- Characters the British author met in Hong Kong made it into one of the ex-spy’s Cold War novels, and so did an error that taught him a valuable lesson

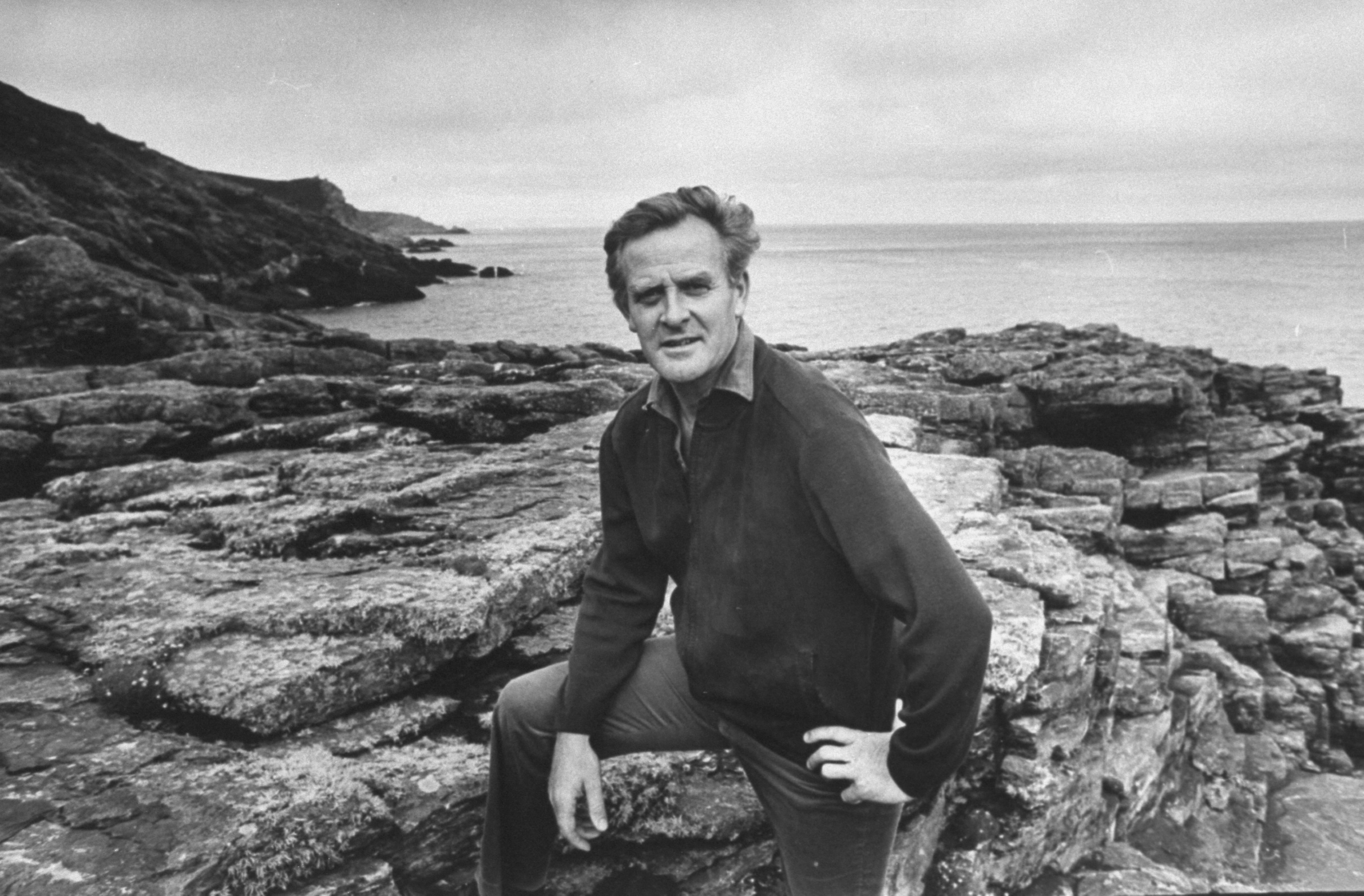

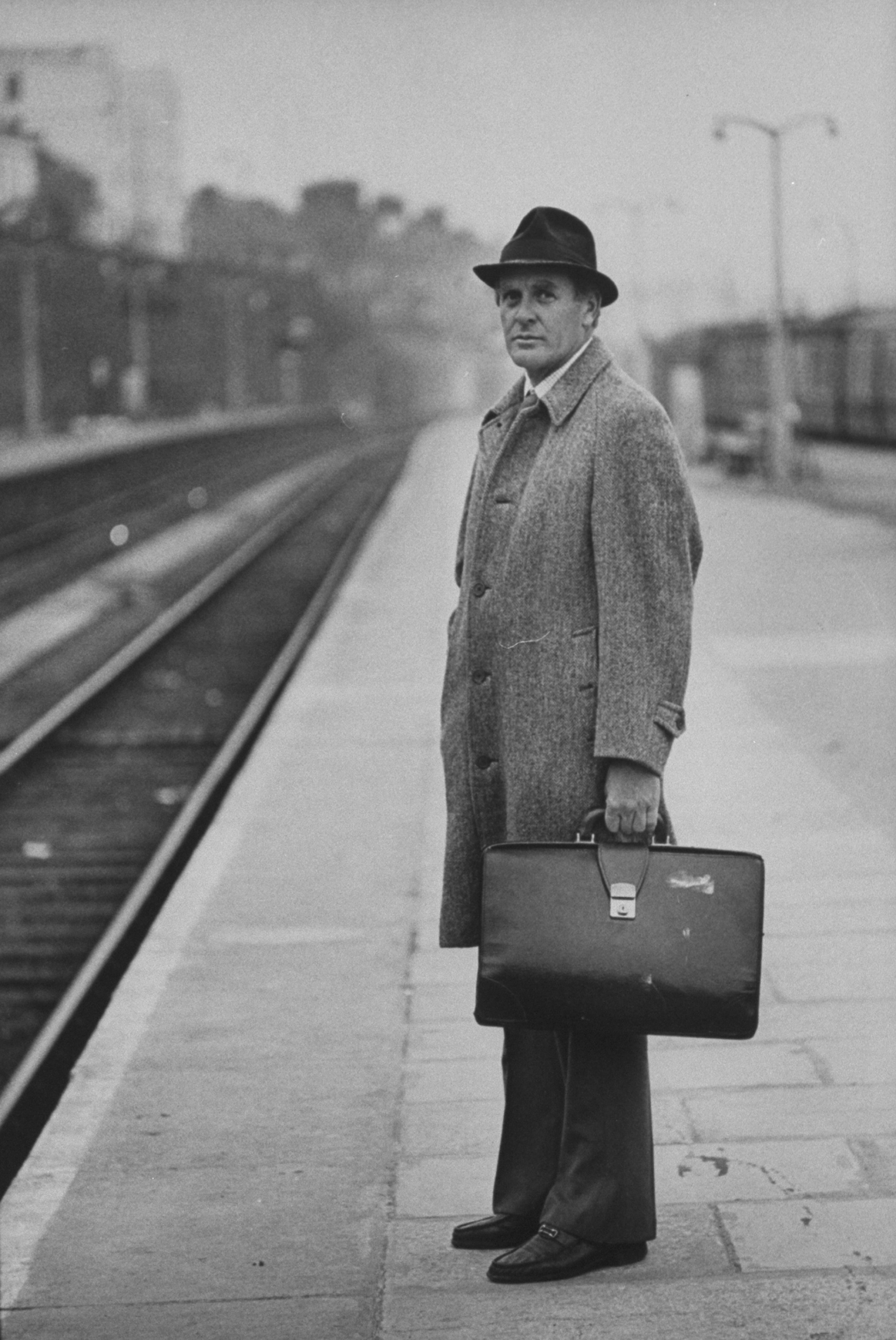

After half a dozen years working in British intelligence, David Cornwell, better known to the world as John le Carré, became a bestselling writer with his third novel, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963).

It was just as well his new career was taking off because le Carré’s days as a spy were over, thanks to Kim Philby’s defection blowing his cover to the KGB.

By the 1970s, le Carré was making a decent living from his books, and he decided he wanted to move from Europe and travel Asia to research characters, and to tell the story of the Cold War in a hot climate.

