- Little is known of the cruel treatment of Chinese people in Canada in the early 20th century, but a Vancouver museum is bringing their untold stories to light

Richard Wong’s eyes well up when he talks about his paternal grandmother, Soak May Kwan Wong. When she was by herself, she would look forlornly up at the sky and wonder when she would see her husband, Kam Sun Wong, again.

In 1909, he returned to China to marry Kwan, two years before the Qing dynasty ended.

Five years later, Kam Sun Wong returned to British Columbia, this time to become a cook, his grandson Richard guesses, because in 1918 he opened his own restaurant, West End Chop Suey House, in Prince Rupert.

“He was ‘locked up’,” says Wong. Not in a camp or the like, but “he was isolated”, unable to return to China to see his wife and family, and he stayed in the Canadian province until his death, in around 1961. His wife died two years later in China.

The extended separation of Wong’s grandparents was not uncommon during that time, a little known but dark period of Canadian history.

During the 24 years until the Exclusion Act was repealed, fewer than 50 Chinese were allowed into the country. Now, at the newly opened Chinese Canadian Museum, in Vancouver’s Chinatown, the inaugural exhibition, “The Paper Trail to the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act”, tells these harrowing stories, which emerge through long-lost immigration documents.

Melissa Karmen Lee, chief executive officer of the museum, says the exhibition is a powerful reminder of a chapter in Canadian history still unfamiliar to many.

