Hong Kong’s shady past of antibiotic smuggling – the post-war penicillin racket

How black-marketeers made tidy fortunes by selling adulterated pharmaceuticals to China in the 1950s

From its grubby 19th-century beginnings, Hong Kong has been a natural home for rackets, scams and shoddy knock-offs. Unlovely business activities inevitably evolved in a place, and among people, on the world’s economic margins. One of the most profitable post-war schemes involved illicit penicillin.

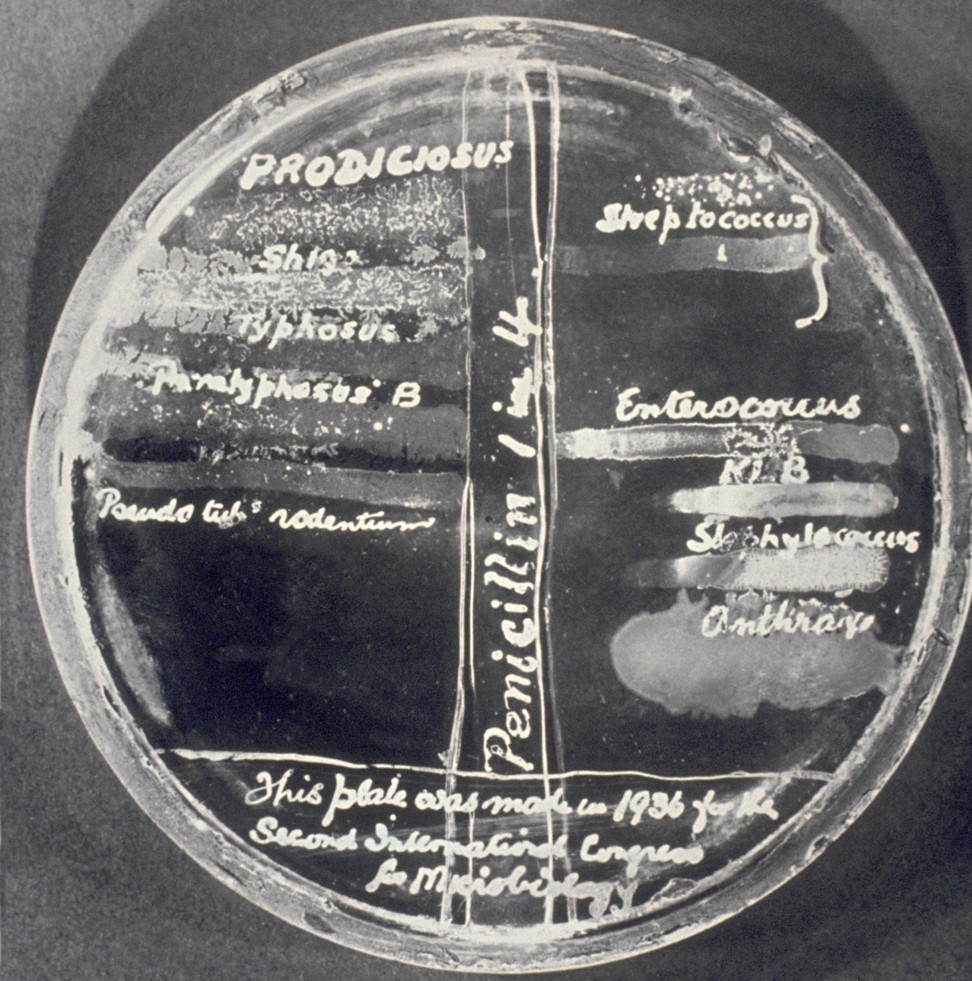

First identified in 1928 by Scottish scientist Alexander Fleming, and further developed by Australian pharmacologist Howard Florey and his team of researchers throughout the 1930s, penicillin’s antibiotic properties were one of the 20th century’s great discoveries. Penicillin’s medicinal use, accelerated by wartime demands after its successful introduction to human patients in 1942, transformed the world.

Why Hongkongers set such store by patent medicines and herbal tea

“Wonder drugs”, including penicillin, and other early antibiotics such as streptomycin, were life-saving treatments for septicaemia, tuberculosis, meningitis and other infections. Antibiotic-resistant disease strains, now a major threat to public health, were unknown, these drugs having been developed and introduced only a few years earlier.

Graham Greene’s screenplay The Third Man, set in Vienna in 1948, bases its dramatic plot around the post-war penicillin racket. In the film, the four occupying forces in the city (Britain, France, the United States and the Soviet Union) had excess supplies of the drug, owing to wartime overproduction.

Amoral black marketeer Harry Lime, superbly characterised by Orson Welles, had astutely spotted a commercial opening for the resale of black-market antibiotics to desperate patients. Active ingredients were adulterated – much like cocaine and heroin today – to further enhance already eye-watering profit margins and often rendering the black-market penicillin nearly useless.

In the late ’40s, as China imploded into civil war, a similar black market for penicillin evolved in Shanghai. Most drug supplies originated from the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), which operated from Shanghai in 1945-47. China was the largest single recipient of UNRRA aid.

Late Nationalist China’s extraordinary levels of corruption meant plentiful quantities of penicillin were misappropriated and profitably resold. Politically powerful individuals would look the other way for the right financial consideration.

Some Nationalist racketeers and their families later prospered in Hong Kong, their substantial fortunes based on selling adulterated penicillin in Shanghai, as their rotten regime crumbled and finally collapsed under the weight of its own venality.

When Hong Kong was haven for charlatans and fantasists

In the early 1950s, Hong Kong had various Harry Lime clones. Most were émigré Chinese, though a few European businessmen, bounced out of post-liberation China, also shared in the profits of this latter-day drug trade. “Patriotic” strategic commodity smuggling had been essential during the war, and the clandestine trading routes in and out of Japanese-occupied China proved just as effective a decade later.

The UN’s embargo on trade with Red China in 1950 halted the direct, legal import of key commodities, such as pharmaceuticals, which were not produced in sufficient quantities there at the time. This shortfall offered a ready opportunity to Hong Kong’s more “entrepreneurial” businessmen, who made quick profits surreptitiously reselling antibiotics in China.

International trade patterns helped facilitate the shady reselling of pharmaceuticals. Legally manufactured medicines could be legitimately imported into Hong Kong duty free, which made them cheaper than in their place of manufacture. Where they went afterwards was conveniently ignored by both manufacturers and their local distributors.

Most were legitimately re-exported to Southeast Asia, but many also found their way into China. Demand was especially high during the Korean war (1950-53), when China had significant troop commitments and penicillin and other life-saving pharmaceuticals were vital.