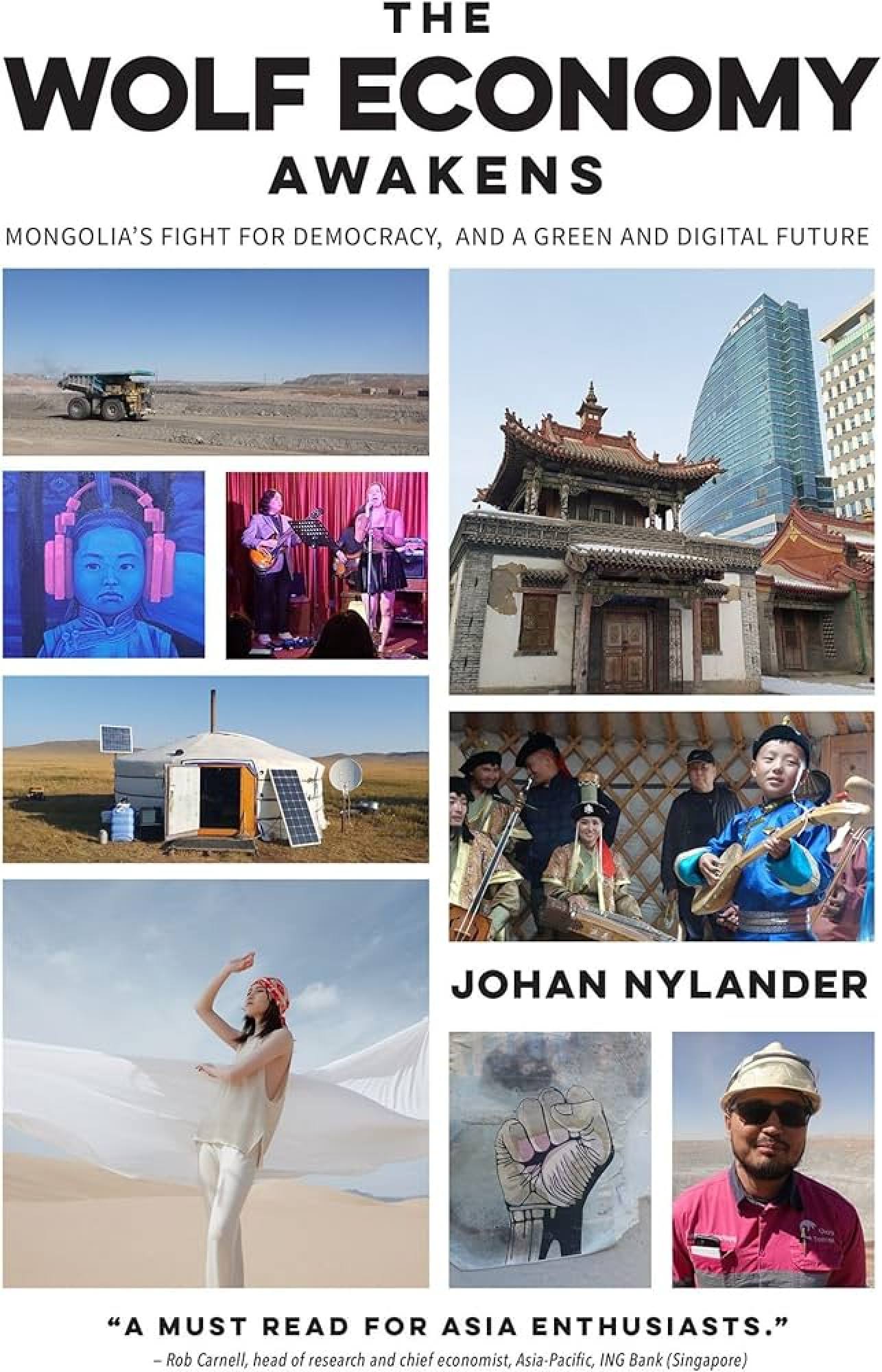

- On the Mongolian steppe, nomads are embracing digitalisation to stay connected and do business without sacrificing the best of their traditional way of life

Out in the wilds of the Mongolian steppe, nomadic herders are embracing the information age. In this excerpt from his book “The Wolf Economy Awakens”, author Johan Nylander looks at how the internet is rising to the challenges of tradition.

