Why ignore Naomi Osaka’s Haitian heritage? Identity has long been a product of mixed marriages, just look at China

In imperial China, the Han Chinese assimilated with rulers and subjects through intermarriage, a history that is largely ignored by labels that overlook the complexities of what came before

The beginning of the year saw tennis player Naomi Osaka triumph at the Australian Open and become the first Asian world No 1 in the women’s game.

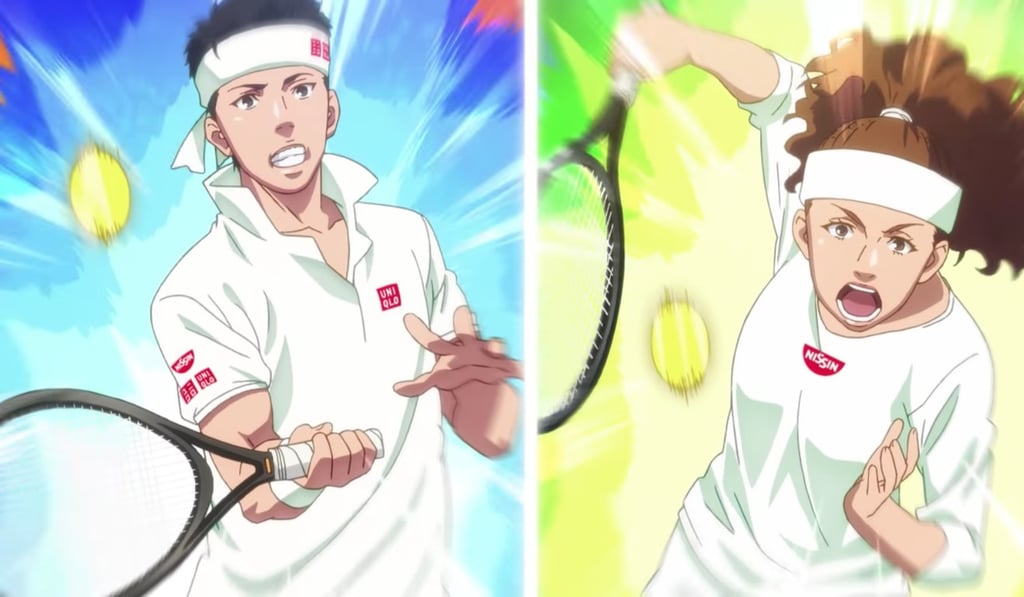

While Osaka, a child of a Haitian father and Japanese mother, is part-Asian, why is her Caribbean heritage ignored or even obscured, as Japanese food manufacturer Nissin recently tried to do in a heavily criticised marketing campaign? Why is golfer Tiger Woods not widely regarded as Asian when his mother is Thai?

I often wonder how people of mixed heritage decide who they are. Is it a personal choice, or one that is made for you by your family circumstances or by how you look? Is it a diktat from the state or the media? Do political or economic considerations come into play?

The Peranakans in Singapore did not have agency in making that decision. Descendants of early Chinese immigrants and local women in maritime Southeast Asia, Peranakans are neither Chinese nor Malay, but an amalgamation of both.

For various reasons, the British administrators of colonial Singapore and the post-independence government decided that the Peranakans were “Chinese”, ignoring the substantial non-Chinese ingredients that had gone into the melting pot.

However, most Chinese today are products of miscegenation. The Huaxia people, precursors of the Han Chinese, were believed to have radiated outwards from the Yellow River valley, intermarrying with and absorbing the other “barbarians” living in the valley’s periphery.