- In 1971, during the Cultural Revolution, Beijing sent a Chinese ballet film to the glitzy Venice Film Festival, from where it become a hit with Western audiences

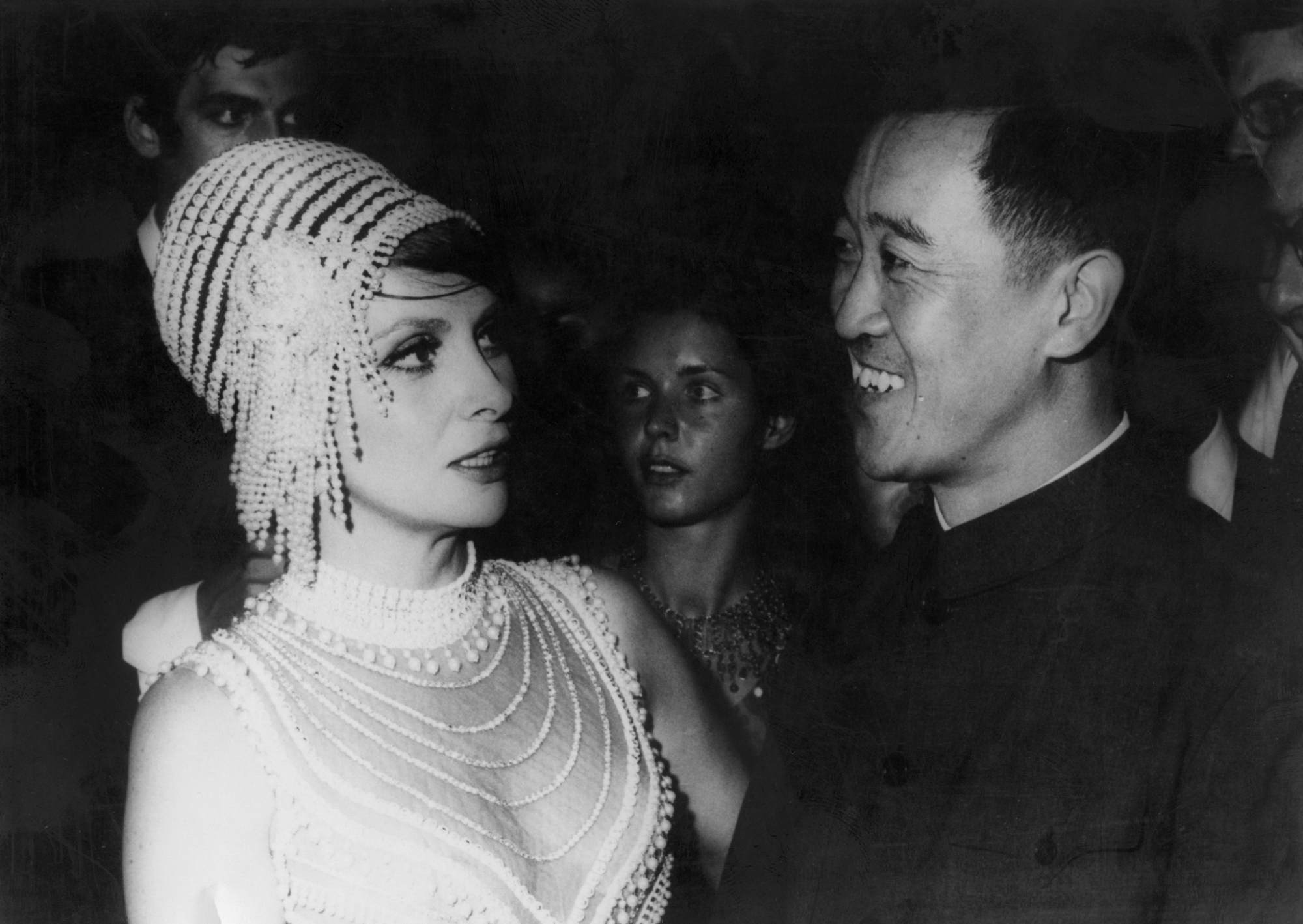

Gina Lollobrigida, one of the big stars of Italian post-war cinema and a Hollywood icon, was the public face of the 1971 Venice International Film Festival.

