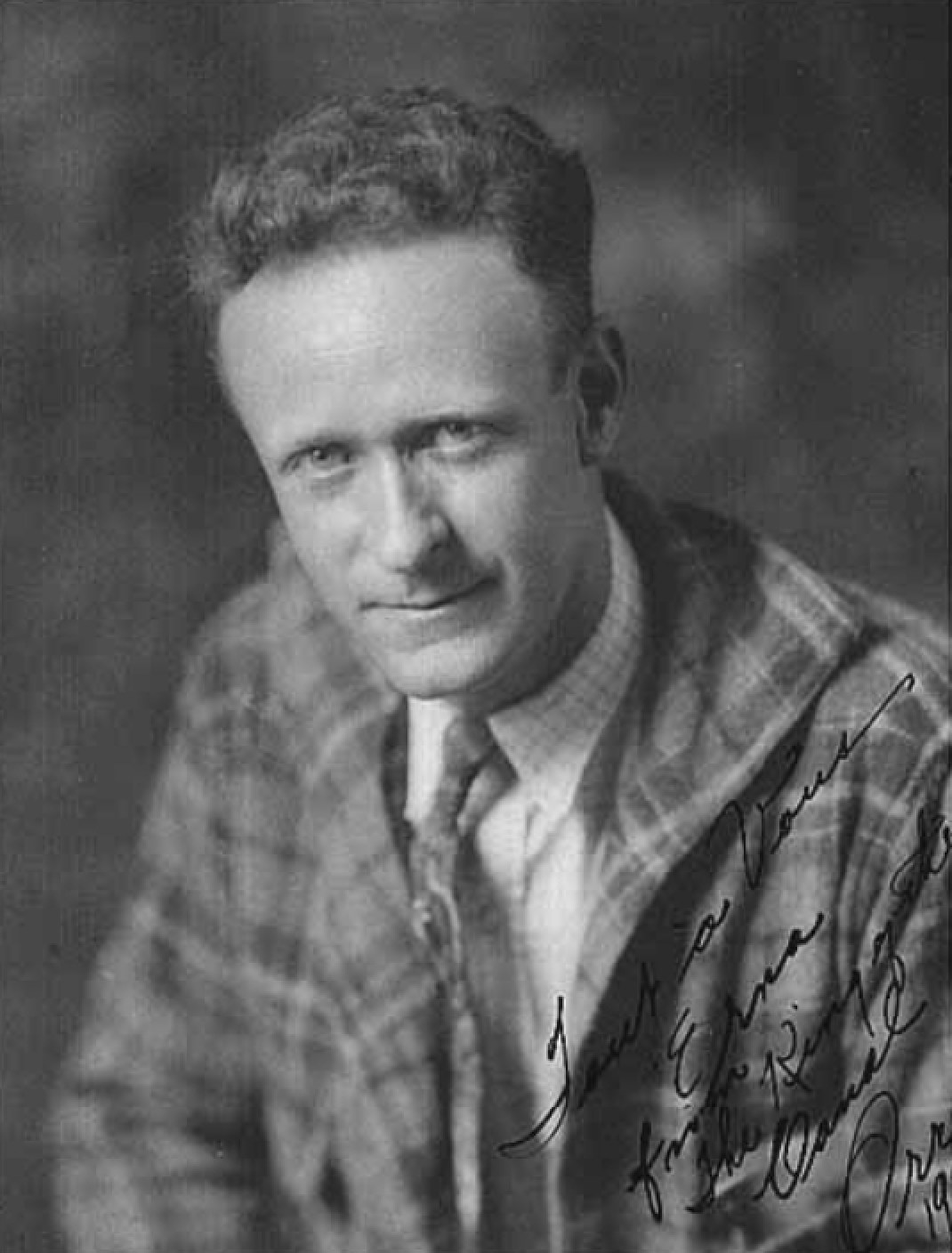

Orre Nobles was a graduate of Manhattan’s Pratt Institute, and Thomas Handforth had left the US to study at the École des Beaux-Arts, in Paris. Both men arrived in 1929 and would reside in Beijing for many years.