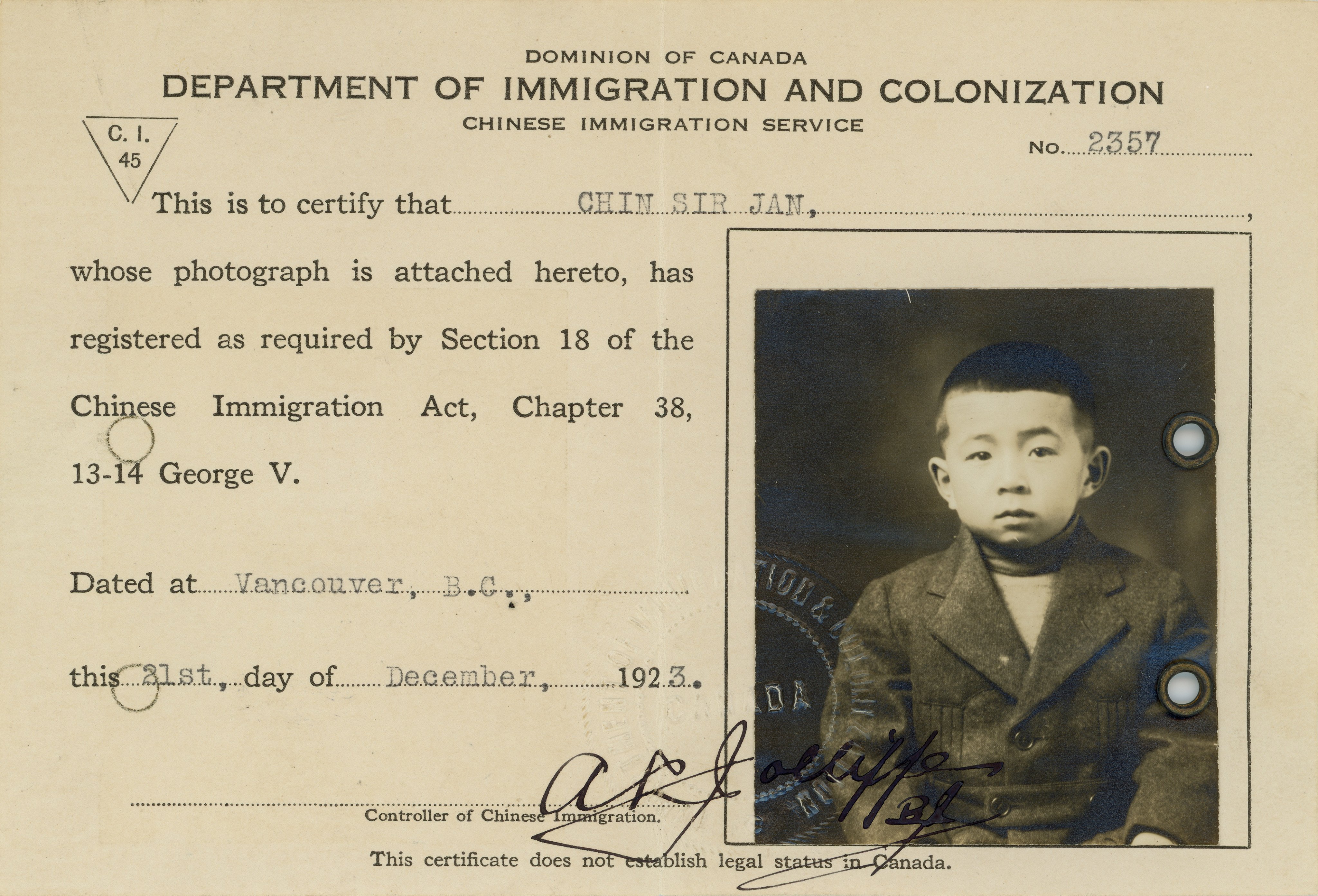

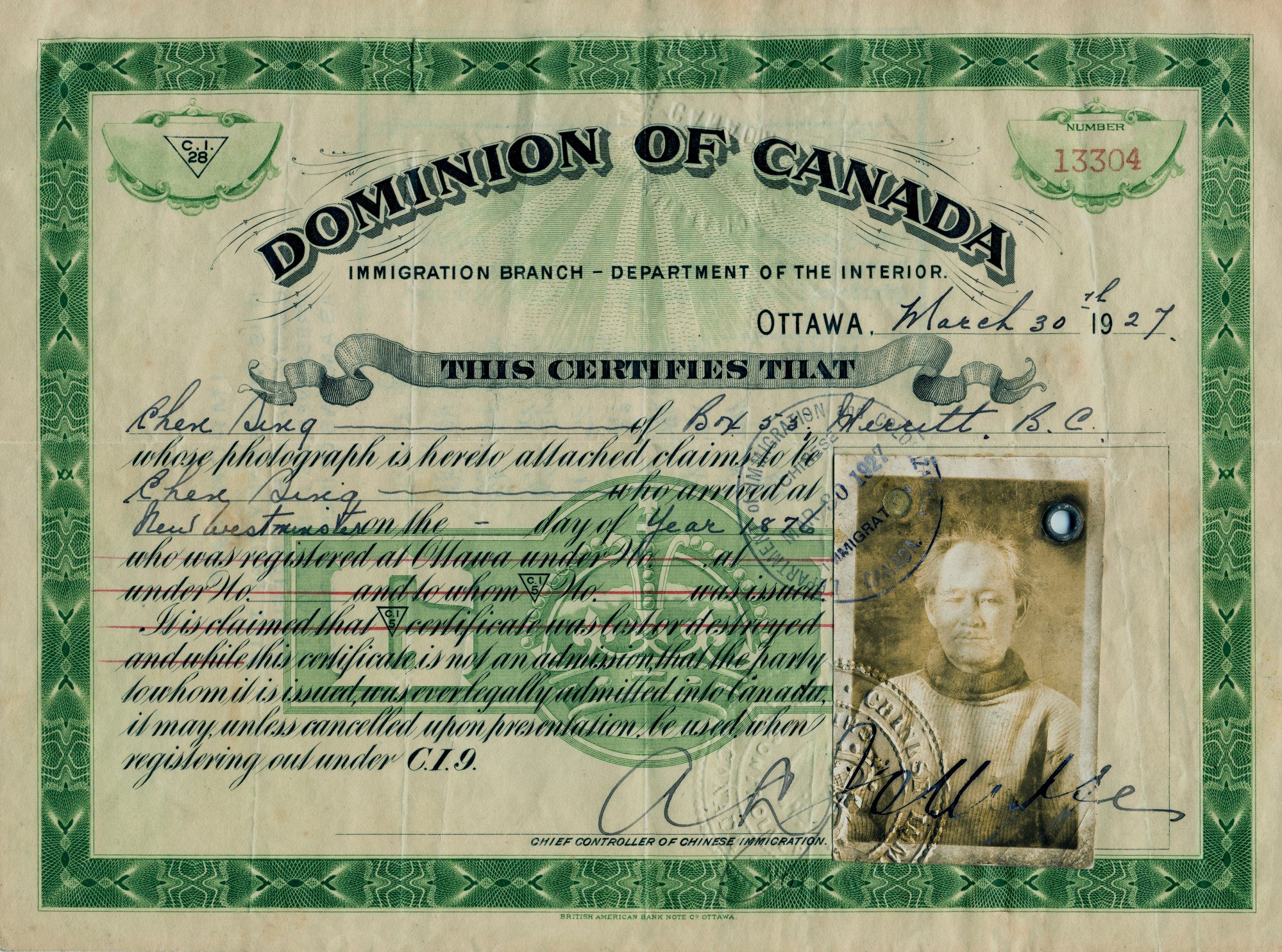

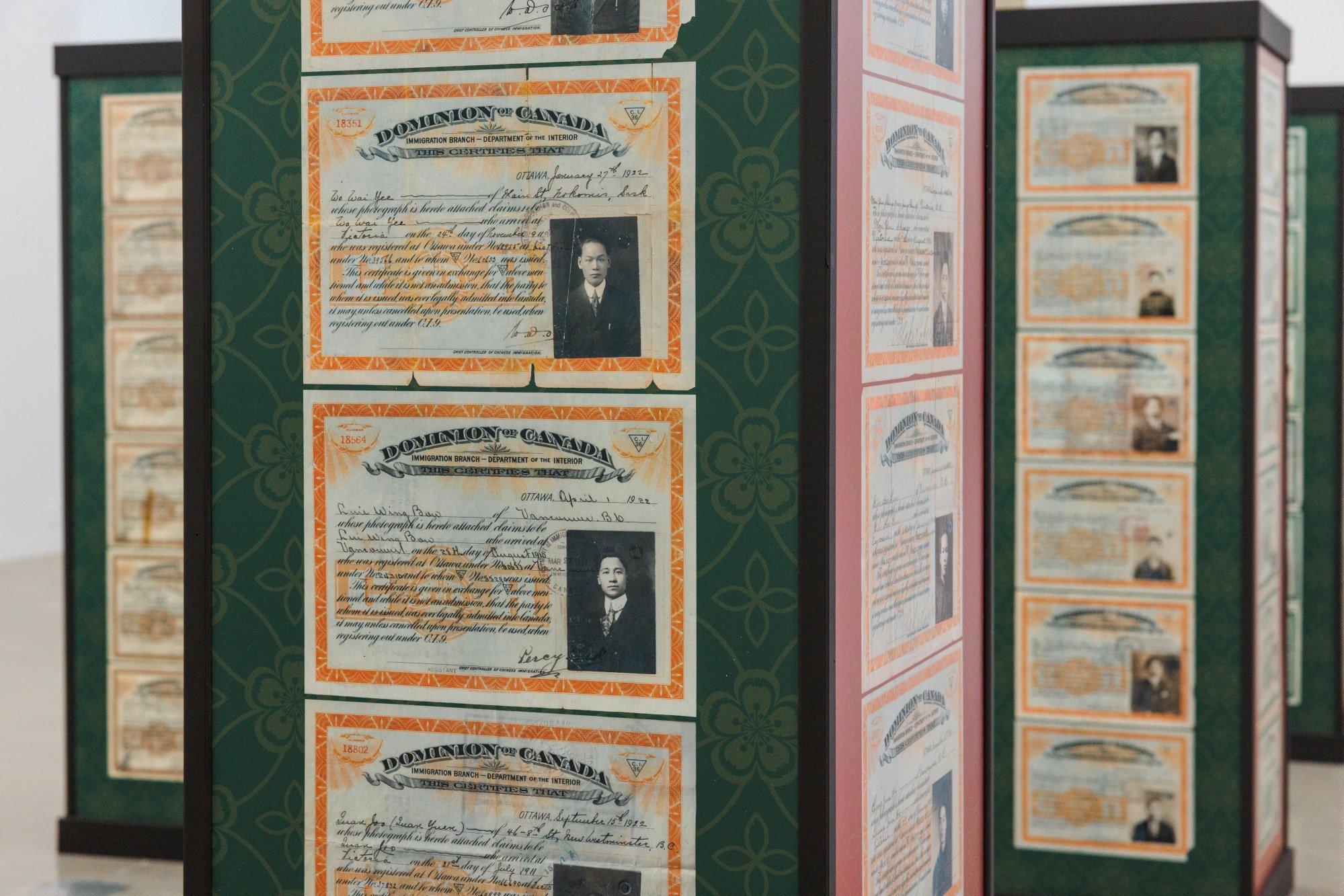

Chinese Immigration (CI) certificates, now time-worn pieces of paper, are evidence of how the Canadian government forced those Chinese who had come to the country to make a better life for themselves and their families to choose either to return to China for good or stay, and suffer further indignities.

Even those born to Chinese parents in Canada had to register for CIs.

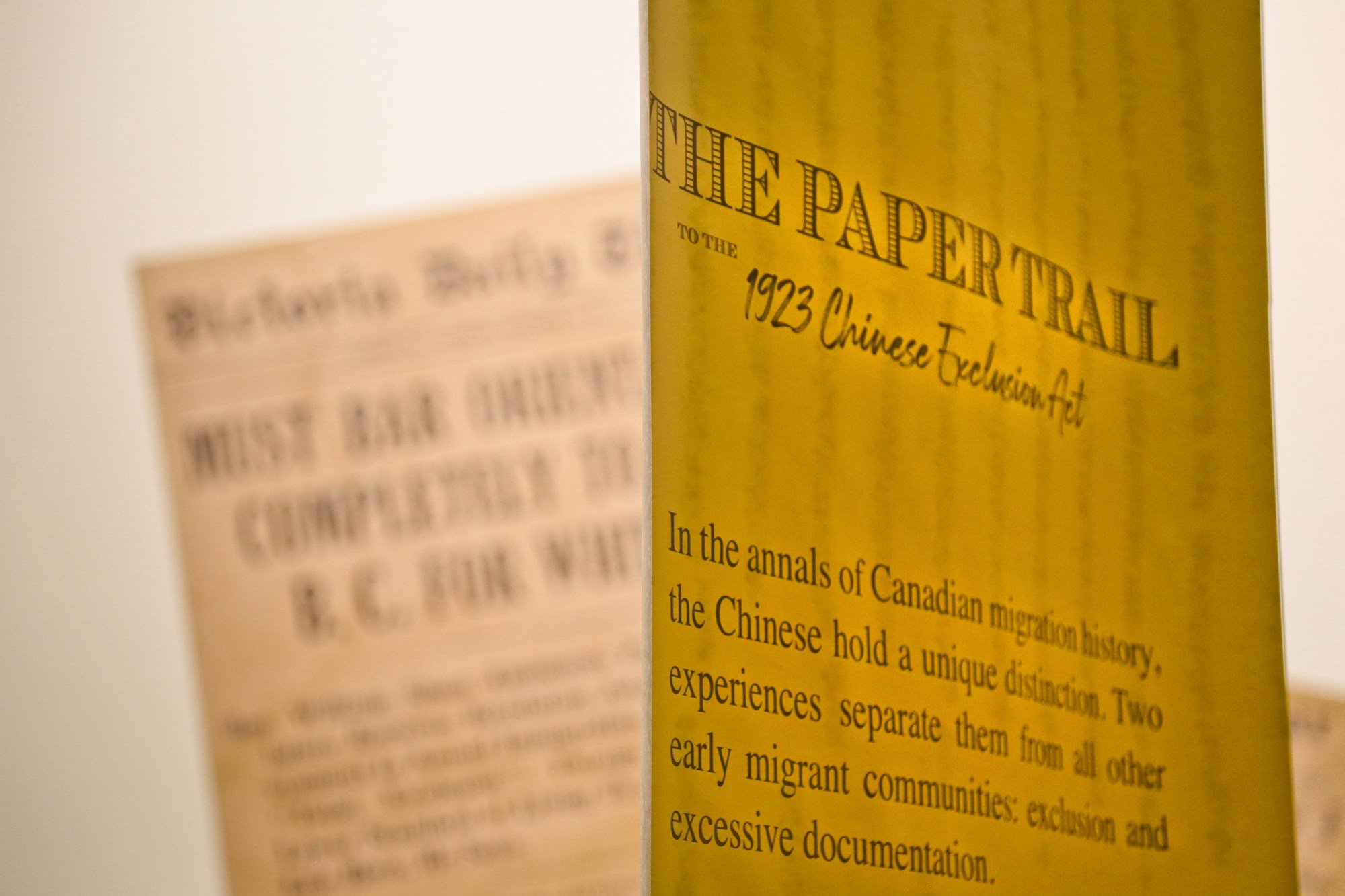

“In Canadian history, the Chinese hold two unique distinctions that separate them from all other early migrant communities: exclusion and excessive documentation,” says Catherine Clement, guest curator for the exhibition.

“This is the story of the Chinese community’s darkest period in Canada, told through the voluminous paper trail it left behind.”

So, even decades before the 1923 Exclusion Act, every Chinese person – the vast majority of whom were men – entering the country was made to pay C$50, and what would become known as the “head tax” was later raised to C$100 and then to C$500 by 1903.

The Canadian government, meanwhile, continued to find ways, as Clement says, to enforce the “slow squeeze of exclusion”.

This included prohibiting labourers from entering the country and reducing the age at which a child could come in, while provincial and municipal governments passed laws determining where Chinese people could live, what kind of property they could buy and where they could open businesses.