The door swings open to the nomadic tent in which we’ve spent the night. A man pops his head inside the room and asks, enthusiastically, “Wanna see gazelle?”

I roll out of bed, grab my boots, and run after Batbayer, our host. He points to a bright green and sun-soaked hillside a short distance away. But there isn’t just one Mongolian gazelle. At least a hundred of these medium-sized antelopes are on the move, slowly and gracefully, and seemingly unconcerned by the humans gazing at them.

For the local nomads, such scenes are not uncommon. But for this outsider, it’s a magical moment. Then, from the opposite direction, another group of animals comes strolling toward us, equally uninterested in our presence although without the gazelles’ effortless grace.

It’s Batbayer’s flock of sheep, baaing and munching on grass as they go. In less than an hour, the gazelles and sheep have moved on to new valleys, beyond our sight. Batbayer has a cheerful face, but with the deep creases and leathery tan that come from long hours working outdoors, giving him the look of a sailor from an Ernest Hemingway novel. He lives with his wife, Enkhmaa.

Together with his brother, they own much of the livestock they look after as they wander the vast Mongolian landscape.

Out here, there are no other people around. The steppe of the northeastern Khentii province seems to stretch endlessly in all directions, making the world feel bigger but also somehow simpler. It’s only now that I feel I truly understand what they mean by the “endless blue sky”.

The white nomadic ger is equipped with a television, a satellite dish and some digital devices, and powered with a mix of solar panels and a diesel generator. Parked beside it are a four-wheel drive and a motorbike.

Apart from such conveniences, however, the family is entirely at the mercy of nature.

I ask Batbayer if he’s worried that the sheep will run off. There are no fences here, just land without boundaries. He smiles, explaining patiently to the naive city boy that the flock roams freely, typically returning in the evening or the following day.

This reminds me that he mentioned the previous evening that he and his brother also had horses.

Where are they? Pointing in a wonderful everywhere-and-nowhere gesture, he says he hasn’t seen them for three months.

“They like to wander around,” he says. “It makes them happy. But they always come back, or I’ll find them with help from friends.

“Sometimes,” he adds, his sunburned face beaming, “there are more of them when they return because they’ve had foals.”

Mongolia is home to one of the world’s few remaining truly nomadic cultures. About a fifth of the population are herders, and nomadism is intricately woven into the country’s very spirit.

Even its modern-day democratic values can be seen as reflecting Mongolia’s nomadic traditions – freedom, independence and pluralism.

I would never choose Facebook over the well-being of the animalsBatbayer, Mongolian herder

This way of living and interacting with animals and the natural environment – and having respect for both – is not easy for an outsider to fully comprehend.

Spending time with people who live a truly nomadic life is eye-opening. It’s like entering a parallel universe that is barely visible to the untrained eye and that has almost nothing in common with the hectic, urban lives of most of the world’s population.

The United States, with all its wild and open spaces, has 36 people per square kilometre. Japan has 330, Hong Kong almost 7,000.

What’s more, large parts of the steppe have no regular internet connection, liberating life here from the anxiety and stress caused by the intrusions of all-pervasive social media.

After we drained the vodka, Batbayer magically fished out a bottle of Jack Daniel’s, and the atmosphere grew even more jolly. At midnight – to my great surprise – our hosts fired up a karaoke machine and we were soon all dancing to Kazakhstani pop hits and Mongolian love songs, played at full blast under the full moon.

The dogs barked, sheep baaed and millions of stars looked down on us from the infinite depths of the ink-black sky. As I lay in my sleeping bag later that night, I thought about what I had experienced and how far away we seemed to be from “normal” civilisation.

On the Mongolian steppe, life suddenly felt easier – at least from this perspective.

To a tourist on a short visit, being offline feels like a blessing. But for the nomads who live here, digitalisation is fast becoming an important factor in their lives, allowing them to stay connected to friends and family and to conduct business more efficiently.

Picture a tanned Zoomer with a laptop at a beach house in Bali or Goa, most likely earning a living by coding, selling stuff online, trading crypto or writing.

But in Mongolia, there are real digital nomads. In many parts of the countryside, Mongolia’s nomads are adapting to modernity – and the technology that underpins it – in their own unique ways, without sacrificing the best of their traditional way of life.

Livestock-based agriculture has traditionally been a backbone of Mongolia’s economy and society. However, the country’s nomadic way of life has come to be menaced by shifts in temperature and weather patterns, as well as neglect and bad management.