While starting out as rug designers for Fette-Li, they would become better known for other things – Nobles for photography and Handforth as the award-winning illustrator of the 1938 bestselling children’s book Mei Li.

Orders also began to come in from rug dealers across the US and Europe, with sales representatives appointed in London, Paris, Berlin, Rome, Scandinavia and as far afield as Latin America.

In an account of his work with Fette-Li, Nobles recalls having great success in the US with a series of rug designs based on textile hangings he had sketched in Beijing’s Buddhist temples, as well as a pictured rug featuring the Beijing skyline detailed in black silhouette against a yellow foreground.

Ever the chemist, Fette continued her experiments with dyes, wanting to diversify away from the traditional Chinese reds and blues and differentiate Fette-Li rugs as being more contemporary.

She tried a range of coloured dyes produced in Germany and the US that hadn’t been widely used by the local rug industry in northern China before. Meanwhile, by the early 1930s, with Fette returning from the US with additional orders, Li had some problems to solve.

Fette-Li desperately needed to ramp up production, both in volume and range, if it was going to meet the demand Fette was generating.

Sourcing additional wool, as well as finding the home workers to card and spin it, and the factory space to dye and weave, was a challenge. Realistically, Li estimated that it would be impossible to produce more than 25,000 feet of carpet a month.

This was a small volume by the standards of some of their competitors, but Fette-Li was selling its rugs overseas at substantially higher prices than the other Tianjin mills.

Volume was important, but quality of design and manufacture was what had set Fette-Li apart from the pack.

By the early 1930s, the company employed about 2,000 workers – 1,300 or so being home-working carders and spinners. Fette told the readers of the Miami Herald, “Creating a large rug can mean four weavers working full time for several months.”

As fast as the Fette-Li mills could produce rugs they were snapped up. Fette had to inform her reps, retail stockists and customers that there was a six-month waiting list. But she insisted on high standards of production even if this prevented any increase in volume.

Fortunately we know a lot about how Fette-Li rugs were produced. Nobles hand-typed a self-published pamphlet explaining the process, “How a Fette Rug is Made”, in 1931.