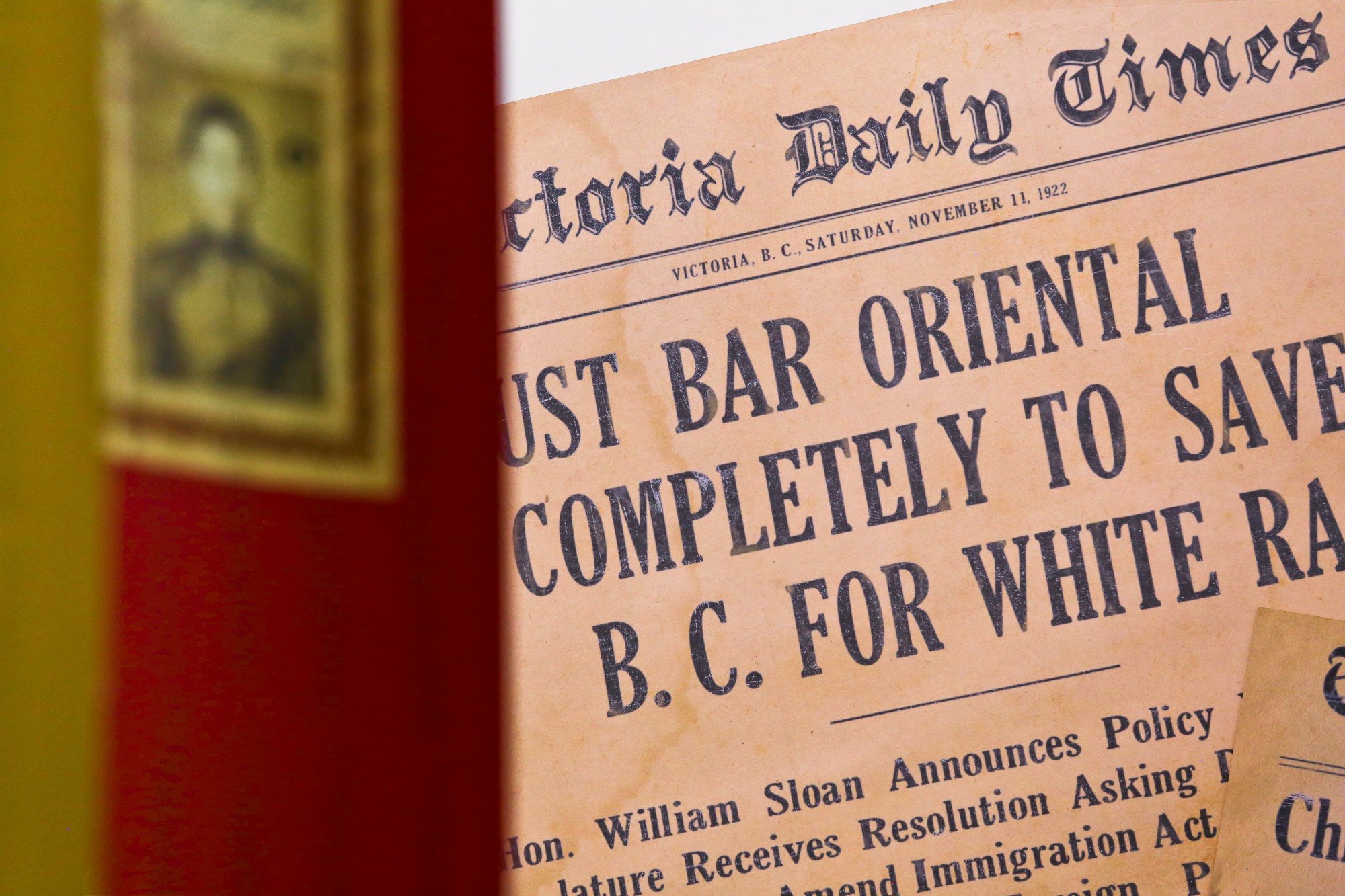

On November 11, 1922, the front-page headline of the British Columbia capital’s newspaper, the Victoria Daily Times, read: “Must Bar Oriental Completely to Save B.C. for White Race”.