Surrounded by fans and paparazzi, she was clad in a revealing bead-encrusted gown and matching cloche hat. Looking every inch the movie star, Lollobrigida was caught in conversation with a clearly charmed Chinese man wearing a navy blue Zhongshan suit and looking every inch the dedicated Maoist.

The picture is all the more remarkable when you consider that the 1971 festival was one of the most lavish star-studded gatherings of the international film world in a western European city renowned for its love of money and excess.

Who was he? Why was Gina Lollobrigida entertaining him? How did this photograph even happen at the apex of the chaos and ideological madness of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution back in China?

Well, it turns out that in 1971 – a year that would see both the deadliest factional infighting among the Chinese leadership and the tentative beginning of moves towards rapprochement with the United States – the People’s Republic of China and Italy, after many years of wrangling and rancour, officially established diplomatic relations.

It was decided to send The Red Detachment of Women (1970), a lavish, full-colour filmed performance of a ballet based on a 1961 movie of the same name, on a tour to Europe, Australia and North America.

The Red Detachment of Women was one of the eight “model operas” that came to prominence during the Cultural Revolution and remains arguably the most famous Chinese dance work today.

She subsequently becomes a Red Army soldier, kills the evil Nan Batian and then devotes herself to furthering the aims of the revolution as leader of a women’s militia.

The original 1961 Red Detachment, directed by Xie Jin, was an instant box office hit in China. It was choreographed as a ballet in 1964, adapted as a Beijing operatic piece in 1966 and ultimately classified as one of eight official geming yangbanxi (“revolutionary model theatrical works”).

How art helped spread Maoism around the world

In 1970, Beijing Film Studio recorded a performance of the ballet and released it as a film. Directed by Pan Wenzhan and Fu Jie, The Red Detachment was spectacular, certainly by the technical standards of the Chinese film industry at the time.

It starred Xue, then prima ballerina of the National Ballet of China, alongside Liu Qingtang. Liu, who had studied in the Soviet Union, became a household name in China after starring in a production of Swan Lake as Prince Siegfried.

Xue, in particular, was singled out for praise, not least because the role required her to be on stage, performing, for more than half the length of the ballet.

It seems someone at Beijing’s Bureau of Culture thought it might be a good idea to send the film out on tour – to the decadent capitalist cities of London, Sydney, New York and San Francisco. The tour was to kick off with a premiere at the 32nd Venice International Film Festival.

By the 1960s, the festival was the highlight of the Lido di Venezia’s summer social scene, with screenings held in the ultramodernist Palazzo del Cinema di Venezia.

It was by now a luxurious annual fête of champagne receptions and star-studded galas that attracted Hollywood movie stars and moguls, the cinematically inclined intelligentsia of Europe, and surprisingly, in 1971, a delegation from Maoist China.

Despite its reputation as symbolising just about everything the Cultural Revolution stood against, there were several factors that led the Bureau of Culture in Beijing to opt for Venice.

Secondly, in late 1970, the People’s Republic and the Italian Republic finally recognised each other after 20 months of secret negotiations in Paris. They agreed to swap ambassadors following a two-decade break in relations.

But by 1970, these stumbling blocks were either overlooked or ironed out, ambassadors were dispatched east and west, and much political capital was made by the new relationship.

Rome smoothed the application process and The Red Detachment was invited to Venice, the first movie from the People’s Republic ever to show officially at a Western film festival.

And so The Red Detachment screened alongside the other selected films, which that year included a tale of witchcraft and sexually repressed nuns from Ken Russell (The Devils); the story of a jilted mistress, played by Vanessa Redgrave, committed to an insane asylum who escapes and finds happiness with a troupe of gypsies (Tinto Brass’ La vacanza); Dennis Hopper’s metafictional Peruvian Western (The Last Movie); and an Iranian story of a man who goes insane and believes he is a cow (Dariush Mehrjui’s The Cow).

Chinese museums’ loan of art and artefacts to US counterpart is a landmark

Probably the only movie the rigid Beijing Bureau of Culture might have tolerated was a film version of Welsh poet Dylan Thomas’ tale of the everyday inhabitants of a proletarian fishing village, Under Milk Wood, starring Richard Burton, Elizabeth Taylor and Peter O’Toole. And … The Red Detachment of Women.