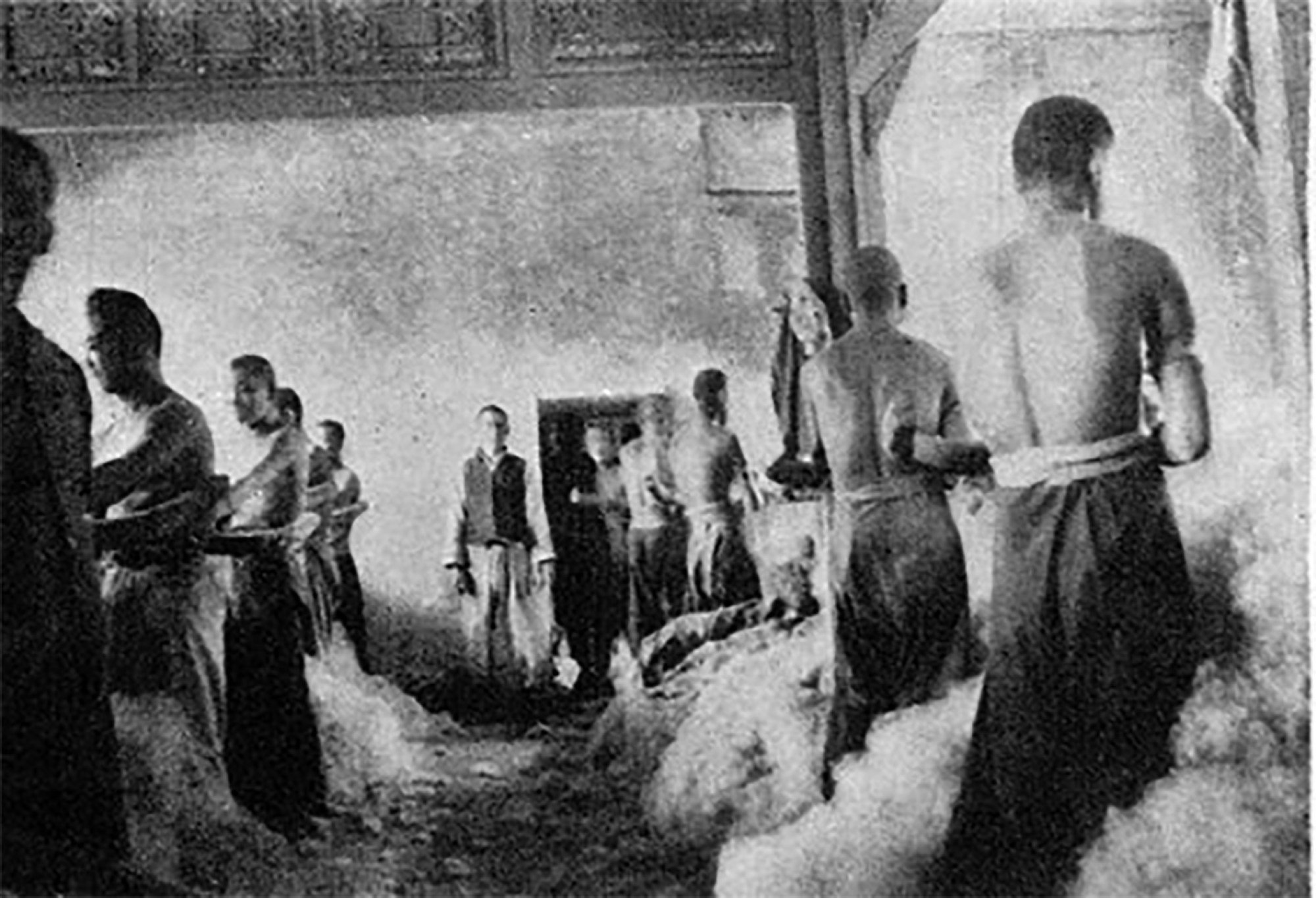

He described how fleece from Mongolia and Shanxi, the best providers of quality long-fibre wool, was delivered in massive hessian sacks to the Fette-Li mills in Tianjin. This itself could be a hazardous journey of more than 1,600km (1000 miles).

