Then & Now | How American missionaries gave southern China its Swatow lace industry

Missionaries introduced embroidery to the Chiu Chow, helping a poverty-stricken region and endowing the diaspora with a distinct profession

Delicate, elaborately patterned Swatow embroidery and lace items continue to be popular purchases in Hong Kong, especially among Western tourists. This substantial cottage industry triangulated three distinct specificities: dialect group; adherence to a foreign religion – in this case, various Protestant sects; and the gravitational pull of an ancestral regional loyalty.

Swatow – now better known as Chiu Chow or Shantou – comprises several districts clustered around the border of Guangdong and Fujian provinces. Historically impoverished, Swatow was a net exporter of people for generations. Throughout the 19th century, Swatow emigrants – known as Teochew – sought a better life in Southeast Asia, settling in Penang, Singapore and beyond.

Clannish even by regional Chinese standards, Chiu Chow people banded closely together wherever they settled. The unofficial headquarters for the overseas Chiu Chow became, and remains, Bangkok; little publicised is the fact that the Thai royal family are directly descended from early Chiu Chow settlers.

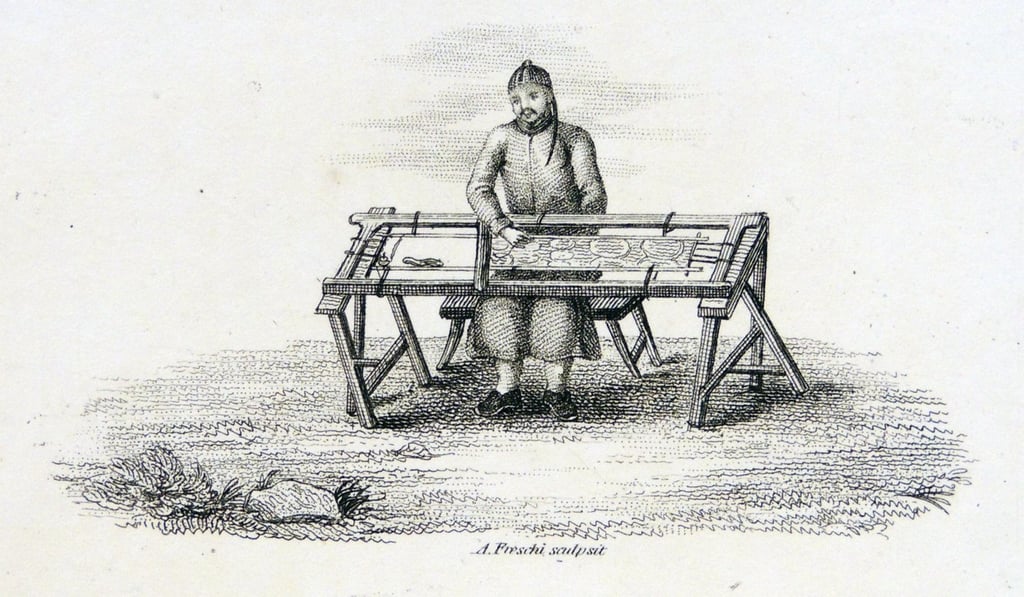

Swatow lace became renowned internationally from the late-19th century. Introduction of foreign lace-making and embroidery techniques was directly linked to the influence of Christian missionary activity in the Chiu Chow region, in particular that of American Presbyterian and Baptist sects. Two American missionaries, Sophia Norwood Lyall and Lida Scott Ashmore, are credited with bringing these skills to south China.

Later missionaries introduced Venetian and Belgian cross-stitch, drawnwork and cutwork techniques and fine cotton crochet patterns that, within a few decades, were providing a welcome source of income for impoverished communities.