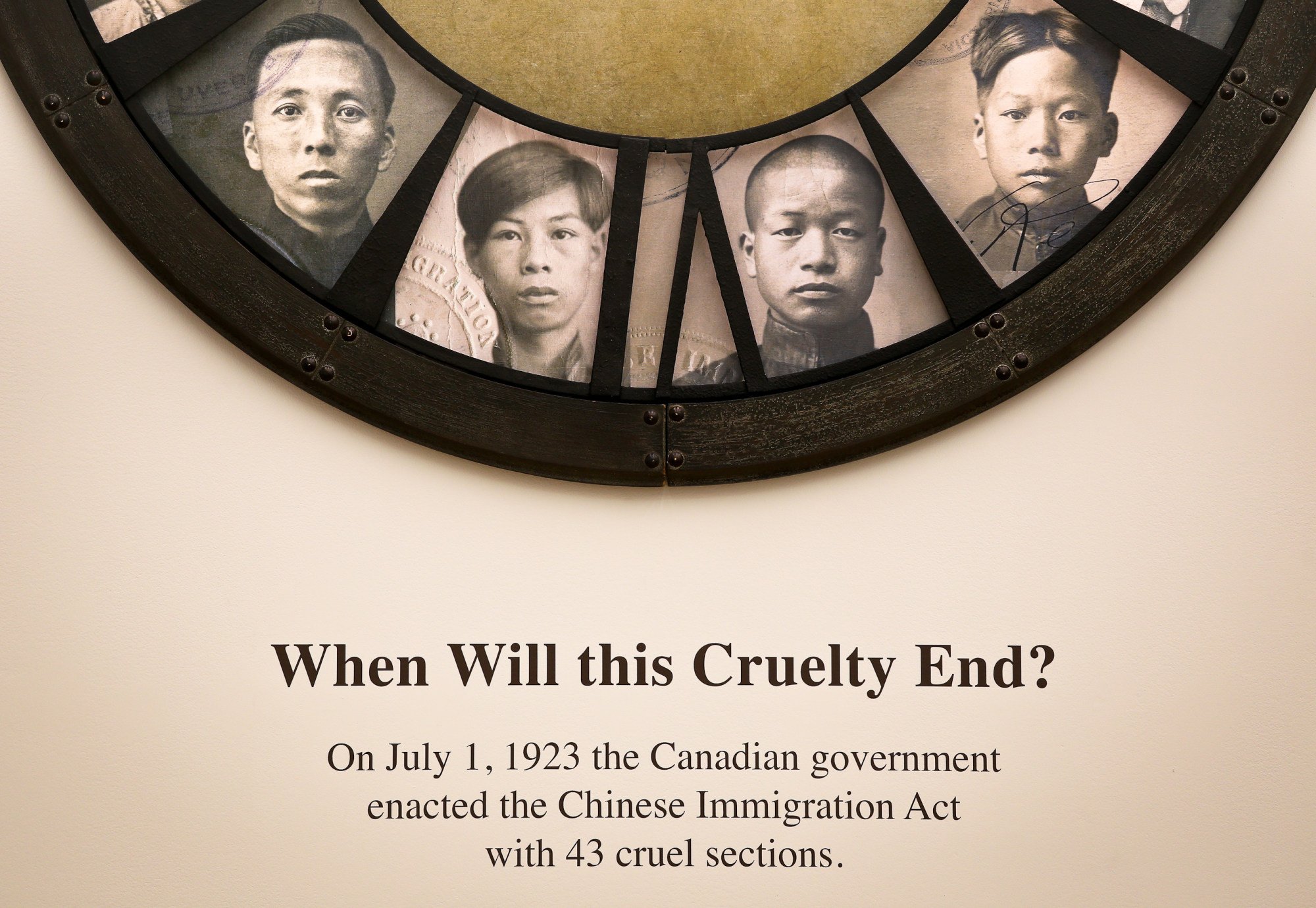

The Canadian government put an end to Chinese migration completely with the Exclusion Act on the country’s national day, July 1, 1923.

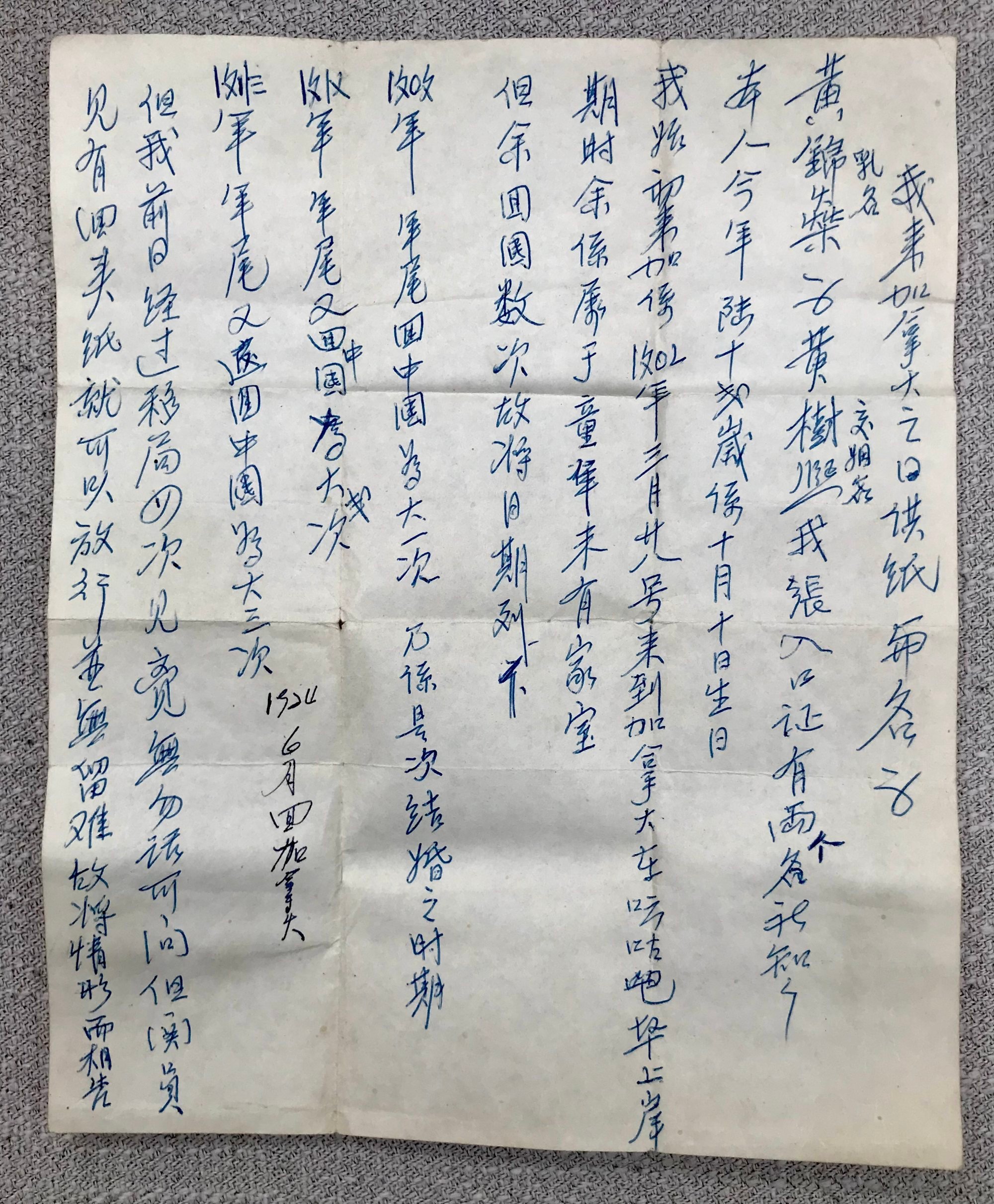

Authorities gave the Chinese community a year’s notice to register at an immigration office or a Royal Canadian Mounted Police detachment. And while much was known about the 15-page law itself, there was little knowledge of the effect it had on the Chinese: would they register and stay in Canada? If they wanted to go back to China, did they have enough money to pay for the long journey?

“We discovered that it was actually the registration that the community most feared because they were going to be interrogated,” says Clement.

“They were concerned [they may be deported] if they didn’t remember everything according to what the government had recorded [of them], or [if they had come] in as a child and didn’t know what their details were at the time, or came in as a merchant and then the business failed.”