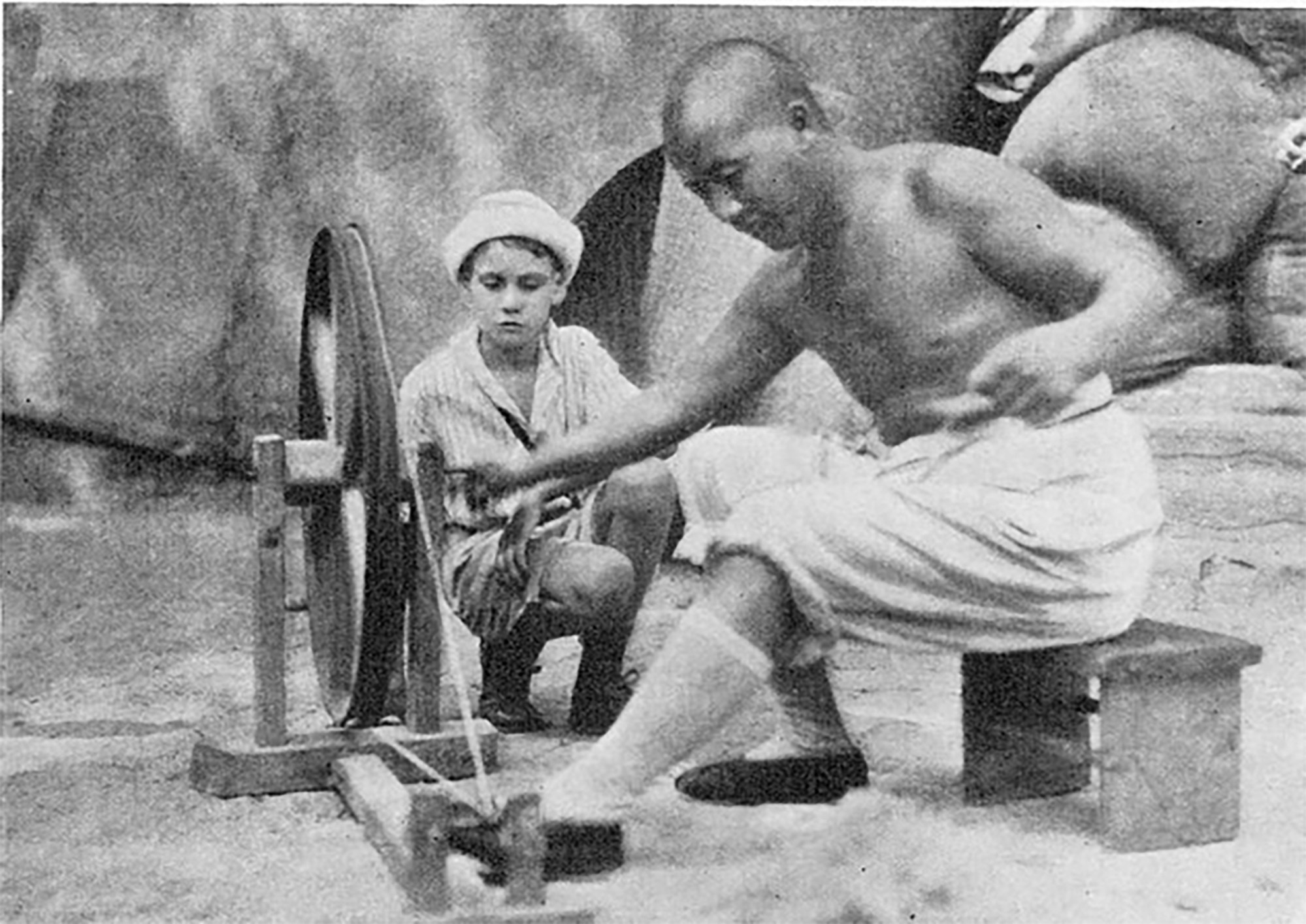

It had to be cleaned in the factory then sent out to be carded and spun in hundreds of home workshops on foot- or hand-propelled spinning wheels.

As part of the firm’s expansion, Li had constructed a separate dyeing plant in Tianjin with adequate ventilation and large exterior drying yards.

Fette-Li rugs were typically nine by 12 feet (2.7 by 3.7 metres) or 11 by 14 feet for a living room and four by seven feet for a bedroom. Seventeen by 18 feet was the largest size the firm could produce, usually custom orders for offices or hotels.