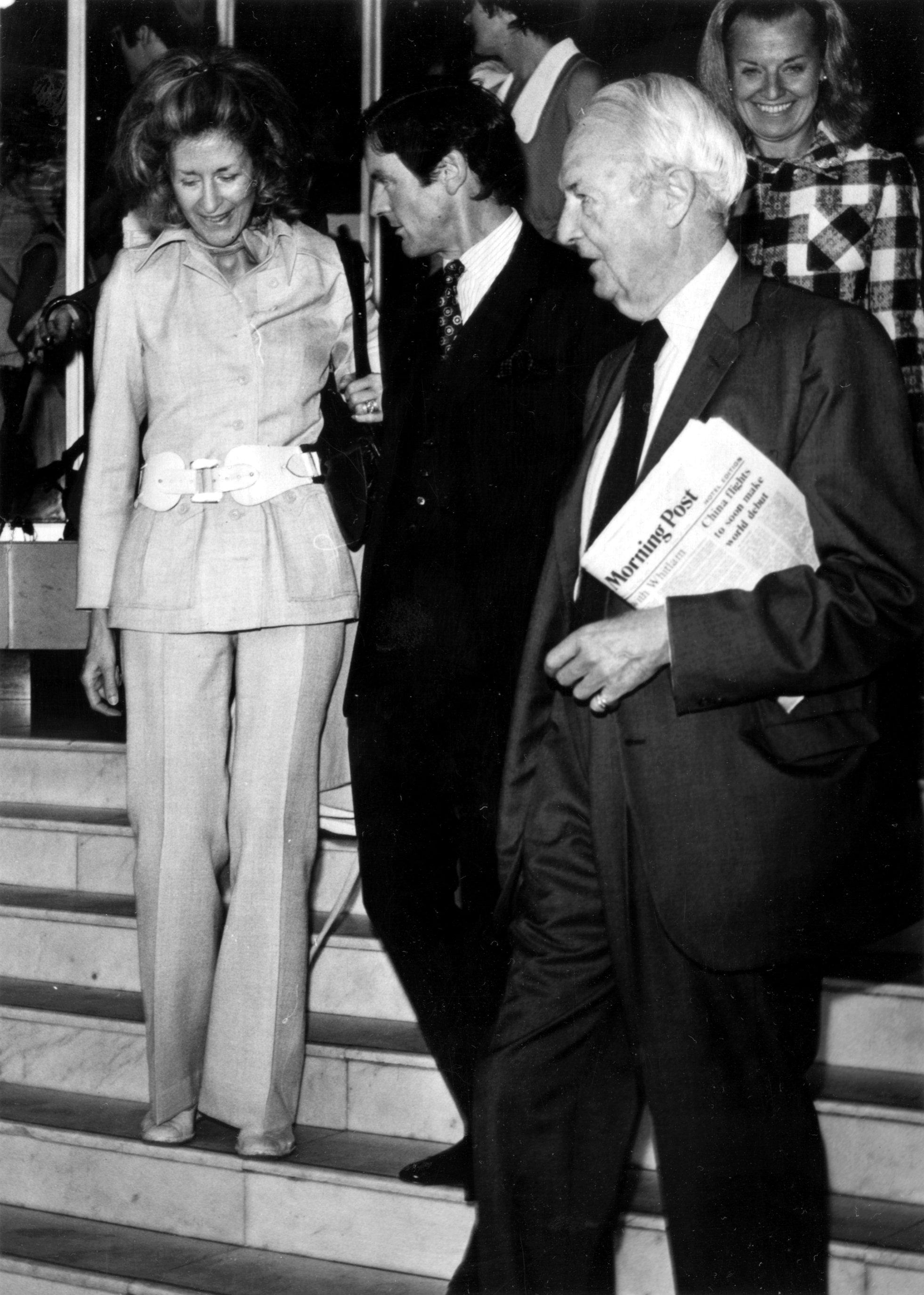

Adam Sisman, le Carré’s major biographer, says the author “wanted to get his knees brown” in a mocking reference to the days when British officials wore shorts, and so with a vague idea for a new novel to be called The Honourable Schoolboy, in February 1974 le Carré boarded a plane from London to Hong Kong.

The plan was to have travelled through northeast Thailand, Laos and Cambodia, using Hong Kong as his base on both occasions.

Before his first visit, le Carré had turned in the final proofs of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, the novel that would become a global sensation, leaving readers addicted to the battle of wits between the unobtrusive and unglamorous George Smiley and Karla, Moscow’s top spy master.

Tinker Tailor would effectively reinvent the spy novel from entertaining thriller to intellectual puzzle, but in one, somewhat throwaway scene, there was a description of a Star Ferry ride between Kowloon and Wan Chai.

He had, as he claimed in his 2016 memoir, The Pigeon Tunnel, “to his everlasting shame” written the passage at his home on the Cornish coast, in England, from an outdated guidebook.