In stories published from July 1, 1923 to June 30, 1924, the Chinese community described it as the “cruelty act”. For the Chinese, Canada Day 1924 was “Humiliation Day”, which they marked with displays of white floral wreaths in shop windows, or by lowering the Canadian flag to half mast.

Clement, along with other researchers able to read Chinese, found newspaper articles that showed the despondency and desperation among the Chinese.

When I grew up, we didn’t talk about that. Nobody talked about it, nor would they tell usBev Wong

A shop owner in Lethbridge, Alberta, one day flung open the doors to his silk-goods store and told people to take whatever they wanted. There were numerous short news items detailing Chinese men who had committed suicide, leaving notes saying they were “tired of life”.

“At least with the head tax, there was some hope,” says Clement. “It wasn’t a totally closed door. This really changed everything. But basically we found most people accepted what would happen.”

As a result of the exclusion that separated Richard Wong’s grandparents, men even less lucky became known as the “bachelor society”. Many such elderly men sewed money into their clothes so that, if they were found dead, there were enough funds for a burial.

By June 30, 1924, there were 55,982 ethnic Chinese, both migrants and those born in Canada, registered with the government.

More than half of them, 31,328, were in British Columbia, followed by 8,395 in Ontario, 4,668 in Alberta and other provinces, with the Yukon home to just three. More than 48,000 of those were men, 1,300 were women and 6,200 children.

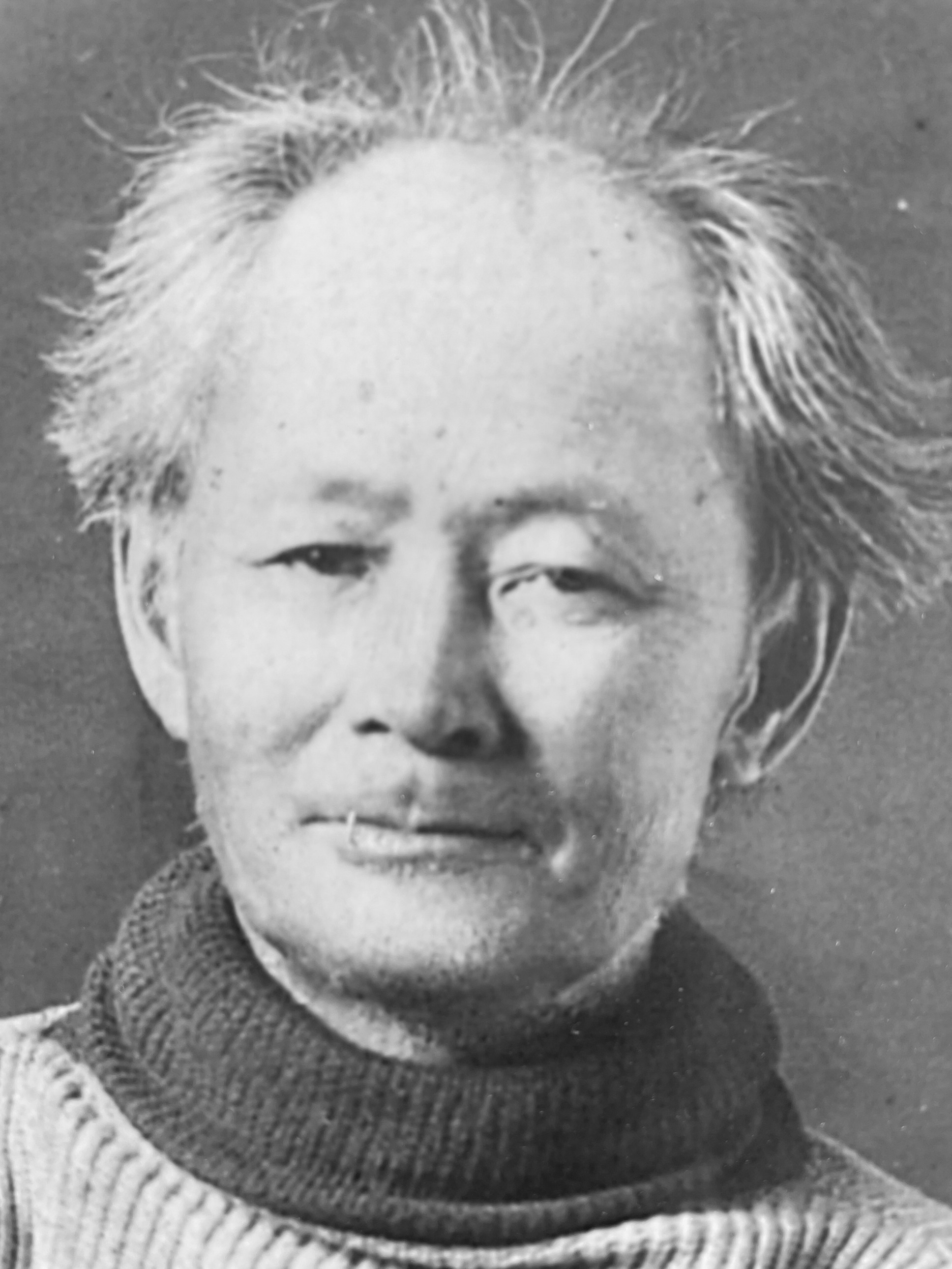

When Clement put out the call for the CI documents, Bev Wong (no relation to Richard Wong) went through her late mother’s papers and found not one but two such certificates. One was issued to Ng Yew, her paternal grandfather, the other to Chen Sing, her maternal grandfather.

“When I grew up, we didn’t talk about that. Nobody talked about it, nor would they tell us,” says Wong, 79, of her grandparents’ experiences settling in Canada.

Her second-generation parents never told her about the racial and financial hardships her grandparents faced, because they didn’t know either, and they were keen to integrate into the community, as was Wong’s generation.

Not until many years later did Wong learn more about Chen and his life in British Columbia, which was fictionalised in a 2017 children’s book called The Railroad Adventures of Chen Sing, by George Chiang.

Born in China around 1860, Chen was an orphan who grew up in poverty. One day, he heard of an opportunity to help build the Canadian Pacific Railway in British Columbia.