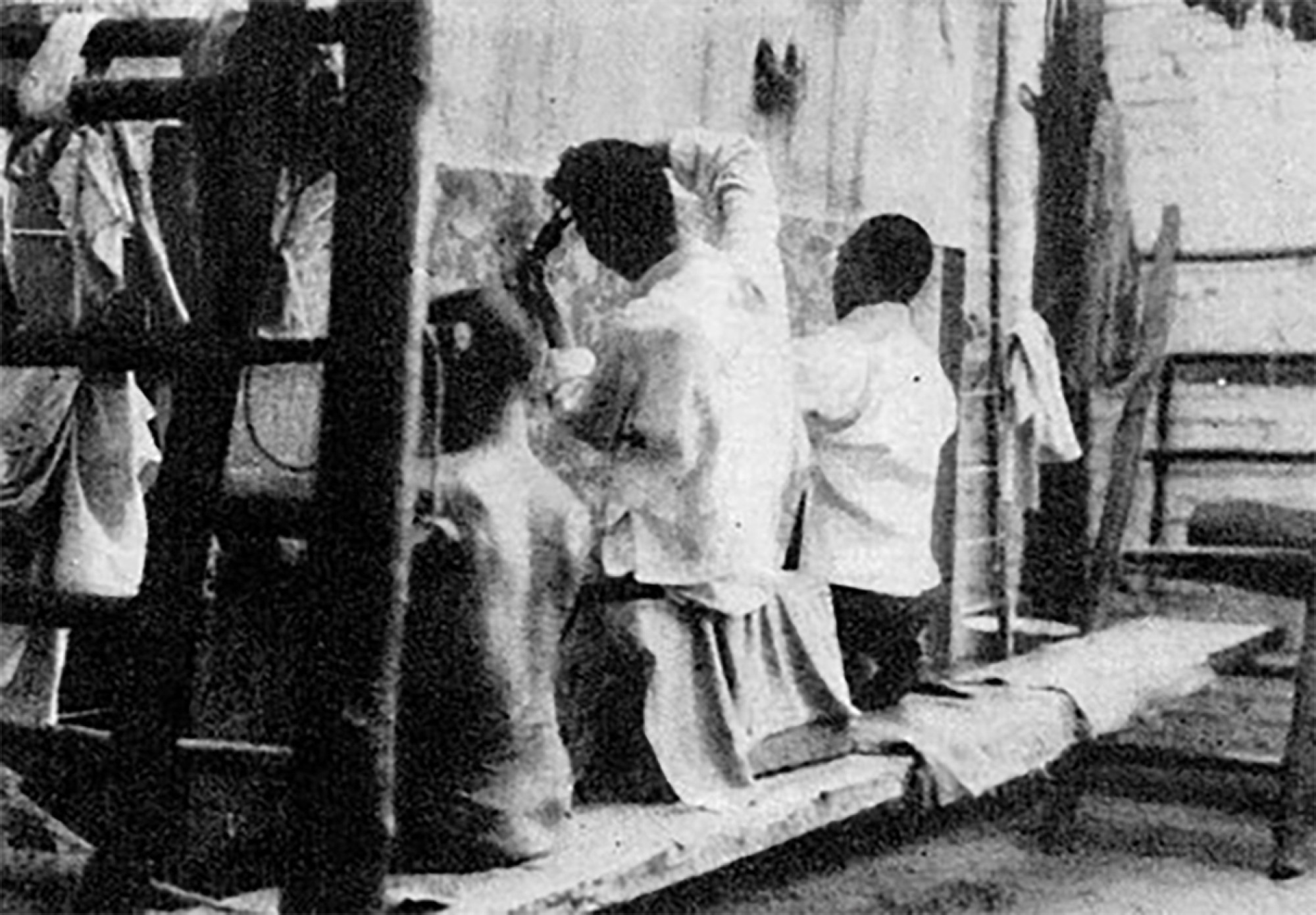

Then the master artist, who could be Nobles, Handforth or one of the Chinese designers employed to produce the still popular traditional motifs, would draw their pattern on the background.

Fette-Li employed about 2,000 male weavers at its mills – the job was exclusively a male occupation.

The company became the first Tianjin rug company to break the convention of unpaid apprenticeships and provide young trainees a wage (though weaving remained an all-male preserve).

The weavers would work from the reverse of the rug to detail the pattern by beginning the tedious process of tying the various wool yarns into the background. Thousands of individual figure-of-eight knots eventually created the distinctive pattern.

According to Nobles, at any given time the weavers would be working on 200 rugs positioned alongside each other on looms.

Once completed, a rug would be inspected by the head weaver, the master artist and the shipping office’s head checker before being boxed and passed to the dispatch clerks for transport overseas.

But there was a dark side to the north China rug industry that concerned Helen and Franklin Fette, with high tuberculosis rates and terrible eye diseases common.

Throughout the production process, trachoma, an eye disease caused by bacterial infection, often transmitted by flies, was a constant concern. It was painful and invariably led to blindness.

The infection is spread by the direct or indirect transfer of eye and nose discharges from infected people, particularly children, and is especially prevalent in weaving industries.

Many children lived in the homes where the spinning took place, many also worked in their family’s spinning business.