Climate change is a major culprit, and Mongolia is already suffering more than most parts of the world. Average temperatures increased by 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) between 1940 and 2015, while rainfall has declined, leading to chronic droughts and secondary impacts such as dust storms, according to a 2021 report by the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank.

This puts the nation’s unique ecosystem under pressure.

“Here on the central Asian steppe, the ancient home of Chinggis Khan and his Mongol horde, the nomads are brought up tough,” The Washington Post wrote in 2018. “Yet their ancient lifestyle is under threat as never before. Global climate change, combined with local environment mismanagement, government neglect and the lure of the modern world, has created a toxic cocktail.

“The nomadic culture is the essence of what it is to be a Mongolian, but this is a country in dramatic and sudden transition: from a Soviet-style one-party state and command economy to a chaotic democracy and free-market economy, and from an entirely nomadic culture to a modern, urban lifestyle.”

Digitalisation offers one vital step forward in saving the nomadic tradition. According to Statista, only 12 per cent of Mongolia’s population was connected to the internet in 2011, but by 2021 this had risen to almost 85 per cent.

The government sees telecoms and broadband internet as fundamental to improving standards of living in the countryside – through boosting productivity, sustainability and resilience – and to supporting a fast-growing tourism industry. But it’s not just a case of providing connectivity: electronic government services and a digital literacy programme targeting herders are also being rolled out nationwide.

As Bolor-Erdene Battsengel, a former vice-minister at the Ministry of Digital Development, states: the new inequality is digital exclusion.

The sight of herders on horses or camels accessing web services via their smartphones is no longer as incongruous as it might sound. “The e-Mongolia app has made my life easier,” a herder named Taivansaikhan tells me when we meet in the wilderness of Khentii province, hours from the nearest village.

“I no longer need to go to a government office for different services; I can do it from here. In the beginning, my children helped show me how to use the app, but I’m learning, and I want to learn more.”

He adds that the internet connection is still a bit patchy: he sometimes has to drive his motorbike up a hill to get a better signal and will do all his online tasks while he’s up there. But as long as he can make calls to communicate with other herders in the area, he’s not too worried.

Many of the livestock here – especially the more valuable breeds such as horses, camels and cattle – are now implanted with microchips that can be monitored via satellite-based services offered by companies such as ONDO Space. Herders are also increasingly using drones.

According to a 2019 paper published by Japanese and Mongolian researchers, these can be used to scan soil conditions, monitor the health of crops, estimate yields, assist in planning irrigation schedules, apply fertilisers and provide valuable data on weather.

Despite the rapid pace of digitalisation, however, traditional herding and nomadic values prevail. During my stay with the herders in Khentii province, it slowly became clear that being online – and tuning into the modern, fast-paced world in general – was not their main priority.

“I would like to use the internet more because it’s fun and useful, but the animals like it here; this is a good place for them,” Batbayer says when I ask if better internet connectivity would be a decisive factor in his choice of where next to move his livestock.

“I would never choose Facebook over the well-being of the animals.”

Obvious, when you think about it – or at least it should be. In the Gobi Desert, another herder, named Khash-Erdene, explains how he balances the online and offline bits of his life. He’s part of a new wave of herders who don’t live permanently in a ger out in the countryside.

“Instead, he lives in a small village, Khanbogd, and has relatives and hired workers who look after the animals while he manages and monitors things via digital devices. He calls himself a “mobile herder”.

“I’m on the mobile or tablet with them, and they show me the animals and the surroundings on the screen,” he says. “It’s like I’m there with them. I can see the weather conditions, and I can tell them what to do and where to take the animals.

“I normally read the weather with my eyes, but I’m using different weather forecasting apps to double-check my observations. It’s quite efficient.”

The mobile herding set-up frees up time for him to take on other jobs to supplement the household income, such as working as a driver. This kind of work is plentiful thanks to Khanbogd’s proximity to the Oyu Tolgoi mining site.

He and his wife haven’t entirely abandoned the nomadic life, though: on weekends, they leave the village and head out to the countryside to stay in their ger. That’s his real life, he says.

Still, convincing his children to follow in his footsteps as a herder won’t be easy, he says, even as operations become more technologically enhanced and financially rewarding.

“Times change, generations change. They help me with the livestock, sure, but they want to go their own way.” Lowering his gaze, he adds: “The herder tradition in our family ends with me.”