But not everyone was happy. Gian Luigi Rondi, a film critic for the right-wing newspaper Il Tempo, had been chosen as the festival’s director, so a group of left-wing Italian filmmakers called on their international colleagues to boycott the event.

They assumed that even if their plea fell on deaf ears in Hollywood, surely it would not in Beijing. But it did. The Chinese delegation were coming no matter what. European leftist politics, it appears, didn’t interest them much.

Beijing’s Bureau of Culture was probably busier in the summer of 1971, at least in terms of booking overseas phone calls and sending international telegrams, than it had been for the five years since the start of the Cultural Revolution.

Any nascent overseas artistic engagement that had begun after 1949 had come to a shuddering halt in the mid-1960s. The overseas tour of The Red Detachment was the most major endeavour the bureau had undertaken to date.

Both the Bureau of Culture and the Foreign Ministry had seen their operations severely disrupted since the start of the upheaval. China had become increasingly inward-looking and obsessed with domestic politicking.

Meanwhile, in Venice, there had been a minor snafu when the Chinese delegation found out that they were not the only ballet in town.

Bonaparte, a ballet filmed for French television and choreographed by Serge Lifar, a Russian émigré and former principal dancer with the Ballets Russes, was also screening. Lifar, the veteran director of the Ballet de l’Opéra national de Paris, was a cultural celebrity who, Beijing could not have failed to notice, had left Soviet Russia in 1921 to go into exile.

The part of the diminutive French dictator was danced by the prima ballerina Ludmilla Tchérina, who also came from a family that had fled the Russian Revolution for France. A small hiccup, but ultimately of no matter.

Macau dates for viral ballet based on Song dynasty painting

When it came to write-ups it was The Red Detachment that was by far the most talked about of the two ballets, all the more surprising as festival director Rondi’s selections were not, by and large, to the critics’ tastes.

Ian Cameron, founder and editor of the serious and intellectual Movie magazine (once called the English-language Cahiers du Cinéma), wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “The festival managed to achieve a sort of balance – the weather was great, but the movies were terrible.”

Under Milk Wood was “deplorable”, The Devils “a fetid effusion”, even a film from the much-admired darling of European cinema Ingmar Bergman was criticised for having already been out for two years, meaning everyone had seen it.

However, he considered The Red Detachment to be “exciting”, even if “surprisingly the art of revolutionaries tends to be extremely conservative”.

Most other critics, European and American, agreed with Cameron. Few movies at the festival appealed to Jeanne Miller, a film critic for the San Francisco Examiner, but she did find The Red Detachment fascinating, if a little long.

She claimed to have been “stunned” by the impressive cinematography and the balletic battle scenes in which the troupe of dancers arabesque and jeté with rifles.

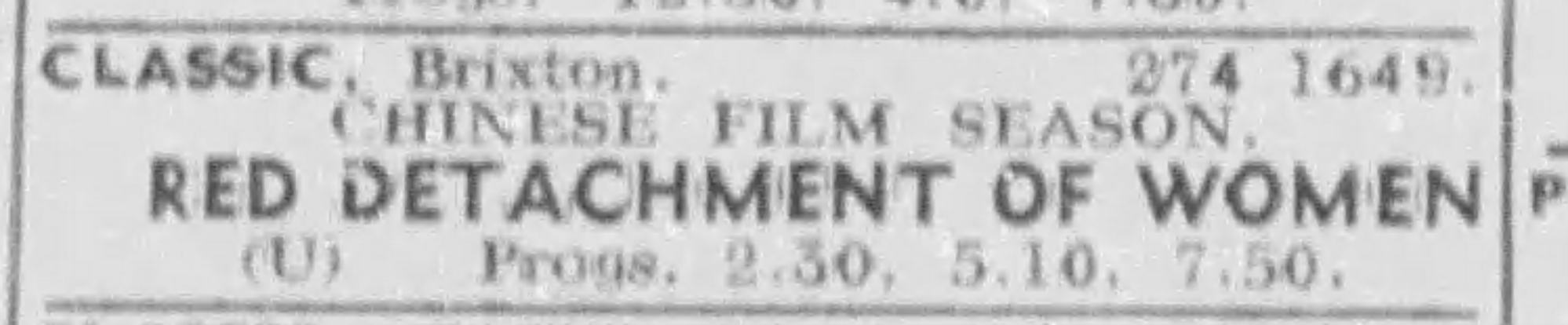

After Venice The Red Detachment went on tour, screening at independent art cinemas in cities from London to San Francisco.

