Then & Now | Fireworks banned in Hong Kong? The rules, apparently, don’t apply to the New Territories

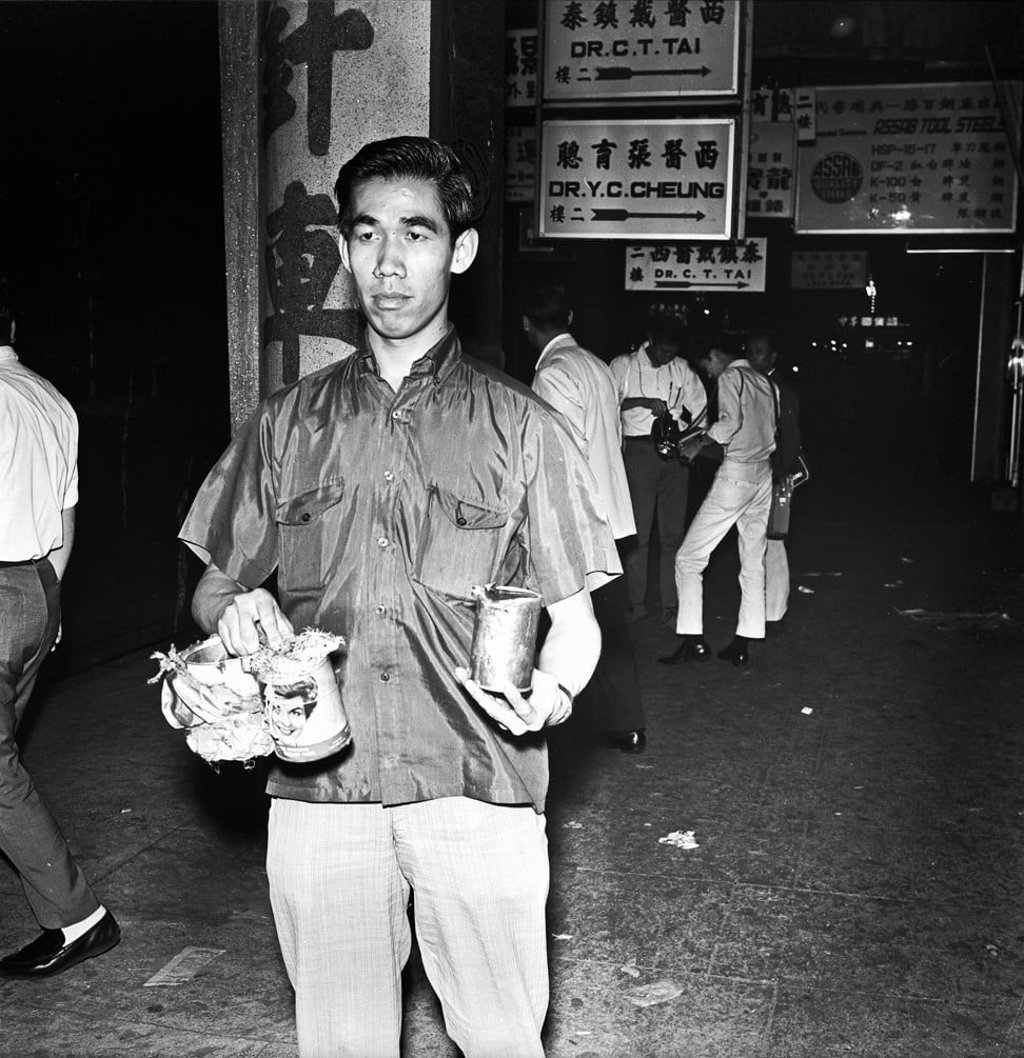

A complete ban on fireworks was lifted in 1975 to allow government-organised displays but, in complete disregard of the law, colourful firecrackers have been lighting up the New Territories skies every Lunar New Year, as authorities look the other way

In all their ear-splitting variations, fireworks have sharply punctuated Chinese life for more than a millennia. At every festival or significant life event, from weddings and the birth of sons to funerals, fireworks have been deployed. Cracking explosions, colourful sky-bursts and choking clouds of peacefully discharged smoke are one of the few happy uses to which gunpowder – a Chinese invention – has been put. Every Lunar New Year, Hong Kong’s most keenly anticipated seasonal festivity witnesses the detonation of several million dollars’ worth of fireworks over Victoria Harbour.

Around my home in Shek Kong, the constant din of firecrackers, and periodic burst of skyrockets, intersperse the festival period. The nocturnal explosions serve as an annual reminder that “rule of law” in Hong Kong is – and always has been – only intermittently applied, especially to the powerful and well-connected in rural areas, whatever those with a vested interest in proclaiming otherwise might say.

More than 30 years ago, my first Lunar New Year in the New Territories – in Kam Tin – was spent amid the din from thunderflashes, Roman candles, Catherine wheels, skyrockets that discharge eight flares apiece, and thousands of metres of firecracker strings of various percussive strengths. All could be inexpensively bought in the local market, with a quiet word to the right person. For three nights in a row, the blasts and booms felt and smelled like a faint echo of what I imagine the first world war might have been like; around 3am on the third night, I vividly recall sitting up in bed and noticing that the sound had died away. For the first time in days, no detonation could be heard anywhere. All Quiet on the New Territories Front …

City-dwelling friends disbelieved me when – some days later – I recounted the cacophony. “Firecrackers have been banned in Hong Kong since the 1967 riots,” one senior figure pontificated. “They are quite unavailable. And if by chance any were set off, the police would be round within minutes.”