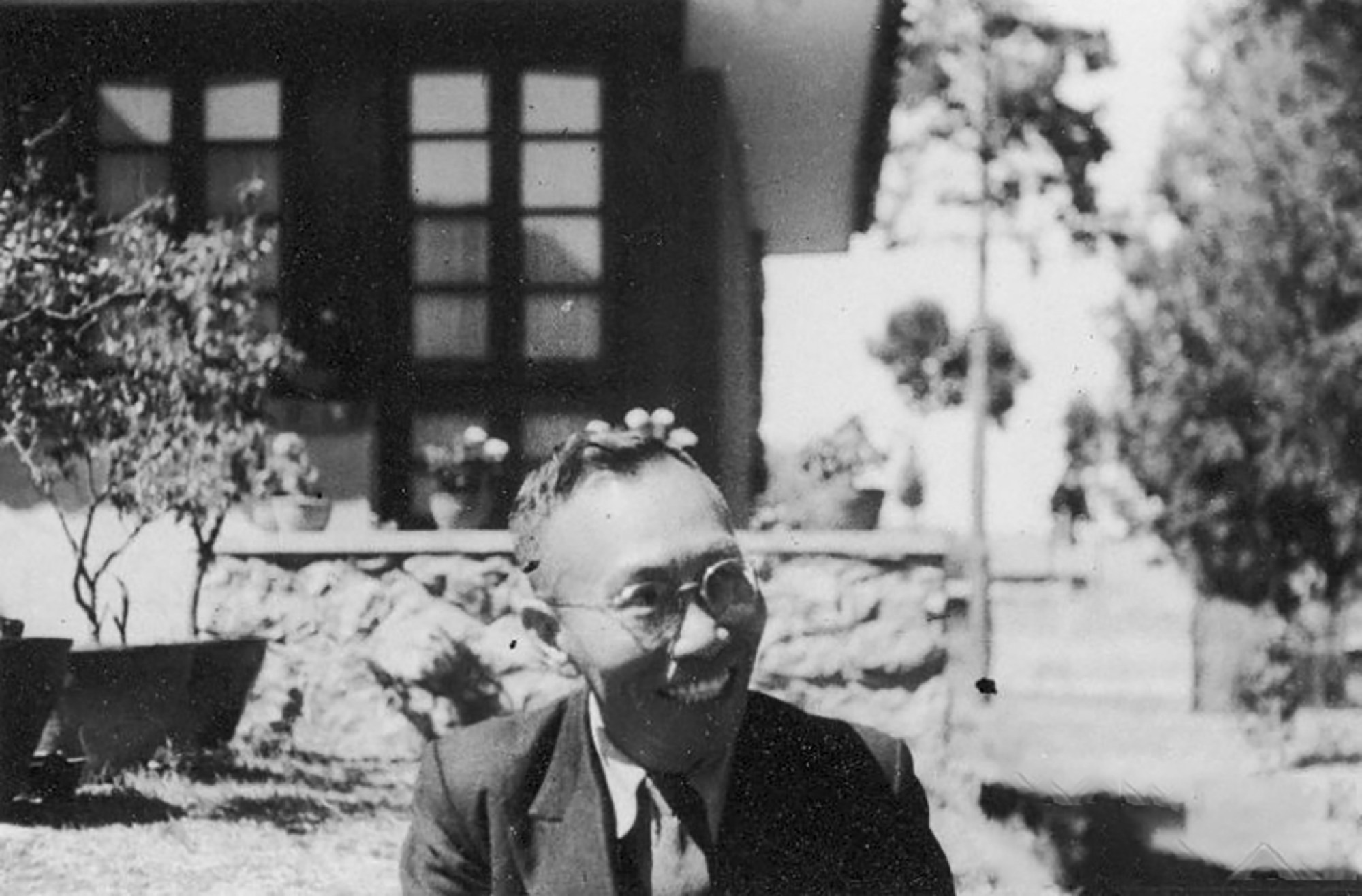

As a professor of public hygiene, Franklin Fette was keen to set a high standard of worker healthcare within the Fette-Li Rug Company. He introduced a regimen of regular hand-washing and nose-blowing, banned spitting and issued warnings about rubbing infected eyes to avoid exacerbating the condition.