He immediately scribbled out a new passage, phoned his agent imploring him to get the printers to hold the presses, and faxed it to London as he headed off to Bangkok for more research. He made it just in time.

In Tinker Tailor, suspected double agent Ricki Tarr describes his encounter with Irina, the wife of a Soviet trade delegate in Hong Kong, who tells him the identity of a KGB “mole” in Smiley’s office.

A rendezvous is arranged with Tufty Thesinger, MI6’s permanent agent in Hong Kong, at the Golden Gate Hotel on Austin Road in Kowloon (sadly demolished in 1979).

The Soviets indulge rather bourgeois tendencies in the Cat’s Cradle club Kowloon-side before “cutting back through the tunnel to Wan Chai” and a sailor bar called Angelika’s.

And in The Honourable Schoolboy he made sure to include the tunnel as a character escapes by deserting his car and running through stationary traffic to the tunnel’s exit.

Before leaving Europe le Carré had sought out contacts, guides and letters of introduction to those who knew the region best to facilitate his deep dive.

His reading list (courtesy of London’s famous Heywood Hill bookshop and its manager, John Saumarez Smith, known to le Carré as “Samurai Smith”) included The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia (1972), by the specialist in CIA covert operations Alfred W. McCoy, and perhaps inevitably, Graham Greene’s 1955 novel of the simmering tensions in Vietnam, The Quiet American.

He couldn’t deny its brilliance and although le Carré and Greene had fallen out in the past over, as le Carré saw it, Greene’s apologism for Philby’s betrayals, he did write to him that the novel, “seems as fresh to me now as it did nineteen years ago, and it is surely still the only novel, even now, which does justice to its theme”.

Le Carré’s initial introductions to the region’s rather shady espionage characters were via Sir John Margetson, a former spy turned diplomat, an Asia hand who had served in the British embassy in Saigon in the 1960s.

This had been a tricky posting as then prime minister, Harold Wilson, had been determined to avoid committing British troops to the Vietnam war.

Through Margetson le Carré was introduced to a host of foreign correspondents in the region, including Laurence Stern who, in the 1970s, was The Washington Post’s first so-called Dulles Airport correspondent, available day or night to fly anywhere in the world for the big story.

That job had taken him to Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, where he had observed the collapse of the American effort and retreated regularly to the safety of Hong Kong for R&R at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club (FCC) bar.

Stern was a genuine reporter. Le Carré, of course, was more interested in those with double, and often dubious, lives.

So Margetson also introduced le Carré to Peter Simms, who is now perhaps less well remembered than other le Carré associates of the time but was, as le Carré himself remembered in The Pigeon Tunnel: “a veteran British foreign correspondent and […] as is now generally known, though at the time I knew it no better than anyone else, a veteran British secret agent”.

Simms had also seen service with the Bombay Sappers – a regiment of the Corps of Engineers of the Indian Army – in World War II and was a scholar of Sanskrit. He fell in love with a princess of Shan State – in what was then Burma – called Sanda, converted to Buddhism and eventually married her in Bangkok.

He taught in Rangoon, wrote for Time magazine in Singapore, advised the Sultan of Oman, and worked for the Hong Kong Police’s Special Branch division, all while, most probably muses le Carré, being “on Her Majesty’s Secret Service, at least part-time, and […] if he wasn’t already working for British Intelligence, then it was sheer carelessness on their part”.

After meeting at Raffles hotel in Singapore, again in Hong Kong, and once more in Bangkok, le Carré asked Simms to accompany him to the “stickier corners” of Laos and Cambodia.

“You jolly well bet I would, the old cash flow could do with a spot of topping up, no question,” Simms replied – far from the only “occasional” remark on MI6’s parsimony. Le Carré thought of Simms as not dissimilar to Greene’s cynical British hack Thomas Fowler in The Quiet American.