The Classic chain of cinemas in London held a Festival of Chinese Film, sponsored by the generally pro-Beijing Society for Anglo-Chinese Understanding, which had been established in 1965.

Some cartoons and a couple of documentaries – Red Flag Canal, about an irrigation project in Henan province, and another on the building of the bridge over the Yangtze at Nanjing – rounded out the festival.

The Red Detachment was the most popular offering, running three times a day for four days to apparently full houses.

The London critics also gravitated more to the acrobatics and sheer balletic skills of Xue, Liu and the rest of the cast. They liked the combination of traditional ballet and Chinese folk dancing.

Judith Cook, a film critic at The Birmingham Post, found the elevation of “the virtues of collective action” refreshing after the usual Western film ethos of “individual characterisation”.

And, in a quote that recalls the particularly nicotine-addled flavour of London cinemas in 1971, “even in the smoky comfort of a London cinema, The Red Detachment of Women comes across with great force and conviction”.

According to film historians Kirsty Sinclair Dootson and Zhu Zhaoyu, it appears that the Chinese government bought expertise and equipment from Technicolor in the early 1970s to establish the firm’s dye-transfer process at the Beijing Film Laboratory, though the supposedly obligatory “Color by Technicolor” logo was never added to the film credits.

Other prints of the film had been sent to Australia and North America. The Australia-China Friendship Society arranged screenings in Sydney and Melbourne.

Four hundred local worthies sat down in Ottawa to watch the film. They were all guests of Huang Hua, the Chinese ambassador to Canada.

The film ran to reportedly packed houses in San Francisco and attracted “a line” outside a cinema on the Upper West Side of Manhattan.

Perhaps it was diplomatic politeness in Ontario or left-wing students in London, New York or San Francisco that were filling the cinemas.

‘Let’s start from scratch!’: Chinese artist who changed meaning of crosses

Betty Dietz Krebs, the Dayton Daily News’ fine arts editor in distinctly un-left-wing Ohio, wrote that a full house was witnessed for the showing of The Red Detachment in Yellow Springs, admittedly a college town with something of a reputation for being a hippy village, but not perhaps where a “Red Chinese” movie might be expected to be a hit.

While admiring “the physical accomplishments of the dancers”, Dietz Krebs seemed a little disconcerted that after three sell-out screenings a fourth had been added.

What Beijing’s Bureau of Culture hoped to achieve with the Western tour of The Red Detachment is not recorded.

The Red Detachment offered curious new audiences a glimpse of revolutionary art from China, and while the film might not have changed many political opinions, it was an intriguing aesthetic and the balletic skills were undeniably impressive.

The Red Detachment of Women remains part of the permanent repertoire of the National Ballet of China. It has been performed more than 4,000 times in the past 59 years.

Xue, who is now in her late 70s, danced the ballet for United States president Richard Nixon when he visited China in 1972.

She taught dance for many years at the Huaxia Art Centre, in Shenzhen, and also appeared as a judge on the 2002 China Central Television (CCTV) show Dance Competition.

The Red Detachment of Women films are still regularly shown on Chinese television, often to mark International Women’s Day.

In many ways The Red Detachment is a period piece, a curiosity from a complicated time in China’s history that is now on the fringes of living memory.

The Guangzhou hotel bomber whose anti-colonial spirit inspired Ho Chi Minh

But we can also sense how different and visually stunning the film would have appeared to Western audiences in 1971.

Women take centre stage in the tale, a classical elite art form is fused with proletarian messaging.

It remains as captivating now as it was when it premiered before its first international audience at the Palazzo del Cinema di Venezia a half-century ago.

We know that the new Chinese ambassador to Italy, Shen Ping, was in Venice and sat next to Redgrave for a screening.

The British actress, at the time a very vocal Trotskyist, may well have been too left-wing for the ambassador’s tastes. But there is our man again in the row behind Redgrave.

For now, he remains an enigma.