He insisted the weaving rooms be lit and ventilated, as well as heated in winter. Li opened a factory canteen – meat twice a week and fresh vegetables every day. However, conditions were harder to improve among the home workshop spinners.

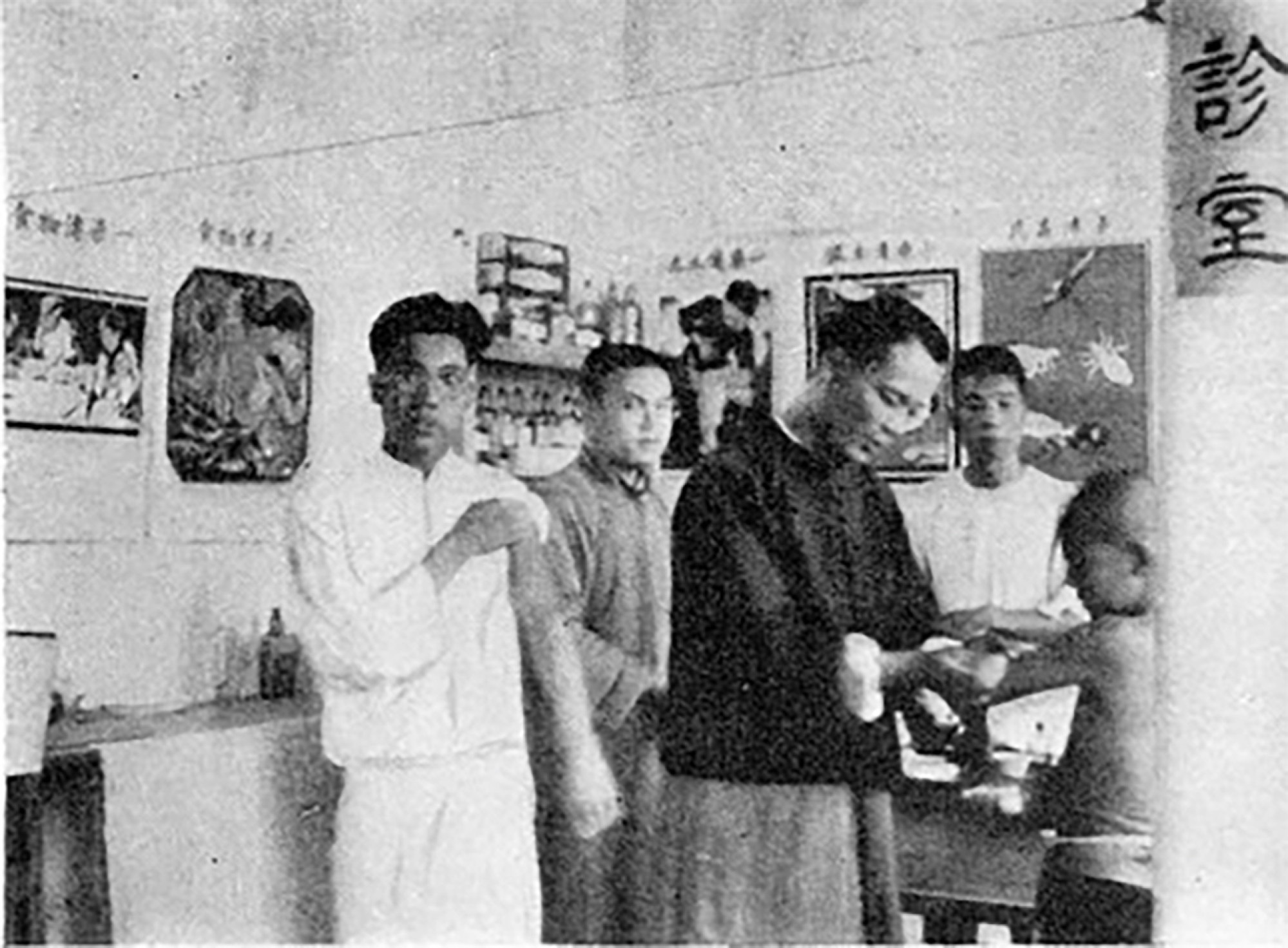

Fette had met Chinese microbiologist Dr Tang Feifan at Peking Union Medical College. In the 1930s, Tang was following the leads of Japanese scientists to try and isolate the bacteria that caused trachoma.

