Then & Now | Why Buddhist ritual of ‘saving lives’ is a death sentence for animals

The superstitious practice seen in Hong Kong and elsewhere of saving animals from imminent death only ensures the early demise of the innocent creatures

Buddhist notions of “saving life” can be observed in various rituals across Hong Kong. Contrary to popular belief, most of these customs are not Chinese in origin, but are a consequence of the spread of (originally Hindu) beliefs following the introduction of Buddhism into China, mainly via the overland Silk Road from Central Asia, around 200BC. Such traditions became prominent when, during the long period of international openness that characterised the Tang dynasty (618-907), modified versions of Buddhist cultural practices became integrated into mainstream Chinese life.

Maritime links with Southeast Asia, where assorted Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms held sway for more than 1,000 years, reinforced such practices.

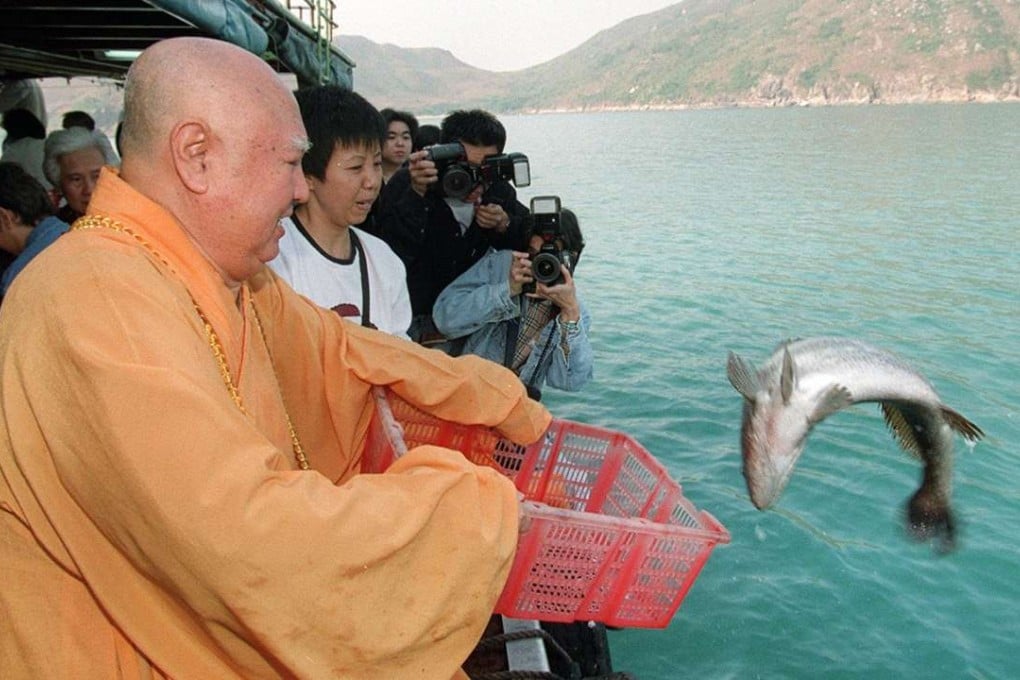

Because one of the principal tenets of Buddhism is to refrain from the taking of life, acting to rescue a creature otherwise ordained for death (usually to be slaughtered for food) is believed to bring merit. Saving fish or crabs in the market, for example, and releasing them into the wild, is a meritorious act believed to positively influence one’s own destiny. The mere fact of the animal’s release from captivity is deemed good enough; after the individual who released it has departed, that is the end of the matter as far as they are concerned.