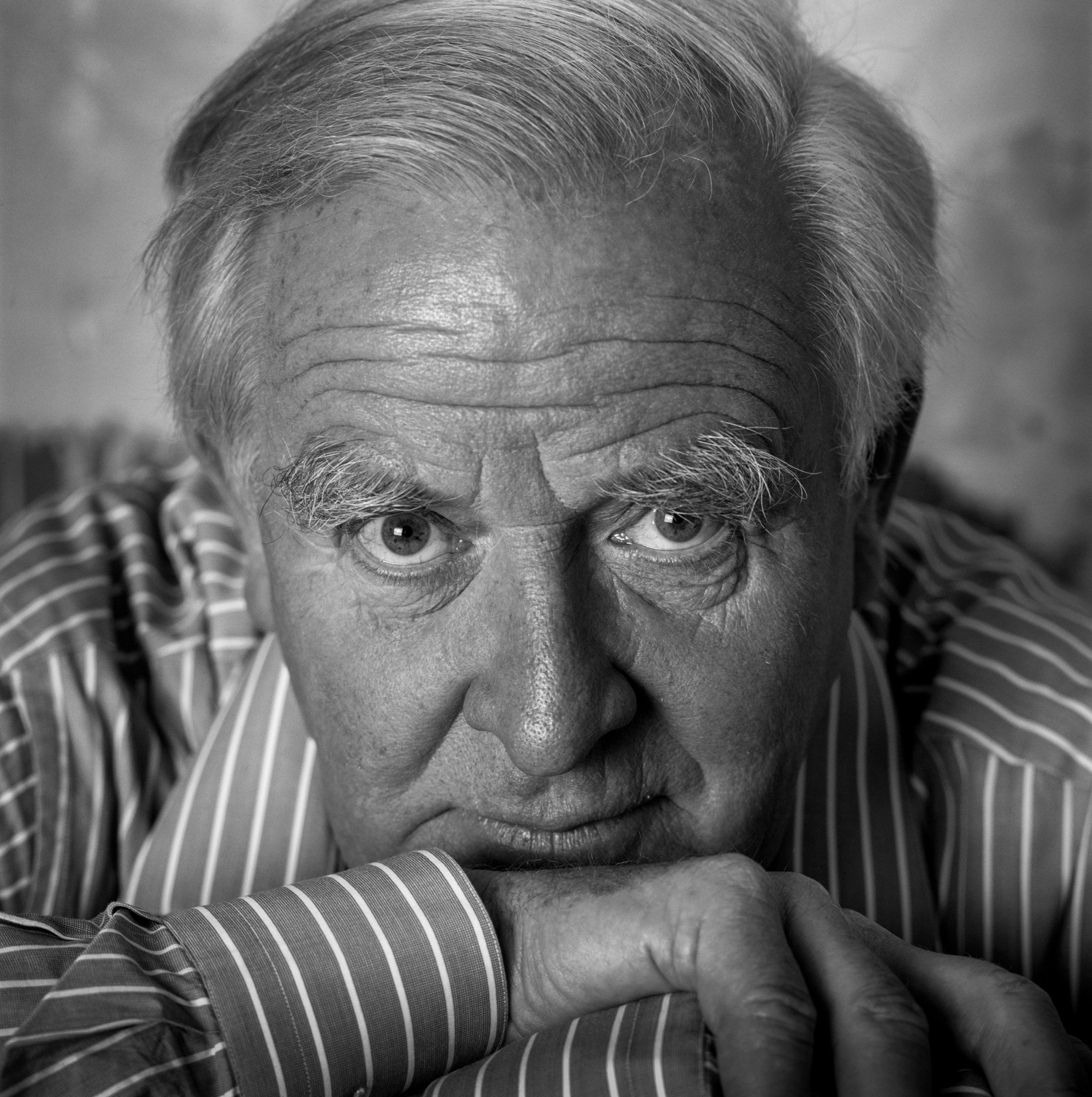

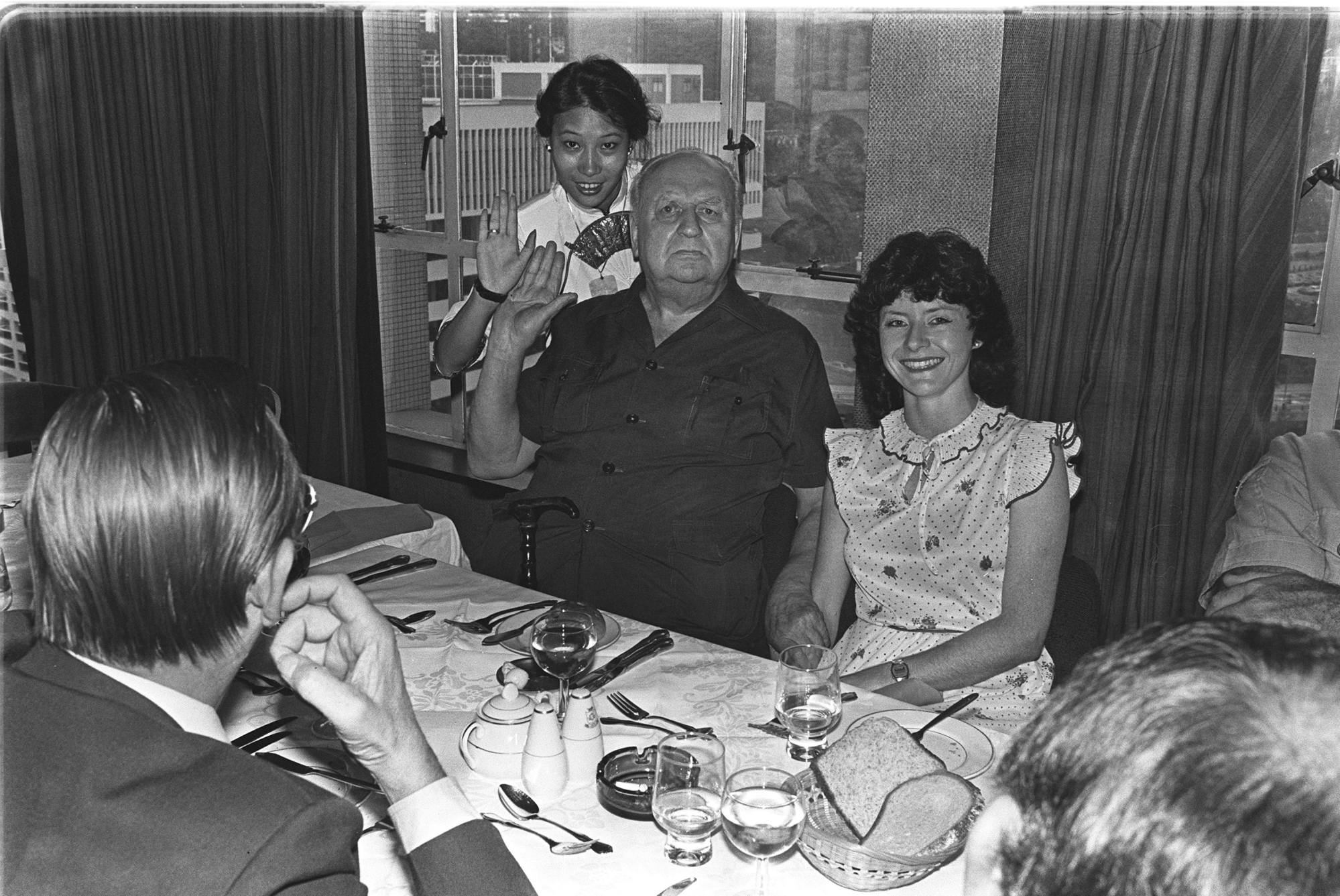

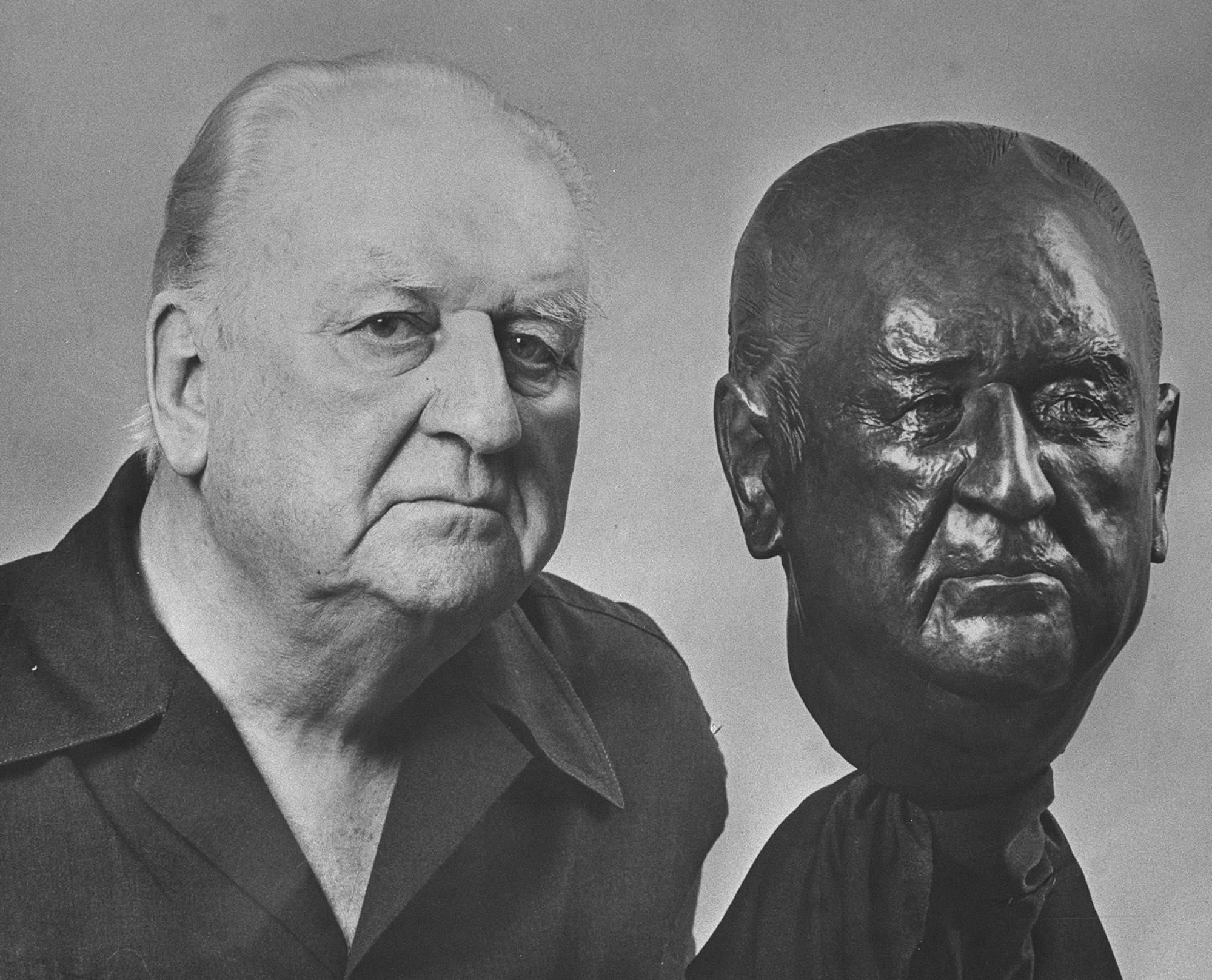

It was likely Simms who introduced le Carré to Dick “Cardinal” Hughes (he tended to quote from the Bible), a larger-than-life Australian journalist known for his bonhomie, a possible “UA” (unofficial assistant) for MI6, a solid fixture at the FCC bar and author of one of the more insightful foreign correspondent memoirs of Asia, Foreign Devil (1972).

He was immediately of interest to le Carré. Irreverent, with a twinkle in the eye that seemed to presage the telling of secrets, he was a raconteur’s raconteur with a knack for being in the right place at the right time – Tokyo and Shanghai in 1940, North Africa during World War II, and both the Korean and Vietnam wars.

He was married to the daughter of a Nationalist Chinese general. Irresistibly to le Carré, the former intelligence man and spy novelist, Hughes had been the first foreign reporter to interview the British traitors Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean after they defected to Moscow.