Arriving in 1876, he worked as a tea boy, bringing tea to Chinese railway workers and earning C$1 a day. Such low pay meant clearing the C$800 debt he owed a labour contractor to take him to Canada would take years.

Given the lack of Chinese women in the country at the time, Chen was lucky to find a wife. They had six children, all of whom were issued the CI45 cards for locally born Chinese Canadians.

For Clement, the exhibition is a labour of love that began more than a decade ago. Half Chinese herself, she had been interviewing Chinese-Canadian war veterans and their wives.

On learning about the identity certificates, she wondered why they had been issued to people who had been born in Canada. Then, four years ago, knowing the 100th anniversary of the Exclusion Act was approaching, Clement asked Chinese Canadians to search for CI certificates.

Those found and submitted were scanned to create a digital archive. Clement initially planned to create a collage of the black-and-white photographs of the certificates.

“But then as I began to collect these things,” she says. “I realised how little families [knew] about the Exclusion Act […] Often they confused it with the head tax.

“And that’s what led me to think, if I don’t do this on the 100th anniversary, when are we going to do this to really help people understand what that period was about?

“If the head tax was bad, it got worse, and that’s when I started to discover these stories of how people fell apart as a result.”

Of the 56,000 CI certificates issued, Clement has collected 475, many of which are in the exhibition.

The initial certificates didn’t have photographs, but in the early ones that did, Clement notes, the person pictured is usually in Chinese dress, and over the decades they become more Western in their appearance.

It’s about remembrance: remembrance of those who came before us, remembrance of the price people pay to be hereCatherine Clement, curator

The photographs of babies and children were cut out from formal family photographs. While many were printed in green, others were brown and orange, depending on the period of issue.

For the CI45s issued from 1923, the beige cards had the person’s photograph, name typed on the card, and on the bottom was written: this certificate does not establish legal status in Canada.

“One of the Chinese-Canadian veterans, Gim Wong, used to get so angry,” says Clement. “He said, ‘You know, there’s dozens of ways they could have registered the Canadian-born children. But they chose to give us a card because they wanted to transfer exclusion […]

“They couldn’t do it legally. But you could do it symbolically by putting on a card that they didn’t have sound legal status in Canada.’”

The 475 CI certificates will be archived at the University of British Columbia, in the hope that more of them will be found and preserved, along with the stories of the people who held them.

At Clement’s urging, on July 1 this year, Library and Archives Canada released the database of the 55,982 names recorded during the Exclusion Act, a big help for Chinese-Canadian families trying to find out whether any ancestors were so registered.

“From an emotional point of view, it’s about remembrance: remembrance of those who came before us, remembrance of the price people pay to be here,” says Clement.

“To me, it’s like one generation paying tribute to another. And even if you’re not connected to it, you’re still a beneficiary of every single person who soldiered on. I don’t know if I could live in a place that really disliked me that much.”