While this did not cure the problem – war and revolution intervened and Tang did not manage to identify the specific bacteria that causes trachoma until the mid-1950s – the vaccines combined with rigorously enforced hygiene protocols did reduce the incidences of trachoma among the washers, spinners, dyers and weavers working for Fette-Li.

At the time, the company had far and away the most advanced trachoma-prevention programme in the northern Chinese carpet-making industry.

Throughout the 1930s, Fette-Li maintained production of at least 25,000 feet of carpet a month, or several thousand individual rugs.

These were shipped worldwide direct to people’s homes, department stores, specialist rug dealers and custom clients in Manila, Tokyo, New York, London and dozens of other cities.

Fette-Li became a recognised brand, featuring regularly in newspaper adverts and auction-house catalogues. Orders continued to pour in.

But, having survived the warlord and bandit hijackings of supplies, soaring wool costs in Mongolia, and the Great Depression in the US, it was to be World War II and the Japanese attacks on Beijing and Tianjin that destroyed Fette-Li.

By the summer of 1937, both cities were occupied by the Japanese. Helen Fette and Li tried their best to keep the business going but wool supplies were disrupted, mail services suspended, shipping routes problematic and banks closed as inflation spiralled.

The Fettes and their now-grown children managed to leave China before the Japanese began interning Allied nationals after 1942. They returned to the US in the summer of 1941 and settled in Palo Alto, California. They never restarted the business.

Helen Fette died in 1956, aged 74. Franklin Fette moved to St Louis, Missouri, and died there in 1959, aged 81.

Their son, Franklin Russell Fette, continued to lobby the Chinese authorities into the 1970s requesting compensation for the family’s rug mills, which though closed since the war had been confiscated in the 1950s.

In 1979, he was one of 677 expropriated American claimants still pursuing compensation. He was seeking the sum of US$64,092, which would be worth US$230,000 (HK$1.8 million) today.

It is not clear whether there was a settlement, but if there had been it would have been a few cents on the dollar at best.

The new authorities paid small amounts to settle and make the problem of claimants go away, but only a fraction of real values was paid out.

Fette and Li are largely forgotten today but many people attracted by art deco designs or colourful traditional Chinese styles find themselves drawn to Fette-Li rugs when they appear in specialist dealer or auction catalogues without realising their provenance.

Helen Fette and Li Mengshu revolutionised the northern Chinese rug industry – in terms of design, manufacture, sales reach and working conditions.

Most importantly, perhaps, a Fette-Li rug is still a beautiful piece to own. These rugs can command relatively high prices given their vintage (the earliest are not yet quite a century old). A hand-knotted, late-1920s, art deco rug can easily fetch HK$100,000.

An English rug collector who specialises in traditional Chinese rugs, as well as Turkish kilims, but who also appreciates more contemporary carpets, told me that when they do come up for auction he always bids.

Recently he attended an auction in southern England and bid for a late-1920s Fette-Li living room rug featuring an art deco blue-and-gold pattern surround, with a blue dragon motif in the centre. The dealer said he admired the vibrancy of the colours after nearly 100 years.

Having not been chemically lustre washed (a bleach-heavy chemical wash used by large manufacturers to give rugs a sheen), Fette-Li pieces generally age well if they have been cared for. Their colour vibrancy is natural, thanks to Fette’s dyes, and not chemically manipulated.

Additionally, the English dealer noted that, despite their age, Fette-Li rugs retain their tight weave. There was no shortage of bidders for the rug.

My dealer friend bid a decent amount knowing that he would be able to sell it on for a good mark-up. And he won. He immediately got on the phone to a collector in Beijing who had been looking for just such a rug.

There was no hesitation, a price was agreed, money transferred, a courier company called and a genuine Fette-Li rug was heading for the airport, on its way home once again.