As the Sunday Times correspondent Hughes held court at the FCC, then in the now demolished Sutherland House on Chater Road.

The FCC’s lavatories were on the 14th floor and commanded a splendid view of Victoria Harbour – the impressively scenic urinal features in The Honourable Schoolboy while a photograph of that view remains in the men’s loo at the FCC’s current Lower Albert Road location.

Both Simms and Hughes made it into The Honourable Schoolboy. Simms, by le Carré’s description in The Pigeon Tunnel, was “six foot three with sandy hair and a schoolboy grin, and a habit of barking ‘supah!’ when he fervently shook your hand in greeting”.

The history (and debauchery) of Hong Kong’s Foreign Correspondents’ Club

It was a game le Carré loved ever afterwards, perhaps due to the fact that the best players are those with an innate ability to deceive and to detect an opponent’s deception.

It was Simms, however, who made it into The Honourable Schoolboy. His natural gregariousness and somewhat peripatetic career made Simms the perfect model for Jerry Westerby, a reporter and retired (a.k.a. washed up) agent brought back into the field by Smiley and dispatched to Hong Kong.

Westerby is pure Simms, though denied the long and happy marriage Simms enjoyed to his Burmese princess.

Memorable as Westerby is for many readers, it’s the character of William “Old” Craw, the ageing journalist working for MI6 and Smiley’s “Circus”, that most remember.

In his biography of le Carré, Sisman recalls the author saying of Hughes, “Some people, once met, simply elbow their way into a novel.” And le Carré admitted Old Craw was Hughes incarnate in the introduction to The Honourable Schoolboy – “his outward character and mannerisms I have shamelessly exaggerated for the part of Old Craw”.