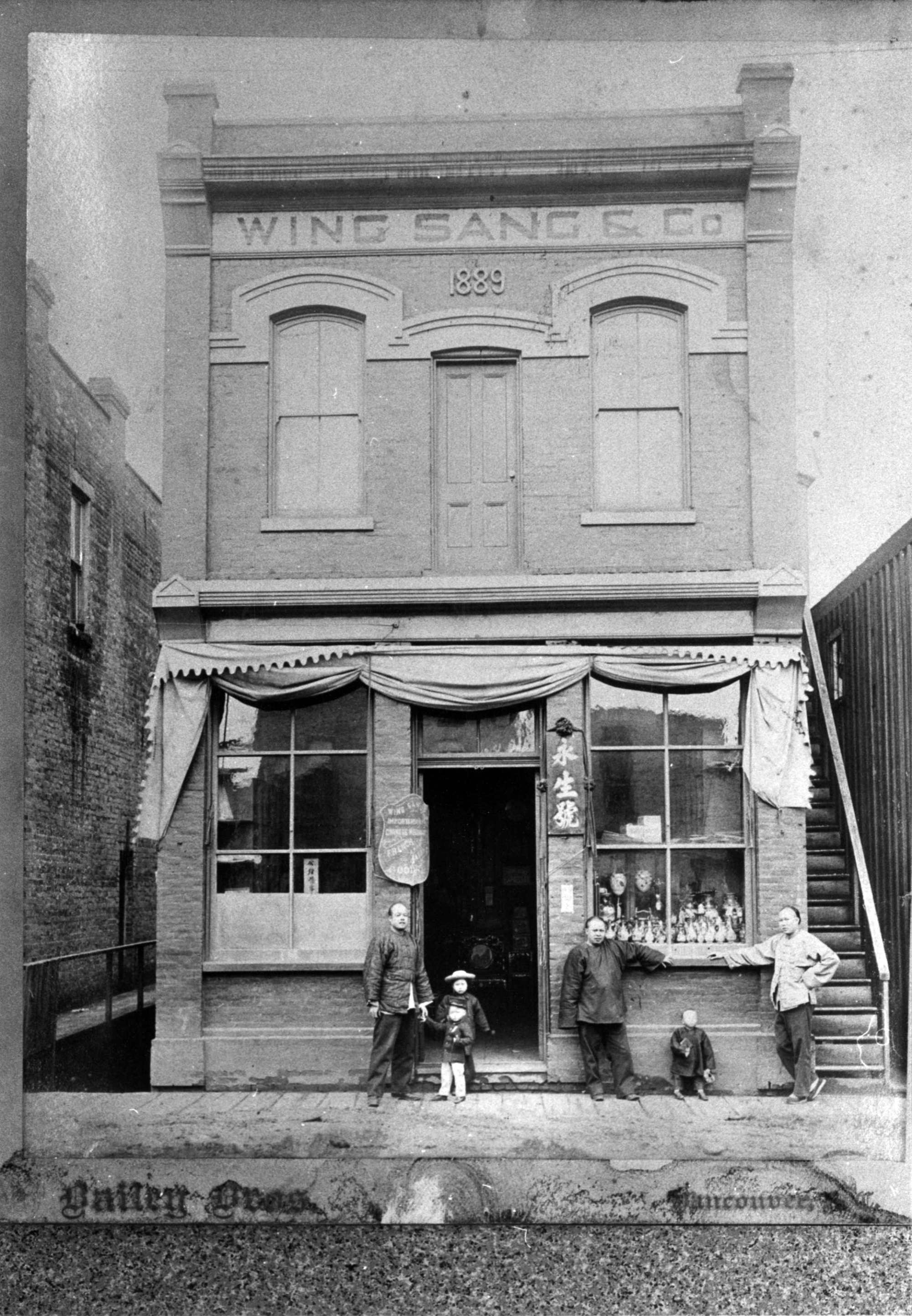

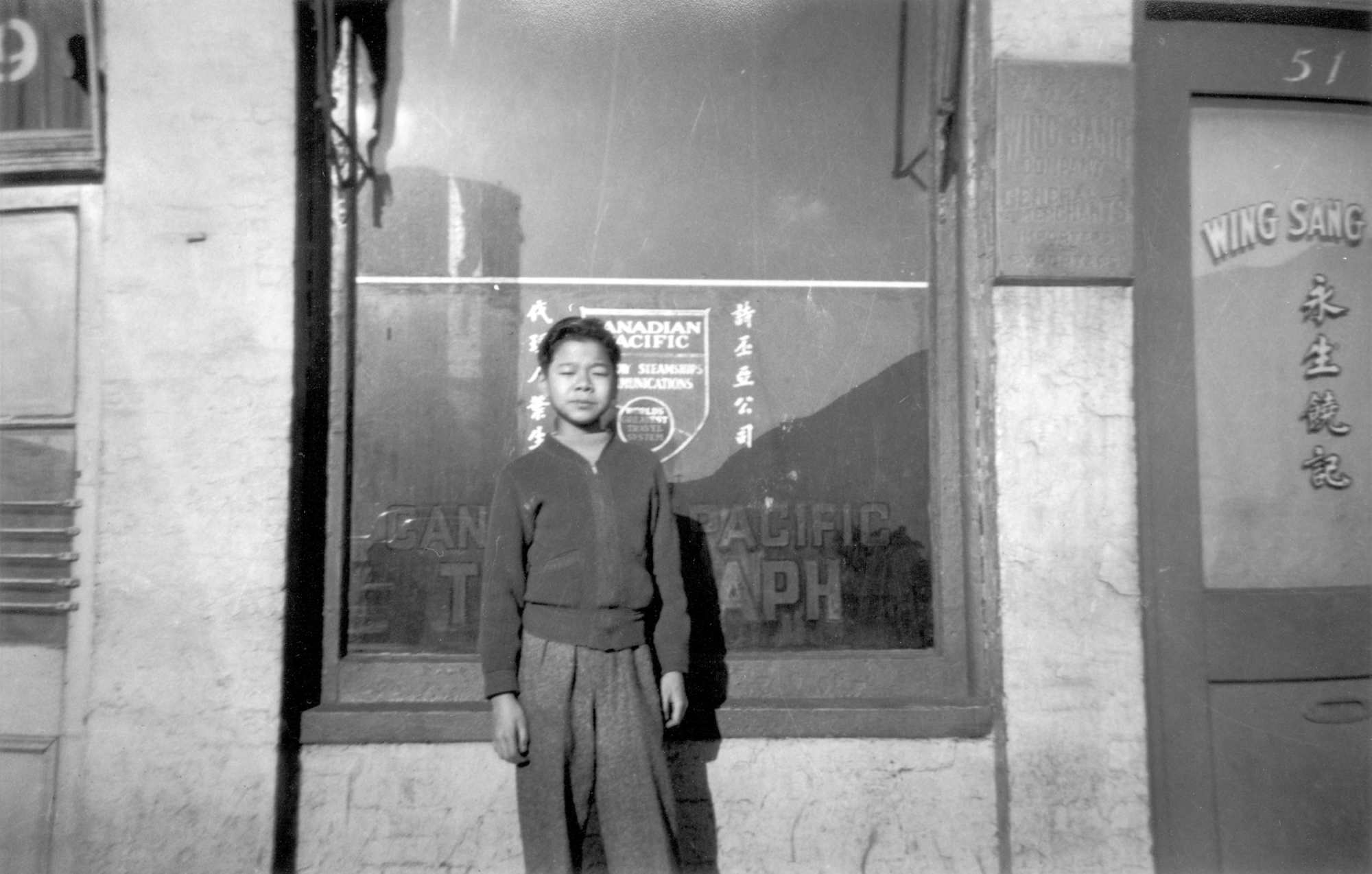

One of his grandsons, Mel Yip, now 88, spent the first 15 years of his life living in the building, and has fond memories of playing with his numerous cousins there, going to the cinema together, giving new year greetings to his elder relatives and collecting lai see envelopes at the stroke of midnight on Lunar New Year.

“He was like a bank,” says Mel. “Since he had an office in Hong Kong, he would send money back and the [customer’s] family would pick it up there. And also the mail would come to Wing Sang. I remember those slots, the Chinese people would come in and mail would come from China or Hong Kong.”

Yip Sang not only had an import-export business in kitchen utensils and fabric, he also owned two fishing boats and a few canneries.

“He was quite well off. But he passed away in 1927, [just before] the Great Depression. His sons were in the business, looking after the fish boats, looking after the canneries, and things like that.”

One of Mel Yip’s uncles, Kew Dock Yip, studied law and became the first Chinese-Canadian lawyer in far-off Toronto – he would not have been allowed to practise law in British Columbia.

In 2022, the government of British Columbia helped the Chinese Canadian Museum buy the Wing Sang Building from then owner Bob Rennie, a well-known real estate marketer, who also donated to the museum. The federal government and the City of Vancouver also pitched in funds.

On June 23 this year, the Canadian government commemorated the 100th anniversary of the passing of the 1923 Exclusion Act with the unveiling of a plaque at the Senate Chamber in Ottawa.

Steven Guilbeault, minister of environment and climate change, said he was honoured to commemorate the significance of the exclusion of Chinese immigrants.

“I encourage all Canadians to learn more about the impacts of the Chinese Exclusion Act and this defining era of Canadian history as we work to continue building a Canada that is as welcoming as it is diverse.”