We meet him propping up the bar of the FCC, its most veteran member, as a typhoon heads towards the city: “in Shanghai, where his career had started, he had been teaboy and city editor to the only English-speaking journal in the port […]

“Craw gave them all a sense of history in this rootless place […] under the willed roughness of his manner lay a love of the East which seemed sometimes to string him tighter than he could stand, so that there were months when he would disappear from sight altogether, and like a sulky elephant go off on his private paths until he was once more fit to live with.”

He and le Carré became firm friends, drinking partners and Liar’s Dice aficionados at the FCC.

In April 1975, le Carré returned to Hong Kong, and to The Mandarin hotel. On his first visit he had made friends with the legendary general manager of The Mandarin, Australian Peter Stafford.

Indeed, le Carré was deeply in Stafford’s debt – the previous year the GM had personally stayed up late into the night assisting the panicking author in trying to reach his London agent to delete the Star Ferry sequence, showing him how to use the newfangled technology of the fax machine.

Stafford greeted him in the lobby and checked le Carré into Room 1714, where he slept for 14 hours. Stafford was to become a crucial fixer for le Carré – introducing him to the big cheeses at the Hong Kong Jockey Club, who kindly gave him the run of Happy Valley racecourse, a key location in The Honourable Schoolboy.

Le Carré preferred the evening races and late-night drinks to escape the brutal early heat and humidity to which he was totally unused.

Having hit it off on the author’s first trip, Stafford and le Carré’s friendship grew on the second.

Brisbane-born Stafford had joined the Royal Australian Air Force as a trainee navigator in 1943 but just missed active service in the war.

After Victory in Europe Day he took part in operations rescuing prisoners of war stranded in Germany, and was professionalism personified in his hotel career – in the ’50s he managed the reception desk at Claridge’s, in London, the Palais d’Orsay, in Paris, the Baur au Lac, in Zurich, and then back to London as assistant manager at The Savoy.

If it were, then this was in large part due to Stafford’s perfectionism and the loyalty of his 1,200 staff – he hired a junk every Saturday afternoon for six weeks after he first arrived in the colony and invited all the staff, with their families, to join him for a picnic.

They introduced le Carré to a “Chinese millionaire” who undoubtedly became part of the character sketch for Hong Kong tycoon Drake Ko in The Honourable Schoolboy.

The evening went on until the early hours and le Carré ended up sleeping on a daybed at the Browns’ place. Eventually the scene works its way into The Honourable Schoolboy as the mottled, curmudgeonly Old Craw, needing a place to retreat, finds solace on a daybed at the Pink House.

Le Carré also, again perhaps through Stafford’s introduction, dined with the Kinloch family, long involved with the trading firm of Butterfield & Swire in both the colony and up in Shanghai.

Le Carré’s final moments in Hong Kong, before departing once more for Southeast Asia with Simms, were spent watching what he termed in a letter to Margetson, “the ‘Swatow Fleet’ [Shantou] rounding some boring small island where a great final scene plays, on their way to Canton”. And this is indeed the finale of The Honourable Schoolboy.

Ko, the tycoon linked to the British colonial establishment and a secret KGB operative – one of le Carré’s most vividly drawn villains – is lured back to Hong Kong and his fate. Jerry Westerby watches Ko’s approach in a fleet of junks sailing from Shantou …

“The forward junks were out of sight. Only the tailenders remained. From far away Jerry fancied he heard the uneven rumble of an engine, but he knew his mind was all over the place and it could have been the tumble of the waves.

“The moon passed behind the peak and the shadow of the mountain fell like a black knifepoint on the sea leaving the fields silver.”

Having been discombobulated by the newly completed Cross-Harbour Tunnel in 1974, le Carré maintained in his memoirs that he never again wrote a book without researching the setting properly.

After his trips to Asia, he became an inveterate traveller – Israel/Palestine, Central Asia, Latin America, Africa, Europe, even spending time in the sleepy old English town of Aldeburgh on the Suffolk coast, although, for one reason or another, he never wrote about Southeast Asia or Hong Kong again.

Other subjects, other places, other novels, other wars, absorbed him.

But, among an impressive pantheon of writing, The Honourable Schoolboy, eventually published in 1977, stands as perhaps his magnum opus, at least for those readers with Asian connections, and he most certainly learned his lesson from the harbour tunnel incident, and got the small stuff right.